The Wonderful Life of Jimmy Stewart ’32

A museum in Indiana, Pennsylvania, celebrates its famous son and Princeton’s most beloved alumnus

D. W. Miller ’89, a former staff write for PAW, is the managing editor of Policy Review magazine, in Washington D.C. For more on the Jimmy Stewart Museum, write P.O. Box One, Indiana, PA 15701 (1-800-83-JIMMY), or visit its Website (http://www.jimmy.org). For more on Jimmy Stewart, readers can turn to James Stewart: A Biography, by Donald Dewey, published this year by Turner Publishing, Inc., of Atlanta, Georgia.

“What’d you wish, George?”

“Oh, not just one wish, a whole hatful. Mary, I know what I’m going to do tomorrow, and the next day, and next year, and the year after that. I’m shakin’ the dust of this crummy little town off my feet and I’m gonna see the world! Italy, Greece, the Parthenon, the Colosseum. Then I’m comin’ back here and go to college and see what they known and then I’m gonna build things.

I’m gonna build airfields, I’m gonna build skyscrapers a hundred stories high, I’m gonna build bridges a mile long….”

Movie buffs surely recognize this ebullient speech as the doomed vision of George Bailey, the fictitious hero of It’s a Wonderful Life. That film, which celebrates tis 50th anniversary this month, is often regarded as a corny tribute to small-town stalwarts who embody the best features of the American character: thrift, selflessness, loyalty, honesty, patriotism. Watching this movie has become a Christmas ritual for millions.

In reality, the film’s plot is driven by the darker side of the small-town mythos. Bad luck and the humdrum obligations to his family and his community of Bedford Falls conspire to frustrate George Bailey’s ambitions. Bitter and desperate, he is driven to thoughts of suicide. But a guardian angel named Clarence shows him the true nature of “success” by revealing the fate of his community had he never been born. As the film suggests, American culture is ambivalent about its small-town roots. Small towns are supposed to be bastions of clean and moral living, and yet they are the very places from which talented, ambitious people ought to escape.

One town in western Pennsylvania somehow manages to embrace both of these notions at once. Indeed, Indiana, Pennsylvania, may be the only place in America with the nerve to fashion itself a latter-day Bedford Falls. The self-proclaimed Christmas tree capital of the world (a million shipped annually), Indiana holds a festival each December celebrating It’s a Wonderful Life. Although many towns can boast the physical charm of Bedford Falls, only Indiana can claim the legacy of actor Jimmy Stewart ’32, the celluloid embodiment of small-town values and the star of the film.

For years, the town had noted is connection to Stewart with a modest plaque at his birthplace at 965 Philadelphia Street. But recently the town has sought to canonize its famous native. In 1983, it staged a grand celebration of his 75th birthday; thousands thronged a parade along Philadelphia Street that climaxed with the unveiling of a large bronze statue of him in front of the county courthouse. Seventh Street, which leads to his boyhood home atop nearby Vinegar

Hill, was renamed Jimmy Stewart Boulevard. And in May of last year, Indiana’s affection for Stewart culminated in the opening of a small museum to honor his life.

As it happens, Stewart’s glittering biography is practically the reverse of George Bailey’s. He left home as a teenager, earned a Princeton degree in architecture, and then eschewed bridge- building for a long and acclaimed career as a Hollywood actor. Indiana residents like to say that Stewart’s life reflects the virtues of the community where he grew up. That claim, and the museum that enshrines it, pose some interesting questions: Can a life lived far removed from its roots still exalt those roots? Can a man famous for simulating integrity and decency on screen embody them in real life?

“Some folks just wanted to focus on the entertainment aspect of his life,” says Ellen von Karajan, the museum’s executive director, “but we want to be an instrument for reminding people of those values that he learned growing up here.” The museum offers visitors dozens of Stewart artifacts from his life and career, a history of Indiana, a genuine Oscar statuette, and a 52-seat movie theater for regular screenings of Stewart’s films. It is a tribute to Stewart that seems to reflect perfectly—in scale and location, in atmosphere and content—not just a glamorous career that spanned six decades and 80 films, but the totality of his life. The accounts of his childhood, his service as a bomber pilot in World War II, and the integrity evident in his personal life suggest that, in this instance at least, small-town virtue was neither a casualty of ambition nor a mere inspiration for Hollywood artifice.

