Why Did the South Lose the Civil War?

Editor’s note: This story from 1988 contains dated language that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

For nearly half a century after Appomattox, the most popular explanation in the South for Confederate defeat was the one advanced by Robert E. Lee himself in his farewell address to his soldiers: “The Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.” This interpretation enabled southerners to preserve their pride in the courage and skill of Confederate soldiers, to reconcile defeat with their sense of honor, and even to maintain faith in the righteousness of their cause. The South, in other words, had lost the war not because it fought badly, or because its soldiers lacked courage, or because its cause was wrong, but simply because the enemy had more men and guns.

Many Yankees accepted this “overwhelming-numbers-and-resources” argument. While northerners believed that they had won because they had fought for a better cause, many of them were also ready to its War of Independence against mighty Britain. In this year of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, we are familiar with the truth that victory does not always ride with the heaviest battalions.

In the Civil War, the South waged a strategically defensive war to prevent its territory from being conquered and to preserve its armies from annihilation. To “win” the war, the Confederacy did not have to conquer the North; it needed only to hold out long enough to force the other side to the conclusion that the price of conquering the South and annihilating its armies was too high, as Britain had concluded in 1781 and as the United States concluded with respect to Vietnam in 1972. Most southerners thought in 1861 that their resources were sufficient to win on these terms.

Even after losing the war, many southerners continued to insist that this reasoning remained sound. In his memoirs, General Joseph E. Johnston maintained that the southern people had not been “guilty of the high crime of undertaking a war without the means of waging it successfully.” To be sure, Johnston had an axe to grind: he blamed the Confederate defeat on the inept leadership of Jefferson Davis.

This overwhelming-numbers-and-resources argument has thus lost favor among most historians. The distinguished historians who co-authored Why the South Lost the Civil War (1986) have written that “an invader needs more force than the North possessed to conquer such a large country as the South, even one so limited in logistical resources.” This goes a bit too far; if read literally, it seems to say that the North could not have won the war. Perhaps a better way to put it is this: to win the kind of total war that the Civil War had become by 1863, the North had to conquer vast stretches of southern territory, cripple the South’s resources, and destroy the fighting power of Confederate armies; therefore, northern superiority in manpower and resources was necessary to Union victory, but it alone does not explain it.

When the numbers-and-resources theory lost popularity, it was replaced, especially among southern-born historians, with what might be termed an “internal conflict” theory: the South lost because it was plagued by dissent and divisions that undercut the strong and united effort necessary to win the war. Exponents of this interpretation have emphasized various kinds of internal conflict.

The first and one of the most durable themes, as spelled out by Frank Owsley in his State Rights in the Confederacy (1925), was that the centrifugal force of state rights fatally handicapped the efforts of the central government and the army to mobilize men and resources for the war. Owsley especially singled out Governors Joseph Brown of Georgia and Zebulon Vance of North Carolina and condemned their obstructive policies, their withholding of men and arms from the Confederate army for their state militias, and their political guerrilla warfare against Jefferson Davis’s administration. Owsley declared that on the tombstone of the Confederacy should be carved the epitaph, “Died of State Rights.”

A variant of the state-rights thesis focuses on the resistance of many southerners to such war measures as conscription, certain taxes, suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, and martial law. Opponents based their denunciations of these “despotic” measures on grounds of civil liberty, state rights, democratic individualism, or all three. According to this interpretation, these opponents crippled the army’s ability to fill its ranks, obtain food and supplies, and stem desertions, and they hindered the government’s capacity to crack down on antiwar activists. The persistence during the war of the democratic practices of individualism, dissent, and carping criticism of the government caused historian David Donald, writing in 1960, to amend the inscription on the Confederacy’s tombstone to “Died of Democracy.”

There are three problems with this internal-conflict thesis as an explanation for Confederate defeat. First, recent scholarship has demonstrated that the negative effects of state-rights sentiment on the southern war effort has been much exaggerated. State leaders like Brown and Vance did indeed feud with the David Administration and criticize the president’s leadership. But at the same time, these and other governors took the initiative in many areas of was mobilization — raising regiments, equipping them with arms and uniforms, providing help for their families at home, organizing war production, supply, and transportation, building coastal defenses, and so on. It now seems quite clear that rather than hindering the efforts of the government at Richmond, the activities of states augmented them.

