The Year the Seniors Skipped the P-rade

Forty years ago, members of the Class of 1970 had other events on their minds

In that tumultuous spring four decades ago, when Princeton seniors skipped the P-rade and wore peace armbands in place of caps and gowns, when FitzRandolph Gate was thrown open and the first eight women graduated, when the cicadas whirred and Bob Dylan left with not only an honorary degree but a song, Stewart McBride ’70 and Raymond Gibbons ’70 played memorable speaking parts.

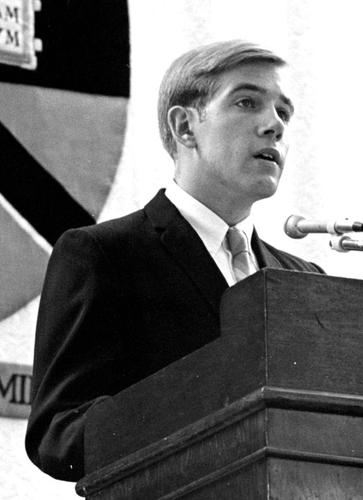

McBride, the class president, spoke to boos from some older alumni on Pardee Field at the conclusion of the P-rade June 6 as he sought to explain why most seniors had skipped the march into the alumni ranks. Gibbons, the valedictorian, bluntly sketched the rifts in society over war, inequality, and racism, then urged young and old to stop quarreling and do something about them.

Class president Stewart Dill (now McBride), left, Hal Strelnick ’70, and Michael Calhoun ’70, behind, lead graduates through FitzRandolph Gate after their Commencement. Most seniors skipped the traditional Commencement gowns and wore armbands symbolizing their desire to end the Vietnam War.

McBride was a football player and Woodrow Wilson School major who had applied for conscientious-objector status, been turned down, then flunked his draft physical. Gibbons was a Rhodes scholar, an aerospace engineering major from a blue-collar enclave in North Jersey who swept Princeton’s academic prizes and tutored minority youngsters in Trenton. He wasn’t politically active. “It’s fair to say I was busy studying, busy trying to enjoy the undergrad experience,” he says.

But Gibbons was upset by the Ohio National Guard shootings that killed four Kent State University students after campuses erupted in protest upon President Richard Nixon’s announcement of the invasion of Cambodia. Princeton students at a mass meeting in the Chapel on the night Nixon spoke were the first in the United States to go on strike. A Universitywide convocation attended by 4,000 in Jadwin Gym later declared institutional opposition to the war, and faculty gave students the option of skipping final exams and papers. “It was chaos. Things were changing on the fly. I was sympathetic to what was going on,” recalls Gibbons.

McBride — he was Stewart Dill at Princeton; he took the name of the woman he married — says, “Everything had been set in motion that night in the Chapel. There were teach-ins. ... A lot of people’s hearts and opinions were changing.” McBride presided over a packed meeting of the senior class in Alexander Hall on May 6. Class Day exercises, the step sing, the senior prom — jazz band leader Stan Kenton had been booked — all were scrapped. Going ahead “with the traditional celebrations and frivolity of graduation” did not seem right, he says. “A lot of us felt something different had to be done, not as a protest against the University” but against business as usual.

Classmates voted not to wear caps and gowns and to don armbands with a peace logo fashioned from class numerals. They erected a “Peace Tent” in the McCosh courtyard and instructed McBride to march as the class’s sole representative in the P-rade and to carry the class’s antiwar message to alumni. There was spirited opposition, especially to the P-rade boycott. Dozens of dissenters, including many of McBride’s football teammates, voted with their feet, marching in the rain that Saturday. Loud boos poured down when McBride rose to speak. “Though our class takes great pride in being a part of the Princeton family,” he said, “we have chosen by our approach to this year’s Reunions, and more immediately by our absence from this P-rade, to demonstrate our total opposition to the Vietnamese war and to the forces in the country which sustain that conflict.”

At Commencement, the only hissing was from the 17-year cicadas. “These are not easy circumstances in which to deliver a valedictory address. Our nation is divided at all levels as never before,” said Gibbons. “These are times of confrontation, rather than cooperation; of rhetoric, rather than dialogue; of self-righteousness, rather than understanding,” he said. The New York Times, under the headline “Seniors at Princeton Shun Tradition,” quoted his next words: “In an atmosphere where the decision to wear a cap and gown or an armband is suddenly politically significant, the educational achievements of valedictorians may not particularly qualify them to comment on the times. Yet any apolitical farewell address delivered on this occasion would be a peculiar anachronism.”

Coretta Scott King, widow of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and like Dylan an honorary-degree recipient, told Gibbons “she knew I was under great pressure and thought that I had risen to the occasion,” he recalls.

Gibbons went on to Oxford for a master’s degree in mathematics and later switched from biomedical engineering to medicine. A nuclear cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic and former president of the American Heart Association, he has championed evidence-based medicine (the idea of following clinical best-practice guidelines) and reforming the “distorted and perverse payment system” for health care. He remains, he says, “the idealist who started Princeton at age 16,” still trying to work for the greater good.

McBride became a journalist, wrote for The Christian Science Monitor and International Herald Tribune, and then became a digital media instructor and entrepreneur. Now single, McBride calls home a one-room, 12-sided yurt in Northern California’s redwoods, “where I write about sustainable agriculture, ride my Bianchi [bicycle], and sit silent Vipassana [meditation] retreats.”

In his speech that day on Pardee Field, McBride assured alumni that his class loved Princeton as much as they did. It repeatedly has broken Annual Giving records and become one of the most generous classes in Princeton’s history.

