In A World at War

In His Opening Address President Dodds Asks For a Rapid Mobilization of Power

It has been my habit on occasions such as this to confine myself primarily to educational problems or phases of campus life in which we as members of a university have a particular part to play. However, I conceive it appropriate this afternoon to depart from this custom because the time has come for us as a nation, as a university, and as individuals, to face up to a clear-cut decision on America’s place in a world at war.

It is my firm conviction that the United States should abandon the policy of drift and the psychology of passive defense which has characterized us for the past two years and without qualification or mental reservation marshal the full strength of our national power against a totalitarian Axis, in such ways and with such resources as are most likely to assist to a prompt and unequivocal victory those nations now at war with her. This conviction is not dictated by any sentimental regard for other nations; it springs from the realization that our national self-interest, in fact the survival of America as we know it, demands it.

For two years now American citizens have been discussing this issue. There has been debate without stint on every aspect and, as is natural, it has frequently been most heated on irrelevant questions. But events are rapidly contracting the field of discussion for those who value the traditions and ideals of America. For a nation, as for individuals, yesterday’s decisions and actions limit the range and freedom of action today. To this extent everyone’s freedom at this moment is modified by what has happened as recently as a few days ago, and what is necessary to preserve for the future the great corpus of our liberties. The moment has arrived to realize that for those who believe in America the range of debate is narrowing in favor of clear-cut, courageous action if the human values that are America are to remain American.

The time has come to forego our cherished habits of leisurely criticism of tangential matters in the interest of conserving our full national potential for self-preservation. If our democracy cannot discipline itself to this truth, Hitler’s contempt for us will be well-founded.

For two years now citizens have aired all sorts of views on various aspects of the present situation. When all of it has been sifted, one central fact remains: the civilization expressed by our American way of life has been arrogantly challenged by a hostile philosophy.

What is this civilization that is being threatened? It is difficult to express what we mean by the term civilization, and I shall not attempt to define it today. It is even harder to measure its advance by objective tests. But one standard of measurement that can be applied, among many others, is the progress that society makes towards the elimination of irresponsible privilege. Privilege rots the privileged; it is not even good for them; and its existence is a constant enemy to peace and stability.

Democratic and undemocratic systems differ in this. The former denies that there is any closed social, political or economic group to which society owes allegiance. The latter insists that there is. The democratic ideal recognizes the need of leaders; it knows that all men are not created with identical natural endowments, but it requires that the leaders be selected by free competition of capacities in an atmosphere of social mobility between group and group.

Because in a world of human frailty the best that any democracy has achieved in this direction falls short of the ideal, we are apt to forget how far American traditions and institutions have moved toward it. To cite but one example, our ever-expanding public school system, with all its imperfections, represents — if its full implications are understood — a big stride forward in world history.

Democratic government seeks to assure the release of a nation’s full endowment of individual capacities by keeping clear the channels of opportunity. Granted that it is but a rough and ready device; granted also that its function is the unspectacular one of maintaining equilibrium among social pressures, it is by far the best that the world has yet produced for this purpose.

Life or Death Struggle

Now, after years of undisputed ascendancy our inherited ideals of human dignity have been thrown into a life or death struggle with a new dynamic order which exalts the privilege of the few at the expense of the many. This vigorous but ruthless philosophy claims a divine right of privilege for its own self-chosen individuals and for its own self-chosen nations. These self-selected privileged individuals repudiate all external controls. Rather do they consider themselves to be superior to the ordinary ethical principles which govern relations between people in civilized communities. Their theory of government, and they themselves are the government, tolerates no ethical and legal restrictions whatsoever. Under their philosophy there are no moral limits for those who have the power to ignore them.

It was possible to persuade millions of people to accept this uncivilized doctrine only because they had previously transferred the initiative for their lives from themselves to the state, and because as children of Mother Government (whom they trust but cannot control) they are willing to give her the full freedom of action which she demands, without trammeling her with “grubby moral considerations.”

The difference between that philosophy and ours may be described by saying that the issue turns on the question as to where initiative and control in human life shall be lodged. Is there to be a continuous growth towards wider distribution of power and privilege among people and nations, or are power and privilege to become the property of a single man, or oligarchy or nation which claims to transcend ordinary morality because it acts in the name of government? The decision involves a great deal more than the pros and cons of economic planning.

A system which transfers to any political leader or government untrammeled initiative for life, as distinct from regulation of the conflicting interests which arise from multiple initiatives, may come into power in the guise of democratic processes, but it cannot long remain democratic.

If the struggle were merely a matter of competition between two ideological views of life, to be settled in free discussion on the merits, we Americans might relax, secure in the justice of our cause and in the ultimate triumph of reason.

No Peaceful Persuasion

But he is indeed an innocent person who believes that the outcome will be decided by peaceful persuasion. The raw fact is that the hostile way of life which threatens us is backed by immoral physical force of unprecedented proportions. This carries the struggle from the realm of ideas into the realm of force. It will be decided in this realm and the decision will be binding for a long time to come.

