Three scholars with Princeton graduate degrees are among 25 MacArthur fellows who will receive $500,000 “genius grants” over the next five years.

Two are on the M.I.T. faculty: John A. Ochsendorf *98, a structural engineer and architectural historian, and Marin Soljačić *00, a theoretical physicist. Biologist Susan E. Mango *90, a professor in the University of Utah’s department of oncological sciences, will join the Harvard faculty next July.

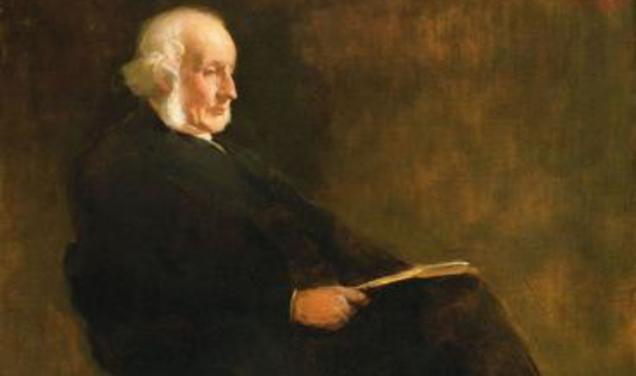

When he was notified of the award, “My whole body went numb,” Ochsendorf said. “I kept saying, ‘It’s not possible.’” Ochsendorf, who is 34, said he came to Princeton for a master’s degree in civil engineering to work with Professor David Billington ’50. “I can see Professor Billington’s influence in almost everything that I do, from teaching, to research, to the design of new structures,” he said.

Soljačić, also 34, has worked on several aspects of electromagnetic waves, including wireless power transfer and a switch in an optical computer. He praised Princeton for giving him freedom during his doctoral work to explore ideas “even when they were quite far from the mainstream.”

0 Responses