As for the “Died of Democracy” thesis, a good case can be made that, to the contrary, the South enforced the draft, suppressed dissent, and suspended civil liberties and democratic rights more thoroughly than the North did. The Confederacy enacted conscription a year before the Union, and raised a considerably larger portion of its troops by drafting than did the North. And although Lincoln possessed more authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and used this power more often to arrest antiwar activists than did David, the Confederate military suppressed unionists with greater ruthlessness — especially in east Tennessee and western North Carolina — than Union forces wielded against Copperheads in the North or Confederate sympathizers in the border states.

This points to the second major problem with the internal conflict interpretation, which we might call the fallacy of reversibility. That is, if the North had lost the war — which came close to happening on more than one occasion — the same thesis of internal conflict could be used to explain northern defeat. Bitter divisions and dissent existed in the North over conscription, taxes, suspension of habeas corpus, martial law — and significantly in the case of the North, over emancipation of the slaves as a war aim. If anything, the opposition was more powerful and effective in the North than in the South. Lincoln endured greater vilification than Davis during much of the war. And he had to face a campaign for reelection in the midst of the most crucial military operations of the war — an election that for a time it appeared he would lose. This did not happen, but its narrow avoidance is evidence of intense conflict within the northern polity, a reality that tended to neutralize the similar but probably less divisive conflicts in the South as a cause of Confederate defeat.

Finally, one might ask whether these internal conflicts over the correct means of waging the war were greater in the Confederacy than they had been in the United States during the Revolution. Americans in the war of 1776 were more divided than southerners in the war of 1861, yet the United States won its independence and the Confederacy did not. Apparently we must look elsewhere for an explanation of Confederate failure.

Similar criticisms apply to another interpretation that overlaps the internal-conflict thesis, what might be termed the “internal alienation” argument. Two large groups in the Confederacy were or became alienated from the war effort: nonslaveholding whites and slaves. The nonslaveholders constituted two-thirds of the southern white population. Many of them, especially in mountainous and hill-country regions of small farms and few slaves, opposed secession in 1861. They formed significant enclaves of unionism in western Virginia, where they created a new Union state, and in east Tennessee, where they carried out guerrilla operations against the Confederacy and contributed many soldiers to the Union army. Other yeoman farmers who supported the Confederacy at the outset, and fought for it, became alienated over time because of disastrous inflation, food shortages, high taxes, and a growing conviction that they were risking their lives and property to defend slavery. The conscription law, which allowed the well-off to pay for substitutes and wholly exempted one white man on every plantation with twenty or more slaves, lent force to the bitter cry that it was a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight. As food shortages and inflation worsened, many soldiers deserted from the army to return home and support their families. Several historians have argued that this seriously weakened the Confederate war effort and brought eventual defeat.

The alienation of many southern whites was matched by the alienation of a large portion of that two-fifths of the southern population that was black and enslaved. Slaves were essential to the Confederate war effort. As the majority of the labor force, they made it possible for the South to muster three-quarters of its white men of military age into the armed forces — compared with about half in the North. But most slaves who reflected on their stake in the war believed that a northern victory would bring freedom, and tens of thousands voted with their feet bye scaping to Yankee lines, where the North converted their labor and, eventually, their military manpower into a Union asset. This leakage of labor from the Confederacy and the unrest of slaves who remained behind retarded southern economic efficiency and output. It also drained manpower from the Confederate army by keeping some white men at home to control the increasingly restless slave population.

The alienation of these two large blocs of the southern people seems therefore a plausible explanation for Confederate defeat. But some caveats are in order. The alienated elements of the American population during the Revolution were at least as large as in the South during the Civil War. In the Revolution, many slaves ran away to the British, while the Loyalist whites undoubtedly weakened the American cause more than the disaffected nonslaveholders weakened the Confederate cause. Yet the American colonists triumphed and the Confederates did not. It is easy to exaggerate the degree of class conflict among whites in the South; it seems likely that some historians have done just that. And it’s important to note that the slaves who escaped to Union lines could only do so where northern forces controlled Confederate territory.

