Robert Karl Heimann ’48

BOB HEIMANN died on Feb. 18 at the age of 71. He was a bit older than most of us. This was an advantage in that he donned the mask of an elder statesman in his role as chairman of the PRINCE. His stately bearing was, however, quite unable to contain a flair for devilment and merry pranks. His intricate, ingenious verses in revising the Faculty Song sent some faculty up the wall, but mostly filled the air with mirth. Bob was the moving spirit of the Unofficial Register (catalog) of the University which drew blood in more pompous circles with satirical obser¬vations, and was a first in student's evaluating courses and professors. In a more reflective and benign mode, while contemplating the gentle loveliness of a May eve¬ning from the porch of Colonial, Bob had a vision of Prospect Ave. without cars or paving—just grass; this caper received University endorsement, but was blocked by town fathers and bureaucrats.

Bob's career in the business world was rather mete¬oric. After a stint as an editor at NATION'S HERITAGE and then at FORBES magazine, he joined American Tobacco Co. in 1954, rising to become president and CEO from 1977 to his retirement in 1980. In 1969, the company became American Brands. In 1964, Bob took the tobacco advertising from sports sponsorship "to avoid any ap¬pearance of appealing to young people."

To his daughter, Karla Brandt, and son, Mark '72, the Class extends deep sympathy and shares their loss.

The Class of 1948

Paw in print

December 2025

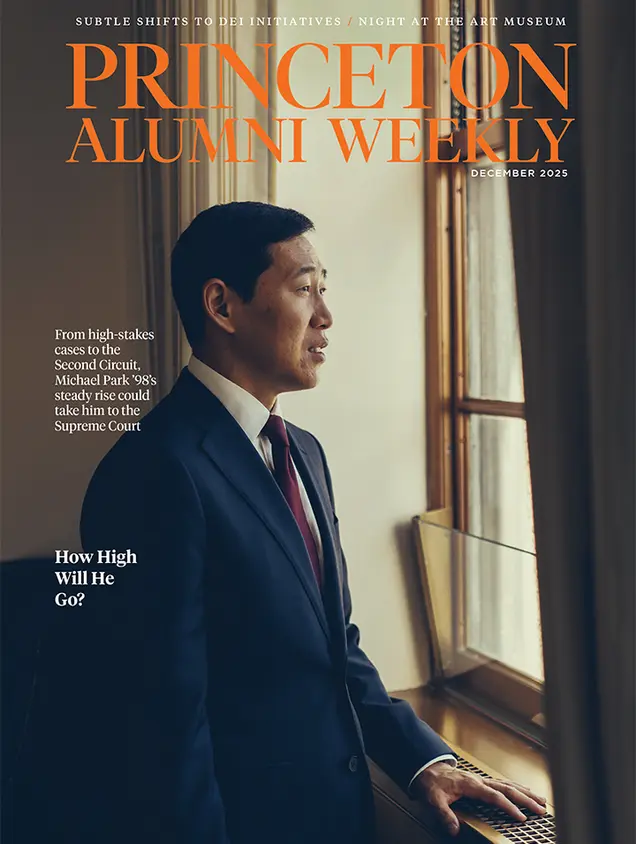

Judge Michael Park ’98; shifts in DEI initiatives; a night at the new art museum.

No responses yet