McBride’s path has only taken him back to Princeton a handful of times (including last fall for a gathering of the overachieving 1969 football squad that shared the Ivy title). But this 40th reunion had special meaning, for it gave him a chance to march in his second P-rade — and this time, with the rest of his class.

Christopher Connell ’71 is a freelance writer in Alexandria, Va., and former assistant chief of the Washington bureau of The Associated Press.

Raymond Gibbons ’70, then a 20-year-old senior and newly named Rhodes scholar, gave this valedictory address at Commencement June 9, 1970.

These are not easy circumstances in which to deliver a valedictory address. Our nation is divided at all levels as never before in our short lives. Students and parents debate the value of the strike; construction workers battle antiwar forces in the streets of New York; the executive and legislative branches of the government question each other’s authority. Voices are raised, tempers are aroused, the language on both sides grows more vehement, and, yes, even guns are fired, in Ohio, in Georgia, and in Mississippi. The appeals to love of country, on the one hand, and to conscience on the other grow ever more fervent, so that suddenly the peace symbol and the American flag are standards held far apart by their respective bearers, and everyone is urged to choose his side. Violence — whether by students, National Guardsmen, or construction workers — whether at home, in the Middle East, or in Southeast Asia — seems to be more and more an accepted phenomenon.

These are times of confrontation, rather than cooperation; of rhetoric, rather than dialogue; of self-righteousness, rather than understanding. In an atmosphere where the decision to wear a cap and gown or an armband is suddenly politically significant, the educational achievements of valedictorians may not particularly qualify them to comment on the times. Yet any apolitical farewell address delivered on this occasion would be a peculiar anachronism.

The first five months of this decade have intensified the frustration which characterized most of the 1960s. The past decade began with the hope of racial equality, of prosperity for all, of peace. It began with the exhortation of a youthful, vibrant John F. Kennedy: “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” This new decade begins with the knowledge that Fred Hampton and Mark Clark did not fire on the police whose gunfire killed them in Chicago, and that their fellow Black Panthers, skeptical of the legal machinery, are unwilling to assist it in achieving justice. It begins with an unsteady economy in which inflation affects everyone and unemployment threatens the lower income brackets. It begins with the longest, costliest war in our history still in progress, despite the desire of everyone for disengagement in some form.

It begins with many of our best educational institutions on “strike,” whether from conscience, fear, or violence, and many buildings on fire. It begins without John F. Kennedy, or his brother, or Medgar Evers, or Martin Luther King, or thousands of young Americans, Vietnamese, Arabs, or Israelis. Finally, it begins with many holding conflicting ideas of what they and everyone else should do for their country and little tolerance or understanding for any other viewpoint.

America as a whole, and my generation in particular, had rising expectations which have not been satisfied. There has been frustration; to a large degree, this has produced the many demonstrations, much disruption, and considerable violence of the past decade. As a result, to justify every disorder, whatever its nature or consequences, by its cause is one popular approach. On the other hand, the reaction to disorder has given support to those who would condemn and suppress it in the name of law and order without even considering its origins. It seems that more and more persons feel compelled to choose one of these two stances. In good conscience, I can accept neither, and pray that others also will not. To do so is to contribute to the deepening division in this country, to line up on one side in the confrontation of young versus old, black versus white, North versus South, the radical versus the system. To do so is to be true neither to the American flag and the country it represents nor to the peace symbol and the concept it depicts.

We all wish an end to both frustration and violence, an end to racism, poverty, war, and pollution. To enlist the support of the many persons in this country who share these concerns, they must be communicated rationally and constructively to the world beyond. It is clear that this often has not been done. The Vietcong flags, obscenities, and violence of a few have made headlines and alienated many. They have generated overwhelming emotional reactions in the general public which have negated any rational consideration of the serious issues of our time. Fear and distrust of the young, the long-haired, and the black have often been reflected at the polls. In 1968, the presidential campaign was heavily flavored by the issue of law and order, and nearly 10 million votes were recorded for George Wallace. In 1969, 58 percent of the voters in New York City supported two basically law-and-order mayoral candidates in the supposedly liberal Northeast. In 1969 in New Jersey and in Ohio, and recently in Oregon, clear majorities voted against suffrage for young voters.

All too often the issue in the minds of many has become whether they are for order, traditional values, and the government or for anarchy, communism, and SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. The deep concerns and serious moral stands of large numbers of students have often been obscured and their political effect nearly negated. Already inadequate lines of communication have been steadily weakened on the one hand by each new disruption and, on the other, by each new speech by the vice president.

These lines must be re-established. The recent involvement of many persons on this campus in the electoral process, as exemplified by the Movement for a New Congress and the modification of next fall’s academic calendar [to allow students to become involved in fall elections], cannot help but do so. Indeed, the personal exchange of ideas through canvassing may in the long term be more significant than the successful election of candidates. Such constructive efforts must become the rule, rather than the exception, not only for electoral movements, but also for individuals within their own families and communities, not only between voters and canvassers, but also between parents and their children, between alumni and students, and between academics and nonacademics.

Many will be neither dedicated nor energetic enough for the task at hand. It is neither quick nor easy, for years of neglect have taken their toll on both sides. Unfortunately, it will be much more convenient to be self-righteous, rather than understanding; to engage in rhetoric, rather than dialogue; to recognize the differences among men, rather than the common characteristics which unite all men as brothers. Moreover, the pace of progress will never match the immediacy of the problems.

But the campaign must be begun, not in the name of America or of peace, but in the name of, and for the sake of, both. To offer assurance of success would be to ignore the events of the past decade. But these same events should provide more than sufficient motivation, for the consequences of either inaction or radicalism are both obvious and ominous.

Thank you very much.

No responses yet