But perhaps the most important weakness of the internal-alienation thesis is that same fallacy of reversibility I have already mentioned. Large blocs of northerners were bitterly, aggressively alienated from the Lincoln Administration’s war policies. Their opposition weakened and at times threatened to paralyze the Union war effort. Perhaps one-third of the border-state whites actively supported the Confederacy, and many of the remainder were at best lukewarm unionists, especially after emancipation became a Republican war aim. Guerrilla warfare behind Unions lines occurred on a far larger scale than behind Confederate lines.

In the free states, the Democratic Party made conscription, emancipation, certain war taxes, the suspension of habeas corpus, and other wartime measures the basis for a relentless attempt to cripple the Lincoln Administration. The peace wing of the party, the Copperheads, opposed the war itself as a means of restoring the Unions. If the South had its class conflict over the theme of a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight (or its perception as such), so did the North. If the Confederacy had its bread riots, the Union had its draft riots, which were much larger and more violent. If many soldiers deserted from southern armies, an equally large percentage deserted from northern armies until the fall of 1864, when the southern rate increased because of a perception that the war was lost. Desertion here was primarily a result of defeat, not a cause. If the South had its slaves who wanted Yankee victory and freedom, the North had its Democrats and border-state unionists who bitterly opposed emancipation and withheld their support from the war because of it. The similar and probably greater alienation within the North thus neutralizes this theory.

Another category of explanations for southern defeat might be described as the “lack of will” thesis. It hold that the Confederacy could have won if the southern people had possessed the will to make the sacrifices necessary to achieve victory. The South lost the war, said E. Merton Coulter (a southerner) in The Confederate States of America (1950), because its “people did not will hard enough and long enough to win.”

Three principal themes have emerged in this lack-of-will thesis. First is the argument that the Confederacy lacked a strong sense of nationalism. The Confederate States of America, in this interpretation, did not exist long enough to give its people that mystical faith we call nationalism, or patriotism. Southerners did not have as firm a conviction of fighting for a country or a deep-rooted political and cultural tradition as northerners did. Southerners had been Americans before they became Confederates, and many of them had opposed secession. So when the going got tough, their residual Americanism reemerged and triumphed over their newly minted Confederate nationalism. To clinch the argument, proponents of the lack-of-will thesis point to the Confederate Constitution, which in most respect was a verbatim copy of the United States Constitution; the Confederate national flag, which was similar to the American flag; and the Confederate currency, which bore portraits of Washington, Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, and other American heroes.

But this argument misses the point. Confederates regarded themselves as the true heirs of American nationalism. The South, said Jefferson Davis in his first message to the Confederate Congress after Fort Sumter, was fighting for the same “sacred right of self-government” that its forefathers of 1776 had fought for. When the Yankees repudiated the ideals of their revolutionary fathers, southerners seceded to form a government that would conserve the genuine American heritage.

The notion that Confederate nationalism was not as heartfelt as the American nationalism of northerners is contradicted by the wartime letters and diaries of soldiers and civilians. If anything, southerners expressed a fiercer patriotism and a greater determination to die in the last ditch than northerners did. As the Confederate War Department clerk John Jones wrote in his diary in 1863, “Our men must prevail in combat, or lose…everything.” Evidence that southerners persisted through far greater hardships and suffering than northerners experienced could be piled up endlessly. Northerners almost threw in the towel in the summer of 1864 because of casualty rates that southerners had endured for more than two years. Only the military victories at Atlanta and in the Shenandoah Valley pulled the North out of its doldrums, while the South continued to fight on for eight months more without any victories to reinforce its nationalism. In the light of all this, it seems difficult to accept weak nationalism as the cause of Confederate defeat.