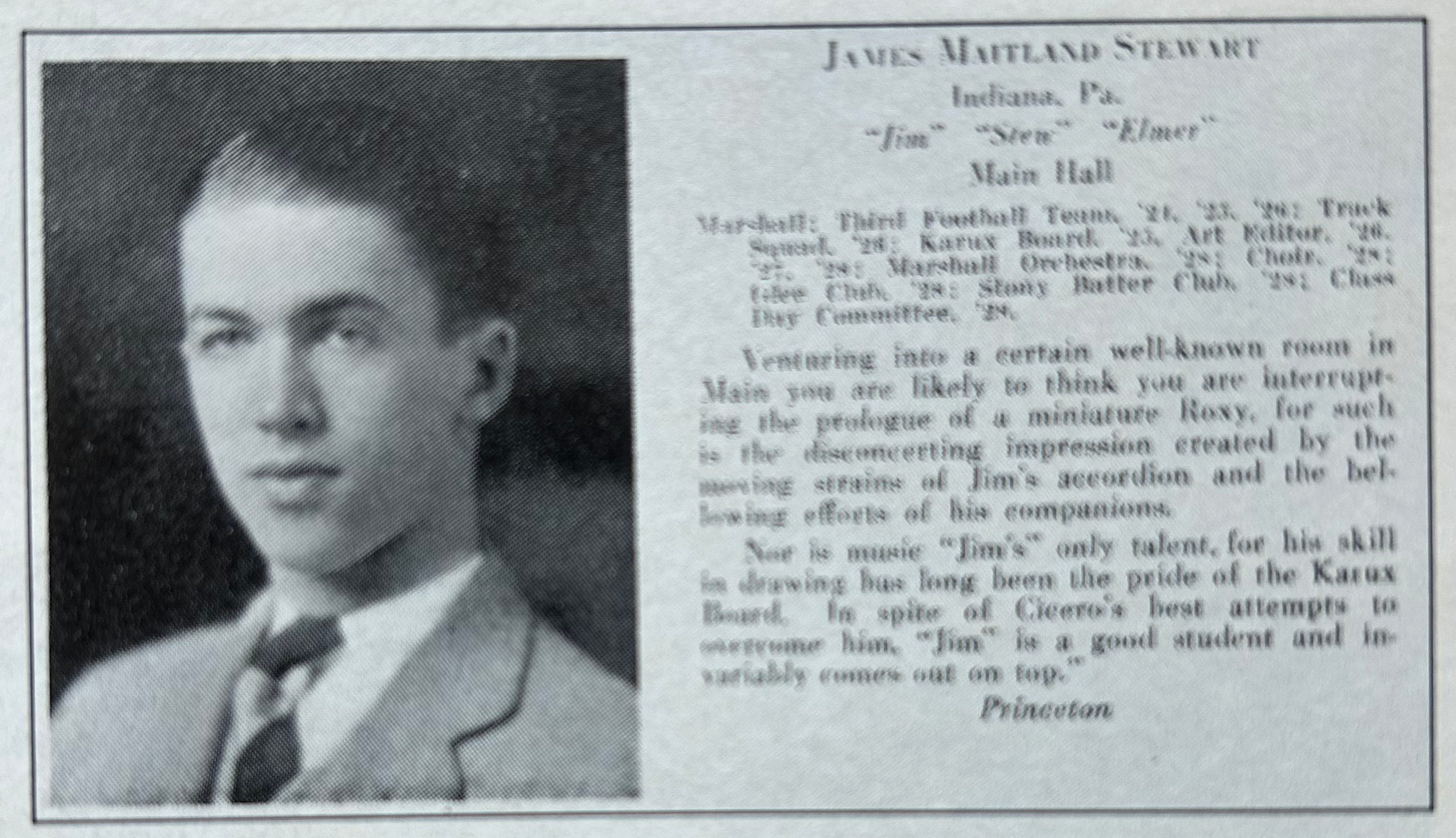

When James Maitland Stewart was born in May 1908, Indiana was a thriving coal-mining town. His family could trace its roots there back to the first white settler in the area. Jimmy was the first child and only son (two daughters followed) of Elizabeth and Alex Stewart, a member of the Princeton Class of 1898. From his mother, a soft-spoken and devout woman, Stewart is said to have inherited his deliberate, halting speaking manner; from his father, a fondness for the theatrical.

Alex Stewart was deeply conservative, Presbyterian, and patriotic. He left Princeton to serve in the Spanish-American War. When America entered World War I, he enlisted at age 46 and served in the infantry. On the home front, 10-year-old Jimmy wore a miniature soldier’s outfit and produced patriotic plays, which he performed in his basement for his friends.

