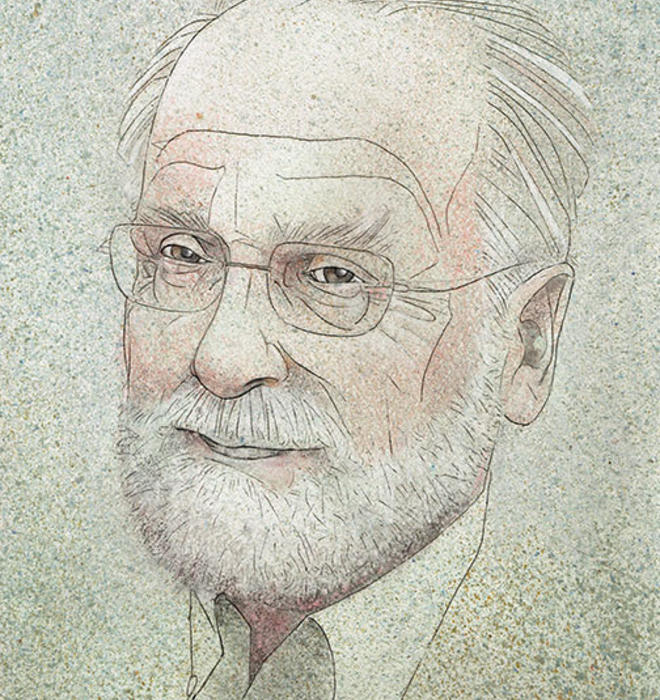

Writing with the Master

For Princeton journalists, praise from John McPhee was — and is — the ultimate reward

Editor’s note: Writer and professor John McPhee ’53, a pioneer of literary nonfiction, is scheduled to give a public lecture at 6 p.m. Nov. 12 in McCosh 50. For 40 years, young Princeton writers have said they considered their time studying with this master of his craft to be one of their most important and enduring experiences. PAW asked one of them — Washington Post journalist Joel Achenbach ’82 — to write about it.

John McPhee ’53 has many moves as a writer, one of which he calls a “gossip ladder” — nothing more than a stack of quotations, each its own paragraph, unencumbered by attribution or context. You are eavesdropping in a crowd. You take these scraps of conversation and put them in a pile. Like this:

“A piece of writing needs to start somewhere, go somewhere, and sit down when it gets there.”

“Taking things from one source is plagiarism; taking things from several sources is research.”

“A thousand details add up to one impression.”

“You cannot interview the dead.”

“Readers are not supposed to see structure. It should be as invisible as living bones. It shouldn’t be imposed; structure arises within the story.”

“Don’t start off with the most intense, scary part, or it will all be anticlimactic from there.”

“You can get away with things in fact that would be tacky in fiction — and stuck on TV at 3 o’clock in the morning. Sometimes the scene is carried by the binding force of fact.”

The speaker in every instance is John McPhee. I assembled this particular ladder from the class notes of Amanda Wood Kingsley ’84, an illustrator and writer who, like me, took McPhee’s nonfiction writing class, “The Literature of Fact,” in the spring of 1982. In February, McPhee will mark 40 years as a Princeton professor, which he has pulled off in the midst of an extraordinarily productive career as a staff writer for The New Yorker and the author of more than two dozen books.

When the editor of this magazine asked me to write something about McPhee’s class, I knew it would be the easiest assignment ever, though a little nerve-wracking. It was, because most of McPhee’s former students have saved their class notes and marked-up papers (Marc Fisher ’80: “I’ve never lived anywhere without knowing where my notes from his class are”).

When I meet Rick Klein ’98 at a coffee shop down the block, we examine forensically Rick’s class papers and the McPhee marginalia, the admonitions and praise from a teacher who keeps his pencils sharp. McPhee never overlooked a typo, and when Rick (now the hotshot political director at ABC News) wrote “fowl” instead of “foul,” the professor’s pencil produced a devastating noose.