A second theme in the lack-of-will interpretation is what might be termed the “guilt thesis” — the suggestion that many southern whites felt moral qualms about slavery that undermined their will to win a war to preserve slavery. The South suffered from “a weakness of morale,” wrote historian Kenneth Stampp, because of “widespread doubts” about the “validity of the Confederate cause.” Defeat rewarded these guilt-ridden southerners with “a way to rid themselves of the moral burden of slavery,” so a good many of them, “perhaps subconsciously, welcomed…defeat.” Other historians with a bent for social science concepts have agreed that Confederate morale suffered from the “cognitive dissonance” of fighting a war to establish their own liberty but keep four million black people in slavery.

Historians who want to believe that southern whites felt guilty about slavery find this thesis attractive, but little evidence for it exists outside their imaginations. To be sure, one can find quotations from southerners that express doubts about slavery, and one can find statements by southerners after the war that express relief that it was gone. But the latter are somewhat suspect in their sincerity, and in any case, one can find far more quotations on the other side — assertions that slavery was a positive good, the best labor system, and the best system of social relations between a superior and inferior race.

In any event, most Confederates did not consider themselves to be fighting primarily for slavery but for independence, and by 1865, most of them were prepared to give up slavery if that was the price of independence. If slavery weakened southern morale to the point of causing defeat, it should have weakened American morale during the Revolution even more, for Americans of that generation felt considerably more doubt and guilt about slavery than did southerners in 1861. And it is hard to see that Robert E. Lee, who did not believe in slavery or secession, made a lesser contribution to Confederate victory than, say, Braxton Bragg, who believed firmly in both.

A third theme in the lack-of-will interpretation focuses on religion. Southerners were a religious people; under the stress of suffering and death during the war, they became more religious. Southern clergymen preached at the outset of the war that God was on their side. Leonidas Polk, an Episcopal bishop who also was a West Point graduate and became a lieutenant general in the Confederate army, said in 1861 that “We of the Confederate States are the last bulwarks of civil and religious liberty; we fight for our hearthstones and our altars; above all, we fight for a race that has been by Divine Providence committed to our most sacred keeping.” No qualms of guilt about slavery here; no lack of will or nationalism; no doubts about which side God favored.

But as the war went on, and as the South suffered so much death and destruction, some southerners began to doubt whether God was on their side after all. Perhaps, on the contrary, he was punishing them for their sins. Several historians have pointed to this religious conviction as a source of defeatism and loss of will that corroded Confederate morale and contributed to southern defeat.

Note that I said “loss of will” — not lack. A people at war whose armies are overwhelmed, whose economy is wrecked, and whose country is occupied quite naturally lose their will to continue the fight because they have lost the means to do so. That is what happened to the South. If one analyzes carefully the lack-of-will thesis, it becomes clear that what its proponents are really describing is a loss of the will to carry on, not an initial lack of will. This analysis places the cause-effect relationship in the right order — military defeat caused loss of will, not vice versa. It introduces external agency as a crucial explanatory factor — the agency of northern military success, especially in the eight months after August 1864. The main defect of the lack-of-will thesis, as well as the internal-conflict and internal-alienation interpretations, is that all of them attribute southern defeat to factors intrinsic to the Confederacy. They tend to ignore the existence of an outside force battering away at the South.

This reminds one of the controversies that have swirled endlessly in the South for the past 125 years over who was responsible for the loss at Gettysburg. Commentators have blamed almost every prominent Confederate general at Gettysburg for mistakes that lost the battle: Lee himself for mismanagement, overconfidence, and poor judgment; Stuart for riding off on a raid and leaving Lee blind in the enemy’s country; Ewell and Early for failing to attack Cemetery Hill on the afternoon of July 1st and for tardiness in attacking on July 2nd; and most frequently, Longstreet for lack of cooperation, speed, and vigor in the assaults of July 2nd and 3rd. It was left to George Pickett to put his finger on the problem with all these explanations. When someone asked him after the war who was responsible for the defeat at Gettysburg, he thought for a moment and replied: “I’ve always thought the Yankees had something to do with it.”

The overwhelming-numbers-and-resources argument at least has the merit of attributing the Confederate defeat in part to the Yankees. But as noted earlier, that thesis has serious deficiencies. Another category of interpretations with an external dimension, however, has enjoyed greater popularity and durability — the issue of leadership. Numerous historians, but northern and southern, have argued that the North developed superior leadership — on three different levels — and this became the main factor in the ultimate Union victory.

