PAWcast: Professor Nell Irvin Painter on Being ‘Old in Art School’

The takeaway? “Do not see yourself through other people’s eyes.”

Nell Irvin Painter, a Princeton professor emerita of history, was 67 years old when she enrolled as an MFA student at the Rhode Island School of Design. During her second year there her book The History of White People was released and would become a New York Times bestseller. It was disorienting event, as she describes it. On one hand, there was the elation of receiving laudatory reviews, and on the other, the ever-present, stinging criticisms she experienced in art school, which she calls “one long tearing down.”

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

Her latest book, Old in Art School (Counterpoint Press), describes her late-in-life journey from preeminent historian to painter. She began her art-school education with a BFA at age 64 from the Mason Gross School of Art at Rutgers-New Brunswick before moving on to RISD. Her memoir describes her delight in acquiring new habits and artistic skills, the growing pains as her artistic sensibilities changed, and the challenges of balancing it all while juggling her obligations to her ailing parents on the West Coast.

This is part of a monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students.

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: Hello, and welcome to Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast, a monthly Q&A show with various members of the Princeton community. I’m Carrie Compton, and this month I spoke with Nell Irvin Painter, Princeton professor emerita of history, who was 67 years old when she enrolled as an MFA student at the Rhode Island School of Design. During her second year there her book, The History of White People was released and would become a New York Times bestseller. It was disorienting event, as she describes it. On one hand, there was the elation of receiving a laudatory review on the front page of the New York Times Review of Books, and on the other, the ever-present, stinging criticisms she experienced in art school, which she calls “one long tearing down.”

Her latest book, Old in Art School, describes her late-in-life journey from preeminent historian to painter. She began her art-school education with a BFA at age 64 from the Mason Gross School of Art at Rutgers-New Brunswick before moving on to RISD. Her memoir describes her delight in acquiring new habits and artistic skills, the growing pains as her artistic sensibilities changed, and the challenges of balancing it all while juggling her obligations to her ailing parents on the West Coast. Painter and I met in her basement art studio in Newark, New Jersey, which, fair warning, is sometimes noisy.

CC: Let’s start with your decision to pursue art.

Nell Painter: Yeah.

CC: You were 64 years old.

NP: Yeah.

CC: And a prominent historian with many professional accolades under your belt. Then you decide to not just do art in your free time, but to enroll in art school.

NP: Yeah. Yeah.

CC: Why?

NP: Why? Well, there’s two parts to that question; the first part is, why art? And that was that eye, you know, sort of looking at stuff. I had been an art major briefly at Berkeley when I was an undergraduate in the ‘60s. So and my father taught me to draw, and I drew all the time when I was a kid. People have asked me: did I want to be an artist when I grew up? And I don’t think I thought that far ahead. I’m not a thinker far ahead. I go, like, from here, to there, to there, to there, to there, to — that’s how I do it. But I’ve always been drawn to imagery, to color, to pattern, to texture. I’m a knitter. I have always been attracted to the visual. And my history writing, Sojourner Truth in particular. And then thinking about The History of White People, that was as I was in art school and realizing how important the visual was in how scientists thought about, or theorized race. So art came to me from a long time ago, from knitting, and from scholarship. Now, that’s the art part.

The second part is, why go to art school? I was saying to my friends, “You know, I’m really thinking about doing something different, doing art.”

And my friends said, “Well, you’ve got all these degrees already, you’ve got a PhD from Harvard. You don’t need another degree.” And It’s true, I didn’t need another degree. At that time, the Newark Museum had a program which got cut in their financial problems, where you could take classes. So I took a pastel class, because I had never used pastels, it seemed interesting. The guy was really nice. And he knew what he was doing. But I discovered that that aesthetic, that memetic, verisimilitude, make something so like what it is, that you could taste it, or you could touch it — it’s not what I wanted. I didn’t realize that until I was in the class. That helped me understand how I wanted to see, and how I wanted to relate my hand to my art. So OK, not just taking the occasional class. I took the Drawing and Painting Marathon at the Studio School in New York; highly respected, very intense. I wanted to know if I could get up at 6:30 in the morning, go over to A Street, stand up drawing and painting for eight hours, wolf down some dinner, have a crit, and then come back to Newark and then do the same thing the next day, five days a week, for five weeks. Yeah, I could. And I really liked it. I really, really liked it. But the problem with the Studio School, it’s a studio school. And that made me see that I wanted the intellectual context, the intellectual infrastructure of art as well. I wanted art history. I wanted art criticism. I wanted artists talking back and forth, and people whose work it is to look at art and think about it, to talk about it. So that’s how I ended up going to Mason Gross for the BFA. And I don’t know if I originally wanted to go to graduate school, but I pretty soon realized I wanted to go to graduate school, because I wanted to work harder than the kids did. I wanted to be more intense than the kids. I thought graduate school would do that, which it did.

