Occupying Nassau Hall

Sit-in sparks campus, national debates; Eisgruber agrees to address demands

A student sit-in Nov. 18 ended after 33 hours, but the issues it raised — relating to Princeton’s racial climate, the role of history, and the legacy of a man long seen as a Princeton hero — remained after the protesters walked out of Nassau Hall.

Members of the Black Justice League (BJL), which also organized the Chapel protest last spring, left the office of President Eisgruber ’83 after a five-hour meeting in which the president agreed to address the group’s demands. He made no commitments about how the best-known of the demands — removing the name of Woodrow Wilson 1879 from University buildings and programs — would be resolved. The protest left the campus divided, with petitions springing up to oppose the demands and an unrelenting stream of articles and social-media posts published in both campus and national media.

In accordance with the agreement, meetings between top administrators and the student protesters have begun to take place. A Wilson Legacy Review Committee will post information and collect opinions from members of the University committee on its website, http://wilsonlegacy.princeton.edu. The 10-member trustee committee is chaired by Brent Henry ’69 and includes Ruth Simmons, former Princeton vice provost and Brown University president emerita, who led an exploration of Brown’s connections with slavery; and A. Scott Berg ’71, who wrote a best-selling biography of Wilson. Henry, now vice president at a Boston-area health-care system, led a sit-in in the New South administration building in 1969, when he was head of the Association of Black Collegians.

“I think what the students have done around Woodrow Wilson has been amazing, in terms of the conversation that it has sparked, not only here at Princeton but around the country,” said Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97, chair of the African American studies department. “I think that conversation can move in a number of different directions. As long as we are honestly and genuinely confronting our past, we have a great opportunity to imagine what we will be moving forward.”

The sit-in began after a lunchtime demonstration on the steps of Nassau Hall. With more than 200 people on the green, including Eisgruber, who stood silently at the bottom of the steps, students laid out their demands: that the University administration “publicly acknowledge the racist legacy of Woodrow Wilson and how he impacted campus policy and culture,” that the Woodrow Wilson School and Wilson College be renamed and a Wilson mural be removed from Wilcox Hall; that faculty and staff be required to take “cultural-competency training,” and classes on “the history of marginalized peoples” be added to students’ distribution requirements; and that there be affinity housing and campus space dedicated to black students and culture.

Then about 60 students walked into Nassau Hall, chanting, “We here, we been here, we ain’t leaving, we are loved,” many heading into the president’s office. After a short discussion with Eisgruber, the students settled in, playing music and working on schoolwork. Professor Joshua Guild brought the precept for his African American history course to Nassau Hall, saying the material was related to the protest and that “a third of the class was already there.”

Ruha Benjamin, a professor of sociology and African American studies, sent in pizza. Cornel West *80, a former Princeton professor now at Union Theological Seminary, phoned to offer support. Simmons, on campus to attend a regularly scheduled trustees meeting, stopped in to talk. The Rev. William Barber, leader of North Carolina’s “Moral Mondays” protests, who was speaking in the Chapel that night, visited to pray with the students.

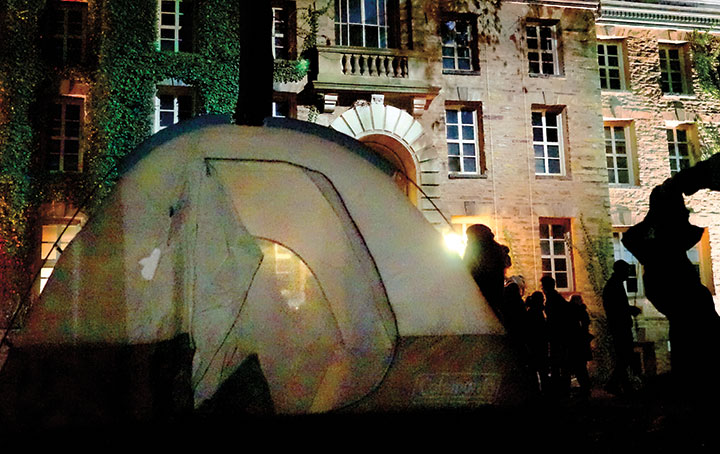

After the students were told that anyone who left the president’s office would not be allowed back, 17 students prepared to camp there overnight. More than 40 others pitched tents and laid out sleeping bags outside Nassau Hall. Rain woke the students as morning arrived.

At 8:30 a.m., the doors to Nassau Hall were unlocked and students returned to the atrium. Azza Cohen ’16, who had slept by one of the tigers outside the building, made a video in which protesters addressed why they were participating (see it at https://youtu.be/6e7FlS8q6F0). Activists have described a range of ways in which they feel unwelcome at Princeton, from casual suggestions by white peers and professors that black students are unable to do the work, to a paucity of black role models on the faculty, to anonymous threats on social media. (See page 17 for a Q&A with BJL members.)

At about 3:30 p.m., Eisgruber and other administrators returned to the office, and the two sides ultimately hammered out an agreement. In the document, administrators pledged, among other things, to “initiate the process to consider removal” of the Wilson mural (which Eisgruber supported); to begin conversations about Wilson’s legacy, including the request to remove his name from the Wilson School and Wilson College (which Eisgruber opposed); to designate four rooms in the Carl A. Fields Center for cultural-affinity groups; to begin discussions on designated housing “for those interested in black culture”; to work to “enhance cultural-competency training” for University counseling staff; to “arrange an introduction with BJL concerning the possibility of cultural-competency training” for faculty members; and to invite BJL to discuss a possible diversity requirement with the General Education Task Force. The agreement also stated that “no formal disciplinary action has been nor will be initiated if students peacefully leave” the office. Students left the building at about 8:45 p.m.

But alumni, students, and faculty did not agree on what should happen next. Three petitions — two opposing the BJL’s demands and one in support — appeared online. Student groups met to discuss the racial climate. A new student group called the Princeton Open Campus Coalition promised to promote “diversity of thought” and to oppose “a policing of free speech.” “I agree with the Black Justice League that diversity on campus is important,” said Evan Draim ’16, a founder of the Open Campus group. “However, we cannot achieve real diversity without academic freedom and free speech.”

The New York Times weighed in with an editorial endorsing changing the name of the Woodrow Wilson School. The Daily Princetonian took the opposite view. Scholars and pundits — in opinions collected at paw.princeton.edu — offered varying analyses, some arguing that Wilson was even more racist than most people of his time, others stressing his accomplishments as president of Princeton and then of the United States. (PAW will address Wilson’s legacy in more depth in a later issue.)

Wilson’s racism “should not eclipse the many great things he did at Princeton and in the world,” said Wilson biographer John Milton Cooper ’61, who laid out his record on both sides of the ledger. Among the positives, Cooper wrote: “He began the long march toward the transformation of a small, snobbish men’s college into this great diverse university that can vigorously question his views and legacy.” Cooper opposed a name change.

Another professor, Johns Hopkins’ Michael Hanchard *91, disagreed. “Monuments, as symbols, project values, not neutral representations of the past,” he wrote at The Huffington Post. “Based on [a] belief in the power of democratic social movements to transform values in a national society, I support efforts, whenever possible, to rename or remove monuments that directly or indirectly extol the deeds and character of historical figures most associated with genocide and the comprehensive marginalization of minority populations.”

In an email to the campus community following the sit-in, Eisgruber noted conversations about campus racism that have taken place for more than a year. “I have heard compelling testimony from students of color about the distress, pain, and frustration that is caused by a campus climate that they too often find unwelcoming or uncaring ... ,” he wrote. “Our students deserve better, and Princeton must do better.” He said Princeton would respond through “appropriate University processes” and highlighted work already underway to increase diversity and equity on campus.

“More remains to be done,” Eisgruber said. “I care deeply about what our students are saying to us, and I am determined to do whatever I can ... to improve the climate on this campus.”

Some professors endorsed the students’ demands and supported the activists. Among those who did not was Professor Stan Katz, in the Woodrow Wilson School, who said he was most alarmed by the demand to add a distribution requirement. “It’s wrong for the University to send a signal that what we’re most concerned about is people’s feelings,” he said. “This is not the university of feelings; this is the university of knowledge.”

