Allan Roy Oseroff ’64

Allan Oseroff, who gained international renown as a researcher and clinician in dermatology, died of biliary cancer Oct. 16, 2008. He was 65 and had lived for many years in Buffalo, N.Y.

Allan’s years at Princeton were an academic tour de force. He won the Freshman English Prize and majored in English and electrical engineering before settling on physics. He then received doctoral degrees in applied physics at Harvard and in medicine at Yale.

Allan, who was chair of dermatology at the University of Buffalo and the Roswell Park Cancer Institute, was celebrated as a pioneer in the photodynamic treatment of skin cancer. And he was forever the physicist; before his death he was investigating the use of nanoparticles in the treatment of cancer. Allan also distinguished himself as a sensitive practitioner beloved by his patients. When the Castellani Family Chair was established in Allan’s honor at Roswell Park, he was cited both for the compassion and the skill he brought to the treatment of the Castellanis’ daughter, a victim of adolescent cancer who became close to Allan’s family.

Allan’s classmates extend their deepest sympathies to his wife, Stephanie Pincus; his children, Matthew, Tamara, and Ben ’11; and two grandchildren.

Paw in print

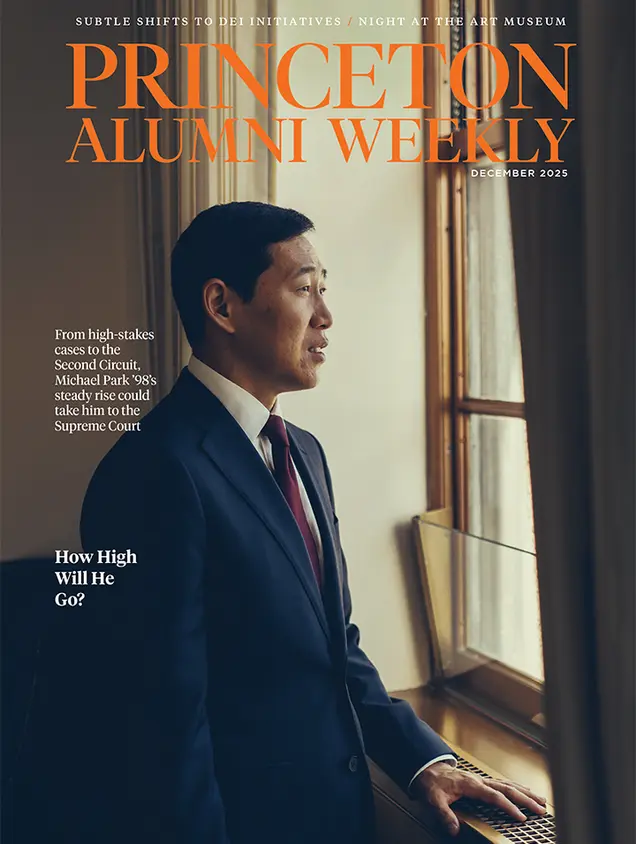

December 2025

Judge Michael Park ’98; shifts in DEI initiatives; a night at the new art museum.

No responses yet