CC: Talk about when you are at Mason Gross, you make a very interesting discovery. You say that you discovered that your chief vulnerability of being old and at art school has nothing to do with gender, age, or race, but your “lying 20th century eyes.”

NP: Lying 20th century eyes. Yeah!

CC: Talk about what that means.

NP: I have no idea. Because art is supposed to be like science, for everybody, for all time. And I have not grown up in an intensely art-centered home, but my father, his hobby was woodworking. And my father taught me how to draw. So, I mean, I had seen things. We had a few books around, and when I was in high school, I was in art club, with, you know, so that was fine. I thought that that art would just carry over into now art. Well, it doesn’t, because just like the scholarship — I hate to use the word “fashion,” but that is the word — fashions change. The questions change. The mediums change. And the viewers change. So what I brought with me from the 20th century hardly served in the 21st.

NP: Appropriation is a perfect way — it’s a totally acceptable way of making art now. You take something off the web. You take some other artist’s strategy or composition or color. A couple of days ago, I went to the Charline von Heyl show, which his fantastic. And I took pictures, close up, because of her use of pattern. I’m going to steal that. I’m going to use that — fine. But for a historian and for my 20th-century eyes, which prized invention, originality — that didn’t do — that was using somebody else’s stuff. And I still do it hesitantly.

CC: Another thing that you talk about in the book that I think is really interesting is these notions of truth.

NP: Yeah.

CC: We’re in an era, as you well know, where the truth is being somewhat abused in day-to-day discourse.

NP: Yeah.

CC: But as a historian, you actually sought out art as an escape from truth.

NP: As a historian, I was always very careful. Like the book I did before The History of White People, it has, like, 100 pages of end notes of saying, “This is where that came from. This is where that came from. This is where that came from.” So as a historian, I couldn’t ignore the archive. As a historian, I couldn’t lie about what was in the archive. If there is something that I didn’t want to see in the archive, I couldn’t suppress it. If there was something I needed from the archive that wasn’t there, I couldn’t make it up. Now I can.

CC: So generally speaking, what would you say — how do you describe being old in art school? Why do you think your age in particular ended up carrying so much significance in that experience?

NP: Yeah. Let me take the second question first. Our society is in love with youth. Art worlds are just squared that much. The art world is besotted by youth. So people — gallerists were coming to my fellow students, and snooping around. I mean, it’s really — it happens at Yale all the time, and it happened somewhat at RISD, that the hot new thing — and we were trained to be hot, young artists. And I realized, I don’t think I’ll ever be hot, but I certainly won’t be young! (laughter) Yeah. The big thing was that the art world was so youth-centered. I was on a program last night in which we talked about age and creativity. And one of the people in the audience says, “It’s like if you’re a woman artist, you can be ‘hot’ — that is to say ‘popular’ — when you’re in your 20s, and again when you’re 95. But in between, you’re invisible.”

CC: Mmm. Interesting.

NP: Yeah.

CC: OK. So you graduate with your BFA from Mason Gross.

NP: Yeah.

CC: Then you decided to enroll in Rhode Island School of Design for an MFA.

NP: Yeah.

CC: You say in hindsight that this was a mistake.

NP: It was a big mistake.

I realized as I was writing, I didn’t think of it as a chapter called “A Bad Decision” until I was well into writing it, and sort of getting into my own head. That’s the beauty of writing, just keeping at it, and learning things. My mother started her descent into mortal illness at the end of the summer of 2008. So during the academic year 2008-2009, I was going back and forth and back and forth. And I had the feeling that I didn’t have any time. You know, at this point, what was I, 64, 66 … something like 66, 67. I’m thinking, oh, my time is so short, my time is – and I told myself “I’ve got to do this now. I’ve got to do this now.” I remember one of my mentors, the much-lamented late Denise Tomaso said, “You can apply now, and if you don’t get in, you can apply next year. Or, if you get into one but not where you really want to go, if you go to the first one, then you can go to the next one the next year.” I thought, “I don’t have time for that!” As I was writing — I realized, hold on a minute. You just ask anybody. You just ask Google, should you make an important decision when your mother’s dying? And Google will say, “Of course not!” Of course not. So that’s the big thing. Now, I mean, my mother’s long dead, my father is two years dead, I feel like I have all the time in the world. And if I were in that position now, I would take another year at Mason Gross, and maybe I would make art for a while, and figure myself out better as an artist, then really be able to — I mean, I would be, like, 80. (laughter) I would be able to really make use of graduate school. But then again, would graduate school accept an 80-year-old applicant?