There was also concern about the students’ tactics, including what some saw as a lack of respect for Eisgruber. “Hearing student protesters shout down President Eisgruber shocked and embarrassed me,” Dean of the College Jill Dolan wrote in a letter to the Prince, but other moments “gave me hope that our community might in fact do better.” She went on to emphasize other, more productive conversations about racial justice that took place during the sit-in.

In the weeks after the sit-in, Dean of the Faculty Deborah Prentice said that some departments have inquired about funding for voluntary cultural-competency training. Dolan said that at a General Education Task Force meeting on the potential revision of distribution requirements, students provided “incredibly articulate, nuanced, multiple perspectives on what a diversity requirement as part of the general education requirement might mean.” Vice President for Campus Life Rochelle Calhoun said the Carl Fields Center plans to have four rooms ready for use by cultural-affinity student groups by the beginning of the spring semester. The BJL hopes to meet with the Board of Trustees to discuss its demands.

Student activism has continued. A teach-in Dec. 12 on “Black Activism and Consciousness at Princeton” drew about 100 people; students and faculty discussed campus racial issues and the challenges of defining a black identity. Wilglory Tanjong ’18 said the BJL, which sponsored the teach-in, is “pushing for the same demands that black students in the ’60s and ’70s pushed for.”

The Association of Black Princeton Alumni issued a statement: “We are heartened by the activism of the black students on campus, and share many of their frustrations in light of our collective experience as black Princetonians and blacks in America.” The statement noted recent progress that has been made on campus, and said it stood ready to “assist our students, President Eisgruber, and the broader community in achieving a more welcoming, diverse, and inclusive Princeton.”

15 Responses

Mack Rossoff ’74

10 Years AgoA Contrast in Protests

Reading “Occupying Nassau Hall” (cover story, Jan. 13) brought back memories. In 1972 I joined about 100 other Princeton students for a sit-in (our term for “occupy”) at Nassau Hall. We took over the main room, site of trustee meetings, and demanded an end to the Vietnam War — or, at least, the elimination of ROTC on campus. Amid clouds of marijuana smoke, the strumming of folk guitars and some extracurricular activities by couples in the dark corners, we chanted our slogans: “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, NLF is gonna win!” President Robert Goheen ’40 *48 entered the room, with aides in tow, to address us, and we shouted him down. The poor, bow-tied man, the picture of academic dignity, turned on his heel and walked out. To my memory, it was reported that he then uttered the phrase that often would be quoted: “This isn’t Princeton,” although PAW places this catchphrase sometime earlier, at a protest at the Institute for Defense Analyses.

What a contrast with the protest of the Black Justice League. The students are polite, they speak with President Eisgruber ’83 for five hours, they chant about love. The demand is for “cultural competency training” and affinity housing; they do their homework. The picture that accompanies the article says it all: These are respectful young people, polite, diverse, dialoguing, posting, and, apparently, effective. The demands, if not wholly met, will be addressed. This is Princeton.

As for my crowd, we were photographed individually by campus security and arraigned in student court. I received a year of disciplinary probation — not a trivial matter when a false move thereafter would have resulted in expulsion, loss of my student deferment, and service in the wartime U.S. Army. But there was a bright side: We did get rid of ROTC, and we ended the Vietnam War.

Ben Fuller ’67

9 Years AgoThe Impact of Protests

I beg to differ with Mack Rossoff ’74’s conclusions (Inbox, March 2). As I recall, by 1972, effective student protests had happened (not at Princeton), and the politicians were slowly extracting us from Vietnam. Princeton was late to this party. He is correct in that ROTC was shut down, not necessarily to the service of the nation. It is rare now for a Princeton student to serve, or to know people who do. That is especially important when these students become political leaders, as we are now seeing. Long gone are the concepts of citizen soldier, of pay as you go for military adventures, of having responsibilities as well as rights.

Princeton Alumni Weekly

10 Years AgoThe Wilson Legacy, and What to Do About It: Readers Respond

The demand by student protesters that the University rename the Woodrow Wilson School of International and Public Affairs and the Wilson residential college prompted many letters, Web comments, and Facebook posts from alumni. Here is a sampling; expanded versions and additional viewpoints can be found at PAW Online.

Have we all lost our minds? I am generally horrified that the University is contemplating removing Woodrow Wilson from the institution’s history, renaming both the School of Public and International Affairs and a residential college and erasing a mural in the Wilson dining hall because of an on-campus movement that claims his legacy makes certain students feel unsafe. To quote one student from a recent New York Times article, “For black students, having to identify with someone who did not build this place for you is unfair.”

I am an alumna. Princeton didn’t build this place for me, either. Should we now remove all paintings and building names of men associated with the University prior to 1969, the first year the University admitted women? Following similar logic, should we nullify all degrees conferred prior to 1972, since women were not eligible? Should we erase all legacies that began with families whose Protestant great-grandfathers attended the school? Let’s be honest, Princeton was not built for anyone non-white, non-male, and non-Protestant, yet among his racist convictions, Wilson was the first University president to admit Catholics and Jews. If not for that step, perhaps none of the diversity represented on campus today would have come to pass.

My parents taught me nothing comes of throwing temper tantrums, yet would-be tantrums are sweeping the nation’s campuses. Where is the American ethos of bucking up, holding your head high, and getting your job done? I work in an industry that is 83 percent male worldwide — 83 percent. I am degraded, belittled, and offended almost daily. Big deal. Should I cry to my bosses (who are also all male) that isn’t fair? No. I go to work every day, do the best job I can, earn respect, and change the industry from within. I am proud this country evolved to offer me a seat at an all-male table, even though the table wasn’t originally built for me. We need to embrace our history and how far we have come, not erase it.

Michelle M. Buckley ’01

Boston, Mass.

To change a name is awkward; the unfortunate issue is Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs was named for Thomas Woodrow Wilson.

Better to admit a mistake than to live with it forever ... “Dare to be true.”

Bayard Henry ’53

Westwood, Mass.

What is happening to Princeton? Better: What is happening to all our colleges and universities? I graduated with a Ph.D. from Princeton in 1966. I have been teaching ever since. In the 50 years since I first entered the classroom, I have seen a steady decline (increasing in rapidity of late) in student performance and commitment ... and it has nothing to do with diversity or prejudice.

It has to do with entitlement and litigation: the crossroads of what is wrong in America today. As a society we have made great strides to eliminate the unfairness and preferential treatment that prevailed in the “Golden Years” of our country (the ’50s); yet, in the face of this progress, we see not gratitude but increasing demands for “rights”: black rights, gay rights, even graduate-student rights!

A recommendation: Don’t give in to the pressure of a few activists who would besmirch the legacy of Woodrow Wilson. Should we disenfranchise Thomas Jefferson because he owned slaves? And one other suggestion: Get back to the business of education, rather than social activism. Princeton is an institution of higher learning, not a lackey for any group with an agenda and a few activists who take over campus buildings and play CEO for a day or a week.

Marvin Karlins *66

Riverview, Fla.

I was 30 years an alumnus before I learned the racist component of Wilson’s administration at Princeton and in Washington as president. I do think that Princeton’s veneration should be downsized considerably. For example, there’s very little reason why Wilson College should be named after him. However, I do not believe expunging his name entirely makes sense, because the likely result would be that most future undergraduates would be oblivious to what can be learned from contemplating both the laudable and reprehensible history of this influential man.

I recommend leaving Wilson’s name on the School of Public and International Affairs because he did exert some positive influence in that sphere. The school also could offer a useful source and focus on his entire history, the ugly as well as the good. There is value in recognizing that the celebrated among us nevertheless are humans who hardly ever merit being idolized.

Murphy Sewall ’64

Windham, Conn.

If Princeton students cannot solve problems working together as undergraduates, how will they be able to work together as our nation’s future leaders in many fields? Come on, don’t expect the administration to solve your challenges; work them out yourselves. It will benefit both the University and your own development.

