PAWcast: Jon Ort ’21 on Firestone’s Forced Labor and Donations to Princeton

‘Liberian labor, coerced Liberian labor and the exploitation of Liberia, underpinned the library’

Firestone library has a story behind it: In the years before it was built, Princeton leaders realized a world-class research library was needed to stay competitive with the nation’s other top universities. Firestone’s million donation made it happen, but where did the money come from? Jonathan Ort ’21, now a graduate student at Yale Divinity School, recently published a piece in the Princeton & Slavery Project about the massive Firestone rubber plantation in Liberia that used a racist system of forced labor beginning in the 1920s. Ort paired this history with records of donations the family and company made to Princeton, and on the PAWcast, he spoke about what he found — and what understanding readers might take away.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

Liz Daugherty: While he was a history student at Princeton, and editor of The Daily Princetonian, Jonathan Ort, Class of 2021, began researching the Firestone company. Yes, that Firestone; the one that once dominated the rubber and tire industry and the one that donated the $1 million to build Princeton’s world-class library in 1944. What he found was recently published in the Princeton & Slavery Project, which investigates Princeton’s historical involvement with slavery. This time, the forced labor wasn’t in America but Liberia where Firestone used a racist system of forced labor to run its massive rubber plantation. Ort spoke with PAW about the connections he found between this system of modern day-slavery and the Firestone family’s many donations to Princeton over five decades.

So Jonathan, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me today.

Jonathan Ort: Liz, thank you so much for having me, and to PAW as well.

LD: So let’s start with you. How did you come to work on this topic and the articles you’ve written?

JO: Yes, thank you so much for that question. When I first arrived at Princeton in the fall of 2017, Princeton was only a few years out from the Black Justice League protests which forced the University to have an honest reckoning with the legacy and the idealization of Woodrow Wilson on campus. And so I feel that in terms of my own consciousness about Firestone, I’m very much indebted to the work of the Black Justice League, in terms of fostering critical recognition and critical examination of how campus is constructed, and the kinds of names and legacies that we commemorate in terms of our iconography.

And so that was in the back of my mind. While I was in high school, I happened to read a book that mentioned the Firestone plantation in Liberia, and then arriving on campus and seeing the Firestone Library, I wondered if there was a connection there. So it really was sort of tangential or just by chance that I happened to put two and two together. And as I began to look more into the fact that this was the Firestone company, which for nearly a century has exploited Liberia, and as you said, in your introduction, created a racist system of forced labor and really an enclave of white supremacy in Liberia.

I put those things together, and I realized that there was some sort of connection here and there was a story to be told. And I first, I first called for the University to examine and disclose its ties to Firestone in an op-ed published in my first semester, and really there I didn’t know what existed. I went briefly into the University’s archives, and I just happened to look at a handful of the records between the Firestone family and Princeton University. So I had a sense that there was a lot there, but I hadn’t yet done the kind of thorough-going historical investigation, which is what the piece we’re talking about now is.

LD: You mentioned a book earlier that you had seen some of this research in, there was a more recent one as well. Can you tell me anything about that? Gregg Mitman, he’s a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, right? He wrote a book that was published last year called Empire of Rubber. Did that play into your, like, did you know about what he was doing? Or did it just kind of show up while you were working on this?

JO: You’re absolutely right, Liz. Gregg Mitman’s Empire of Rubber is a really important book. It’s a really important intervention when it comes to critically examining Firestone’s legacy as well as Firestone’s ongoing presence in Liberia. The book, as you said, came out in the fall of 2021, and upon its release, the Princeton Humanities Council sponsored a conversation between Gregg Mitman and Professor Simon Gikandi, chair of the English Department, which I listened to virtually, that’s how I learned about the book. So I saw the notice about the event that was happening at Princeton. And at that point, I was already well into my research looking at Firestone and Princeton.

So I didn’t know about Gregg Mitman, Professor Mitman’s work until his book was published. That being said, I had the chance to get a copy from Labyrinth, which was carrying a copy because of that event that Princeton hosted. I read it in the first couple of months of its publication. And I have to say that it’s been really formative to me. As far as I know, it’s the first book-length treatment published in United States that examined Firestone’s abuses in Liberia and I think the insights are really, really vital. I had the chance to talk with Professor Mitman as I was researching the piece, and so you’re absolutely right that his work has very much informed me. It’s probably more often cited in the essay than any other source.