First, generalship. A fairly broad consensus exists that the South benefited from better generalship in the first half of the war, especially at the tactical level and in the eastern theater. But by 1863 and 1864, a small group of northern generals, including Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan, had emerged to top command with a firm grasp of the need for coordinated offensives in all theaters, a concept of the total-war strategy necessary to win the conflict, the skill to carry out this strategy, and the relentless, ruthless determination to keep fighting — despite high casualties — until the South surrendered unconditionally. In this interpretation, the Confederacy had brilliant tactical leaders, such as Lee, Jackson, Forrest, and others, who also showed strategic talent in limited theaters. But the South had no generals who rose to the level of overall strategic genius that Grant and Sherman demonstrated. Lee’s strategic vision was limited to the Virginia theater, where his influence concentrated Confederate resources at the expense of the western theaters. In the West, the Confederacy suffered from poor generalship, and here it really lost the war.

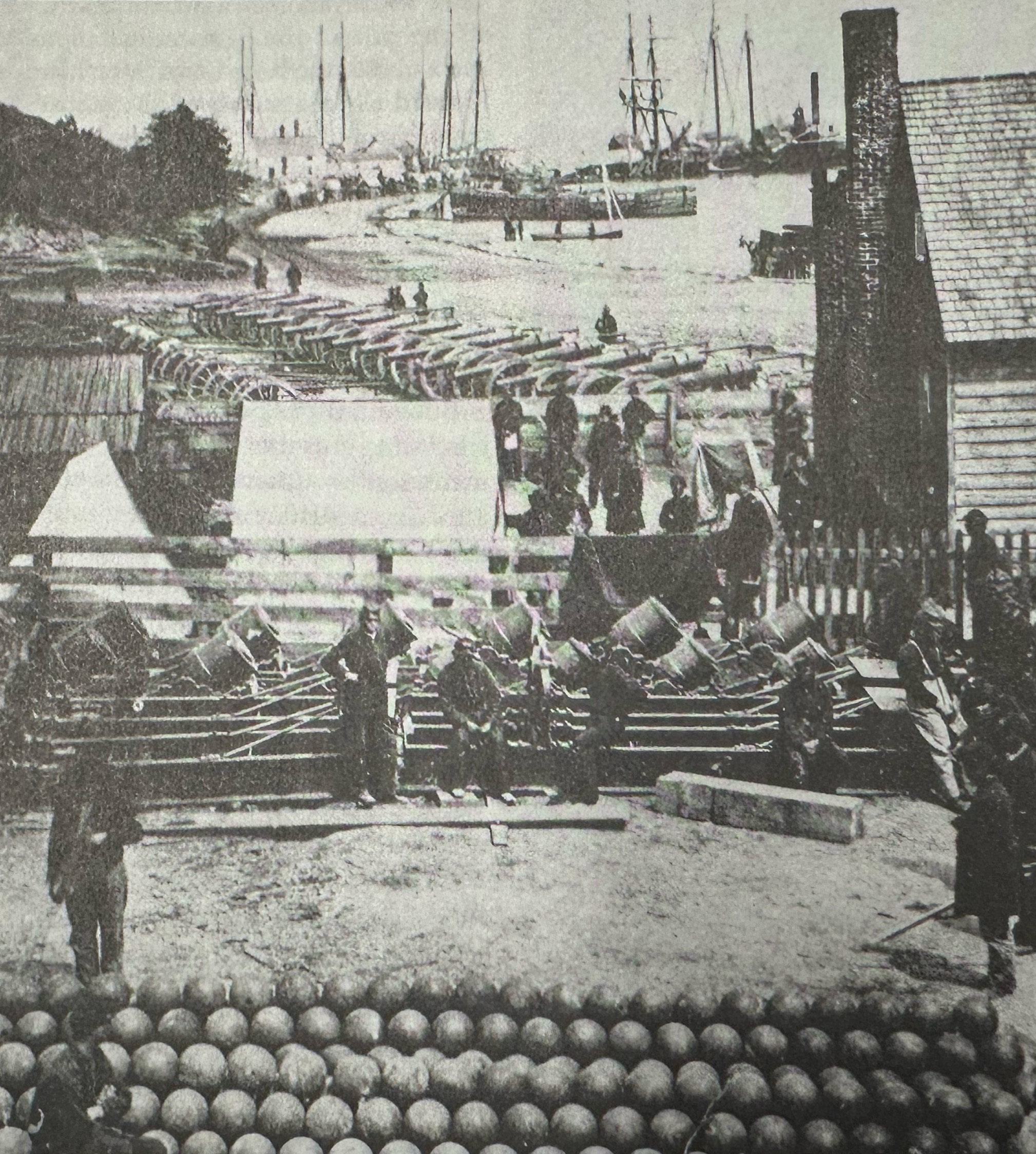

The second level at which a number of historians have identified superior northern leadership is in the management of military supply and logistics. In Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Quartermaster-General Montgomery Meigs, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox, and Daniel McCallum and Herman Haupt (administrators of military railroads), among other officials, the North developed by 1862 a group of top- and middle-level managers who organized its economy and the logistical flow of supplies and transportation to its armies with unprecedented efficiency and abundance. The Confederacy could not match northern skill in organization and administration. Nor did the South manage its economy as well as the North. While the Union developed a balanced system of taxation, loans, and treasury notes to finance the war without unreasonable inflation, the Confederacy relied mostly on fiat money, and it suffered a crippling 9,000 percent rate on inflation by war’s end. In this interpretation, it was not the North’s greater resources but its better management of those resources that won the war.

