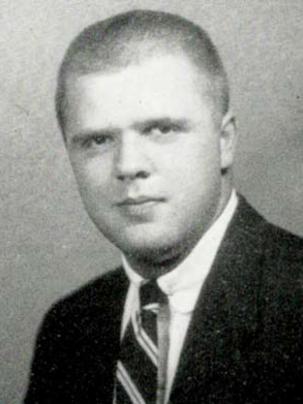

Edwin Milton Halkyard Jr. ’56

Ted died in Charleston, S.C., Jan. 3, 2025.

He came to Princeton from Bayside High School in New York City, joined Key and Seal, played interclub sports, majored in economics, and worked for The Daily Princetonian. Following time in the Army, Ted pursued a career in human resource management, attended the Harvard Advanced Management Program, and was named senior vice president of Allied Signal Corp.

Retiring at 56, Ted pursued a second career as a distinguished lecturer at the University of South Carolina business school. This and his wife’s enjoyment of the area led to a move to Charleston’s Isle of Palms, where their love for music led to service on the boards of the South Carolina Philharmonic and the Charleston Symphony, for which Ted served as president for three years. Many other organizations benefited from Ted’s interests, including Grace Church Cathedral and the Charleston Educational Network.

Ted married Joan Sherman from Skidmore right after graduation and together they raised a family of four sons while visiting more than 100 countries, including all seven continents twice! Joan survives him, as well as their sons Edwin III and his wife Karen, Martin and his wife Beth, Christopher and his wife Nicole, and Jonathan and his wife Kari; 13 grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren.

Paw in print

December 2025

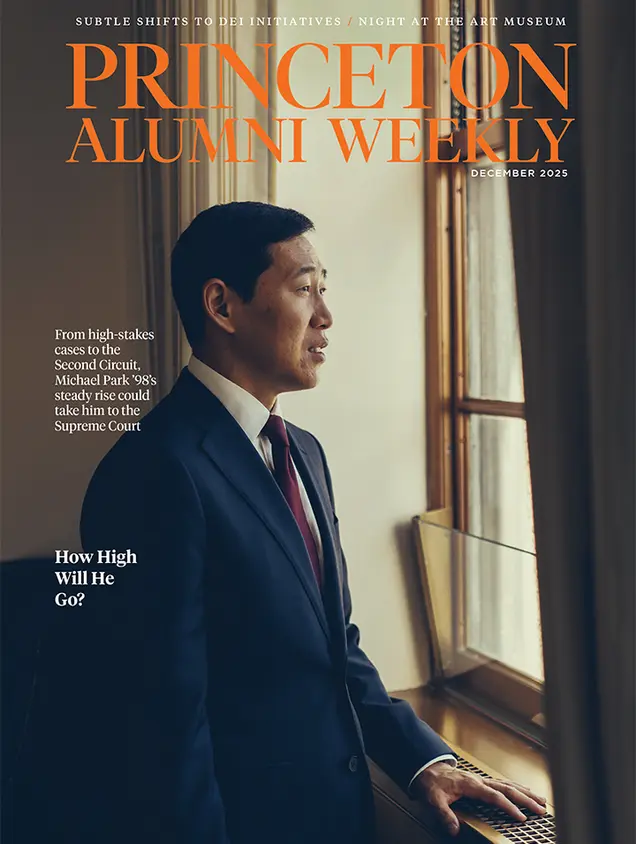

Judge Michael Park ’98; shifts in DEI initiatives; a night at the new art museum.

No responses yet