LD: Was what you were researching here with Firestone a little unusual for the Princeton & Slavery Project? I think, and correct me if I’m wrong, a lot of it has centered on the slavery that Princeton itself participated in, whereas here we’re talking about the University benefitting financially from a company.

JO: I think you’re spot on, Liz. This piece differs from a lot of previous work, a lot of previous excellent work done by the Princeton & Slavery Project in two ways. I would say the first, you’re right, is that my piece concerns financial entanglements, primarily arising from donations that members of the Firestone family, as well as the Firestone company made to Princeton. And so there is a particular way in which those complicities in racial exploitation and white supremacy manifest. I think the other significant difference is that this story unfolds across the 20th century into the 21st, right? I think it’s always important in this topic, and I find myself, it’s important to remind myself that Firestone’s plantation continues today. And there are many troubling structural continuities from the past.

But this is also a story about the 20th century. And as I say in my piece, this is a story about how the forces of racial capitalism and white supremacy profited Princeton, and transformed the University into what we know it to be today in the century after abolition. The Princeton & Slavery Project really has so many dozens and dozens, if not hundreds of pieces, examining Princeton’s entanglements with the U.S. institution of chattel slavery. And the Firestone plantation is a different form of structural anti-Blackness, but we see, once again, continuities. And so I’ve had a lot of conversations with the editor of the project who has her Ph.D. in history from Princeton; that’s Isabella Morales and Dr. Morales and I talked a lot about how this piece might also orient us to a critical consideration of the University’s entanglements in racism and anti-Blackness in the 20th century right into this present day.

And so, you know, I think that we wanted to be very clear in terms of saying we’re not talking about slavery in the United States before the Civil War. But we are talking about a history that unfolds in the aftermath of those events.

LD: So tell me about Firestone’s operation in Liberia. How did it begin and who were the workers?

JO: The story of Firestone, Princeton, and Liberia begins in 1926 which is the year that Harvey Firestone, Sr. who is the namesake of our library, gained a massive concession to operate a rubber plantation in Liberia. So Harvey Firestone, who is this rubber magnate, founder of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, gains, wrests from the Liberian government, this lease, over a million acres, a huge swath of land roughly 10% of Liberia’s arable territory. And he has basically has 100 years, a promise to have carte blanche to cultivate rubber trees on this tract of land for 100 years. And this disagreement isn’t a fair deal between Liberia and Firestone. It’s achieved through the manipulation of the U.S. State Department, which wants to see the U.S. rubber industry become ascendant in the global market and usurp British and Dutch rubber manufacturers who at that point really dominated the market because of their colonial possession.

So what we see once again is that the U.S. State Department colludes with Firestone to gain terms that almost guarantee that Liberia will be exploited. And so 1926, in the years that follow, Firestone establishes the plantation through massive acts of destruction and violence, which includes displacing Indigenous Bassa communities who live in the land that’s now designated for the plantation. And so the forest that grows there is razed and rubber trees, millions and millions of rubber trees are planted in their place.

Liz, you asked about who is working at the plantation, which is such an important question. And that’s really where one of the first Firestone atrocities arises. Firestone was depending on and presumed that it could obtain a workforce of hundreds of thousands of laborers, Liberian laborers. And the fact of the matter is that Firestone could never achieve a workforce of that size through purely voluntary means, just looking at Liberia’s population, the distribution of where people lived. It’s quite clear from the estimates and the presumptions that Firestone was making, that it was going to need to coerce laborers into working at the plantation.

And what we see is that in some ways, Firestone creates a system of plausible deniability, in which the Liberian government — which is hoping that Firestone will help to develop the country — the Liberian government will go to various parts of the country and bring in dozens, if not hundreds, of laborers who are forcibly removed from their home communities, and forced to arrive at the plantation and to work. There’s actually a quota system, where people from different parts, different villages are being funneled into the plantation, and then working against their will.