The elder Stewart owned the town’s hardware store, which had been in the family since the Civil War. Alex Stewart often took odd items in payment, like a live 12-foot python offered by a traveling circus, and sometimes added them to his display of curios in the front window. From a young age, Jimmy had a passion for flying. As a child, he built model airplanes; at age four, he nearly killed himself attempting to fly off his roof in a go-cart “converted” for flight. One year, he whetted his thrill for aviation by saving up the $15 for a 20-minute ride with a traveling stunt flyer. In 1927, he traced Charles Lindbergh’s historic solo flight across the Atlantic using a map and a model plane in the window of the hardware store. (As an adult, he would portray Lindbergh in the 1957 film The Spirit of St. Louis.)

By contrast with the fictitious George Bailey, Stewart was practically thrust into a wider orbit from an early age. After ninth grade, Stewart’s parents sent him away to board at Mercersburg Academy, in south-central Pennsylvania. He had his eye on the U.S. Naval Academy, but he matriculated at Princeton at the urge of his father. There the gangly youth (he was 6-foot-3 and weighed just 130 pounds) switched from engineering to architecture after failing calculus, and discarded his football uniform for an interest in acting. He eventually landed the lead of the 1930-31 Triangle Club show, The Tiger Smiles, which was written and directed by his friend Josh Logan ’31. Logan, who went on to become a celebrated Broadway director, wrote in his autobiography that even then, Stewart spoke in his trademark stutter, and that he disdained acting as a career. “But he was so good,” wrote Logan. “I knew deep down he loved acting but was too embarrassed to admit it.”

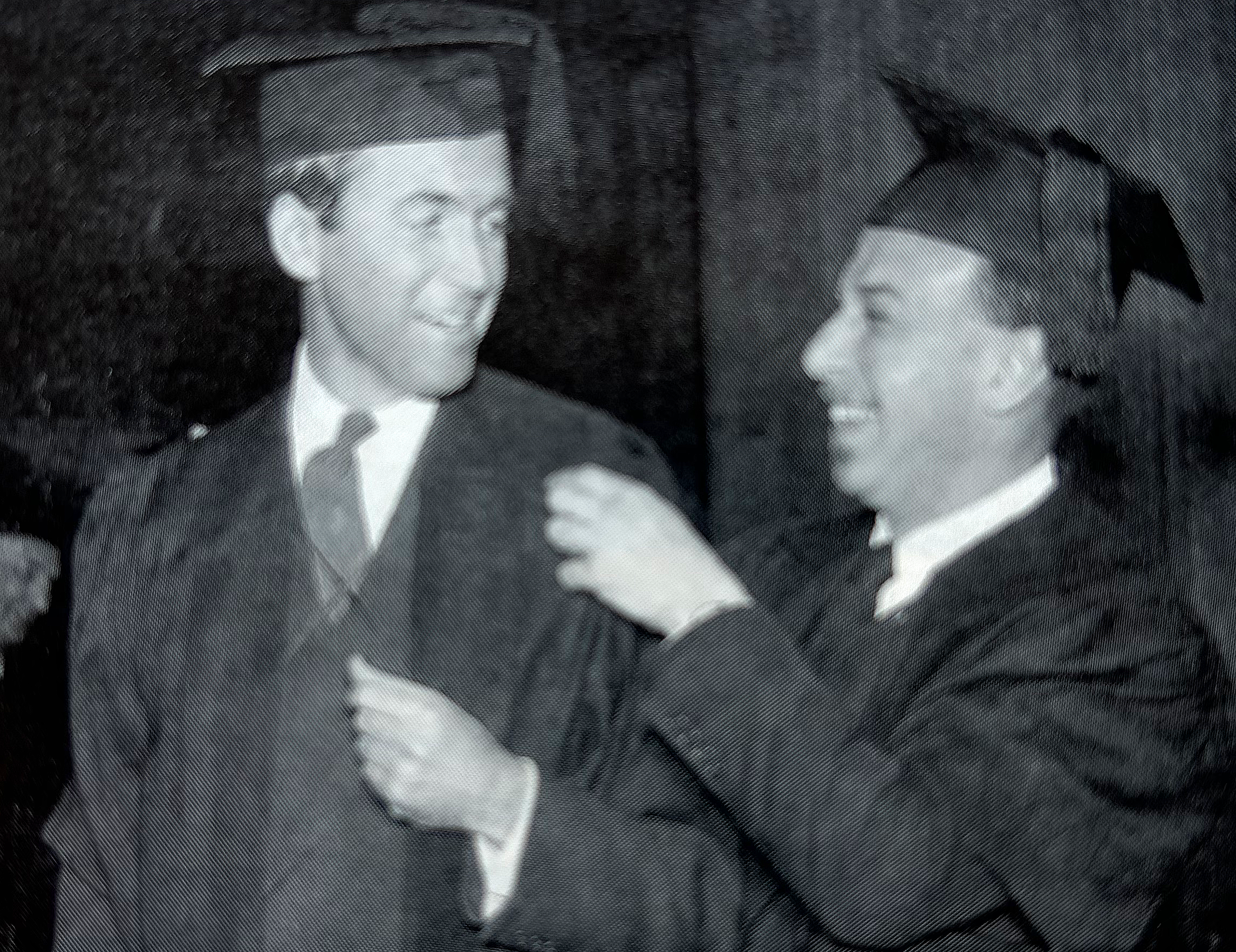

When Stewart graduated in 1932, during the Great Depression, prospects for young architects were poor. He faced a choice: accept a Princeton scholarship for graduate studies in architecture, or return home to Indiana to work in the family hardware business. Then his friend Logan invited him to join a theater group called the University Players, which was performing on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. What began as a summer lark led by that fall to small roles in Broadway plays, which led to bigger roles and eventually to a Hollywood screen test for MGM Studios. By 1935, Stewart’s earnings had soared from $35 a week on the stage to $350 a week making a half-dozen movies a year.

It was a respectable beginning, although, at first, MGM didn’t quite know what to do with this plain-speaking beanpole with a country-boy manner. The studios cast him as everything from a cynical reporter to a killer to a song-and-dance man. All this time, he roomed with his old buddy Henry Fonda, another veteran of the University Players, in a small house in Brentwood next door to Greta Garbo.

Stewart’s career path probably disappointed his father, but his parents followed each turn. They saw every one of his movies that came to town. His mother, Stewart once said, would go to all three showings of a film for three days running, to make sure she understood everything happening on the screen. Then she would write him with her impressions of his performance. “Dad made a paint of movie-going when a show of mine was in town,” Stewart once said, “but all m shows seemed to make him drowsy. When he talked to me about one of my pictures, I could always tell at which point he’d gone to sleep.”

Stewart’s persona as a good-hearted young man of common sense and integrity crystallized in his performance as Jefferson Smith, the naive country-boy-turned-Senator who went to Washington in Frank Capra’s 1939 film. Originally intended for Gary Cooper, the role created the mold for Stewart’s image on and off the screen, and earned him the prestigious New York Film Critics’ Circle Award. In Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Stewart portrays a quintessential Capra hero: a small-towner who defies a corrupt political machine in Washington, and ultimately triumphs by evoking the ideals of America’s Founders. Although the film’s view of America is open to interpretation, Stewart himself saw the character the way many of the film’s fans now recall it: “I was raised in a very definite conservative Republican philosophy. I suppose in Mr. Smith the film could be on the side of the common man and against big business, but to me it was only a matter of right or wrong.” Stewart invited to the public to see no difference between his acting persona and his true nature. “I have my own rules and adhere to them,” he said in a press release from that time. “The rule is simple but inflexible. A James Stewart picture must have two vital ingredients: it will be clean and it will involve the triumph of the underdog over the bully.”

When Stewart first moved to Hollywood, his family bonds seemed to stretch the 2,500 miles to Indiana. Having earned his pilot’s license, Stewart bought a single-engine plane so he could fly home for special occasions. For years he recorded his permanent address as 104 Seventh Street, Indiana, Pennsylvania. His parents also traveled West to see him. On one such trip, Alex was dismayed to discover that his son didn’t go to church on Sunday mornings. Alex left the house and returned in less than an hour with two men, elders of a Presbyterian church three blocks away. Stewart hasn’t stopped going since.

Although proud of his son, Alex Stewart never quite accommodated himself to his vocation. “Dad is 87,” Stewart said in a 1961 interview, “but he goes to work every day. I’m sure the main reason he’s kept his hardware store going is that he wants to have it ready for me to come back to, if I ever need real work instead of what he regards as make-believe work.”

For his work in The Philadelphia Story, Stewart won the 1940 Academy Award for Best Actor. On the night of his win, they story goes, after a swirl of post-Oscar parties, the actor took a call from his dad, who wanted to confirm that his only son had won “some kind of prize.” I heard about it on the radio,” Alex said. “Yeah, Dad,” his son replied. “It’s a Best Actor Award. They give ‘em out every year. I won it for The Philadelphia Story.”