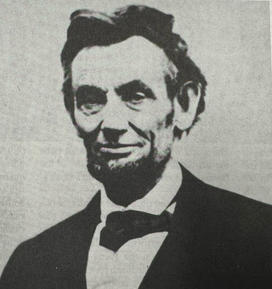

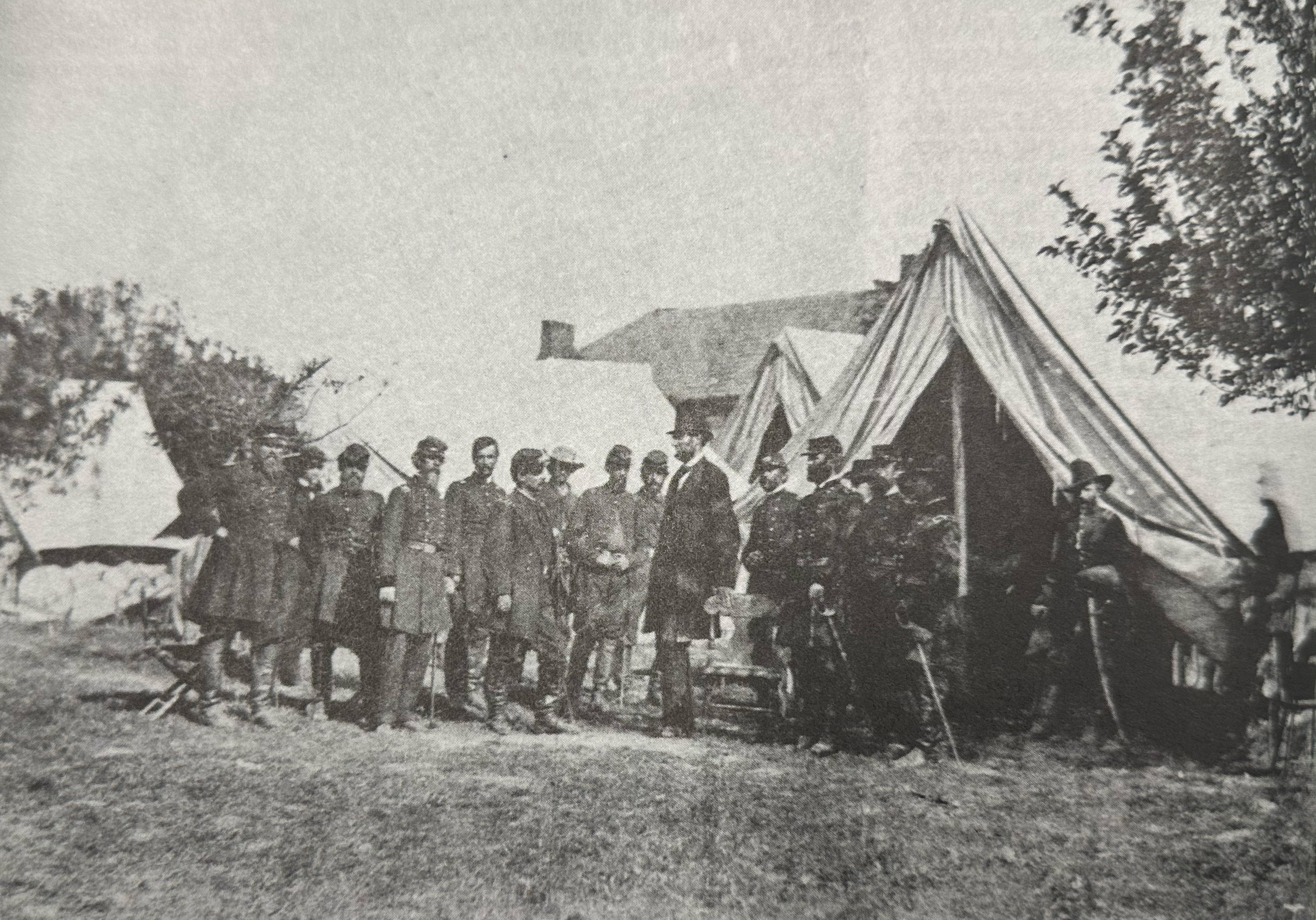

Third, leadership at the top. Lincoln proved to be a better commander-in-chief than Davis. On this issue, there has been almost complete unanimity among historians of northern birth and surprising agreement by many southerners. In 1960, for example, the southern-born historian David Potter wrote, “If the Union and Confederacy had exchanged presidents with one another, the Confederacy might have won its independence.”

This may be carrying a good point too far. In any event, a broad consensus exists that Lincoln was more eloquent than Davis in expressing war aims, more successful in communicating with the people, more skillful as a political leader in keeping factions working together for the war effort, and better able to endure criticism and work with his critics to achieve a common goal. Lincoln was flexible and pragmatic, with a sense of humor to smooth relationships and help him survive the stress of his job; Davis was austere, rigid, and humorless, with the type of personality that readily made enemies. Lincoln had a strong physical constitution; Davis was frequently prostrated by sickness. Lincoln picked good administrative subordinates and knew how to delegate authority to them; Davis went through five secretaries of war in four years, and he spent a great deal of time and energy on petty details that he should have left to subordinates. A disputatious man, Davis sometimes seemed to prefer winning an argument to winning the war; Lincoln was happy to lose an argument if it would help win the war. Davis’s well-known feuds with two of the South’s premier generals, Pierre G. T. Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston, undoubtedly hurt the South’s war effort.

