PAWcast: Linda Coberly ’89 on Continuing Efforts to Pass the Equal Rights Amendment

Grassroots campaigns are pushing the amendment forward

The Equal Rights Amendment, which guarantees gender equality, is only one state away from being added to the United States Constitution, thanks to revived grassroots campaigns that took hold in the wake of the 2016 Presidential election. Linda Terry Coberly ’89, the chair of the ERA’s Legal Task Force, speaks with host Carrie Compton about the many hurdles that have prevented the ERA’s passage since its introduction in the ’70s, and what will come next if a final state ratifies it.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: Hi, I’m Carrie Compton and you’re listening to Princeton Alumni Weekly’s podcast. The Equal Rights Amendment originated in the age of suffrage, but it has yet to be ratified. It is short but profound: “Equality of rights under law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” Today I’m speaking with Linda Terry Coberly, Class of 1989, a Chicago-based attorney with Winston and Strawn who serves as the chair of the ERA Coalition’s Legal Task Force. In 1972, both houses of Congress passed the ERA, and 22 states quickly moved to ratify it. In the face of conservative opposition, however, ratification slowed, and in 1982, when the deadline for ratification had arrived after one extension, the amendment was short by three out of the 38 states needed. Since 2017, a new push for passage of the ERA has seen Nevada and Illinois both ratify the amendment in spite of the deadline, leaving just one more state needed to meet the threshold. Now advocates like Coberly, along with a bipartisan group of lawmakers on Capitol Hill, are working to ensure the amendment will be added to the Constitution once the final state ratifies it.

CC: Linda, thanks so much for joining me today.

Linda Coberly: Good morning. I’m very happy to be with you.

CC: Linda, tell us about the ERA coalition’s legal task force, and when did you get involved?

LC: So, the ERA coalition is an organization that exists to advocate for Constitutional protection for women, and it is an organization that’s been around for a little while and it advocates both for a federal ERA and for state ERAs. A lot of people don’t realize that many states have their own Equal Rights Amendments in their state constitutions, and the ERA coalition works towards ratification of ERAs in states as well. I got involved with the ERA coalition following work that I and my firm did on the Equal Rights Amendment here in Illinois. I’m from Chicago, and you may know that the ERA died in Illinois in 1982, or I’d rather not say died, because it isn’t over yet. We have more work to do. But that was really the end of the road in the initial effort to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.

I personally got involved through my law firm. I’m a partner at Winston and Strawn in Chicago, which is a very old firm here in the city. And our chairman actually heard a story on NPR, a couple of years ago, about the Equal Rights Amendment ratification effort in Nevada, and was very surprised to hear that Nevada had ratified after decades of inactivity by legislatures on the Equal Rights Amendment And he actually called me to his office and he said, “I need to talk to you about the Equal Rights Amendment,” which I must say, I found a surprising topic that morning in his office. But he said, “We really should get involved in this, because Illinois hasn’t ratified yet.” So we convened a group of lawyers at our firm to work on ratification, beginning with understanding what the status was. And then we got involved with the grassroots efforts that were working in Illinois to, to advance ratification. And we did a number of things to help educate people about what it is, and about what the legal issues are. Because we found that at least from our perspective, at that time, in this state, there weren’t very many people doing the legal work to analyze and educate about what impact the ERA could have, and what the issues were related to ratification at this time.