“What kind of prize is it?”

“It’s a kind of statuette. Looks like gold but isn’t. They call it the Oscar.”

“Well, that’s fine, I guess. You’d better send it over. I’ll put it on show in the store where folks can take a look at it.” It remained there for the rest of Alex’s life.

Stewart did not have much time to enjoy his renown. With war raging in Europe, he had decided in the fall of 1940—more than a year before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor—to enlist. He was the first Hollywood star to do so, even though at age 32 he could probably have avoided the draft.

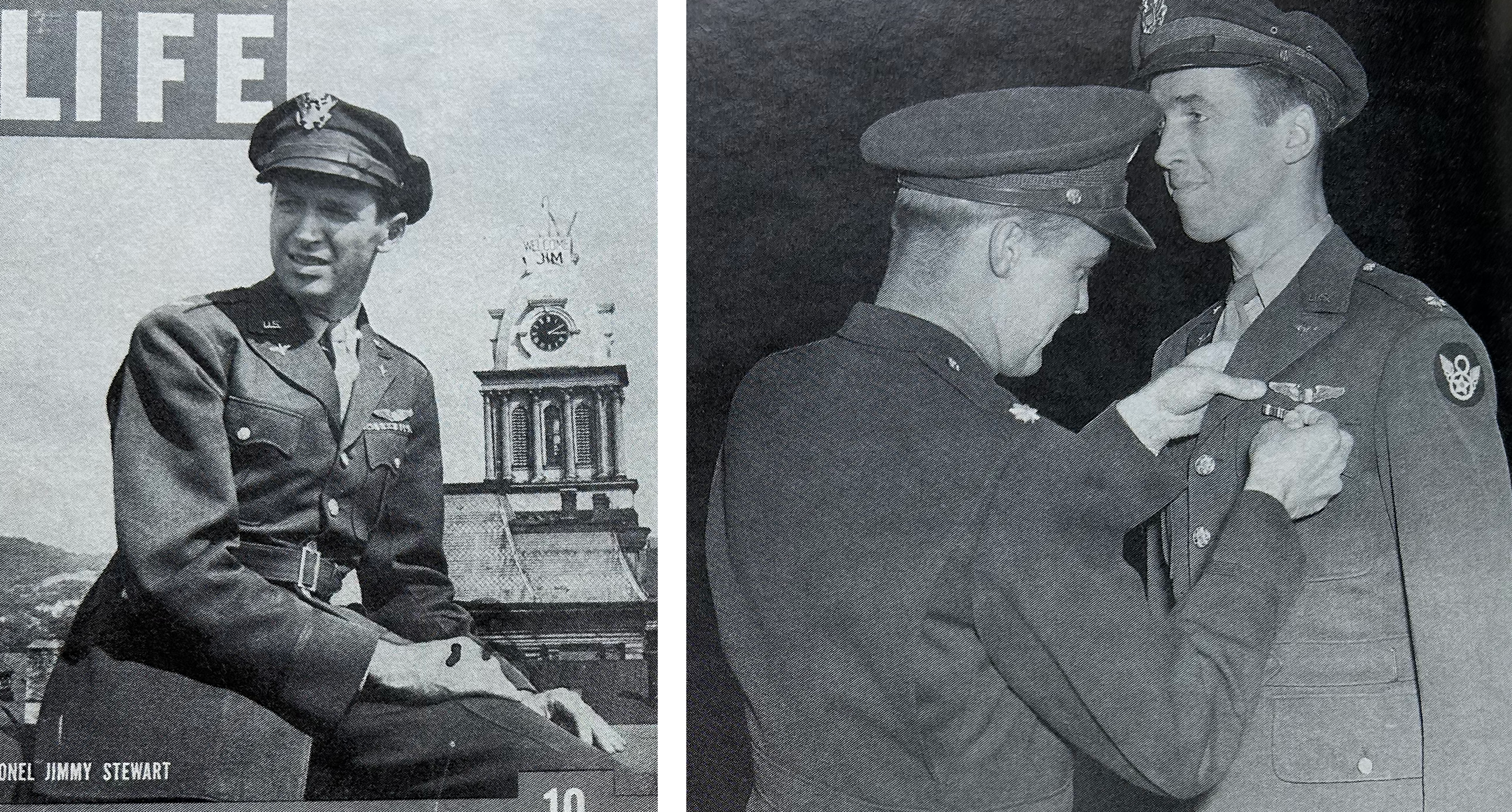

One of the most prominent exhibits at the Stewart Museum is the wall that highlights the actor’s war service. That experience suggests more than anything else that Stewart’s persona was more than an image. He served more than four years in the military, first as a flight instructor, then as a B-24 pilot. Based in England during the last two years of World War II, he led a bombardment group on more than 20 missions over Germany and occupied France. For his service, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Years later he told an interviewer that his military experience meant much more to him than his movie career—perhaps because it meant so much to his father.