McPhee’s greatest passion was for structure, and he required that students explain, in a few sentences at the end of every assignment, how they structured the piece. (McPhee noted on a piece Rick wrote about his father: “This is a perfect structure — simple, like a small office building, as you suggest. The relationship of time to paragraphing is an example of what building a piece of writing is all about.”)

Rick reminds me that the class was pass/fail.

“You were competing not for a grade, but for his approval. You were so scared to turn in a piece of writing that John McPhee would realize was dirt. We were just trying to impress a legend,” he says.

Which is the nerve-wracking part, still. He is likely to read this article and will notice the infelicities, the stray words, the unnecessary punctuation, the galumphing syntax, the desperate metaphors, and the sentences that wander into the woods. “They’re paying you by the comma?” McPhee might write in the margin after reading the foregoing sentence. My own student work tended toward the self-conscious, the cute, and the undisciplined, and McPhee sometimes would simply write: “Sober up.”

He favors simplicity in general, and believes a metaphor needs room to breathe. “Don’t slather one verbal flourish on top of another lest you smother them all,” he’d tell his students. On one of Amanda’s papers, he numbered the images, metaphors, and similes from 1 to 11, and then declared, “They all work well, to a greater or lesser degree. In 1,300 words, however, there may be too many of them — as in a fruitcake that is mostly fruit.”

When Amanda produced a verbose, mushy description of the “Oval with Points” sculpture on campus, McPhee drew brackets around one passage and wrote, “Pea soup.”

That one was a famously difficult assignment: You had to describe a piece of abstract art on campus. It was an invitation to overwriting. As McPhee put it, “Most writers do a wild skid, leave the road, and plunge into the dirty river.” Novice writers believe they will improve a piece of writing by adding things to it; mature writers know they will improve it by taking things out.

Another standard McPhee assignment came on Day One of the class: Pair up and interview each other, then write a profile. It was both an early test of our nonfiction writing skills and a clever way for McPhee to get to know his students at the beginning of the semester.

McPhee’s dedication to his students was, and is, remarkable, given the other demands on his time. One never got the sense that he wished he could be off writing a magazine story for The New Yorker rather than annotating, and discussing face-to-face, a clumsy, ill-conceived, syntactically mangled piece of writing by a 20-year-old.

He met with each of his 16 students for half an hour every other week. Many of his students became professional writers, and he lined up their books on his office shelf, but McPhee never has suggested that the point of writing is to make money, or that the merit of your writing is determined by its market value. A great paragraph is a great paragraph wherever it resides, he’d say. It could be in your diary.

“I think he loves it when students run off and become field biologists in Africa or elementary school teachers,” Jenny Price ’85 tells me. She’s now a writer, artist, and visiting Princeton professor.

McPhee taught us to revere language, to care about every word, and to abjure the loose synonym. He told us that words have subtle and distinct meanings, textures, implications, intonations, flavors. (McPhee might say: “Nuances” alone could have done the trick there.) Use a dictionary, he implored. He proselytized on behalf of the gigantic, unabridged Webster’s Second Edition, a tank of a dictionary that not only would give a definition, but also would explore the possible synonyms and describe how each is slightly different in meaning. If you treat these words interchangeably, it’s like taping together adjacent keys on a piano, he said.

Robert Wright ’79, an acclaimed author and these days a frequent cycling companion of McPhee, tells me by email, “I’d be surprised if there have been many or even any Ferris professors who care about words as much as John — I don’t mean their proper use so much as their creative, deft use, sometimes in a way that exploits their multiple meanings; he also pays attention to the rhythm of words. All this explains why some of his prose reads kind of like poetry.”

Just to write a simple description clearly can take you days, he taught us (once again I’m citing Amanda’s class notes): “If you do it right, it’ll slide by unnoticed. If you blow it, it’s obvious.”

We had to learn to read. One of his assignments is called “greening.” You pretend you are in the composing room slinging hot type and need to remove a certain amount of the text block to get it to fit into an available space. You must search the text for words that can be removed surgically.

“It’s as if you were removing freight cars here and there in order to shorten a train — or pruning bits and pieces of a plant for aesthetic and pathological reasons, not to mention length,” McPhee commanded. “Do not do violence to the author’s tone, manner, style, nature, thumbprint.”