Once again, it’s Firestone itself is not going to these places, and removing the workers, it’s doing so in collaboration with the Liberian government. And that means that by the time a few years later that this entire scheme has come under massive scrutiny, the League of Nations opens an investigation into allegations that Liberia is practicing slavery. But that investigation itself is designed in order to help Firestone at Liberia’s expense and so that that investigation finds that Firestone isn’t guilty of any wrongdoing at all, but it does implicate Liberia in this forced labor scheme, which is just to say once again, that the laborers are coming from all parts of Liberia. They did not necessarily agree to come to the plantation, there are of course coming under coercive circumstances. There’s records of dozens of laborers dying in their first weeks of arrival. And then once they arrive at the plantation, they are entirely under the company’s control. And that’s a dynamic that, in some ways continues to this day. They’re living in company towns within the plantation. The only place where they can purchase their food and medicine is from the company stores.

The Firestone company has long claimed that its subsidies for workers and its health care make its operation in Liberia progressive. In fact, I argue that it’s the opposite. Firestone, through its hospital system has long practiced segregation in the style of Jim Crow, has long practiced medical racism against its Black workers. And so I hope that gives you a sense of what the structural conditions on the plantation looked like from the beginning.

LD: Was Firestone the only company that was using forced labor like this in Liberia, or were there others?

JO: I think the Firestone arrangement is unique, particularly its presence as a U.S. corporation. There were, I think it’s worth noting, the 1920s, were sort of in the aftermath of the Berlin Conference and the scramble for Africa. And there’s, you know, colonial possessions all across the African continent, and particularly when it comes to rubber, rubber propels unconscionable atrocities inflicted upon African peoples across the continent. And I think we need to think no further than the Belgian Congo, for example. And in fact, thinking of another entanglement to a U.S. university, in the 1920s Harvard University had a medical expedition that both spent time at the Liberia plantation and the Congo.

And I know you asked specifically about Liberia, there were other forced labor systems. The League of Nations and its investigation considered allegations of forced labor, not only at Firestone, but in other contexts. One example is Ferdinand Po, which was an island off the coast of Liberia, and that also pertained to Spanish colonial interests. So I think that it’s important to acknowledge and to recognize the kind of historical moment we’re talking about, in which racism and exploitation propels the ways that the U.S. and Europe are draining material resources from Africa. And I think that’s absolutely true.

I think the Firestone example, I think Professor Mitman’s work attests to this fact. Firestone is, in a certain sense, a unique arrangement and one that reflects the projection of U.S. power. Once again, it’s the U.S. government helping Firestone to come into power here. And so I would say that it’s the sort of rise of a “modern” U.S. corporation. That’s what makes this particular example unique.

LD: So how did you research Firestone’s donations to Princeton and what did you find?

JO: The most important resource for my research has been the Mudd Library which holds the University’s archives. Mudd was closed, first for renovations, and then for COVID. And so that’s part of the reason why the research is coming out now — for a long time, it wasn’t possible to access those resources. But then in the fall of 2021, I had the chance to visit Mudd, and I want to recognize I’m really indebted, not only to the incredible archives there, but to the great librarians, the library staff who have been so helpful to the Princeton & Slavery Project from the beginning.

But to answer your question, Liz, for the Mudd Archives, you know, there’s an online directory and so I did a lot of work probing around and seeing what boxes and files had Firestone, or any connection to Firestone within the title. And so, what I did when I went to Mudd Library, I requested any box that I thought might have bearing on my topic, and those were, those were both, some of the boxes were explicitly marked as correspondence with the Firestone family or the Firestone Corporation. And then I was also drawing from the papers of three Princeton presidents who succeeded one another consecutively, and that’s Harold Dodds [*1914], followed by Robert Goheen [’40 *48], and then finally, William Bowen [*58]. And all three of these presidents, in their own ways, fostered close, warm friendships with the Firestone family, so I was also looking at the records from their offices.

In total I looked at about, I think it’s over 800 pages of material. And just to give you a sense of what some of that is, once again, it’s correspondence, it’s letters they’re exchanging, it’s records of stock, records of the shares of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company that were donated to Princeton. And then there’s also inventories of donations. There’s plans for how to build the library. You know, the range of material is really immense.