I was just thrilled when the Equal Rights Amendment was ratified in Illinois last year. So, since then we’ve been working with our colleagues at my firm in North Carolina, on the effort to ratify there. With our colleagues in Washington, D.C. on the effort to ratify in Virginia. And as a result of my work and my testimony, actually, I got a call from the National ERA coalition, who had been watching all of this very closely and was involved behind the scenes. And they invited me to get involved in the national coalition. Our firm actually joined as one of the lead organizations for the coalition, and I was asked to be the head of the legal task force. And the function of the legal task force is to bring together some of the legal task force is to bring together some of the best constitutional scholars around, and to talk about what kinds of issues might come up, to answer questions, to analyze legal strategy, and the constitutionality of a ratification at this time. The members of the coalition task force include Katherine McKinnon, who was actually a law professor of mine and a very prominent scholar in feminist theory. And Kathleen Sullivan, who is the dean of Stanford Law School. And Erwin Chemerinsky, who literally wrote the book on federal procedure and federal courts and is a very prominent constitutional scholar. Along with a number of other people, including Jessica Newarth, who was a very important part of the ratification effort in the ’70s. So what we do is convene conversation — raise questions, we’ve done some written pieces to talk about the legal issues.

CC: Now, you mentioned states have separate ERAs. How many states do?

LC: That’s an excellent question. And I don’t know off the top of my head. What I can tell you is that Illinois did have a state ERA, and had a state ERA in place dating back to the ratification of its own constitution, which is actually pretty recent, in the ’70s. And, and yet Illinois didn’t ratify the federal ERA when it had the opportunity in the ’70s and early ’80s. And I think one of the reasons was that the issue became quite politicized. There was actually kind of a rush by states across the nation to ratify as soon as Congress actually approved and sent the ERA for ratification to the states and that was in 1972. So 22 states ratified very quickly, and then the opposition as more mobilized and led by Phyllis Schlafly, and in Illinois it became, by the end of the ’70s, a very hot issue. It was still at a time when it was somewhat controversial for women to be in the workforce, so some of the talking points against the ERA in the ’70s and early ’80s don’t even make sense anymore based on where we are as a culture. And that’s one of the challenges, I think, for us today, is to think about the ERA in a, in a contemporary context.

CC: And are there any contemporary opposition voices at this point?

LC: There are. It’s a small group. Studies done by the ERA coalition show that the overwhelming majority of Americans think that there should be a constitutional equality guarantee. And in fact, many people think it already exists and they’re just not well informed about that topic. There is some opposition today. Some of the opposition actually attempts to pull the talking points from the Phyllis Schlafly era into today, and for example, you hear sometimes opponents of the ERA who, again, are a distinct and small minority, talking about how passing the ERA would eliminate protections for women that exist in the law today. And that’s similar to talking points that were used in the ’70s and early ’80s, and it’s just not true.

CC: OK. So, walk us through what was going on with the ERA between 1982 and 2017. Do you have any inclination about what spurred Nevada to kind of reinvigorate this whole matter?

LC: Well, I do. And I think, one thing to remember is that this actually has been going on all this time. So it’s, it’s not as if the effort to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment came completely out of the blue. It was just under the radar screen a bit. In many states including Illinois, a bill was introduced almost every year to ratify, of the last 20 years. At least. And in fact, the proponent, the principle sponsor of the ERA in Illinois, was somebody who had continually introduced the ERA for ratification over the years. There wasn’t a lot of grassroots support. And the national ERA coalition predates 2017 as well. And so that’s an organization that’s been working in a lot of different respects to work toward constitutional equality. So the work has been going on in the federal system.

Carolyn Maloney in Congress has introduced the Equal Rights Amendment anew every year for many, many years. And what’s different today is that now she’s also the co-sponsor of a bill that would also eliminate the deadline that expired in 1982 on the Equal Rights Amendment that was introduced in 1972. So, the effort to kind of restart the ERA conversation has been in play in Congress for decades, but the removal of the deadline is kind of a new idea. And that’s what was really spurred by what happened in Nevada. In Nevada, state senator Pat Spearman really led the charge to have the Equal Rights Amendment ratified. And I think what really made the difference in 2017 was the Women’s March, and a new sense after the 2016 election that the gains that have been fought for all this time in terms of gender protection and equality are not secure. And I believe that’s what really changed the conversation and created the kind of grassroots support that was needed to get the ratification in Nevada and in Illinois.

So in Illinois there had always been a sponsor, but unless you have grassroots support — you know, people calling their legislators, people writing, people doing op-eds and blog posts and really kind of pounding the pavement on the issue — it’s just not going to work. And so it was really the, I think, the Women’s March that brought together a lot of these disparate organizations and mobilized them to move the conversation forward. There’s a bill pending in both the House and the Senate to remove the deadline and eliminate any potential barrier to ratification at this time.

CC: The deadline is somewhat arbitrary, isn’t that correct?

LC: It is. It’s actually something that, that is kind of a new phenomenon in the 20th century. The constitution can be amended based on a process described in Article 5, and it was that process that led to the adoption of the Bill of Rights, for example. And there’s nothing in Article 5 of the constitution that talks about a time limit. And the amendments in the early part of our nation’s history, including the 14th Amendment, including the anti-slavery amendment, including, you know, a variety of amendments, were introduced in Congress and sent to the states for ratification without any deadline. That was not a thing. In the 20th century, and actually specifically with the prohibition amendment, Congress began to look at imposing deadlines on the ratification of amendments. And it was really for political reasons. But most of the amendments that were introduced in the 20th century had a deadline of seven years. One of the principles in our constitutional system is that a Congress cannot bind future Congresses. So if the Congress who’s sitting today wishes to eliminate that deadline, it can do so. It can just repeal the deadline. And that’s what we’re working toward in the House and the Senate right now.

CC: I see now. OK. So last year, Virginia came pretty close to being the final state. What happened there, and which states are you holding your hopes for in the coming year?

LC: Well, in Virginia it was a, it was a very interesting situation. The bill for ratification couldn’t make it out of committee, because it was blocked by the chair of the committee, who was an opponent. And that’s unfortunate because it’s almost certainly the case that there would have been enough votes in the chamber itself to pass the bill, to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment. And that’s partly because, remember, this is actually a bipartisan effort. And it’s only the far right of the Republican party that opposes the Equal Rights Amendment. In Nevada and in Illinois, there was, in the end, was bipartisan support for passing the Equal Rights Amendment. So, in Virginia it was held up by the chair of the relevant committee. And there was actually a procedural vote to bypass, to get the bill to the chamber despite the opposition of the chair. And that procedural vote failed by one vote. I think it’s very likely that there will be sufficient changes in the Virginia legislature in the upcoming election to lay the groundwork for ratification in Virginia in the beginning of 2020. But there are other states who are close on Virginia’s heels. North Carolina is very close and has a, a very well-developed grassroots movement. The National Coalition is involved but as with all politics it only works if people on the ground in that state really support it, and there’s a very active movement in North Carolina to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment. And in fact, there are active ratification efforts in all of the unratified states, in every single one. Arizona, Florida, even Utah have made moves in favor of ratification, and there are people working on the ground in each of those states.

CC: So, let’s say the final state ratifies. What happens next in your, in your imagination?

LC: That’s a very interesting question. In part it depends on whether the deadline is still in place.

CC: Let’s say it is.

LC: If it is, then I think there could be litigation. There are some who argue that the deadline is not effective to stop the efficacy of an amendment, so the Supreme Court has already held that Congress has the power to impose a deadline if it wants to. It can, you know, that’s something that it can do as part of its work in proposing an amendment to the states. And it held that back in the ’20s, but that’s never really been tested. The efficacy of a deadline like that has never really been tested, and it would seem strange if a statement by Congress in 1972 could stand in the way of an amendment that has been ratified by three-quarters of the states. So, that’s one thing that could happen. I think another thing that will, will certainly happen is increased efforts, and increased momentum, relating to the bills that are pending in Congress to remove the deadline. Because once three-quarters of the states have expressed a desire to have the amendment be part of the constitution, I think there would be a tremendous amount of pressure on Congress to eliminate this barrier, this potential barrier, to the effectiveness of the amendment.

CC: And if they didn’t, would it just sort of float around out there, and Congress would continue to try to remove the deadline?