The thesis of superior northern leadership seems more convincing than other explanations of Union victory. But it should not be accepted uncritically. With respect to generalship, for example, comparisons of Grant and Lee, Sheridan and Forrest, Sherman and Johnston, and so on, are a minefield through which historians must tread carefully. And even if the North did enjoy an advantage in this respect during the last year or two of the war, the Union army had its fainthearts and blunderers, its McClellans and Popes who nearly lost the war to superior Confederate leadership in the East in 1862 and 1863 despite what was happening in the West. On more than one occasion, the outcome seemed to hang in the balance because of incompetent northern military leadership.

As for Union superiority in the organization and management of logistics and supply, this was probably true in most respects. Northern society was more entrepreneurial and business-oriented than southern society; the Union war effort could draw on a much wider field of talent to mobilize men, resources, industry, and transportation. Yet the South could boast some brilliant successes in this area of leadership. Ordnance Chief Josiah Gorgas built from scratch an arms and ammunition industry that kept Confederate armies better supplied than had seemed possible at the outset of the war. The brothers George and Gabriel Rains accomplished miracles in the establishment of nitrate works, the manufacture of gunpowder, and the invention of explosive mines (then called torpedoes), which turned out to be the Confederacy’s most potent naval weapon. What seems most significant about Confederate logistics and supply is not their obvious deficiencies, but the ability of southern officials to do so much with so little. Instead of losing the war, it could be argued that their efforts did much to keep the Confederacy fighting for so long.

