A writer and his times

Joseph Frank explores Dostoevsky’s life and the issues raging in Russian society

The Russian writer Feodor Dostoevsky led a life as dramatic as his novels. Born in Moscow in 1821, he saw a promising literary career interrupted when he was arrested for being part of a liberal political group and sentenced to death. He was actually standing before a firing squad when his punishment was commuted to four years of hard labor in Siberia, followed by six years of mandatory military service.

Dostoevsky started writing again when he returned to St. Petersburg in 1859. In the remaining 22 years of his life, he wrote several major novels, including Notes from Underground, Crime and Punishment, and The Brothers Karamazov, despite suffering from epilepsy and a gambling addiction. The books’ brooding characters, complex plots, and passionate philosophical debates have endeared them to generations of readers and earned them a central place in the literary canon.

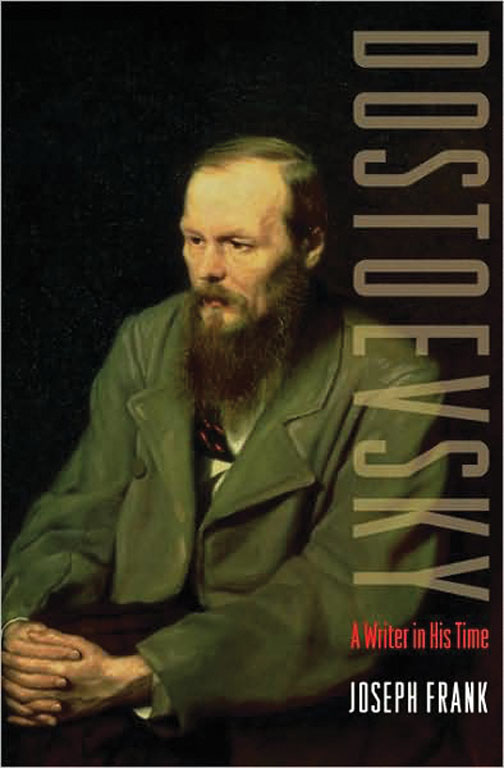

Joseph Frank, a professor emeritus of comparative literature at Princeton, interweaves the story of Dostoevsky’s life, the intellectual and political context in which he wrote, and close readings of his novels in Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time, the capstone to Frank’s 50 years of studying the author. Much of that effort came at Princeton, where Frank taught from 1966 to 1983, and it resulted in a work that critics have hailed as one of the finest literary biographies of the Russian writer ever written.

Frank, now 91 years old, was a graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1954 when he was invited to give a series of lectures for the Christian Gauss Seminars at Princeton. He planned to speak on French existentialism, the movement led by then-contemporary writers Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, and for historical background he read Notes from Underground, which Frank found so compelling that he learned Russian so he could study it in the original. Frank spent two decades researching Dostoevsky before publishing five volumes on the novelist between 1976 and 2002.

“I wanted to write a different kind of biography which was more focused on the whole situation of Russian culture at the time, on the ideological ideas that were floating around,” says Frank, who moved to Stanford University in 1985 and still teaches a course on Dostoevsky. “I never thought I would write as huge a work as I did. I was going to write one volume, and then I realized it was impossible to express what I wanted to say in one volume.”

To reach a broader audience Princeton University Press pruned almost two-thirds of the text to produce Dostoevsky: A Writer In His Time, published last fall. Wall Street Journal critic Michael Dirda called the book “the essential one-volume commentary” on Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky had the rare ability to “fuse his private dilemmas with those raging in the society of which he was a part,” Frank writes, something the Russian author does in The Brothers Karamazov, where the murder of the three title characters’ father allows Dostoevsky to explore the role of religious faith in society. Frank describes the 19th-century Russian debates over that issue as well as over Russia’s relation to Europe and which political system the country should adopt — issues that formed a backdrop to the Russian Revolution of 1917 and still echo in Russia today.

“Being born in 1918,” Frank says, “I grew up in the shadow of the Russian Revolution, and was always fascinated by that event. Studying Russian cultural history in relation to Dostoevsky allowed me to satisfy my historical curiosity as well as my literary one, and my work actually combines the two.”

JULIAN E. ZELIZER Arsenal of Democracy: The Politics of National Security — From World War II to the War on Terrorism STEVEN S. GUBSER ’94 *98 The Little Book of String Theory Demobbed: Coming Home After the Second World War ALAN ALLPORT, SHEILA KOHLER, Jane Eyre Becoming Jane Eyre Silk Parachute JOHN MCPHEE ’53 The New Yorker

No responses yet