Frank L. Helme ’54

Frank Helme died peacefully Sept. 22, 2012, after a long siege with Alzheimer’s.

Born in Port Jefferson, N.Y., he majored in mechanical engineering at Princeton. He was a member of Cloister Inn and active in crew and the rifle team. Frank graduated with honors and then volunteered for active duty in the Army. He became responsible for a radar installation and worked with a team to train its operators. He fulfilled a 10-year commitment in the Army Reserve and was discharged in 1963. He earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from RPI in 1960. He then completed his training at the KAPL Nuclear Power Engineering School and became a plant-shutdown director. Frank worked in that capacity until his retirement in 1994.

In his retirement, he became an expert in producing glazed pots, boating, and travel. Throughout his life, he was a spiritual questioner and seeker.

Frank is survived by his wife, Ruth Bonn; his son from a previous marriage; and two grandchildren. The class extends sympathy to them on their loss and gratitude for his long service to our country.

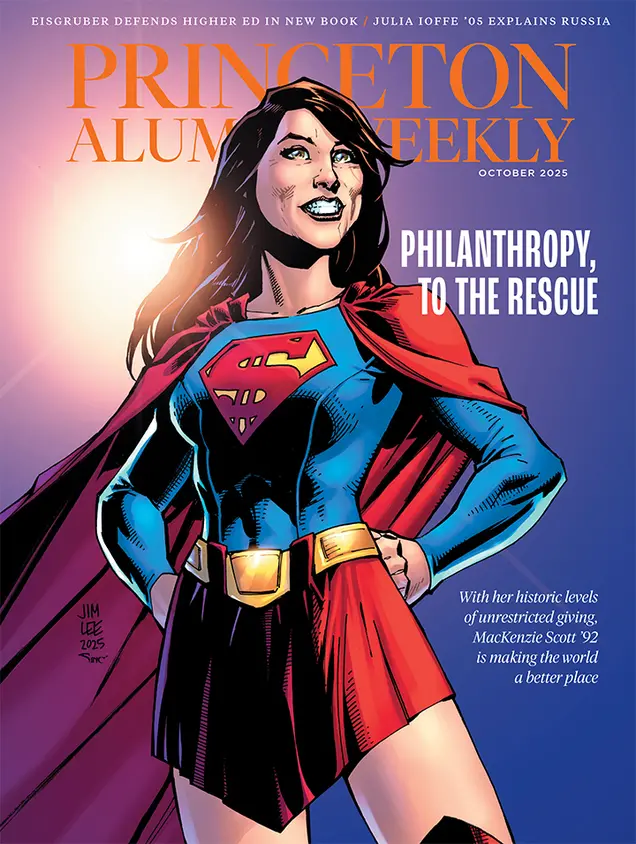

Paw in print

October 2025

Philanthropist MacKenzie Scott ’92; President Eisgruber ’83 defends higher ed; Julia Ioffe ’05 explains Russia.

No responses yet