He made us green a couple of lines from the famously lean Gettysburg Address, an assignment bordering on sadism. A favorite paragraph designated for greening was the one in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness that begins, “Going up that river was like traveling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings. An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest. The air was warm, thick, heavy, sluggish. There was no joy in the brilliance of sunshine.” (McPhee, in assigning this, wrote: “Caution: You are approaching what may be my favorite paragraph in a lifetime of sporadic reading.”)

One time the young Bob Wright used the word “minced” in an assignment. In their bi-weekly office conference, McPhee challenged Bob to justify the word. Bob offered his reasoning. McPhee looked up “minced” in the hulking Webster’s. “You found the perfect word,” McPhee declared.

McPhee’s career coincided with the rise of “New Journalism,” but he never was really part of that movement and the liberties it took with the material. A college student often feels that rules are suffocating, that old-school verities need to be obliterated, and so some of us were tempted, naturally, to enhance our nonfiction — to add details from the imagination and produce a work of literature that’s better than “true” and existed on a more exalted plane of meaning. We’d make things up. McPhee wouldn’t stand for it.

Amanda remembers being called into his office one day: “I could tell something was wrong because he wasn’t his usual smiling self. He had me sit down and glared at me a moment. Then he asked me very sternly whether I had made up the character I had allegedly interviewed for my paper that week about animal traps and snares — I’d talked to an elderly African American friend of my grandparents, whose snare-building skills helped him survive the Depression. Once I convinced him that Oscar was a real person, McPhee sat quietly a moment, then smiled and said it was one of the best papers he had received. Those were some of the finest words I’ll ever hear.”

Perhaps there are writers out there who make it look easy, but that is not the example set by McPhee. He is of the school of thought that says a writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than for other people. Some people joke about lashing themselves to the chair to get a piece of writing done, but McPhee actually has done it, with the belt of his bathrobe.

Here’s David Remnick ’81, the McPhee student who is now McPhee’s editor at The New Yorker: “You were working with a practicing creative artist, a writer of ‘primary texts,’ as the scholars say, but one who was eloquent, detailed, unfancy, and clear in the way he talked about essential things: description, reporting, structure, sentences, punctuation, rhythm, to say nothing of the emotional aspects of writing — anxiety, lostness, frustration. He didn’t sugarcoat the difficulty of writing well. If anything, he highlighted the bitter-tasting terrors, he cherished them, rolled them around on his tongue. But behind all that was an immensely revealing, and rewarding, glimpse of the writing life. Not the glamour or the readings or the reviews. No, he allowed you to glimpse the process, what it meant to write alone in a room.”

Marc Fisher, my Washington Post colleague, points out that part of McPhee’s magic was getting students to slow down. “He catches adolescents at exactly the moment when we’ve been racing to get somewhere in life, and he corrals our ambition and raw skills and somehow persuades us that the wisdom, the power, and the mystery of telling people’s stories comes in good part from pressing down on the brakes, taking it all in, and putting it down on paper — yes, paper — in a way that is true to the people we meet and the lives they lead.”

I doubt many of us ever took a class that resonated so profoundly over the years. Part of it was that McPhee felt invested in our later success, regardless of our vocations. You could knock on his door years later and confer with him about your writing, your personal issues, your hopes and dreams. How many teachers are willing to be Professor For Life?

These are tough times in my business, which the people in suits now refer to as “content creation.” Revolutionary changes in how we consume information have created challenges for anyone who is committed to serious, time-consuming writing, the kind that involves revision and the search for that perfect word.

But I don’t think anyone can obliterate the beauty of a deftly constructed piece of writing. This is particularly the case if you’ve written it yourself. It’s like hitting a great golf shot; you forget the shanks and slices and remember the one exquisite 3-iron.

One day in McPhee’s class, he praised a sentence I’d written about the Louise Nevelson sculpture “Atmosphere and Environment X,” near Firestone Library. He had me read it aloud. The hook was set. I don’t always think about it consciously, but that’s pretty much what I’ve been trying to do for more than three decades — write another sentence that might win the approval of John McPhee.