In November 1943, when he was due to leave for England, his father came out to Sioux City, Iowa to see him off. Never a demonstrative man, his father slipped a note into his pocket for him to find during his flight:

My dear Jim boy. Soon after you read this letter, you will be on your way to the worst sort of danger….Jim, I’m banking on the enclosed copy of the 91st Psalm. The thing that takes the place of fear and worry is the promise of these words. I am staking my faith in these words. I feel sure that God will lead you through this mad experience….I can say no more. I only continue to pray. Good-bye, my dear. God bless you and keep you. I love you more than I can tell you. Dad.

Stewart’s squadron routinely returned with fewer planes than went out. With flak bursting around him he would remember the words of the psalm his father had given him, “thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that flieth by day;…He shall give his angels charge over thee.” Stewart went regularly to the base chapel. “Many men I flew with were being killed in action,” he recalled. “Religion meant a lot to me for the rest of the war.”

When Stewart was finally mustered out, Life magazine memorialized his arrival home with a cover story. “In New York, Stewart refused a hero’s welcome,” Life reported. “Instead he drove off to his old hometown of Indiana, Pennsylvania. There in his parents’ comfortable red brick house on a hill overlooking the town, he slept late, played the piano and joked with his father about the old days. …Stewart himself vetoed plans for an elaborate celebration suggested by the Chamber of Commerce.” He remained in the Air Force Reserve until the 1960s, retiring as a brigadier general.

Stewart felt some ambivalence about his return to acting more than four years in the service. The talent was still there, but he doubted his commitment. During the shooting of his first postwar film, Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, he wondered aloud if acting was a “decent” pursuit. Lionel Barrymore, a fellow cast member, challenged him by pointedly asking whether he thought it was more “decent to drop bombs on people than to bring rays of sunshine into their lives” with his acting talent.

This barb, and the realization that he was still a good actor, wiped away his doubts.

