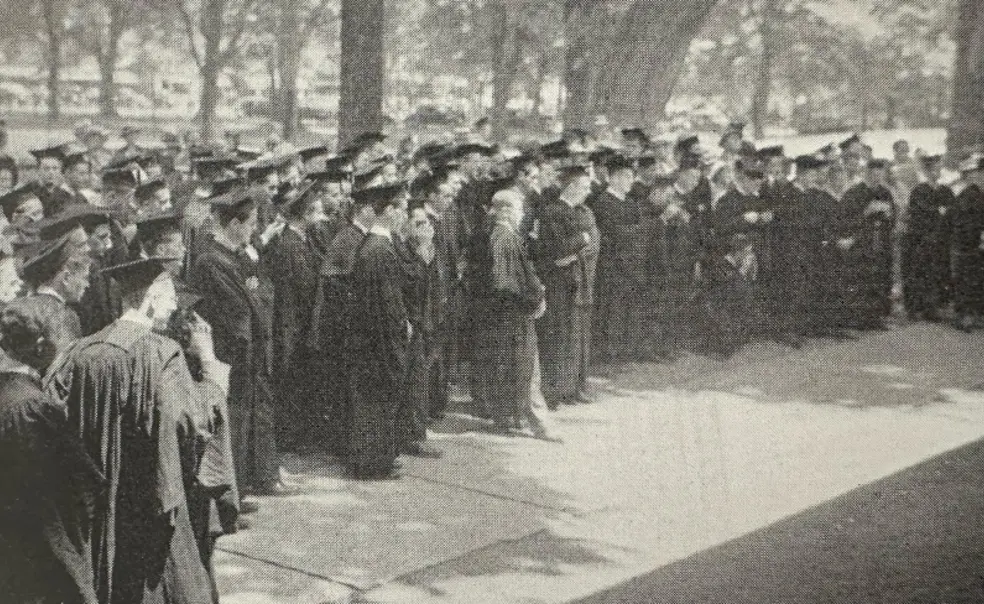

As we of the Class of 1941 gather for the last time as Princeton undergraduates, it seems fitting that we pause for a moment to consider the world which we are about to enter — a world which bears momentous implications for us and for those who will come after us.

This world present a disturbing and distressing picture. The disappearance of old values and the destruction of long-cherished ideas and institutions have been accompanied by the rise of powerful and terrifying forces which challenge our own way of life, at home and abroad. We do not call these new forces because they are not new; hatred, intolerance, the denial of moral values and human dignity are as old as man himself — yet these forces are attacking the mind of man and the soul of man with greater vigor than ever before.

The Unsure Present

We seek for peace among men and nations; yet there is no peace. We claim for man the ability to think out his own problems, the liberty to believe and speak as he chooses, and the right to govern himself; yet all over the world the lamps of freedom are being swiftly extinguished by authoritarianism in a variety of forms. We ask for man the opportunity to earn a decent livelihood for himself and his children; yet everywhere, even in the most prosperous of nations, there is economic insecurity, slavery and privation. The history of our times indeed will be written as a dark and turbulent chapter in the story of human progress.

As yet, we college men of today have had no part in the writing of that history. The advances which have been made and the errors which have been committed during the last twenty-five years must be entered upon the ledgers of time as credits or debits of another generation, and many, many more years will have gone by before historians will be able adequately to evaluate the events of the post-war era.

No, this world of today is not of our making; yet life is all too short for us to waste previous time lamenting and pointing the finger of blame at those whom we consider responsible for the chaos that is 1941. We are interested in past mistakes only for the lessons that they teach. Our true concern is with the future, and what it holds for us as individuals, as Americans, and as citizens of the world. How will the Princeton-trained youth, now assuming the responsibilities of full membership in a world at war, stand up under the strain and pressure of constant crises? Are we really prepared to meet this new world-situation which faces us today?

The 1941 Princetonian

This question of preparation for life offers an opportunity for us to clear away certain misconceptions about our university and its members. There are many unacquainted with Princeton, who persist in the notion that Princeton is synonymous with the raccoon coat, the hip-flask, and autographed slicker, and the jalopy — that our devotion to social pleasures precludes any serious study or thought. This is patently absurd; whatever “country club” atmosphere there may have been went under with the stock market in 1929, and has not reappeared. The Princetonian of 1941 is a student in more than name. He knows that there are problems to be solved — and problems of tremendous import, problems which have baffled the wise men of today and yesterday. He realizes that he will be at least partially responsible for their solution — and he is thinking about it.

Then, too, there are those who criticize the modern students as hyper-cynical intellectual shells, unwilling to stand up and fight for ideals because universal skepticism has rendered us incapable of possessing ideals; we are said to be ripe for plucking by the first opportunistic demagogue who will provide ready-made beliefs as a smoke-screen to cover his urge for power. This picture is no more accurate than the first.

We will readily admit that there has grown up since the last war a tendency to inquire carefully rather than to accept blindly — a healthy tendency, which we may perhaps credit to mounting interest in the study of psychology and public opinion. But merely to say that we are inclined to question ideas and convictions certainly does not mean that we necessarily reject them, that we have reached the wretched state of complete disillusionment. We are all idealists in one way or another, and if there is anyone among us who feels that he is without ideals, it is probably because he has never stopped to think about having any; it is nothing that a good two hours of undisturbed introspection cannot cure.

No Basis

These misconceptions of Princeton as a playboy’s paradise or a school for cynics are without foundation. They may be easily disproved by the first-hand observation of Princeton life as it is really lived here on campus.

Still Another

But there is still another challenge to the value of a Princeton education — a challenge which cannot be so quickly dismissed. We are asked: What if you Princetonians are serious students and earnest thinkers? What if you do have your own ideas and convictions? If, after four years of pleasant life in the cloistered academic atmosphere of a university, you are deposited in a world of strife and turmoil, a world more savage than ever before, can you make the transition without mental dislocation, emotional disturbance, or physical weakening? Can you, Princeton men, emerge from your “ivory tower” to meet the impact of this new situation and fulfill the duties of life, no matter what they may be?

Each of us must answer these questions by his own actions, and the answers which we do give will determine the truth or fallacy of the proposition that Princeton, while preserving a character of her own, far different from that of the world at large, can train men to take their proper and useful places in whatever way of life lies before us.

The Answer

Gentlemen of the Class of 1941, you and I know that there is but one answer. Yes, the Princeton men of 1941 will take their places in the world as Princeton men have always done — with vigor, with loyalty, with fortitude — no matter how dark the outlook may appear.

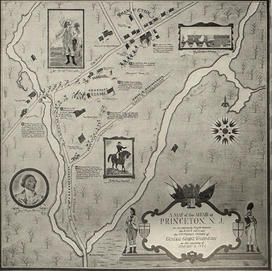

And in the America of tomorrow, as in the America of today and yesterday, Princeton men will be leaders in all fields of endeavor — for we have not forgotten the glorious examples of James Madison, Woodrow Wilson, and those other distinguished graduates, living and dead, who have so firmly established the concept of Princeton — the national institution. The ideals we have learned here in the past four years, from men whom we are proud to call friends as well as teachers — the ideals of human dignity and human progress, the individual’s freedom to think, speak, and worship God as he chooses, the supremacy of reason, logic and interchange of opinion over emotion, sophistry and brute force — these are the very things for which this weary world of ours has waited far too long. Our course has been set by these stars — and only by holding that course unswervingly in the difficult days and years ahead can we provide enlightened leadership for our generation. This is what Princeton expects of her sons; we can do it, we must do it and we will do it.

This was originally published in the July 7, 1941 issue of PAW.

No responses yet