But I sifted through all of those pages. And as I told you before, I didn’t know what I would find. I had only been to the archives once before and looked at a small snapshot of this Princeton and Firestone story, saga really. So I didn’t know what I would find. But as I as I proceeded to, I should add too, I made no presumptions about what I would find, right? I think it was clear to all of us starting out this research that Princeton and Firestone clearly had entanglements and as you said in your introduction, Firestone Library attests to the scale of their ties. That being said, I didn’t know what would be there.

The story that emerged as I sifted through these 800 pages of documents is that Firestone transformed Princeton into one of the world’s foremost universities. And Firestone Library was a primary vehicle of how Princeton and Firestone helped one another. It’s not the only one, though. The Firestone family, more than 11 of whom attended Princeton, donated something like 150 times, more than 150 times, to Princeton over a 60-year span. So what I found, and I think what most surprised me and what I really wanted to emphasize in my piece, is that Princeton as we know it today wouldn’t have happened, wouldn’t have arisen without Firestone largesse. And we know then that Firestone underpins Princeton’s modern rise in the 20th century. And that being said, the kind of other crucial argument I’m making in the piece is that Firestone’s support of Princeton can’t be extricated from Liberia. And there’s some reasons behind that, which I’m happy to talk about, if it would be helpful.

LD: Sure. Well, I think that that would be great, because your piece of this whole discussion seems to be that connection. Like there has been, you know, Gregg Mitman’s, book and some research out there about Firestone and about Liberia. But you seem to be the one who put it together with Princeton, and tied those two pieces together. So yeah, can you talk about that a little bit more?

JO: Yes. Gregg Mitman in his book mentions, you know, Princeton only, actually, so Gregg Mitman talks about some U.S. universities in his book, Princeton is not really one of them. But I mentioned the Harvard Medical expedition. What Gregg Mitman says in the book is that Firestone turns to Ivy League institutions to advance and to help and to really profit the company, right. So when like, when Firestone is thinking about its plantation in Liberia, it’s turning to U.S. universities, particularly those that are the most prestigious and Princeton here comes to mind, right, in order to gain expertise, in order to gain legitimacy and credibility. And Harvey Firestone, I mentioned this earlier, Harvey Firestone, Sr. right, the namesake of our library. He’s the founder of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. He’s the one who brings the company into Liberia. His five sons all attended Princeton, and I think that’s a crucial fact for us to recognize because his sons who graduated throughout the 1920s into the 1930s would then run the company for the next half century. And in particular, his eldest son, Harvey Firestone, Jr. became both the most complicit in Firestone’s atrocities in Liberia, as well as the most involved and really the most, sort of most entangled with Princeton University.

So, I give this context in order to answer your question, Liz, about what are the entanglements that really implicate Princeton in Firestone’s exploitation of Liberia? First, I would say is that the people we’re talking about here, right, both the Princeton administrators, people like President Goheen, President Dodds, as well as Firestone’s leaders, and once again, Harvey Firestone, Jr. really comes to mind here. They themselves are wrapped up into this history that we’ve been talking about. Harvey Firestone, Jr., shortly after graduating from Princeton becomes head of the Firestone Plantations Company, which means that he directs the company’s Liberia plantation. And a few years after that, this is I think, about 15 years from his Princeton graduation, he ultimately become CEO of the entire Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, so he’s the one who manages not only the plantation but the company’s global operations. He also served as a Princeton trustee for 30 years. And I think one of the most striking findings from my research illustrates how Firestone and Princeton came together. And how Firestone gave money to Princeton, not just out of goodwill, not just out of a desire to help the University, but out of an intention, a strategic intention to use the University’s resources for its own benefit.

And so a section of my research, a section of the piece is called “Firestone Library: In the Service of Rubber.” What I found looking through these records from the 1930s, these letters that then-Princeton President Harold Dodds was exchanging with Harvey Firestone, Jr., they enjoyed a warm friendship, and they oftentimes consulted each other on various matters. And they were very clear in their letters in saying, you know, I’m asking you this question, but I’m shielding it from Princeton’s board. And we see that in the mid-’30s when Dodds first approaches the subject of a University library with Harvey Firestone, Jr.