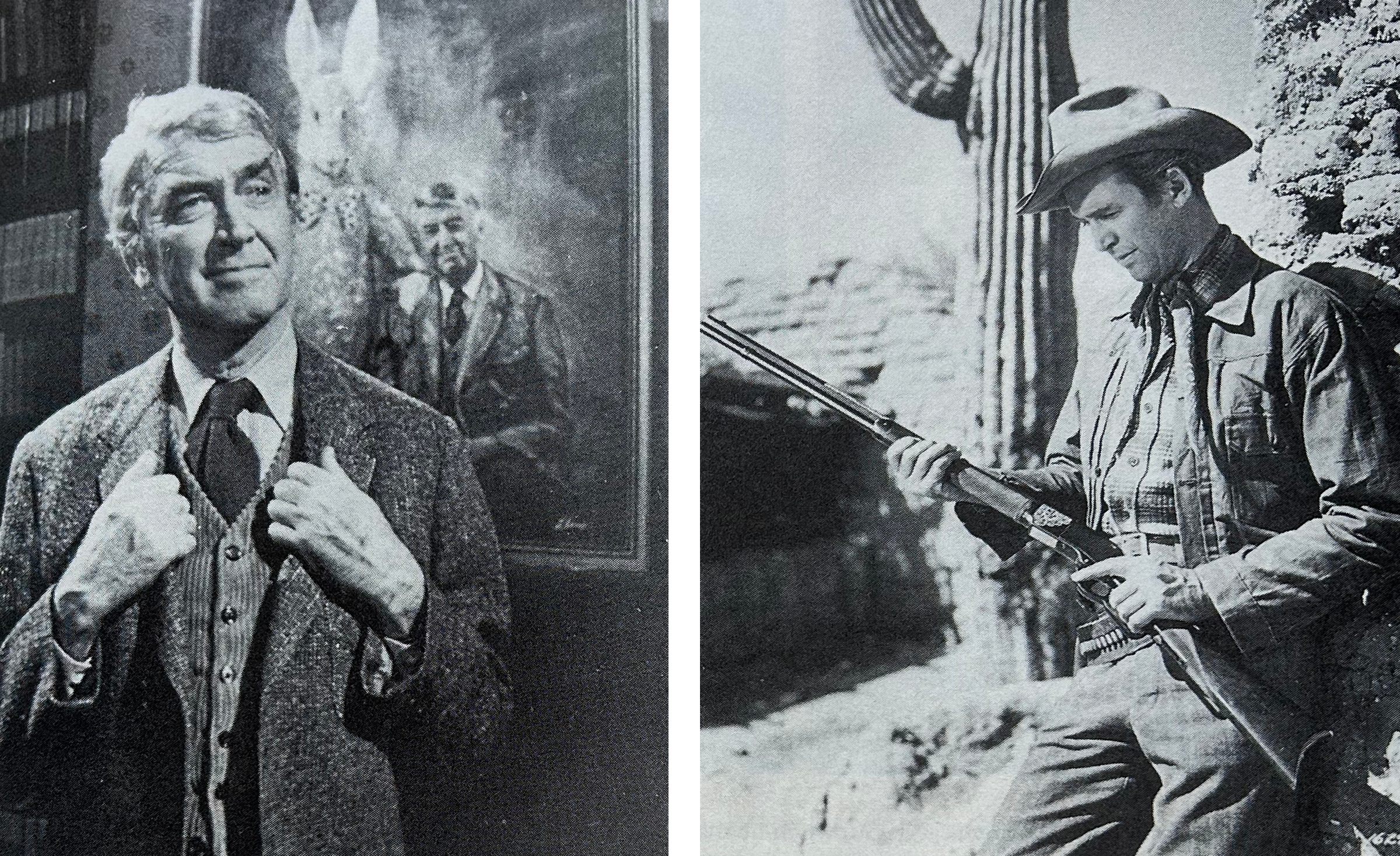

Despite Stewart’s now legendary performance in the role of George Bailey, It’s a Wonderful Life at the time drew mixed reviews and flopped at the box office. Like Stewart, America had changed since he had last appeared on screen, and his idealistic persona seemed out of fashion. But success eventually returned with the 1950 hits Harvey, a light comedy, and Winchester 73, Stewart’s first Western. In the latter, he revealed a new dimension to his acting—intense, violent, edgy—that his portrayal of the mercurial Bailey had only hinted at.

One of the joys of wandering the Jimmy Stewart Museum is the opportunity to mull over the sources of Stewart’s enduring appeal. The actor Anthony Quayle once said of Stewart: “He projected America’s favorite self-image: modest rectitude.” After seeing him in an early film, Frank Capra said later, “I sensed the character and rock-ribbed honesty of a Garry Cooper, plus the breeding and intelligence of an Ivy League idealist.” But as the Stewart Museum reminds us, these comments were true only of his early performances.

From the very threshold of the museum, where a poster from Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller Vertigo (1958) greets visitors, the chronological galleries testify to the versatility of Stewart’s acting style. Movie posters, props, and original script remind the discerning Stewart buff of the string of roles that replaced his early stereotype with men of hypocrisy, vengefulness, desperation, moral ambiguity, and obsession: Rope (1948), Rear Window (1954), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), Anatomy of a Murder (1959), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

Stewart’s unique gift was a natural, casual style. Said Cary Grant, “The reason he stood out from other actors was that he had the ability to talk naturally….Some years later, Marlon Brando came out and did the same thing all over again. But what people forget is that Jimmy did it first.” Above all, Stewart was professional and diligent in his preparation. From his father he knew the spiritual value of hard work.

The museum’s biographical exhibits show that community and family roots can even be transplanted to Beverly Hills. To be sure, Stewart indulged his bachelor status into his 40s, and over the years he was romantically linked with Margaret Sullavan, Ginger Rogers, Olivia de Havilland, Dinah Shore, and Marlene Dietrich, among others. But Stewart finally settled down in 1950, when he married Gloria Hatrick McLean, a younger woman with two children from a previous marriage; they had twin girls and remained happily married until Gloria’s death in 1994.

In explaining his fondness for his hometown, Stewart in 1958 pointed to the fact Indiana “has been, and still is, the headquarters for Mr. Alex Stewart and his family. My father has been almost fanatical in his determination to keep our family together—and he has one it.” Stewart’s mother had died in 1954, and Alex followed in 1961, at the age of 87. The hardware store soon closed. In 1969, it was razed to make room for a bank, but a sundial and inscription still mark the spot where the store once stood, its gleaming gold statuette anchoring an immodest and ever- growing display of a father’s pride in his son.