Joel Achenbach ’82 is a staff writer for The Washington Post and the author of six books.

5 Responses

Judson Jacobs ’93

4 Years AgoLove This Article

This is probably my favorite PAW article of all time. I’ve gone back and re-read it 3-4 times since it was initially published.

Catherine Stroud Vodrey k’26 k’57

10 Years AgoWriting to McPhee '53

I read with great pleasure the Nov. 12 cover article on John McPhee ’53.

Not only is John McPhee ’53 an extraordinarily talented writer, he is a fundamental part of a favorite Vodrey family story. In the 1960s or thereabouts, my grandfather Bill Vodrey ’26 wrote to Mr. McPhee, care of The New Yorker, to “correct” something he felt Mr. McPhee had gotten wrong in the magazine. Mr. McPhee promptly wrote back to my grandfather, thanking him for the information. My grandfather apparently took Mr. McPhee’s response as confirmation of some sort of editorial partnership, and he wrote three or four more times with other “improvements” to other McPhee New Yorker pieces. By the third or fourth offering, Mr. McPhee’s letter back to my grandfather read, in its entirety:

“Dear Mr. Vodrey: Who are you? Sincerely, John McPhee”

I recently wrote to Mr. McPhee myself regarding a New Yorker piece of his. He was kind enough to send a lengthy, handwritten response in which he remembered that funny letter he’d written to my grandfather. He is a class act.

Rob Goldberg ’79

10 Years AgoA Way with Words

Enjoyed the John McPhee profile. Just for the record, the 1977 version of that class, taught by Robert Massie, generated a remarkable number of writers and editors: Jim Kelly ’76 (Time managing editor), Susan Korones ’79 (Cosmopolitan editor), John Marcom ’79 (Time International president), David Michaelis ’79 (biographer), Ned Potter ’77 (ABC science reporter), Scott Redford ’78 (Islamic art professor, author), Randy Rothenberg ’78 (New York Times Magazine editor, author), Carol Wallace ’77 (historical novelist), Alex Wolff ’79 (Sports Illustrated senior writer, author), and Rob Goldberg ’79 (Wall Street Journal columnist, filmmaker, author).

Apologies for synopsizing great careers, and no doubt leaving someone out. But for sheer prose output, this group has published more than three dozen books, and enough column inches to choke a writing professor.

Dave Fulcomer ’58

10 Years AgoA Way with Words

I read with interest and a great deal of enjoyment the article about professor and author John McPhee. The article proved both enlightening and to a certain extent scary, as in 2009, I sent Mr. McPhee a copy of my memoirs covering my years as a student-athlete at Princeton in the mid-’50s. Earlier, I had read his article in The New Yorker (and later the book) about Bill Bradley ’65 titled “A Sense of Where You Are.” I was somewhat critical of a comment made in the article — that Mr. McPhee seemed very impressed that Bill Bradley could identify a basketball rim that was slightly off the mark as it pertained to its precise height. As an ex-hoopster myself, it was my experience that even a subtle deviation from the correct height was immediately obvious to the seasoned player. Other round-ballers I have questioned confirm this perception.

Now that I have read the article about Mr. McPhee, his approach to teaching, and his precision and expertise as a wordsmith, I am amazed that I had the chutzpah to send such a marginally crafted piece to such an expert. Ignorance is bliss! Beyond that, I went back into my personal archives and found his response, which was generous far beyond the merits of my recollections. Nice to have him “cut me some slack.” Thanks, John!

Kudos to PAW for recognizing the wonderful talent and humanity of this gifted author. I’m only glad that I read the article after the fact.

Max Morrow ’65

10 Years AgoA Way with Words

Joel Achenbach ’82, you’ve made The Master proud (cover story, Nov. 12). I read this beautiful piece alternately laughing and tearing up. You have made his wisdom, humanity, and mentoring skill come alive in a manner that I am sure resonates with all his students. A gem of the brilliance of John McPhee ’53 is enough to feel proud of Princeton and envious of those who could be taken to task by him.