Princeton had needed a larger and more state of the art library for close to 40 years. As early as the 1880s and ’90s we see records from Princeton’s administration indicating that Princeton desperately wanted and perhaps needed new library facilities, and decades later it had still failed to achieve that goal. And so, we see you can see in the record, this is what I found: Dodds approaches Harvey Jr. asking, broaching this possibility of Firestone’s support for a library, which ultimately results in the 1944 gift that builds Firestone Library. And I came across the founding memo for that library. This is a memo drafted by the board of directors of the Firestone company. And it makes quite clear that the company is donating to Princeton and is creating this library out of its own business interest. And it says more explicitly, that the library is to serve in helping the company and I believe that the quote is “maintaining its high position in the rubber industry.”

So this, so Firestone Library’s foundational, you know, founding memo makes clear the library’s purpose is to help the company remain in the top tier of the global rubber market. And this is an agreement that Princeton signed onto. We can see in the record that that Princeton agrees to the terms that Firestone laid out. And so what I really want to emphasize here, I’ve been talking to a lot of this kind of really minute history. I think the upshot for us today is that Firestone Library was conceived as a kind of corporate propaganda. Firestone Library was supposed to propagandize Harvey Firestone Sr. as well as the company that he had created. And so I think when we come to that realization, particularly that the company intended for its library, for our library, to serve and to propagandize the rubber industry, these really pressing entanglements with Liberia come into focus with more urgency.

When we realize that the library not only was created with money, with financial wealth that was exploited and that was drained from Liberia, but when we realize that Firestone Library itself is supposed to help into perpetuity, the cause of Firestone Plantation.

Just a couple of other notes about some of these entanglements. I want to be clear that Firestone’s plantation, you know, we talked about was Firestone alone in exploiting Liberia. What is clear is that Firestone’s plantation and the atrocities inflicted by Firestone were public knowledge from an early date. And so I think that’s also really important to recognize that it’s not as if Princeton can claim ignorance of Firestone’s record of white supremacy in Liberia.

As early as 1928 Raymond Leslie Buell, who was a historian, then at Harvard, but he had earned his master’s degree and Ph.D. from Princeton, he published a book in which he, in no uncertain terms, denounced the Firestone plantation, for its, for the conditions, which he said “made forced labor almost inevitable.” And that’s a quote. That same year, Marcus Garvey, the famous Black nationalist from Jamaica, had derided Firestone for treating its laborers and I quote, “as virtual slaves.” A few years later, W.E.B. Du Bois, who, one of the leading Black theorists, Pan-Africanists of the United States, he too, he had initially supported Firestone, thinking that it might help to develop Liberia but within five years, he had come to see the plantation for what it was and also condemned what was happening.

Those are just a few examples, but I think they attest to the fact that Princeton can’t claim not to have known because in U.S. public discourse, particularly from the circles of Black authors and theorists, Firestone, it was quite clear from early on what Firestone was doing.

The last thing I want to say is that it’s relatively rare, in fact, it’s quite rare in the record, the instances when Princeton acknowledges the Liberia plantation. But I think there’s one telling example, which is from 1970. It’s actually 1968 to 1970. In 1968, a Princeton administrator travels to Liberia, and is hosted at the seat of the Firestone plantation by one of Harvey Firestone Sr.’s sons. So once again, to be clear, that means a Princeton administrator traveled to the Firestone plantation and was hosted there for five days. And while they were there, the two men discussed the possibility that Firestone create a professorship of African Studies at Princeton. And I say in the piece that this idea is as obvious as it is out of place, right? The fact that Princeton is coming to Firestone, and really legitimating right, saying, well, Firestone you have this expertise about Africa, and we want you to help our nascent study in Africa, you know, of African studies, our really, our new program that we’ve just begun. And two years later Princeton openly makes the request that the two men discussed. And in that request, Princeton describes Firestone as having a long-standing and forward-looking interest in Liberia. That’s a quote, “that long-standing and forward-looking.”

And so I just want to be clear too that in 1970, which is about half a century into Firestone and Princeton’s relationship, we see Princeton doubling down on Firestone’s record in Liberia. So once again, the argument I’m making is that Princeton knowingly profits from Firestone’s racist system of forced labor, knowingly defends that system. And, once again, I think Firestone Library manifests those facts. But that was really rambling, Liz, so thank you for listening.