Clifton White ’62

Venice, Fla.

Following events as well as I could from the West Coast, I thought the University administration handled well the sit-in having to do with Woodrow Wilson. As someone whose undergraduate major was the Woodrow Wilson School, I would like to propose that, if the school’s name were to be changed, we consider renaming it the Dulles-Stevenson School (or the Stevenson-Dulles School).

John Foster Dulles 1908 was Secretary of State in 1953–59 and ran America’s foreign policy for six critical years during the Cold War. He was also briefly a U.S. senator from New York. Adlai E. Stevenson II ’22 was governor of Illinois in 1949-53 and the presidential nominee for the Democratic Party in 1952 and 1956. He served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in 1961–65 (he died in office).

This combination has the advantage of including a prominent Republican and a prominent Democrat, and therefore doesn’t appear partisan. It also may be a good idea to establish a precedent that the School of Public and International Affairs (which is now 85 years old) changes its name every two or three generations. Given the caliber of the people who attend Princeton, there are bound to be alumni who achieve distinction in public service every 50 to 75 years and deserve to be honored.

Bing Shen ’71

San Francisco, Calif.

As an alumna, I appreciate President Eisgruber’s proactive communication with us, and applaud his efforts to defuse a volatile situation. But I must take issue with the scope and tone of the protesters’ “demands,” and respectfully disagree with the University administration’s seeming capitulation to noisy threats and unpleasantries.

Woodrow Wilson, in his day, would not have wanted me to attend Princeton either. But I am proud to be among the first generation of women to have attended Princeton. I am honored to have enjoyed the friendship and intellectual comradeship of my fellow students, brilliant and forthright persons of varied races, ethnicities, beliefs, and nationalities.

The Princeton I attended taught me, first and foremost, that knowledge and understanding are acquired not by surrounding oneself in a cozy echo chamber where one is sheltered from conflicting — and at times uncomfortable — views, but obtained only through exposure to all viewpoints, serious examination thereof, reasoned discourse, and the resulting ability to formulate, test, question, express, and support one’s conclusions. Today’s Princetonians deserve nothing less.

Nan Moncharsh Reiner ’77

Alexandria, Va.

As a WWS MPA graduate, I am closely following the ongoing debate. History shows that Woodrow Wilson was perhaps among our country’s most complex presidents, leaving behind a uniquely contradictory legacy. He was a model progressive on many issues, both international and domestic. It was on the basis of those dimensions of his legacy, together with his contributions to Princeton, that he earned the honor of having his name placed on our beloved school.

At the same time, he was a deeply bigoted individual who turned back the clock on race relations with sweeping decisions that were even then considered to be out of date and much more racist than the dominant racial thinking in most of the U.S. at the time. The legacies of his thought and actions have weighed heavily on our country’s subsequent history. They have caused deep and irreparable harm to countless millions of African Americans while damaging the character and conscience of even larger numbers of complicit white Americans over the past century.

I respect the courage, aims, and timing of the Princeton students, and strongly support them in their demand for an end to the almost saintly reverence given to Wilson on the Princeton campus. To this end I join my voice to their demands for changing the name of our school. I believe it not only correct, but imperative, that we send a clear signal of the values on which our school stands and for which we work.

Peter Matlon *71

Washington, D.C.

I am gratified to see that letters on the Wilson issue reject this attempt at revisionist history, as I emphatically do. To conflate Wilson’s brilliant educational achievements at Princeton and his many other civic contributions with his abysmal racial bias is simply absurd. It is ironic that Wilson was such a controversial figure as University president that it took a generation before his name was finally added to SPIA in 1948, and now we get this misguided attempt to delete him from the record. I am proud to be the sixth Hibben to graduate from this great university, and nothing will ever change that, but if Wilson is expunged from Princeton, he takes me with him.

Stuart Hibben ’48

Swarthmore, Pa.

In discussing the record of Woodrow Wilson and his legacy on our campus (including his views on race), it is very important to realize that this is not the first time that Princeton University has had this discussion. The 2006 Princeton Colloquium on Public and International Affairs, April 28–29, 2006, titled “Woodrow Wilson in the Nation’s Service,” was a University-wide collaboration and was part of the year-long 75th-anniversary celebration of the WWS and coincided with the 150th anniversary of Wilson’s birth. The final report of the colloquium provides important background to the current discussion and can be accessed at: http://bit.ly/PCPIAreport.

Charles Plohn Jr. ’66

Princeton, N.J.

WEB EXCLUSIVE LETTERS

Posted Jan. 11, 2016

We learn nothing today when passing through the doors of the Woodrow Wilson School about its namesake. It is time for the building to speak. Two situations come to mind that can assist the Princeton community in coming to grips with history which we must write and not rewrite. I ask that the lessons learned from these examples, rather than the examples themselves, guide us forward.

After Deng Xiaoping came to power in China, he recognized the need to grapple with the legacy of Mao Tse-tung, who both created him and did him in. Recognizing the peril of denying the past, Deng contrived a formula pulling the rug out from under a demigod, pronouncing him 60 percent good and 40 percent bad. The proportions don’t signify. What matters is that imperfection trumped a charade, thereby liberating Chinese people from the straitjacket of dogma. It is easier to pay lip service to Mao than be forced to worship him.

Not long ago, I had the opportunity to visit the Reichstag in Berlin. If ever there were a building burdened with history, it is this one. Add to that a stunning renovation which enabled the building’s current role as seat of German government, and we can sense the complexity of the Reichstag’s stature in the present. As I approached the iconic building, best remembered aflame from old black and white footage, I grew anxious. But before my thoughts could further deteriorate, I was well inside the building, being greeted by truth; and it was the image of the burning building itself, up front and center, that allowed me to see it beyond a singular moment in time. But the Reichstag is not named for anyone.

I propose that a narrative be prepared on behalf of all of Woodrow Wilson that is then physically woven into the building and even allowed to spill out onto the plaza. We can all keep learning at Princeton. That’s a walk in the park compared to China and Germany.

Peter Rupert Lighte *81

Princeton, N.J.

I was momentarily heartened by President Eisgruber ’83’s first reason for agreeing to re-examine Woodrow Wilson’s Princeton legacy: “As a university we have an obligation to get the history right” (President’s Page, Jan. 13). Personally, I’ve never been a fan of Wilson’s politics or his "in the nation’s service” slogan. But Princeton did embrace them, and he was Princeton’s president, as well as the nation’s president. So let’s move on.

More worrisome is that Wilson’s true legacy is that we may be forever forced to deal with the already virtually infinite but still expanding evidences of discrimination and bias in our society, as recommended in the Whistling Vivaldi Pre-read. While President Eisgruber characterizes the sit-in as just Princeton’s version of nationwide campus unrest, he should re-examine the potential for our policies to expand and exacerbate such unrest. In the current agitated atmosphere, which we are catering to in a special Princeton way with our aggressive diversity focus in faculty hiring and admissions, as well as the Whistling Vivaldi Pre-read, such policies are incendiary.

I heard with dismay that the frosh trip of Outdoor Action (the name of the Princeton Outing Club I once loved, whose name change apparently is, as I feared it would be, a harbinger of its new purpose) is now going to be required of all freshmen, and that the curriculum (there is no other word for it) will heavily emphasize “leadership training"” with a focus on how to mitigate "”stereotype threat,” as laid out in Whistling Vivaldi. This is indoctrination pure and simple, with the intent and effect of giving credence to such actions as those of the protesters. Although I suspect Woodrow Wilson would approve, I see no reason for Princeton today to adopt such policies unless we truly mean to elevate political indoctrination over education as we have mandatory discussions of how to create “safe spaces” around the campfire, where the talk used to be about what climbs we would try tomorrow.

As to “getting the history right,” I used those very words in a book I wrote last year to describe an end-of-life obsession of a deceased Wall Street historian named Walter Werner, whose works alerted me to a little-known fact of our nation's history as I was researching the origins of stock exchanges. Certainly during the time of our nation’s founding (and probably of Princeton’s founding almost half a century earlier), and throughout the 19th century, the right to discriminate in our associations on any basis we saw fit was simply assumed. It did not appear to depend on laws or the rights in our Constitution, such as the religious freedom in the First Amendment of our Bill of Rights, or anything else. It’s just the way it was. Although I was primarily interested in how that right made us a rich nation, a corollary is that we were also a much less contentious nation.