Finally, what about Lincoln’s superiority to Davis as commander-in-chief? This seems indisputable, and as an admirer of Lincoln, I would be one of the last to dispute it. Yet Lincoln made some mistakes as a war leader. He went through a half-dozen failures as commanders in the eastern theater before he found the right general. But in the summer of 1864, when the war seemed to be going badly for the North and Lincoln came under enormous pressure to negotiate peace with the Confederacy — tantamount to admitting northern defeat — he resisted this pressure. His decision appeared to cost him his reelection. If the election had been held in August 1864 instead of November, Lincoln would have lost. He would thus have gone down in history as an also-ran, a loser unequal to the challenge of the greatest crisis in the American experience. And Jefferson Davis might have gone down in history as the George Washington of the southern Confederacy.

That these hypothetical events did not happen was due to events on the battlefield — principally Sherman’s capture of Atlanta and Sheridan’s three spectacular victories over Early in the Shenandoah Valley. These events turned northern opinion from deepest despair in the summer to confident determination by November. In July, Horace Greeley wrote to Lincoln, pleading with him to open peace negotiations with the Confederacy. “Our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country,” said Greeley, “longs for peace.” But, three months later, a British war correspondent expressed astonishment at the “extent and depth” of northern “determination to fight to the last.”

This transformation illustrates the point made earlier that the will of either the northern or southern people was more the result of military victory than a cause of it. Events on the battlefield might have gone the other way, and if they had done so, the course of the war might have been quite different. It is this element of contingency that is missing from generalizations about the cause of Confederate defeat, whether such generalizations focus on external or internal factors. There was nothing inevitable about northern victory in the Civil War. There were several major turning points, points of contingency when events moved in one direction but could well have moved in another. Two moments of contingency earlier in the conflict, before the decisive events of the fall of 1864, equaled this final turning point in importance.

The first of them occurred in the fall of 1862. Confederate offensives during the summer had taken southern armies from Mississippi almost to the Ohio River and from the gates of Richmond to across the Potomac River by September. But in September and October, Union armies drove back these southern invaders at Antietam and Perryville. These repulses forestalled European intervention, convinced northern voters not to repudiate the Lincoln Administration in the Congressional elections by voting for Democrats, and emboldened Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which enlarged the scope and purpose of the war.

The other major turning point occurred in the summer and fall of 1863. During the months between the Union defeats at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, a time that also witnessed Union failures in the western theater, northern morale dropped to its lowest point except, perhaps, during the late summer of 1864. The usually indomitable Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., recovering from the second of the three wounds he received during the war, wrote that “the army is tired” and concluded that “the South have achieved their independence.” But then came the Battle of Gettysburg and the surrender of Vicksburg in July and (after a southern triumph at Chickamauga) the calamitous Confederate defeat at Chattanooga in November. This crucial turning point produced southern cries of despair. At the end of July, Confederate Ordnance Chief Gorgas wrote, “Yesterday we rode on the pinnacle of success — today absolute ruin seems to be our portion. The Confederacy totters to its destruction.”

Predictions in late 1863 of the Confederacy’s imminent collapse turned out to be premature. More twists and turns marked the road to the end of the war. But this fact only underscored the importance of contingency. To understand why the South lost in the end, we must turn from large generalizations that imply inevitability and study instead the contingency that hung over each military campaign, each battle, each election, each decision during the war. When we comprehend what happened in these events, how it happened, why it happened, and what its consequences were, then we will be on our way toward answering the question, Why Did the South Lose the Civil War?

--

James M. McPherson, the Edwards professor of American history, is the author of Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford University Press), a history of the Civil War that the New York Times named one of the best books of 1988. This essay is adapted from a lecture he presented to returning alumni on the morning of the Harvard football game this fall.

This was originally published in the December 7, 1988 issue of PAW.

No responses yet