LD: No problem. What has the reaction been to your piece since it was published. And we should probably go back to your previous pieces as well. What kind of reaction have you had?

JO: I found that among people who are reading the work that I’ve written, there is definitely interest and a feeling that it’s really important and really urgent that Princeton faces its ties to Firestone, faces this history. But I think it’s also widely acknowledged that this history isn’t known. So I should actually say that, I think for a lot of people, a lot of Princetonians, a lot of people who have attended Princeton who might be on campus now, these kinds of findings may come as a surprise.

When I’ve spoken with people who do know about, you know, know a little bit about the Firestone history in Liberia, they tend like me to have come to it by chance where they happen to know there’s a Firestone company in Liberia, they happen to know that the library of Princeton is named for Firestone, and they put two and two together. But I would say that, you know, I’ve written about Firestone and Princeton for five years now, first with two op-eds, now with the actual historical investigation. People who read the work — faculty, students, alumni — I’ve received a lot of really affirming words and a lot of positive feedback. And I think there’s a sense among people who are reading this work, that the University needs to respond as an institution, needs to address these entanglements.

Liz, I think one example that’s somewhat interesting. In 2020 you may recall, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, Princeton faculty created a list of anti-racist demands that garnered some controversy and were the subject of a lot of discourse. One of the demands listed by the faculty in that 2020 letter pertained to Firestone. And actually in the same point, you know, first it said that Princeton should examine the presence of the statue of John Witherspoon in Firestone Plaza. And as I’m sure as you know that’s a subject of campus conversation right now, whether that statue of John Witherspoon, who enslaved people of African descent, deserves a spot on Princeton’s campus.

In the same kind of point though, the faculty also said and quoted from one of my op-eds there, that Princeton should investigate its ties to Firestone, and consider in some ways acknowledging its complicity in Firestone’s record in Liberia. And I think that’s an instructive point. I think it reveals where maybe a lot of the faculty are thinking that I think, recent conversations about what racial justice really requires, and demands have brought Firestone to the fore.

But I think this goes deeper than campus iconography too, and I think because of these kinds of structural entanglements. So the last thing I’ll just say is that the feedback has been positive. I’ve heard from a lot of students. In addition to the Princeton & Slavery piece, I published an op-ed in The Prince that was being circulated by students. I’ve heard from some Princeton faculty. I think, you know, one example that Kevin Kruse shared the piece on Twitter, and that garnered a lot of really compelling engagement.

But the last thing I’ll say, and this is what’s most important to me, is that I’ve heard from Liberian journalists and scholars as well. And the piece has been, as I understand, has reached an audience, particularly through Twitter, who are in Liberia, and that I’ve been able to talk with some Liberian Princeton alumni, as well as some Liberian journalists who are today reporting about Firestone, and they have received the piece and I think, would also agree about its importance. And so, to me, what’s most important now is what Princeton does to heed the voices of Liberians today.

LD: You know my last question was going to be about exactly what you just addressed which is how we should regard the Firestone name, given the reckoning that we’ve had in the last few years. But you’ve kind of already answered that. So is there anything else you’d like to say or anything else you’d like to include?

JO: Yeah, that’s, well I think that’s a really important last question, Liz, and I’ll just maybe rephrase it a little bit, which is just to say, I think this kind of research will naturally invite the question, “Should the Firestone Library be renamed?” Or, you know, what does the Firestone name mean on Princeton’s campus, should it be scrutinized? And I think those are important questions to be asking, particularly because as we discussed, Firestone Library serves to propagandize the Firestone Company. So I think that is an important question to be asking, what does the name mean? But once again, I think that this kind of conversation needs to go deeper than the presence of a simple name.

And I think it’s also worth noting, this is not the same, this is not exactly analogous to, for example, Woodrow Wilson, the presence of Woodrow Wilson’s name on campus. Whereas the School of Public and International Affairs had been formerly named for Wilson to honor him. This was a decision that Princeton had made, to honor him. Here we have the naming of Firestone Library as a result of financial gifts, and so that’s a different kind of arrangement and I actually think that it calls on the University to dig deeper. Because it’s not just that the library is honoring and centering the Firestone name, it’s that Liberian labor, coerced Liberian labor and the exploitation of Liberia, underpinned the library. So I really think that this kind of conversation, naming is one register in which this conversation can be had, but I think when we think about structural remedy and reparation, it needs to go deeper.

