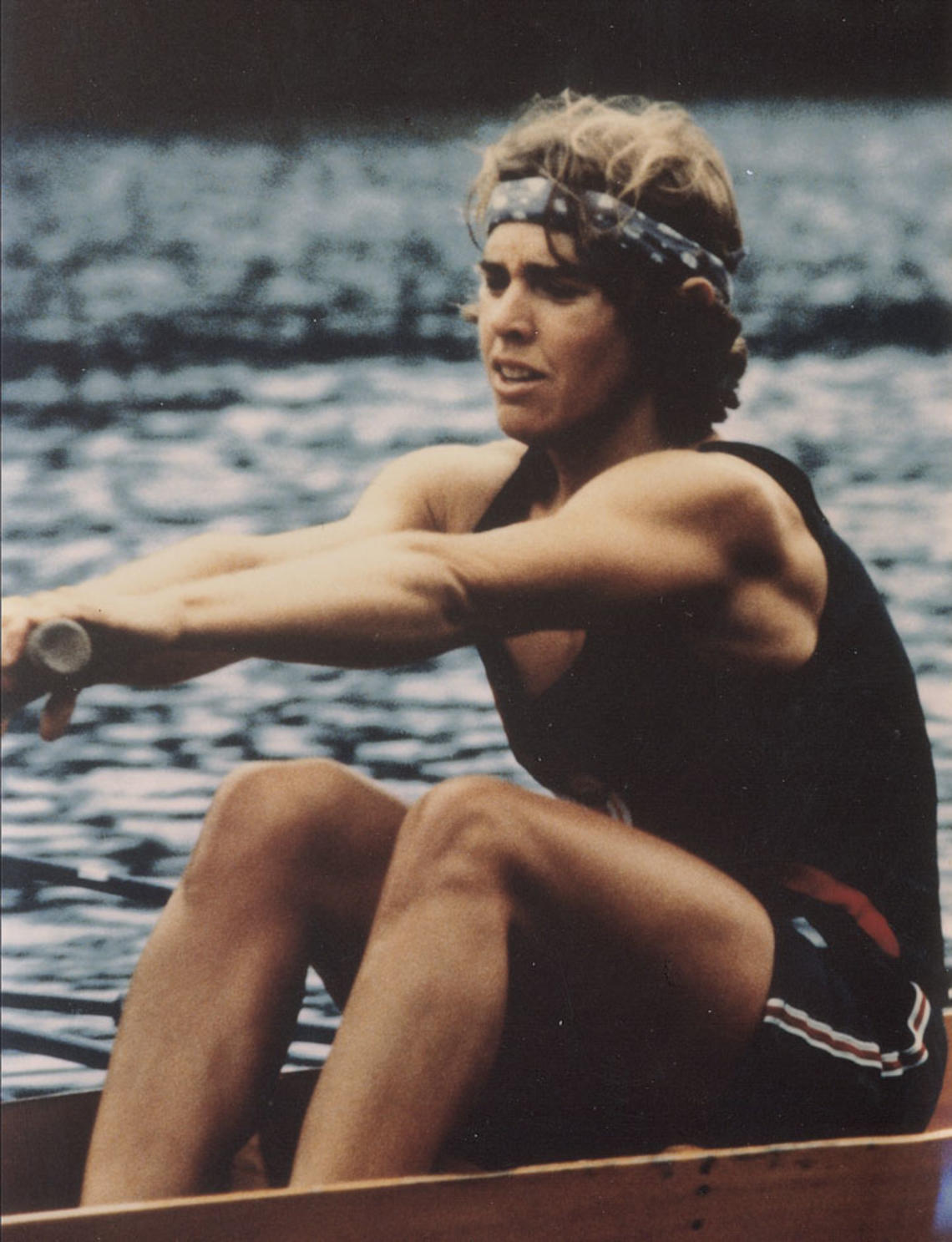

In the early 1970s, the women’s rowing team was easy to spot in campus dining halls. “We didn’t have time to change [after practice],” Carol Brown ’75 recalled, “so we’d come up from the boathouse wet and dripping, cold and sweaty.” The experiences with her teammates built lifelong bonds, and Brown’s training on the water led her to a milestone medal at the 1976 Olympics.

PAW Tracks is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

For the record

The audio misidenitifies Brown’s medal at the 1976 Olympics. The U.S. women’s eight won bronze in Montreal; Brown won silver a year earlier at the World Championships.

TRANSCRIPT:

Princeton’s winning tradition in women’s sports dates back to the earliest days of coeducation. Some of the pioneering women in those early classes came to college with impressive athletic résumés. But for three-sport athlete Carol Brown ’75, it was all new.

Brown: I was not an athlete before I came to Princeton. I went to high school in Illinois. There was a state law in Illinois that there were no girls’ sports in the public schools. It wasn’t just that there weren’t many or it wasn’t supported, there was a state law that there couldn’t be. So I’d done nothing. I was a musician. I played in the band, the orchestra, sang. That’s what I did with my energy and my time. I’d swum on local summer swim club teams. That was it.

I came here and it’s like, “Well, what’s new and different and something to try.” There were only three women’s sports – field hockey, tennis, and crew – and the field hockey and tennis players had all been nationally recruited. Nobody had ever rowed before so there were signs up to come try it. I found my way to the boathouse and rowed all four years and rowed for almost 10 years after I graduated, and multiple Olympic teams. So that shaped my whole experience here, and I didn’t have any expectations.

The woman who started it was an upperclass transfer from Smith. She hadn’t been an athlete before but she tried rowing at Smith and loved it. She transferred here as a junior. She was a classics major. She’s now a professor in California. She’s more like coxswain size than a rower size, but she loved the sport and she had already started beating her way into the boathouse when the rest of us arrived and sort of gave some support. So none of us had been serious athletes. None of us knew what we were getting into. It was just outside. It was different.