Scratch the surface of any of the protesters’ demands and you will find a supposed requirement that our society, and Princeton, advocate and allow the redistribution of wealth or advantage to the protesting groups. Under such a policy, how can we expect anything other than the continuing escalation of those demands presented in ever more violent fashion? Unless we want Princeton itself, and not just Nassau Hall, to be perpetually “occupied,” maybe it’s time to re-examine not history, but our fundamental policies.

Steve Wunsch ’69

New York, N.Y.

The Jan. 13 issue of the PAW, focused on the Black Justice League and the sit-in at Nassau Hall, was the most interesting and substantive I’ve read in the 25-plus years since I graduated. My years at Princeton in the early 1990s were marked by near-catatonic political apathy among students; aside from “Take Back the Night” marches and “Gay Jeans Day,” a tepid attempt to support LGBT classmates, I recall few to no signs of widespread political action or protest on campus. Even the Gulf War inspired little more than a few American flags flown from dorm windows. Whether or not one agrees with the current protests over race issues at Princeton, we ought to be heartened that today’s students are again embracing the engaged and rebellious role that has been the traditional purview of students since the days of the Paris barricades.

And as for the outpouring of letters to the PAW from alumni bemoaning this state of affairs, I suppose they, too, are to be congratulated on having embraced their own traditional place as crusty curmudgeons complaining about today’s spoiled and clueless young people. Don’t worry, one day the Class of 2016 will be writing in to complain that the Class of 2066 just doesn’t get it, either.

Zanthe Taylor ’93

Brooklyn, N.Y.

As a serendipitous survivor of the Holocaust and a grateful Princeton Graduate School alumnus, I read with concern about the revisionism proposed by those who would expunge the name of Woodrow Wilson from the hallowed halls of the University. Racial prejudice toward my people has existed for millennia, and yet no one in the Jewish community has ever suggested the erasure of great contributors to society, even those who may have harbored unjust and unjustifiable notions. Surely Wilson was a very major figure in the history of Princeton, of the nation, and even of the entire world. His unfortunate prejudices, alas, were part and parcel of the time, and if we have come a long way in the interim, his work in developing a climate of the universality of mankind is partly responsible and deserves reverence, despite his flaws.

George Sturm *55

Englewood, N.J.

I am a lover of and enthusiastic supporter of Irish Letters – embracing poetry, history, theater, and prose – at the University. I have been responsible for bringing important Irish Catholic literary figures such as Clair Wills, Fintan O’Toole, and Colm Tóibín to teach at Princeton, as well as continuing to support the work of my friends the poet Paul Muldoon and the Lewis Center head Michael Cadden.

Most Princetonians are unaware that both the town and University were named for the English Protestant king, William III of the House of Orange-Nassau, who defeated the former English Catholic king, James II, at the Battle of the Boyne. William thereby displaced Oliver Cromwell as the most hated man in Ireland but was fondly called “King Billy” by supporters, including a few bearing the surname Wilson. Professors Cadden, Wills, and O’Toole, I know, are aware of King Billy’s background. One can almost feel the pain they endure daily to hear and read the name Princeton. Undoubtedly, some students of Irish Catholic descent are inflicted with a similar hurt.

I believe that Scott Fitzgerald ’17 never completed his degree because he was so embarrassed singing “Old Nassau,” and Eugene O’Neill 1910’s actor father, James, is known to have detested the color and fruit orange. I respectfully request that President Eisgruber ask Kathryn Hall ’80, chair of the Board of Trustees, to appoint a committee to examine the possibility of renaming Princeton the College of New Jersey, as it was known between 1746 and 1896. President Eisgruber might also approach the town council about restoring the 18th-century name Stony Brook to the municipality. Nassau Street would become Route Two.

Leonard L. Milberg ’53

Rye, N.Y.

My commitment to racial justice developed in part due to my experiences majoring in the Woodrow Wilson School and participating in Sustained Dialogue on campus. I’m concerned about the tone of reactions from many alumni about the request of student advocates to rename places on campus.

I encourage people who care about the future of Princeton, our nation, and the world to read James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me and learn about the renaming of places in other countries. To understand the context of the discussions occurring, we must consider both the dominant narrative in America and the history of healing elsewhere after segregation, genocide, and colonization. For example, South Africans renamed places after apartheid.

As an educator, I hope the alumni community will interact respectfully with students who act as engaged citizens, regardless of whether we agree with their opinions. Let’s listen with an open mind, model civil discourse, and always consider how we can support bending the arc of the universe toward justice.

Cindy Assini ’04

Hillsborough, N.J.

I join the vast ranks of Princeton alumni who will boycott Alumni Day festivities in protest to its Woodrow Wilson Award, specifically in protest to the University for having taken no action of any sort with regard to Woodrow Wilson’s blatant printed racist comments.

The fact that he was growing up in the Confederacy (Stanton, Va.) during the Civil War accounts for, but does not condone, his extreme views recounted a century and a half later. Yes, he was an outstanding president. But no, we cannot continue to have him glorified in the same measure as in the past, nor should we need to have these quotes thrown back at us again and again because the University prefers to sweep the issue under the carpetbag.

Even though I belong to no minority group, I am shocked and embarrassed by the University’s inaction, and some explanation or apology is certainly due to the greater University community.

Paul Hertelendy ’53

Berkeley, Calif.

Posted April 22, 2016

My Princeton class was the first one assigned to residential colleges, an innovation Wilson hoped would foster a “spirit” of “learning.” On a campus dotted with landmarks that bore the names of industrial titans – Firestone Library, Rockefeller College, Lake Carnegie – he was the counterpoint, the scholar-politician whose example ennobled us all.

Or so I thought. A few years ago, I read that federal agencies had segregated employees during President Wilson’s administration. Wilson’s record on Jim Crow – and my belated discovery of it – hit home. My husband is an attorney for the federal government in Washington. From 1996 to 2001, so was I. At my agency, race defined the ranks, with whites comprising most of the professionals and African Americans dominating the support staff.

There is a sizable disconnect between Wilson’s enshrinement at Princeton and his record on race. Princeton is way behind where it should be in confronting Wilson’s complexities, including his role in keeping the university all white. Perhaps it is time to look to other alumni and alumnae to represent and reflect its values.

Among current alums, Princeton would not have to look far. Two public servants come to mind: Supreme Court Justices Sonia Sotomayor ’76 and Elena Kagan ‘81. Renaming the Wilson School and Wilson College would not substitute for acknowledging Wilson’s history on race. But symbolism matters. As President Christopher L. Eisgruber ’83 said in his Nov. 22 email to the University community: “Our students deserve better, and Princeton must do better.”

Joan Quigley ‘86

Kensington, Md.

Joan Quigley is the author of the forthcoming book, Just Another Southern Town: Mary Church Terrell and the Struggle for Racial Justice in the Nation’s Capital.

Cindy Assini ’04

10 Years AgoThe Wilson Naming Issue

My commitment to racial justice developed in part due to my experiences majoring in the Woodrow Wilson School and participating in Sustained Dialogue on campus. I’m concerned about the tone of reactions from many alumni about the request of student advocates to rename places on campus.

I encourage people who care about the future of Princeton, our nation, and the world to read James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me and learn about the renaming of places in other countries. To understand the context of the discussions occurring, we must consider both the dominant narrative in America and the history of healing elsewhere after segregation, genocide, and colonization. For example, South Africans renamed places after apartheid.

As an educator, I hope the alumni community will interact respectfully with students who act as engaged citizens, regardless of whether we agree with their opinions. Let’s listen with an open mind, model civil discourse, and always consider how we can support bending the arc of the universe toward justice.