And what I owe to Gregg Mitman, when he came to Princeton to talk, what he said from the outset is that he feels as a white American scholar, the story he’s told is one of U.S. industry and how it exploited Liberia. He was very clear that he sees examining Firestone’s history but he’s not attempting to speak for Liberia. And I owe that insight to him and that’s how, that really has guided my research as a white Princeton student who’s told the history. I’m very cognizant of my own positionality and of what my work is to do. And so I feel that it’s quite important to acknowledge that the story I’ve told is one of Princeton and Firestone’s entanglement as they pertain to Liberia. But the story that is left to be told, the story that needs to be told today has to come from Liberians themselves.

So I think it’s really imperative for all of us a Princetonians, all of us as members of the Princeton community, to think about what does it mean to really heed what Liberian communities are saying today, and how can Liberian communities guide our response today? Because it’s Liberian voices that were suppressed by Firestone that are suppressed today and Princeton, really, Princeton was involved in the very founding of Liberia 200 years ago and that itself was another act of racial exploitation. So I really feel that’s the note I want to end on. That it’s imperative for all of us to heed what Liberian communities have to tell us.

LD: All right. And really quickly before we wrap up, I did want to say on the record here, prior to recording this podcast, PAW did ask the University’s communications department whether the University has any comment to make about Jon’s Firestone research and they declined to say anything.

So Jon, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today. This has been so interesting.

JO: Liz, thank you very much for having me. I’m so grateful for your interest and time.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

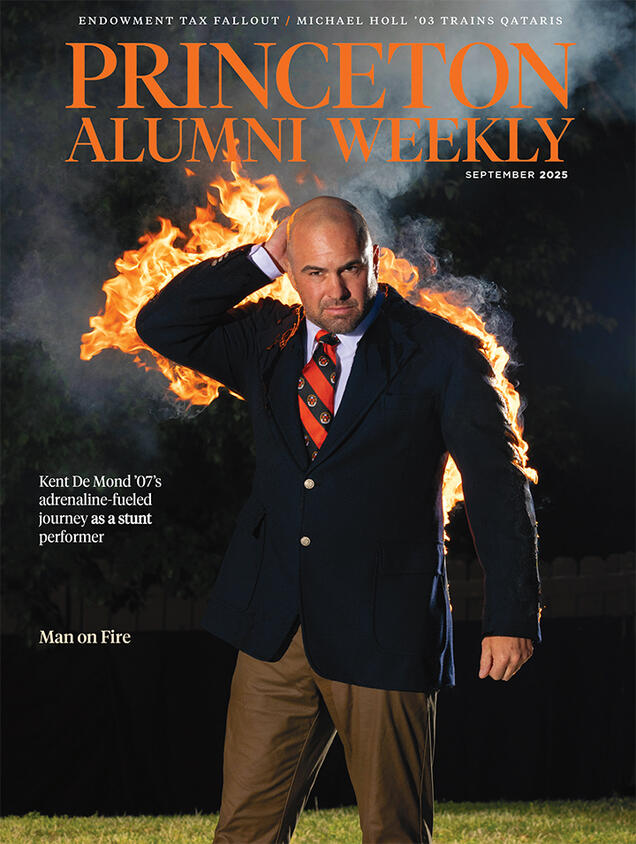

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

2 Responses

Jackie N. Sayegh

2 Months AgoA Hidden Secret Liberians Knew Well

Firestone had a practice of forced labor that filtered to every community close to its plantations. Local chiefs were forced by the Liberian government to provide young men for plantation work. The Liberian Labor Rights Forum v. Firestone Tire and Rubber Co. lawsuit is one of the ways child laborers fought back against the company. As a Liberian, I heard and saw the effect of the displacement of communities. Child Rights International Network highlighted the case of young Daniel Flomo, who began working at Firestone at the age of 7. President Tubman of Liberia was the largest owner of rubber farms outside of Firestone, so no help from the government on that end. I think this interview reflects the hidden secret of Firestone that we Liberians know so well, just like we know of the Fernando Po forced labor under then Liberian President King. Thank you, Jon.