CC: Do you feel like you weren’t ready?

NP: In some ways, I wasn’t ready. I could have used another year of preparation. But then again, that preparation would have made me more the 20th century artist, I would have had more skills. But skills were downgraded. So in a way, it would have made me less of a 21st century artist. Plus my big handicap is being old. And I would have just been older. On the one hand, it was a bad decision, but on the other hand, it was OK. And on the third hand, I did survive. And I don’t think I would have been any less pathetic if I had had better skills, or been in New York longer or been older. I would have been just as pathetic, because the experience of graduate art school is so patheticizing.

CC: Hmm. In what way?

NP: Emma Amos told me when I was at the Studio School, you know, way before I went to Mason Gross, she said, “Graduate art school is just one long tearing down.”

CC: Really?

NP: Yeah. And I have talked to people who have done creative writing MFAs, whether for nonfiction, fiction, poetry, whatever — and their stories match mine, especially if they’re black women. Graduate schools are notoriously white and white-centered. So for writing, for instance, what kind of writing do our professors tending to want — it’s the little stuff, it’s the everyday, it’s walking down your street in Brooklyn. Not something dramatic like, say, having to deal with racism or sexism or poverty, or whatever, that is so much a part of the rest of us. So I would bet that a white student, or white woman from a working class background would feel some of the same kind of alienation I felt back on class grounds. My class background was pretty — I mean, I was not as rich. I mean, I was at RISD with some people who were much wealthier than I. And I’m not poor. I mean, I can afford to go to RISD.

CC: Sure. Right, yeah. So do you consider yourself a 21st century artist now?

NP: Yeah. Yeah.

CC: Has your taste changed? Have you almost cast off some of your old favorites, for new?

NP: Yeah, definitely. Definitely.

CC: What’s an example?

NP: Let’s see — oh yeah, yeah, yeah. R. B. Kitaj, who was a virtuoso painter, was one of my favorites when I was an undergraduate. And I mentioned him in my book. He wrote this cockamamie — what’s it called — the — it’s got “Jewish” in it, which is part of what got him in trouble as a painter.

CC: Ah.

NP: Because he painted as a Jewish painter, which was not to be done.

But anyway, I used to love his painting, figurative painting. Virtuoso painting. And I don’t like it anymore.

I mean, it’s OK, and I admired the technique. But he’s no longer one of my very favorite painters.

CC: Hmm. So talk about how you work and how often you work nowadays.

NP: Yeah. On Wednesday, I’m going to talk to my literary agent and I’m going to tell her that I want to make an artist’s book about Emmett Till, and how I’ve experienced the thing of Emmett Till’s murder over time. And I want to make an artist’s book in which I draw all the images, heavier on the images than on text, or maybe 50/50. I didn’t know that’s what I wanted to do, at first. But the question is time. What do I use my time for? So I don’t have as much time to make art. I love printmaking. I probably should have been a printmaker, because I work in series.

CC: What have been some of the most memorable reactions to your book?

NP: For me, the very different ways that people respond to it. So one of my first book events was in San Alcala with a painter friend, Frank Howling. What Frank talked about was my use of artist colors to talk about color.

CC: Yeah. I liked that.

NP: Yeah. People with an art background are likely to like that. Other people really appreciated my honesty about my parents, even my anger with my father. Just admitting that my father was depressed, and talking about some of his rants and his imaginings. So that part, I remember in Seattle, I remember in the audience, because, you know, the book starts with, “You’ll never be an artist.” And my immediate response to Henry is, “Henry, that’s bullshit.” Then as you go through, you discover that I turn into this pathetic mess. She said, “Why couldn’t you keep that confidence of, ‘Henry, that’s bullshit’ throughout?” And I said, “I just couldn’t.” And the audience applauded.

CC: Right.

NP: They loved the honesty of weakness, you might say. So different readers get glom on to different parts. I’ve had several people write to me in their 60s, in their 80s, in their 70s, saying that they went back to art school at an advanced age — which could be anything from 32 to in your 60s, and telling me about their experience. And very often — mostly saying they recognized what I’ve said.

CC: Yeah. Speaking of Henry and the harsh words he had for you —

NP: Yes?