Leonard L. Milberg ’53

10 Years AgoThe Wilson Naming Issue

I am a lover of and enthusiastic supporter of Irish Letters — embracing poetry, history, theater, and prose — at the University. I have been responsible for bringing important Irish Catholic literary figures such as Clair Wills, Fintan O’Toole, and Colm Tóibín to teach at Princeton, as well as continuing to support the work of my friends the poet Paul Muldoon and Lewis Center head Michael Cadden.

Most Princetonians are unaware that both the town and University were named for the English Protestant king, William III of the House of Orange-Nassau, who defeated the former English Catholic king, James II, at the Battle of the Boyne. William thereby displaced Oliver Cromwell as the most hated man in Ireland but was fondly called “King Billy” by supporters, including a few bearing the surname Wilson. Professors Cadden, Wills, and O’Toole, I know, are aware of King Billy’s background. One can almost feel the pain they endure daily to hear and read the name Princeton. Undoubtedly, some students of Irish Catholic descent are inflicted with a similar hurt.

I believe that Scott Fitzgerald ’17 never completed his degree because he was so embarrassed singing “Old Nassau,” and Eugene O’Neill 1910’s actor father, James, is known to have detested the color and fruit orange. I respectfully request that President Eisgruber ask Kathryn Hall ’80, chair of the Board of Trustees, to appoint a committee to examine the possibility of renaming Princeton the College of New Jersey, as it was known between 1746 and 1896. President Eisgruber might also approach the town council about restoring the 18th-century name Stony Brook to the municipality. Nassau Street would become Route Two.

Stanley N. Katz

10 Years AgoThe Wilson Naming Issue

The Princeton University response to the recent protests by what I take to be a very small number of Afro-American students has been (to me) very disappointing. I cannot be sure, but so far as I can tell, the sit-in group appears to be quite unrepresentative of the campus Afro-American community – so far as I can tell they do not represent the common opinion of Afro-American football players, for instance. And there does not seem to be any widespread general support on campus for the specific demands of the protesters, though how would one know for sure? If I am right about these facts, then I am doubly uncomfortable with the reaction of President Eisgruber to the sit-in. I am dumbfounded that agreements on University policy should be negotiated with a small group of protesters while they were still occupying his office. I thought the best strategy was not to negotiate with hostage-takers.

In general, in my view, President Eisgruber’s reaction has been to over-react to student allegations of emotional harm. “Microaggressions,” as the students term them, are mostly the kinds of grievances that adults realize they have to live with, and deal with in civilized ways. A community dedicated to eliminating such relatively minor harms, and punishing those “guilty” of them, is a repressive society with little capacity to tolerate dissent or encourage risky creativity. There is something about “safe” as a standard that seems to me hostile to the spirit of democracy and liberal education. I think we should be more or less free to do as we like, though liable for the real and tangible harms that we inflict on others, but the bar for what constitutes harm should not be set too low. Randy Kennedy ’77’s op ed in The New York Times Nov. 27 seems to me to express this notion beautifully.

I think we are all weary of the “naming” controversy at this point. Certainly I am. Suffice it to say that I think we should not remove the name of Woodrow Wilson from the School or elsewhere in Princeton University. Many of us have long been aware of Wilson’s defects, which were serious, but have nevertheless admired him for his accomplishments and what they have stood for over the years – both as a politician and as an educator. I took part in a wonderful conference organized here in 2009 by the distinguished historian of this university, Jim Axtell, on “the educational legacy of Woodrow Wilson,” which resulted in a 2012 book of the same name (for which I wrote the afterword). Although I have long been a public critic of Wilson’s racism, and once did a video on the subject, I came away from the conference convinced that Wilson was the most important of the architects of the modern American system of elite higher education in the early 20th century. And I still feel that way. I am honored to teach in a School that bears his name – and I do not see why that is incompatible with my complete rejection of his racial views.

Princeton and other institutions have plenty to be criticized for, considering our present policies and behaviors. I would feel better about the current protests if they were aimed at current issues, rather than intended to embarrass and shame current students and faculty who disagree. A vibrant civil society needs to encourage dissent of all kinds while maintaining respect for everyone in the society. In order to achieve such a condition, however, the leadership of the society needs to make clear what values and behaviors we should strive for. What we need now is a clear indication of what those values and behaviors are.

Editor’s note: This is an expanded version of the letter published in the Feb. 3, 2016, print edition.

Lee L. Kaplan ’73

10 Years AgoThe Wilson Naming Issue

When I attended Princeton, I already knew Wilson was a terrible Southern racist. I also understood that many Princeton presidents before him never would have admitted Jews to Old Nassau. There is some delicious irony in attending a school where various barriers and prejudices existed in the past — barriers that would have kept many of us from attending Princeton in past decades.

Perhaps we should step back and ask just how much can we (or should we) erase? Even the Constitution refers to three-fifths of all persons — i.e. slaves. And justly beloved Lincoln trimmed his sails on racial equality. The story of this country is evolution.

As for President Eisgruber ’83, he has my sympathy. In his place, I might have thrown the occupiers out of my office with (a) a snarl, (b) handcuffs, or (c) a tolerant smile, depending on my mood that day. But I think we have to remember that every day, his job entails dealing with outraged members of three disparate groups — alumni, faculty, and students. I am grateful not to have his job.

Stephen Lucas ’82

10 Years AgoThe Wilson Naming Issue

As a 55-year-old white male with respect for tradition, I was alarmed to see college protests spread to Princeton with the demand that Woodrow Wilson’s name and likeness be scrubbed from the campus. Are we really going to have to rename everything? But the more I read about President Wilson’s racist history, the more I was impressed — shocked, really — by the strength of the case for removal. He used his position as leader of the country to aggressively promote and implement racist policies throughout the federal government. How can we possibly excuse or stomach this behavior? It seems utterly beside the point to discuss what good deeds he may have done as well. In aggregate, his legacy is an ugly stain on our nation and our university.

Princeton has a great tradition of educational excellence. But what good is tradition that serves to fossilize such behavior? I feel much gratitude to the student protesters who brought this issue to prominence, and I hope the administration will ultimately resolve the matter by removing the offense as requested.

John H. Steel ’56

10 Years AgoThe Wilson Naming Issue

The incipient movement to banish the name Woodrow Wilson from the Princeton campus is misguided and should be confronted. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and a host of others whose names we revere had slaves. Instead, Princeton should look seriously at the policy of racism and anti-Semitism that prevailed at the time and caused the University trustees to overlook this very evident characteristic of its president. The shame falls on the University, not just Wilson.

And while the University re-examines its history of granting naming rights, it might take a hard look at whether it has standards for donors, and what they are. Is money the predominant requirement, à la Lincoln Center in New York? Or does the name represent something to be proud of, as a building or facility on the campus of one of the world’s great universities?

Keep the name, if for no other reason than as a reminder that bigotry and hate infect even the most highly educated and dedicated.

Eric Shullman ’15

10 Years AgoGiving Credit to Wilson

I write to correct the misconception that the name of Wilson College is simply an arbitrary way to worship Woodrow Wilson and sprinkle his name across campus. Most recently and alarmingly, PAW published a letter from Murphy Sewall ’64 (Inbox, Jan. 13) that stated “there’s very little reason why Wilson College should be named after him.”

In fact, naming Princeton’s first residential college after Wilson is perhaps the best example of honoring Wilson in an objective and appropriate way. Wilson was one of the first and most vocal proponents of bringing the residential-college systems of Oxford and Cambridge to American universities. He laid out his “quad plan” to the Princeton Board of Trustees in 1906, which eventually would be realized in the form of houses at Harvard, residential colleges at Yale and Princeton, and many other variations at universities across the country where students live in residential communities.

In the spirit of academia, the Wilson College name credits Wilson for a specific ideological contribution.

btomlins

10 Years AgoWeb Exclusive Letters: Wilson’s Legacy

A hearty thank you is due to PAW, author Deborah Yaffe, and all of the academic contributors to the article “Wilson Revisited” (feature, Feb. 3). The article is long overdue, which is an understatement. But at last, it gives all of us in the Princeton community a more complete understanding of the facts at the heart of the current controversy.

John Aerni ’78

Brooklyn, N.Y.

Of course Woodrow Wilson’s name should be removed from the school. I understand this legally takes a couple of days max.

Sure, John F. Kennedy wouldn’t let Sinatra bring Sammy Davis Jr. into the White House because Davis was married to a white woman, May Britt. Against those who would say remove JFK’s name from the airport and from Kennedy Center, some but not all might mitigate that his disgusting and un-presidential bigotry was expressed against an individual, or actually a couple. And Wilson is hardly redeemed by his purportedly letting in a few Jews, again individuals.

But Wilson’s unforgivable crime was enacted against an entire race in a systemic purge that removed and demoted all black civil servants from their established positions. This is not the same, as one female Princetonian argued in PAW, like not letting women in from the start – it would be like kicking them all out now. St. Paul let us in.

As a reality check, if a personal and individual example is what you want, read the recent New York Times op ed piece by a black New York law partner about how Wilson’s purge affected his grandfather.

Wilson’s heinous job-pogrom, which had no justification or precedent, has only just been elucidated by recent scholarship. This answers the question, “Why now?” Could there be any better demonstration of what a university of the liberal arts and sciences stands for than such a revision, based on meticulous, compelling new scholarship?

David V. Forrest ’60

New York, N.Y.

We cannot rewrite history. Wilson did a lot for the University, which A. Scott Berg ’71 described in his biography of the man. Racism is part of the human fabric and constantly needs to be addressed by Princeton and anyone else who encounters it, but Wilson should not be used as a scapegoat. I am reminded of the uproar created by our sophomore class when we petitioned for 100 percent of our members to be given invitations to join an eating club, and if that did not occur, the 600-odd who signed would turn down a bid if they received one.

Stokes Carrigan ’52

Beach Haven, N.J.

So, let’s see. We could rename Washington, D.C., something like Federal City?

Milton L. Iossi *67

Salisbury, N.C.

The Jan. 13 issue of PAW covers the debate over whether references to Wilson should be expunged from the campus. It also includes a list of the latest winners of Rhodes scholarships. After we have finished excoriating Wilson, we should ask whether it is appropriate to accept scholarships funded by the exploitation of the mineral resources of Africa and the murder and oppression of Africans. Princeton refunded Imee Marcos’ tuition to the Philippines on the grounds that her parents had obtained the money illegally; perhaps the assets that fund the Rhodes scholarship should be returned to the appropriate governments in Africa.

Stanley Kalemaris ’64

Melville, N.Y.

We learn nothing today when passing through the doors of the Woodrow Wilson School about its namesake. It is time for the building to speak. Two situations come to mind that can assist the Princeton community in coming to grips with history which we must write and not rewrite. I ask that the lessons learned from these examples, rather than the examples themselves, guide us forward.

After Deng Xiaoping came to power in China, he recognized the need to grapple with the legacy of Mao Tse-tung, who both created him and did him in. Recognizing the peril of denying the past, Deng contrived a formula pulling the rug out from under a demigod, pronouncing him 60 percent good and 40 percent bad. The proportions don’t signify. What matters is that imperfection trumped a charade, thereby liberating Chinese people from the straitjacket of dogma. It is easier to pay lip service to Mao than be forced to worship him.

Not long ago, I had the opportunity to visit the Reichstag in Berlin. If ever there were a building burdened with history, it is this one. Add to that a stunning renovation that enabled the building’s current role as seat of German government, and we can sense the complexity of the Reichstag’s stature in the present. As I approached the iconic building, best remembered aflame from old black-and-white footage, I grew anxious. But before my thoughts could further deteriorate, I was well inside the building, being greeted by truth; and it was the image of the burning building itself, up front and center, which allowed me to see it beyond a singular moment in time. But the Reichstag is not named for anyone.

I propose that a narrative be prepared on behalf of all of Woodrow Wilson, which is then physically woven into the building and even allowed to spill out onto the plaza. We can all keep learning at Princeton. That’s a walk in the park compared to China and Germany.

Peter Rupert Lighte *81

Princeton, N.J.

I was momentarily heartened by President Eisgruber ’83’s first reason for agreeing to re-examine Woodrow Wilson’s Princeton legacy: “As a university we have an obligation to get the history right” (President’s Page, Jan. 13). Personally, I’ve never been a fan of Wilson's politics or his “In the Nation’s Service” slogan. But Princeton did embrace them, and he was Princeton’s president, as well as the nation’s president. So let’s move on.

More worrisome is that Wilson’s true legacy is that we may forever be forced to deal with the already virtually infinite but still expanding evidences of discrimination and bias in our society, as recommended in the Whistling Vivaldi Pre-read. While President Eisgruber characterizes the sit-in as just Princeton’s version of nationwide campus unrest, he should re-examine the potential for ourpolicies to expand and exacerbate such unrest. In the current agitated atmosphere, which we are catering to in a special Princeton way with our aggressive diversity focus in faculty hiring and admissions, as well as the Whistling Vivaldi Pre-read, such policies are incendiary.

I heard with dismay that the Frosh Trip of Outdoor Action is now going to be required of all freshmen, and that the curriculum (there is no other word for it) will heavily emphasize “leadership training” with a focus on how to mitigate “stereotype threat,” as laid out in Whistling Vivaldi. This is indoctrination pure and simple, with the intent and effect of giving credence to such actions as those of the protesters. Although I suspect Woodrow Wilson would approve, I see no reason for Princeton today to adopt such policies unless we truly mean to elevate political indoctrination over education, as we have mandatory discussions of how to create “safe spaces” around the campfire where the talk used to be about what climbs we would try tomorrow.

As to “getting the history right,” I used those very words in a book I wrote last year to describe an end-of-life obsession of a deceased Wall Street historian named Walter Werner, whose works alerted me to a little-known fact of our nation’s history as I was researching the origins of stock exchanges. Certainly during the time of our nation’s founding (and probably of Princeton’s founding almost half a century earlier), and throughout the 19th century, the right to discriminate in our associations on any basis we saw fit was simply assumed. It did not appear to depend on laws or the rights in our Constitution, such as the religious freedom in the First Amendment of our Bill of Rights, or anything else. It’s just the way it was. Although I was primarily interested in how that right made us a rich nation, a corollary is that we were also a much less contentious nation.

Scratch the surface of any of the protesters’ demands and you will find a supposed requirement that our society, and Princeton, advocate and allow the redistribution of wealth or advantage to the protesting groups. Under such a policy, how can we expect anything other than the continuing escalation of those demands presented in ever more violent fashion? Unless we want Princeton itself, and not just Nassau Hall, to be perpetually “occupied,” maybe it’s time to re-examine not history, but our fundamental policies.

Steve Wunsch ’69

New York, N.Y.

I was deeply saddened and concerned by the turmoil and protests that have taken place on campus this fall, and I hoped to share my thoughts regarding the legacy of Woodrow Wilson at Princeton.

As most students of Princeton history will attest, Woodrow Wilson was the single most important individual in transforming Princeton into the vibrant university that it is today. His record in shaping the University for the better was unrivaled, both as a professor and as University president. Year in and year out he was voted the most popular member of the faculty, and countless students looked to him as a mentor. His parlor became a gathering place for informal student discussions, which Wilson frequently continued on evening visits to student dormitories. It was in Wilson’s parlor also that the honor code, which put an end to the prevalent culture of cheating by entrusting students to oversee their own examinations, was born – an innovation that remains to this day. His lectures and scholarship, most notably exemplified in his famous “Princeton in the Nation’s Service” speech at the University’s sesquicentennial in 1896, provided Princeton with an inspirational vision for its goals in education and the place to which it should aspire in national life.

Wilson carried this vision with him during his eight-year tenure as Princeton’s president. From the auditorium within Alexander Hall and from the steps of Nassau Hall, he outlined his plans and ideals for his beloved alma mater in his similarly titled inaugural address, “Princeton for the Nation’s Service.” (It should be noted that Wilson caused a good deal of controversy among alumni by inviting Booker T. Washington as an honored guest to his inaugural ceremonies.) Wilson’s energetic and enlightened leadership transformed Princeton and brought about many of the most recognizable and distinctive features of the University today, many of which we now take for granted but which were quite revolutionary at the time. With the ever-present aim of bringing a spirit of intellectual fervor to the center of Princeton life, Wilson tightened academic requirements, instituted administrative and curricular reforms (including academic departments and majors), and oversaw the advent of the preceptorial system (thereby shifting the educational focus from memorizing to learning).

His two famed unsuccessful undertakings – to replace the eating clubs with a system of “quads” or residential colleges and to locate the new graduate college in the heart of campus – were both intended to further this goal of infusing campus life with democratic principles and a spirit of intellectual endeavor. (Our current residential-college system, so central to student life, represents the belated fulfillment of Wilson’s “Quad Plan,” and for this reason the first residential college is aptly named in his honor.)

Wilson’s tumultuous tenure at the helm of Princeton was followed by several decades of sleepy complacency in retaining but not expanding his program of reform; that was left to the second half of the century following World War II. The momentous reforms that have occurred at Princeton since that time – from residential colleges to the admission of women and minority students to further curricular and scholarly innovations – all rested on the principles of democracy and the power of intellect to better the world that Wilson laid out during his presidency. As he admonished his young collegiate listeners, “You are not here merely to prepare to make a living. … You are here to enrich the world, and you impoverish yourself if you forget the errand.”

It is for this reason that we must always hold Wilson’s legacy dear at Princeton. Yes, let us be frank about his faults. But in so doing, let us always remember his transformational vision for our University, a vision that is still shaping Princeton to this day. To remove his name from campus institutions, to take down his mural from a public place dedicated to his memory, or to otherwise qualify his legacy in word or deed, would be an enormous disservice to the shared heritage that all Princetonians have the privilege to cherish.

Matthew A. Frakes ’13

Langhorne, Pa.

I think it’s a good development that the Black Justice League has forced the Princeton community to confront openly the unfortunate legacy of Woodrow Wilson with regard to racial relations. Because Woodrow Wilson permitted U.S. government departments that had been integrated to be segregated, he was complicit in a policy that turned back the clock, reversing progress that had been made after the Civil War. This policy was, as the saying goes, on the wrong side of history.

I have given some thought to whether Wilson’s name should be removed from the School of Public and International Affairs and/or the residential college. One possible compromise that might have appeal would be to keep Wilson’s name, but then add another name that would reflect the University’s acknowledgement of Wilson’s failures in the area of racial relations. Suppose the name of the Wilson School were changed to the Wilson-DuBois School of Public and International Affairs. In adding the name of the great civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois, who supported Wilson in the 1912 election, but then did not support him four years later because of Wilson's segregation policy, Princeton would be honoring a man who got right what Wilson got wrong. However, Wilson would still be honored for the many other things he did that were worthy of honor and recognition.

Would it matter that Princeton would be putting the name of a non-Princetonian on the School? I don’t think it matters. It would be an implicit acknowledgment that Princeton itself was not integrated in Wilson’s era, and so there could not have been an African American civil-rights leader from that time who was a Princetonian.

James H. Bernstein ’75

New York, N.Y.

Although I applaud the inclusion of alumni into the process concerning recent events on campus, I am still disappointed with the University’s acquiescence to the vocal Black Justice League (BJL). None of these students were concerned enough about the existence of the Woodrow Wilson School to deter them from applying. The demand that Wilson’s name must be removed as it is too offensive to current students – despite having full knowledge of Woodrow Wilson’s role at Princeton prior to applying, then applying to the school, and agreeing to attend our prestigious university – is disingenuous at best. If today’s students are so upset by the legacy of Wilson dating back over a century (or Disney, Ford, Madison, or Jefferson, for that matter) that it is such an emotional issue for them, then Princeton is failing to prepare its students for the real stresses that occur in professional life.

Several alums have been particularly incensed about the comments made in the video from a BJL member during the sit-in that Princeton owes them something. I firmly believe that Princeton doesn’t owe anybody anything. Princeton provides professional opportunities as well as personal and educational experiences that are desired by over 10,000 students every year, of which only a select handful have the opportunity to appreciate. The fact that members of the BJL feel so entitled that Princeton owes them anything at all, without appreciating the opportunity that Princeton students have, is troubling. I understand the importance of these issues and what is happening at universities across this nation. That being said, Princeton is a leader in the nation’s service, and agreeing to any proposed changes from the group that happens to be most vocal, without understanding the ramifications of these actions and its effects on the various other constituencies that make our university so great, would be a mistake.

Richard Mandelbaum ’87

Livingston, N.J.

As a proud “bug” (member) of the Class of ’70, I was very interested in the article, “Decades of Activism, A Protest Timeline” (On the Campus, Jan. 13). Bugging the system was an integral part of my experience at Princeton. Though the article seems to confine itself to “generations of students [who] have protested a wide range of issues,” my favorite meaningful memories of protests involved faculty and even the entire University. Protests against the Institute of Defense Analysis (IDA) being on campus were carried out on several occasions and involved some prominent professors putting themselves on the line in the midst of students. It may have been their presence that contributed to a peaceful intervention by the National Guard to break up the protest, unlike the Kent State incident.

Also, my proudest moment at Princeton was when the entire University, in the nation’s service, took a leadership position by being the first to go on strike after the announcement of the secret bombing of Cambodia. Such peaceful protest is a very valuable aspect of a liberal-arts education. Relevant action must be allowed to accompany academic experience to maintain a holistic approach to education of whole people. Then-president Robert Goheen ’40 *48 was masterful in his accommodation of our passion. I carry on my education in peaceful protest, sometimes involving civil disobedience, in the realms of climate change and wilderness preservation.

Larry Campbell ’70

Darby, Mont.

I am writing in response to “Occupying Nassau Hall” (On the Campus, Jan. 13). I could not help but feel very sad for those students. If they feel threatened or scared walking around the campus of Princeton University, they have no idea about the real world awaiting them.

The world is a scary and dangerous place right now, but not in central New Jersey. From 2007 to 2009 I was in Iraq, fighting the anti-IED explosives fight. That was a scary world. Snipers shot at anyone moving down the roads, regardless of race or sex. Every pile of rubble was a possible roadside bomb that was designed to take your legs off, if not kill you. Worse, sectarian assassinations and kidnappings were normal.

I presently live in Germany and work for the U.S. Africa Command. In this idyllic European country, the culture clash of the tens of thousands of Middle Eastern refugees has spilled out of the camps and into the streets. German women are being sexually molested and beaten in the streets as large groups of young men patrol the train stations with nothing to do, no money, no hope, yet surrounded by a materialistic culture they will never really enter. In Africa, the continent is rife with murders, kidnappings, and near-constant war. Children are regularly targeted for capture and women are systematically abused, trafficked, and killed. Those problems are real, not hurt feelings of pampered students.

Yes, the world is a scary place, but not while a student of any color or creed is walking around “Old Nassau.” If those students feel threatened by a mural or the name of a man long dead, they have a lot to learn about the real world. They should spend their energy trying to prepare for the world they are about to enter.

Col. Jameson R. Johnson *03, retired

Stuttgart, Germany

I sent a letter to the committee and President Eisgruber ’83 (who graciously responded) concerning the problems of President Wilson. During his presidency, in addition to his racism as a Virginian, he was vigorously involved in suppression of women’s suffrage, which is well documented. He ordered women, including a Senator’s wife, sent to prison for demonstrating for suffrage in front of the White House gates. The president was widely lauded and narrowly focused on foreign affairs. He deserves his fame – positive or negative. He also deserves our refusal to accept denial of his active attempts to suppress suffrage. Apparently, women need to parade in front of Nassau Hall to make that point heard. Let’s be honest and still respectful of the times in which he served. At the same time, can we laud a man without notice of the serious national flaws that he denied?

Arvin Anderson ’59

Vero Beach, Fla.