You immediately had this bonding just because of the challenges and because we weren’t allowed in the boathouse when the men were around. Immediately yes, you’re invited to join the crew team, but no, you’re not allowed to use the bathroom at the boathouse. You’re not allowed to be seen when the men are around. You can only row from five to seven in the morning. The coach is a volunteer. We’d have bake sales to buy him a raincoat and a megaphone because the University didn’t even provide that. So I think it attracted this group of us that loved doing something new, knew we were blazing ground. The team had this incredible sense of team that you get from any of the sports, but we were special because of all the trials and tribulations.

I didn’t have to fight as hard, but I pushed and started the women’s swim team and was captain of the swim team for three years. I actually then played ice hockey my senior year, so I did three. And I sang in the glee club. And I did graduate and go to class.

Princeton missed the boat on being prepared for the female athletes. They did such a fabulous job on the academic field and the faculty were ready to embrace us. But they hadn’t done their homework or weren’t willing to take on the entrenched men’s coaches, where adding the women meant we were encroaching on their territory or their time or their resources. It was a completely different experience being one of the first female athletes versus being a female student.

They should’ve seen this because the kind of women who were going to come wanted access and deserved access to everything. Not, “Oh, we’re going to let you into Princeton and you get access to all the great faculty and academics now, and then you’re going to gradually get access.” No, we want the whole menu and we want it now, and we got it.

We were sort of labeled. The battles that we had at the boathouse were fairly visible on campus, particularly among all the other women even if they weren’t rowing. The women’s athletics grew so quickly, and the women athletes were sort of a cohort. Most of the men were supportive of us, so the battle was not like the alums that were writing in to the PAW every week saying, “There are women in my dorm and women here and it’s ruining the University.” The men on campus for the most part were supportive of us being athletes. But the rowing schedule and limitations and everything meant we were always the last in the dining hall. We didn’t have time to change, so we’d come up from the boathouse wet and dripping cold and sweaty in our sweats and sit in a corner of the dining hall. So we were very obvious. People knew, “That’s the rowers.” Quite a few of the women on the rowing team were also battling for and started the women’s basketball team, but they weren’t allowed to play in Jadwin because there weren’t any bathrooms they could use in Jadwin. And a couple of them wanted to play lightweight football. We were all definitely a cohort of active women that wanted to be athletes here and certainly identified with being the pioneers in the athletic arena.

Summer after junior year, I made the national team with a woman from Princeton. We raced in the nationals in a pair, a totally unexpected success. I had a job leading bike trips in Switzerland, and even after we won the nationals, which put us on the national team to go to Europe and race in the World Championships, I tried to not go and to let them take someone else to go with Janet and row. That’s how — I still didn’t have a perspective on what this meant, and even then I really wasn’t thinking about trying out for the Olympics even though 1976, a year after I graduated, was the first time women’s rowing was on the Olympic program. I hadn’t really thought, “Who’s going to make that team? There not women who have been rowing for 10 years and five years out of college (like there are now) – it’s going to be us.”

Brown made the U.S. team for the 1976 Montreal Olympics, and then she made history, becoming the first Princeton woman to earn a medal – a bronze in the women’s eight.

I still race once a year at the Head of the Charles with national teammates in the old ladies’ boat. We still can get in the boat and row three miles and do well and get back out. Fortunately the boats have gotten lighter. They’re not the big heavy water-soaked wooden boats that we had. So as we’ve aged the equipment’s aged with us.

Our thanks to Carol Brown for sharing her story. Brett Tomlinson produced this episode. The music is licensed from FirstCom Music.

We’ll be recording oral history interviews with alumni at Reunions in May. If you have a story to share, send an email to paw@princeton.edu.

Paw in print

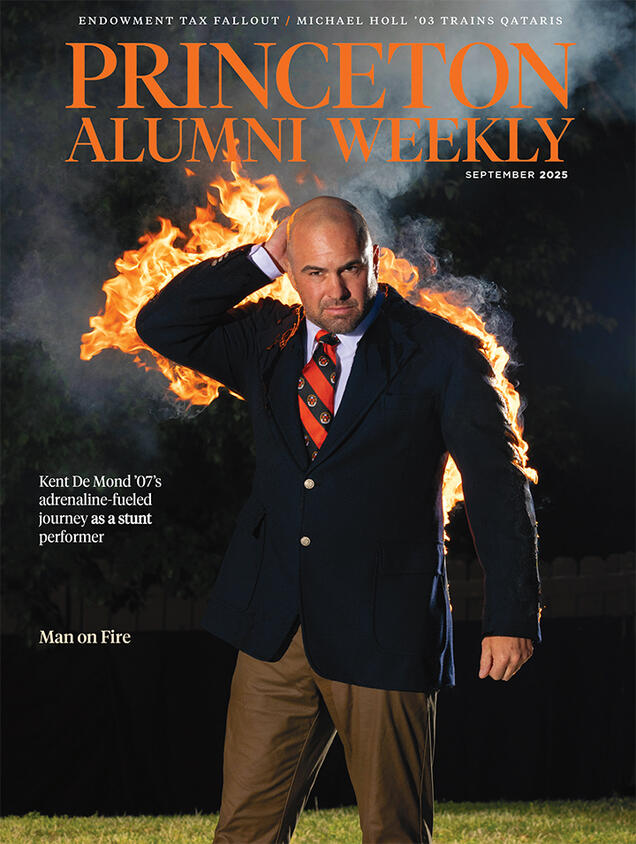

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

No responses yet