John Matthew Emery III ’79

(Following is an expanded version of the memorial published in the print edition of PAW.)

Jake died Dec. 7, 2008, at his home in Modesto, Calif., where he had practiced neurosurgery. Jake’s death was unexpected and a shock to his friends and family. He was healthy, but contended with “juvenile” diabetes that he contracted late in his neurosurgery residency training. Diabetes was a factor in his death. He died of a heart attack in his sleep after a dinner with friends. Jake was 51.

Jake had an adoring circle of friends across the country and his home was a focal point for fun and intellectually stimulating dinners and reunions. He had an incisive wit, spoke Spanish, French, and German, and could discourse eloquently on almost any topic from brain surgery to the appeal of reality television.

Jake came to Princeton from Philips Exeter Academy. After earning his degree in psychology, he took premed courses at Bryn Mawr College’s “post-bac” program before entering Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where he later received his medical degree. Jake was an intern and resident at New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center Department of Neurosurgery, and was junior assistant attending physician at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York from 1986 to 1992. He left New York to practice neurosurgery at Doctors Medical Center and Stanislaus Surgery Center in Modesto. Jake also taught clinical classes in neurosurgery at the School of Medicine of the University of California, San Francisco.

He was a very early adopter of medical office technology: Even in the early 1990s, he kept electronic patient files that incorporated video to improve assessment and document changes in patients’ health.

Jake also was committed to improving the organ-donation system for transplantation. He found it tragic that potential organ recipients died because potential donors (or their families) were not aware they could help or were frightened by procedures they did not understand. To help raise awareness, protect potential donors and their families, and improve the efficiency of the organ-donor system, he served on the boards of the New York Regional Transplant Program and the California Transplant Donor Network.

Jake was passionate not only about his proficiency in neurosurgical technique, he was passionate about — and compassionate in — providing patients the best possible medical care. He was unusually reluctant to recommend surgery, operating only when that was quite likely to improve the patient’s quality of life by enough, and for long enough, to be worth the risks. In the tradition of physician-scientists, he was a pioneer in the application of a surgical cure for hypertension (through a cranial-nerve decompression). A vocal critic of managed care, Jake declined to participate in the Medicare system, although he never turned patients away. He refused to accept payment from combat veterans, and his house was full of gifts from people whose lives he had improved — or saved. Before his residency, he served as a volunteer health-care worker in Africa.

An avid sportsman, Jake enjoyed golf and hunting, and won awards for trap and skeet shooting. He had an adoring circle of friends across the country and his home was a focal point for fun and intellectually stimulating dinners and reunions.

Jake is survived by his parents, John M. Emery ’53 and Patricia Monroe Emery; and his sister, Deborah “Debbie” Emery Maine ’83, her husband, John D. “Jordie” Maine ’83, and their children. We extend sincere condolences to them all.

Paw in print

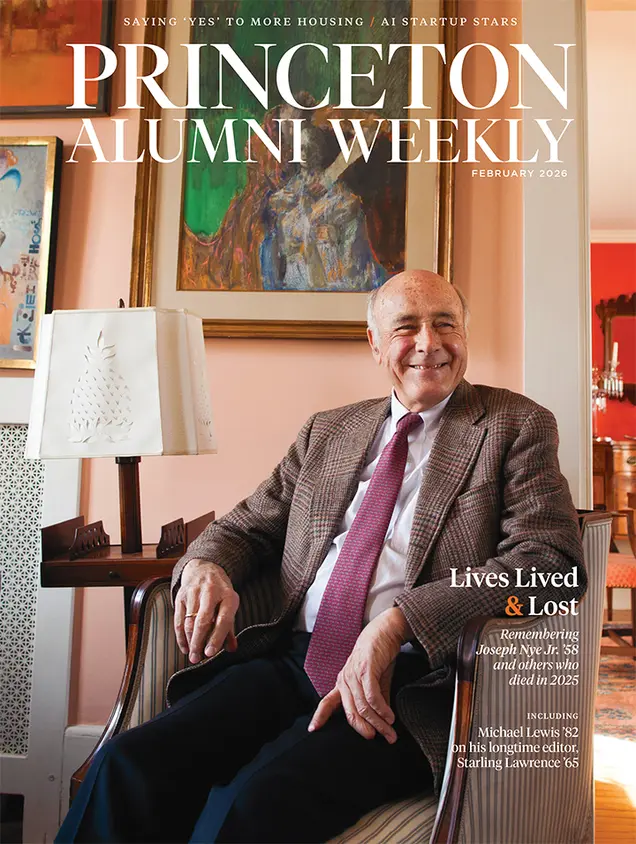

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet