William G. Reinecke *62

Bill died May 31, 2021, in Peabody, Mass.

Born July 21, 1935, in South Bend, Ind., Bill graduated from Purdue University and earned a Ph.D. in aeronautical engineering from Princeton in 1962.

After serving in the Air Force, Bill joined Avco Systems Division (subsequently Textron Defense Systems). As director of engineering, he was responsible for the development of three smart-weapon systems for the Department of Defense, including the sensor fused weapon BLU-108, which was successfully employed in the liberation of Iraq. He developed the first experimental facility to measure the erosion impact of rain and dust on high-speed projectiles, which has had a major impact on the design of U.S. reentry vehicles.

At the Institute for Advanced Technology at the University of Texas at Austin, Bill worked on the aerothermodynamics and impact of unconventional hypersonic projectiles, leading to the first aerodynamically stable, explosively forged penetrator (an anti-tank weapon).

He chaired two NATO industrial advisory groups, was national director for aerospace sciences of AIAA, and was a member of the international ballistics committee of the National Defense Industrial Association.

Bill is survived by his wife of 61 years, Sandra; daughters Sheryl and Kathryn; and four grandchildren.

Graduate memorials are prepared by the APGA.

Paw in print

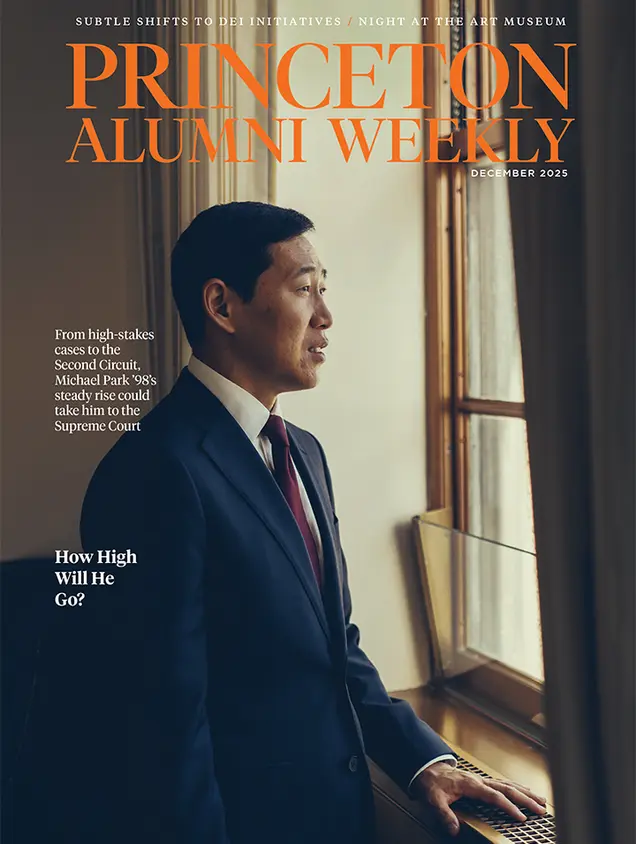

December 2025

Judge Michael Park ’98; shifts in DEI initiatives; a night at the new art museum.

No responses yet