It is proper to emphasize ideals; no nation can live without them. It is because our ideals at this moment are in confusion that our force is still being dissipated and our will to force is still weak. But those who say that force never settles anything are in self-inflicted error. High ideals can be corrupted and destroyed by force if force is permitted to destroy the men and the institutions which embody those ideals. That America by geographical position is immune from aggression by force is a terrible misconception. If one projects into the next decade the curve of world armament developments of the past ten years this fact becomes clear.

Defeat Without Invasion

We may be defeated by force without a single enemy soldier landing on our shores. For there is a more abstract but none the less real side to the possible invasion of America than can be expressed in terms of armament and territorial invasion. Nothing succeeds like success. If totalitarianism succeeds militarily and commercially on the Continent of Europe (and if it is successful in arms I find every reason to believe that it will succeed economically as well), it will be imitated elsewhere. Styles in government are copied as are styles in clothing. The commercial and military position of the United States in the Western Hemisphere and that of Great Britain in the rest of the world gave democracy a reputation for prosperity and greatness which undoubtedly influenced the people of other nations to demand popular government for themselves. In like manner a victory in arms for totalitarianism will encourage a world epidemic of totalitarianism, of which there are signs already.

So I concluded that when those holding a view of life which threatens a higher and more idealistic view resort to overwhelming force to make that view prevail, the competing way of life can survive only if it is courageous and virile enough to resist by force. For this reason I believe that we can no longer delay our decision in favor of aggressive defense. World movements will not permit America to retire to a hill-top to live her life in some quiet, ideological retreat as one might retire to a monastery. We can no longer afford the luxury or momentary comfort of such a picture of America.

Princeton and War

How the campus should conduct itself from “here in”; how the University can best serve the State; how it can best weather the storm of adjustment of its resources and curriculum to unprecedented conditions are problems on which the experience of the last war throws little light. But we have glorious precedents to sustain us. In 1776 Princeton under President Witherspoon wagered its all for human liberty at a time when many people of substance and influence were trying to come to terms with both sides.

Again in 1861 the outbreak of the Civil War recalled half of our students to their homes in the South, and the story of how they departed with the admiration and affection of their fellow undergraduates, equally loyal to the cause of the North, is one of the most memorable chapters in Princeton history. The impact of the Civil War on Princeton was all but disastrous, but she survived through loyalty, thrift and hard work, and she will survive this unknown that we face today.

Meantime the resources of this University — organization, men, facilities, and equipment — are committed to the use of the Country, whenever and however needed, in the present crisis.

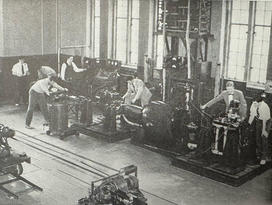

Right now Princeton scientists are engaged in research on war projects, the number and importance of which are out of all proportion to the University’s size and resources. Others are doing double duty, giving special training programs to help meet the acute shortage of trained technicians in industry. Economists and political scientists are at work in the extensive civil agencies that are required in modern war.

In addition our scholars are striving by means of longer work-days to maintain our high standards of instruction, realizing that the maintenance of a continuous flow of trained men is essential to a national defense program of unknown duration, as well as of importance in the days of reconstruction that must follow.

Our alumni are responding to the nation’s need in the same characteristic way that Princeton men have always done since the birth of the nation. The list of older alumni in high military, civil, or technical posts in the national defense program is an impressive one. The University is no less proud of the class that was graduated in June, half of whom are in one or another of the armed forces.

And what of the undergraduates who are searching their should to learn where for the present their duty lies? The answer is clear: Remain at the task you have set for yourselves at Princeton. The President of the United States and other high officials of government have told you this. From personal conversation with some of them in Washington I know that they believe what they have told you and that their plans are framed to enable you to continue in college in so far as the broad considerations underlying the policy of universal service will permit. In earlier days of our nation’s history your duty to continue with your studies would not be so manifest. But conditions have changed since the time when the Civil War disrupted Princeton by calls for volunteers from both sides. As a nation we are more inter-dependent than we were then and we can each best contribute to national strength by fitting into the legally established plans for building that strength.

Your turn may come as it has come for those who have gone before you. The best way to prepare for that eventuality is to take full advantage of the present educational opportunities now accessible to you. In that way you will best serve the State, for modern war is technical and “total” and its demands are for well-educated and trained men in all fields. There are various special programs by which you can supplement your normal education to meet the military, technological, and civil needs of the moment; we hope to be able soon to announce some others.

The campus kept its head last year. Then students won my renewed respect for the fidelity with which they pursued the business which brought them to Princeton. Under strains and stresses that might have been an excuse for bad behavior they remained stable and self-possessed. Let us continue in this pattern this year. The conflict of opposing philosophies that I have discussed this afternoon, is not to be resolved by sudden impulse or by hysterics. Calm resolve and competent action are what will be needed. Let us all move forward in this spirit, confident that the genius of America is sturdy and sound and that, if we unite to use our strength for justice, the generation now in college will have earned its right to play its part in the development of a harmonious and happy America and to share in its abundance.

This was originally published in the September 26, 1941 issue of PAW.

No responses yet