Jay Tyson ’76

1 Year AgoA First-Hand Perspective of the Firestone Plantation in the Late 1970s

After graduating from Princeton in 1976 with a degree in civil engineering, I moved to Liberia to help with road construction projects as my main job, and to assist, in my spare time, with the development of our religious community there. I spend four years in the capital city of Monrovia, which was about an hour’s drive from the Firestone plantations. On some occasions, we went to visit members of our community in the outlying districts around Monrovia, including occasional visits to local members who lived next to, or within, the Firestone plantations.

I have never done any research into the history of Firestone in Liberia, so I claim no expertise in this area. I can only provide a snapshot of what I saw, while I was there in the late 1970s.

I can say that, at that time, I saw no evidence of any forced labor. I remember walking in the shade of rows and rows of rubber trees which had been tapped so that white latex sap of the trees dripped into small rubber cups. This liquid was periodically collected by local Liberian laborers. I never saw the inside of the plant to understand what conditions were like there, but I believe that most of the local labor was associated with the manual collection of the latex from the individual trees, rather than the processing of the latex inside the plant, which most likely was done with large scale machinery by relatively few workers.

I can say that I never saw any fencing that would have kept me out of, or kept workers in, the plantation. I never saw any guards to prevent people from leaving the plantation. (There may have been security guards around the offices and homes of the upper-level staff as a protection again thieves, but not for the purpose of preventing anyone from leaving the plantation.)

The houses that the Firestone company provided its workers were brick structures, which would have been considered rustic by Western standards. (As I recall, for instance, there were outdoor spigots for water, but no internal plumbing.) But to evaluate this properly, one would have to compare it to the alternative option of living in the villages, which normally had no plumbing whatsoever. There, water was carried in containers, often balanced on one’s head, from the nearest streams or, in some cases, from a well which the villagers had dug. Hot water was only obtained by heating it in a pan over a fire, and was seldom used except for cooking. (We lived in a comparatively modern home in the capital city, but even there, we lived without hot water for all four years. In a climate as warm as Liberia, where the cold water was never very cold, the absence of hot water was seldom a problem.)

The plantation houses were well-spaced, in an orderly layout, not as crowded together as was common in the Liberian-built capital city. But then, more space was available on the plantation.

I recall a conversation I had with one young man about why people would come to work here instead of remaining in their home villages. His answer was one that I had not considered: Life in the villages, which was typically supported by non-mechanized agriculture, was hard. And success often depended on the cooperation of the weather. Life on the plantation, with whatever drawbacks it may have had, was constant and did not depend on the weather. He, and the others I spoke to, were there by choice, not by coercion (unless one considers the weather as the agent of coercion).

I have to wonder whether Mr. Ort has ever been to the plantation in Liberia and lived there long enough to understand the conditions and options for its people. I wonder if he has ever lived in any of the Liberian villages (i.e. the non-plantation option). If he has not, I would highly recommend that he spend at least a couple of months there, and talk to a wide variety of people to understand their perspectives.

I was also rather surprised by Mr. Ort’s references to “white supremacy” in Liberia. Surely, he must know that the country was ruled by Americo-Liberians during the entire period from their settlement in the early 1800s until President Tolbert was killed by native Liberians in a coup d’etat in 1980. The Americo-Liberians were certainly not white. They were the descendants of the freed American slaves who decided to create their own country among the native Africans. They created a two-tiered society which was not entirely different from the two-tiered society they had left, except that both tiers, in this case, were black. While it is clear that the companies which later set up major businesses there were white-owned, they had to negotiate with the Americo-Liberian government for permission to operate. During my four years there, I rented a house from a native Liberian. As a white person, I was not allowed, by law, to own any real estate in the country.

All of this is to say that I think the situation there is a good deal more nuanced than what Mr. Ort seems to portray. I have no doubt that the Firestone Company made efforts to maximize its profits from its investments in Liberia. All companies do that. To judge whether that effort was taken to evil extremes would require an in-depth knowledge of the standards of the times, the other options available, and particularly an evaluation of whether the country would have been better off without the investment of the Firestones and other industries that went there. I’m not sure where such in-depth research would lead, but I suspect one would find a lot of self-interest on all sides, and blame that could be widely distributed.