What with multicultural racial division and strife front and center, gender bias highlighted concerns, student diversity in numbers alone but with groups proliferating in their own little boxes, sexual mores, hookups, and sexual-assault headlines featured, alcoholism in full swing at club parties and the infirmary, athlete-students existing in their own tight-knit universe practicing and playing to the exclusion of knowing many others, more credits offered appealing to the narrow focus of social and racial interest groups and the growing embrace of proliferating essentially trade-school courses in finance, entrepreneurship, and ballet and other “key” majors and certificates, where is the time left to engage in rigorous academic studies in the core humanities and sciences that once defined our liberal arts “elite” university the equal of Oxford or Cambridge? That curriculum used to demand time and attention to burn the midnight oil. Or is this what a Princeton education has come to?

Instead of fretting over the name Wilson (but better to have been Harvard’s TR as a national leader to symbolize), whose name proliferates rightly or wrongly on a campus historically replete with naming rights of narrow-minded intolerant evangelical Protestant preachers, just get on with it. Figure out how to cope with a Middle East in chaos, climate change in full swing, consider how Shakespeare castigated and crucified statesmen and would have impaled our politics today, and go land that job in the equality-driven, social-activist intelligentsia of Queens-led Wall Street and Goldman Sachs to repay astronomical tuition and student debt.

For too many it looks like Princeton “in the nation's service and the service of all nations” is more of a way station to list on a résumé, not an end in itself with real academic rigor. But then, the execution of idyllic University policy has only itself to blame.

Laurence C. Day ’55

Ladue, Mo.

I was surprised that the main article in the Feb. 3 issue discussing the Woodrow Wilson controversy on campus was written by a paid freelance writer with an uncertain connection to the University. She provided a great deal of space to the arguments of the Black Justice League (BJL)), but barely mentioned the existence of the opposing Princeton Open Campus Coalition (POCC). It would have been more appropriate and more informative if PAW could have published the opposing viewpoints of the BJL and the POCC, presented by their members.

In fairness, I do note PAW's publication of a number of letters expressing various viewpoints, as well as the nuanced essay of Akil Alleyne ’08 (On the Campus, Feb. 3).

Harvey Rothberg ’49

Princeton, N.J.

A news bulletin: WE ARE ALL FLAWED!

I have been following the recent concerns about the character flaws of Woodrow Wilson. I had the good fortune to attend Princeton as a graduate student from 1960 through 1965. During those years I learned much in my own field, but I also learned much about Princeton and her history. Individuals like Madison, and McCosh, and Witherspoon, and Forrestal, as well as Wilson. It did not take long to appreciate their accomplishments, but to also note their flaws. Ten years ago I read the fine book The Making of Princeton University: From Woodrow Wilson to the Present. Its author, James Axtell, chronicled an impressive list of Wilson’s accomplishments, but it was also clear to an objective reader that Wilson was a racist. Then again, he was hardly alone. Washington, Jefferson, and Madison all owned slaves. Brown University, near my home, was founded by a slave trader. As my dear long-departed mother used to say, “The only perfect person walked on the water 2,000 years ago; the rest of us need to swim.” Carl Friedrich Gauss, arguably the greatest mathematician who ever lived, was grumpy, irascible, and irritated many. Ludwig van Beethoven, arguably the greatest composer of all time, was something of a tyrant to the musicians under him. The list could go on and on.

I propose a different metric. In baseball, one measure of offensive performance is a hitter’s batting average. In the 115 seasons of the modern era, the highest batting average for a full season was an astounding .426 by Napoleon Lajoie in 1901 (no, sports fans – it was not Ted Williams’ .406 in 1941). Thus, even for Lajoie, who briefly was the absolute best, the creme de la creme, he failed more often than he succeeded!

In the 50 years since I received my Ph.D. I have managed a few worthwhile contributions, but, like Lajoie, I have failed often. For years I was haunted by an inner voice that kept whispering, “With a Ph.D. from Princeton, you should do more.” I tried, often with every fiber of my being, only to perpetually fall short of “greatness.” Then, one day about 15 years ago, while sailing, a strange peace settled over me, and I realized that what really mattered was that I led a basically good life, and that when the ninth inning finally came around that I could say that perhaps, just perhaps, in spite of all my many failures, that I would leave the world a tiny bit better place than it was when I entered. It says in the Good Book, “Let him who is free from sin, cast the first stone.” Based on that enduring idea, I would like to learn about the perfection of anyone who would ever wield a chisel to remove the name Woodrow Wilson from some of Princeton’s hallowed buildings. All of us fail, and often, but some leave the world a better place. I believe it was so for Woodrow Wilson.

Paul F. Jacobs *66

Saunderstown, R.I.

In response to my classmate Len Milberg’s sensitive and deeply reasoned letter recommending the change of the University’s name back to its original, College of New Jersey (Inbox, Feb. 3), I would suggest that he has overlooked a major emotional hurdle in wide acceptance of the thought. Perhaps because he does not have a letter sweater of his own, he may not have considered what current holders of a letter sweater, such as myself, would have to do about the now confusing P. Might I suggest that the current letter be grandfathered as of the name-change date, at which time newly awarded sweaters could be emblazoned with CNJ.

James L. Neff ’53

New York, N.Y.

I was pleased to read Deborah Yaffe’s mention of William Monroe Trotter’s White House meeting with President Wilson (feature, Feb. 3). Because of his vigorous protests of Wilson’s allowing segregation of several federal offices, Trotter was ejected. WMT has been a hero of mine since he was the subject of my 1958 senior thesis. Critics of Wilson’s racism should appreciate how this African American 1895 Harvard graduate fought a valiant real-time battle with Wilson in 1914.

Charles Puttkammer ’58

Mackinac Island, Mich.

The objections to Woodrow Wilson in the original student protests and some scholarly follow-up seem to borrow from culture theory to create an argument whose full form looks something like this. Wilson’s legacy is part of an oppressive structure whose wealth, power, and privilege derive from the oppression of minorities and which continues to operate in the form of “microaggressions.” Supposing this is true, the only logical response for believers would seem to be leaving the University. They can continue to work for change at Princeton wherever they go, just as protesters have referenced different college campuses. But by remaining, these individuals cannot fail to be complicit in the very injustices that they criticize. They will graduate with a Princeton degree or hold a Princeton professorship with all the benefits of resources and all the prestige and recognition that goes with them. These things are not incidental to Wilson, but the direct result of his academic reforms. To benefit from the power structure while condemning it seems basically incoherent. While this continues, it seems to roll back the more extreme versions of the cultural critique.

Matt Conner ’88

Davis, Calif.

Thank you, PAW, for your article on Wilson and his legacy (feature, Feb. 3). I was struck by the realization that I, though a supremely uninvolved alum, am confident that the Princeton community will make an informed, ethical, and far-sighted choice on the matter of memorializing Wilson. So, the ties run deep.

I wish to relate, also, that I remember a casual discussion during my undergraduate years 1984-9 about the racism of Wilson, and my disappointment in that. At that time, I had no doubt, the ethos of Princeton rejected racism. I also felt that the contradiction in Wilson’s legacy was not talked about enough.

The recent PAW article brings this feeling to the fore. The story of the contradiction between Wilson’s immense achievements and his abhorrent racism is more epic than I had imagined. Examination of this story, in the best traditions of a liberal education, needs to be part of the Princeton undergrad experience.

Keeping the Wilson name on the campus, along with his story, both good and bad, could be part of this experience.

Will Warlick ’89

Salt Lake City, Utah

I was surprised that the main article in the Feb. 3 issue discussing the Woodrow Wilson controversy on campus was written by a freelance writer with an uncertain connection to the University. She provided a great deal of space to the arguments of the Black Justice League (BJL)), but barely mentioned the existence of the opposing Princeton Open Campus Coalition (POCC). It would have been more appropriate and more informative if PAW could have published the opposing viewpoints of the BJL and the POCC, presented by their members.

In fairness, I do note PAW’s publication of a number of letters expressing various viewpoints, as well as the nuanced essay of Akil Alleyne ’08 in the same issue.

Harvey Rothberg ’49

Princeton, N.J.