Carl Castle Fischer ’24

CARL FISCHER died on Dec. 23, 1989. He prepared at Franklin High School. After graduation he studied medicine at Hahnemann Medical College in Philadelphia and did post graduate work in St. Louis and New York.

He returned to Hahnemann in 1930 and remained on their staff until he retired in 1969. Throughout his career at Hahnemann he served with distinction as a physician-educator, researcher, and distinguished alumnus. He was chairman of their admissions committee and consultant of their children and youth program. In 1963 he was named their Alumnus of the Year.

In October, 1982, on his 80th birthday, he was honored with the dedication of the Carl C. Fischer, M.D. Memorial Intensive Care Unit at Hahnemann University Hospital.

He is survived by his wife, Mae; his daughter, Elaine Marshack; two sons, Charles and John '65, and five grandchildren. To them we extend our sympathy.

The Class of 1924

Paw in print

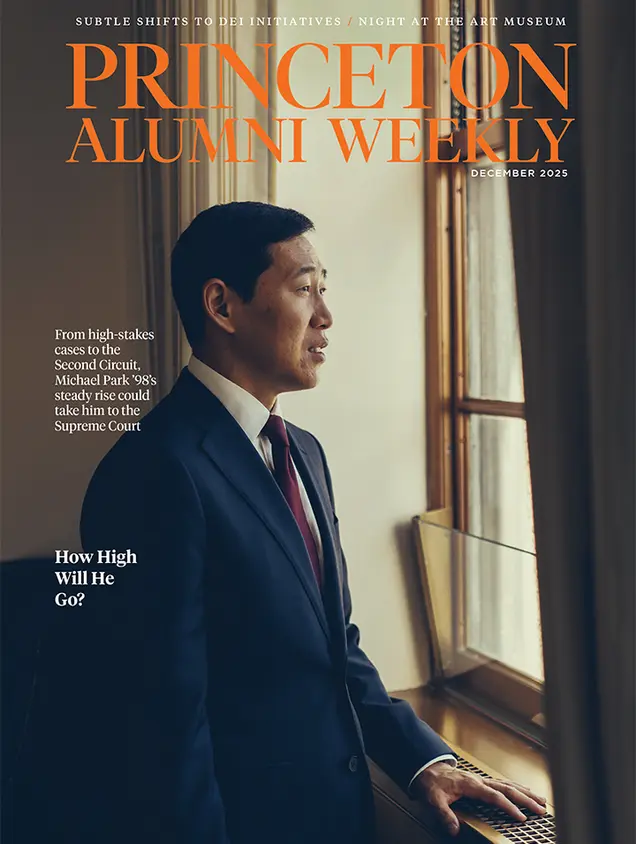

December 2025

Judge Michael Park ’98; shifts in DEI initiatives; a night at the new art museum.

No responses yet