LC: Well, I think it could. And this is why the, the ratification efforts in Congress, the effort to get the deadline removed, are important. Because if the deadline isn’t removed, then the efficacy of the Equal Rights Amendment would have to be resolved in court. And that could be a very long process. It could go on for years. It’s, you know, the Supreme Court doesn’t necessarily take cases the first time. It’s something that might need to kick around in a variety of courts until disagreement developed and then the Supreme Court would get involved. So it could be a very, very, very long process. Removing the deadline would eliminate that fight, or could eliminate that fight, and would express a contemporary view by Congress that this is something that should become part of the Constitution. Now there might still be a legal fight. Some opponents of the Equal Rights Amendment might still try to argue that the deadline can’t be eliminated retroactively. There were a couple of states — five, actually — who attempted to take back their ratification back in the 1970s.

CC: I wondered that, yeah. That’s not a thing?

LC: It’s not a thing. So on this issue, we actually have some pretty good historical precedent The 14th amendment actually was made part of the constitution at a time when two of the states that had voted to ratify the 14th amendment had later tried to take it back. And yet everyone agreed, all three branches of the federal government, agreed that that the 14th amendment was appropriately ratified and we all know it’s part of the Constitution today. So, there’s good historical precedent for this and it makes sense, because a ratification is different than a law that a legislature adopts, that it would have to renew and continue to keep in effect and extend and all that kind of stuff. A ratification is something that happens at a moment in time, and the question under Article 5 is simply whether the legislature of the state has ratified. And so for those five states, the answer to that question is yes. There has been a ratification, and it’s not something that can be taken back.

CC: OK. So, back to imagining possible outcomes, let’s say the final state ratifies. The deadline is removed. What can women expect to come from the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment five, 10 years later?

LC: Well the Equal Rights Amendment will do a couple of things that are important. And first of all, just to lay the groundwork, Constitutional amendments are different than laws in that they’re not designed to have you know, immediate specific technical impact. They’re broader principles. And the impact of any Constitutional amendment is something that’s ultimately resolved in courts and in lawmaking. So for the Equal Rights Amendment it would do two important things. One is, it would constitutionalize, for the very first time, an equality principle for the sexes. It would make clear in our governing document, the document that describes our government and the rights we all have vis-à-vis the government, that discrimination on the basis of sex is unlawful. Now, like with any constitutional protection, that’s not an unlimited proposition. I mean, every constitutional right has limits, even the First Amendment. There are certain things that the government can do to limit people’s speech rights. So, so the same would be true of the Constitutional Equality Principle. But it would provide an additional tool for women and men to challenge discrimination on the basis of sex, and it would elevate that kind of discrimination to the same level of illegitimacy that applies to race and discrimination on the basis of religion and that sort of thing.

Under the current Supreme Court cases, the 14th Amendment provides some protection against discrimination on the basis of sex, but not as much protection as it provides to other kinds of discrimination. Conservative justices, including the late Justice Scalia, believed that the 14th Amendment shouldn’t provide any protection on the basis of sex, because that’s not what people were thinking about when they passed it. And that’s certainly true, right? I mean, the 14th Amendment was passed at a time when women didn’t even have the right to vote. I’m sure it’s true that nobody thought, when the Equal Rights Amendment -- or, when the 14th Amendment was being passed, that it would prevent discrimination on the basis of sex, when that was a fundamental part of our culture at that time. But that’s not how the Constitution works. It’s a principle that then is applied in different contexts and settings, and we now know that discrimination on the basis of sex is something that should be treated with the same seriousness.