Stewart’s trips home since the 1960s have been infrequent. In 1983, the town feted his 75th birthday and unveiled the eight-foot bronze likeness. The statue captures a quintessential Stewartian pose: one hand in his pocket, the other outstretched with a finger raised, as if to emphasize a point in conversation.

When he was first approached in the early 1990s with the idea of a museum in his honor, Stewart resisted—out of modesty, it seems. But Jay Rubin, a local lawyer and film buff, eventually won him over by pointing out that a museum could give the ailing town an economic boost. Stewart’s approval was conditional: he didn’t want his affluent show-business friends solicited for donations, and he insisted the museum be housed downtown.

The museum is as much his gift to the town as vice versa. It gave a struggling community a chance to come together around an important project, and the community responded. To make way for the museum, the Masons offered to move out of their lodgings on the third floor of the local library. The site needed a complete renovation and offered only 5,000 square feet of space, but its size and location guaranteed an appropriate modesty and intimacy. Two local banks arranged for lines of credit to finance the renovation. Jay Rubin donated most of the movie posters that line the galleries. Student volunteers from the local vo-tech school supplied a lot of the elbow grease for the renovation, until it became clear that the museum needed professional contractors to finish the job on time. Universal Studios donated audiovisual equipment and sent a technician to install it. Stewart himself donated a number of mementos from his career, including one of his two Oscars.

From a single spot in the southeast corner of the museum, a visitor can look through a window and see four major Stewart landmarks: the bronze statue in front of the courthouse next door; the clock tower of the old courthouse down the street, made famous by the Life magazine cover photograph; the sundial that marks the site of the old hardware store across the street; and (when the foliage does not obscure the view) the former Stewart homestead up on Vinegar Hill.

On the museum’s opening day in May 1995, Stewart’s old friend Bill Moorhead spent much of the morning in that corner, politely answering questions and smiling under the hubbub. Now in his 90s, Moorhead is the last of Stewart’s Indiana contemporaries, and his strongest link to Indiana. Through him, Stewart followed the progress of the museum, which took several years to complete. And through him, Indianans have followed with concern the decline in the 88-year- old star’s health and spirits since the death of his wife two years ago.

It takes only a few minutes to walk through all the galleries of the Stewart Museum. Yet in a sense, the final gallery is the one that surrounds the building and spreads out among the Pennsylvania hills. In the fictitious Bedford Falls, the town feared the green of one unscrupulous banker. Indiana, on the other hand, has suffered from inexorable economic trends and poor planning. In the last 20 years, most of the mines have shut down as the extraction of coal became prohibitively expensive. Throughout the 1980s, the region suffered one of the highest unemployment rates in Pennsylvania, and many of its downtown storefronts remain vacant.

Just as Stewart in the 1940s had seen the importance of broadening his range as an actor, his hometown has awakened to the need to diversify its economy. A town that once exemplified timeless virtues and self-sufficiency now turns to the outside world for salvation. Indiana has a municipal airport, built with federal subsidies, and a brand new air terminal—named for Jimmy Stewart—to draw economic development and provide an easy commute to Pittsburgh, 40 miles to the west. But its economic future will depend greatly on the tourist trade. In its first year of operation, the museum attracted 9,000 visitors, and the staff continues to refresh the museum’s

appeal. It is training guides to talk knowledgeably about Stewart’s life and developing educational programs for children. The Stewart museum will not by itself save Indiana, but it is expected to bring in tourist dollars. The unemployment rate in Indiana County is now below 10 percent for the first time this decade. Retail and service businesses are moving into the area.

This year marks the 50th Christmas since the release of It’s a Wonderful Life. Earlier this month, Indiana celebrated by recreating the look of Bedford Falls. Philadelphia Street was redone for the occasion with 1940s-era details, and a parade featured members of the film’s original cast and crew.

When one visits Indiana and the museum, it is tempting to play the George Bailey game in reverse. What would this town have been like if Jimmy Stewart had never “shaken the dust” off his feet and left for Mercersburg Academy and Princeton, for Broadway and Beverly Hills, for a wonderful life that most of us would envy?

It wouldn’t be much different. Perhaps J.M. Stewart Hardware would still anchor the corner of Philadelphia and Eighth streets. Maybe Stewarts would go on populating the local schools and churches. But the town would still be struggling, welcoming Wal-Marts and espresso bars and seeking other ways to bring dollars into local cash registers. Yet the loss of its talented son seven decades ago was ultimately the town’s gain. Stewart’s life has been a boon both to art and the principle that a life lived honorably is a tribute to the community that shaped it.

This was originally published in the December 25, 1996 issue of PAW.

No responses yet