The Equal Rights Amendment would eliminate any argument that the Constitution doesn’t really talk about sex discrimination. So for conservative justices who actually may be interested in rolling back the existing protections, under the 14th Amendment, the Equal Rights Amendment would put a stop to that. It would also provide an additional tool against discrimination that exists under our current laws. For example, in law enforcement. Law enforcement practices. The military. Some kinds of government employment. There are already some protections in the laws and statues against that kind of discrimination, but statues can be changed pretty easily. And then there’s one other very important thing it would do. Which is the second clause of the Equal Rights Amendment actually empowers congress to enact laws that are designed to further the right embodied in the first clause. So the first clause is the that you’ve quoted. Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” The second clause empowers Congress to do something about that. And that’s important because right now, most of the time when Congress acts, it acts based on power given to it under the commerce clause of the Constitution. So Congress has no power other than what the Constitution gives it. All the other powers are reserved to the states. But the Constitution gives Congress the power to legislate in the area of interstate commerce, and so most of what Congress does is under that power. But sometimes what Congress wants to do, and what the political will asks Congress to do, goes pretty far beyond the commerce power. And so you sometimes see lawsuits that challenge acts of Congress as too far afield from commerce, and that was the case with a law passed by Congress to criminalize female genital mutilation, or circumcision. There was a doctor who was convicted under that statute, and just last year a federal judge in Michigan held that the federal statue was unconstitutional, because it was not sufficiently connected with the power of Congress under the existing Constitution. Now, lots of people think that decision was wrong and we can have a separate conversation about that, but the Equal Rights Amendment would provide an alternative source of power for Congress to pass that kind of law.

CC: What do you think it says about us as society that this has been such a protracted battle?

LC: It’s pretty stunning, isn’t it? And every constitution created since World War II has an Equal Rights Amendment in it.

CC: I wanted to ask how we stack up against other socially liberal countries.

LC: Very poorly. In fact, the only ones who don’t are, are countries that we would not describe as liberal. And you know, I think it’s a reflection of the divisiveness of our politics. In some pockets of our culture, there remains a deep-seated view that it’s just OK to treat women differently. And so when push comes to shove, the question we face is whether it’s time to put those kinds of justifications for discrimination to bed.

CC: Well, thank you so much for this conversation, Linda. I really appreciate you making the time for us today.

LC: It’s been a real pleasure to be with you. Thank you so much.

CC: Thanks.

Paw in print

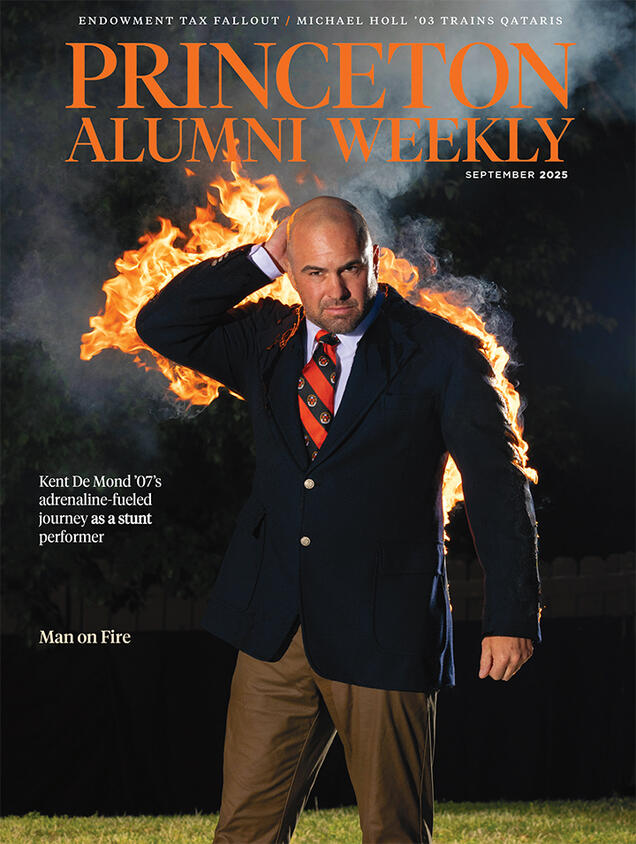

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

No responses yet