CC: — this was an instructor of yours who told you you would never be an artist, try as you might?

NP: Yes?

CC: Have you ever —

NP: And trying was a fault of mine.

CC: Right.

NP: Yeah.

CC: Right. Have you heard from him?

NP: No. I haven’t heard. I’ve heard from Stephen Westfall, my painting teacher at Mason Gross, who really likes the book.

But the others have not said anything. Oh, and I have my friend teacher, who was my friend teacher at the time, Deborah Balken, you know, we’ve been friends throughout, so, yeah. But the man who’s the head of the board of trustees is a big fan of the book. I’m going to go back to RISD in the spring, and the administrator, newly-hired administrator for diversity and Deborah, my criticism teacher, we will talk. Then the head of the trustee board, Michael Spalter, will have a reception for me. So he is the official embrace of RISD, even if the faculty is not so sure.

CC: Do you have anything that we didn’t talk about that you want to add?

NP: Yeah. One thing, which is at the end of the book.

CC: Yeah?

NP: Do not see yourself through other people’s eyes. I have had several people tell me that that — men, too — that that is really, really good advice. It’s so simple. But it’s hard won. And it’s hard to keep at it. It’s hard to keep inside yourself and not be crushed by what society thinks of you as an older person, as a woman, as an old woman, as an old black woman, as a black woman, as a dark-skinned, black woman. There’s just so much in here that either says “no,” or, “you’re wrong,” or, “your’re not here.” So that’s one thing. Another thing is — and I say, I think, at some point in the book, that I would like old people to be able to say, as black people say about black — “Say it loud. I’m old, and I’m proud.” And I have actually done that with some of my audiences, and people love it. Even people who are not old. And I start them by saying, “Say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud.” And white people get a kick out of that, too. It feels very liberating, they say. But so that’s one thing you can see, to be able to say, “I’m old and I’m proud,” to embrace old. Then when I realized why it’s so hard to embrace old, it’s that old people, as normal people, are still invisible in our visible culture, our visual culture. So for instance, then to go to the parallel with black, when I grew up, I never saw black people represented. And if a black person was represented, it was, like, a big deal. And then it got so a black person could be represented as a black person. And then, around 2000, black people, or actors, or whatever, could be represented just as “people.” So now, in advertisements for fancy cars, there’ll be a black person driving it. Not as a “black person” — well, sort of, that there are some connotations to a cool-looking black person. But driving the car as a person. Now I see old people as old people. Let me sell you some adult diapers. But not so much just as people. That’s what I would like to see.

CC: Fair enough. Thank you.

Thanks so much for listening to this month’s PAWcast. If you’d like to hear other episodes, please go to paw.princeton.edu or subscribe on Apple iTunes. Till next time.

Paw in print

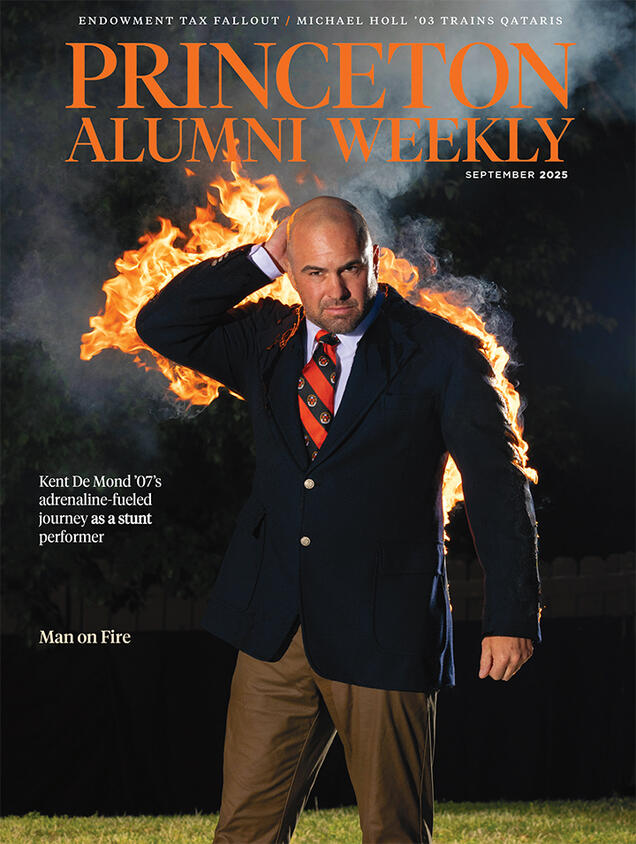

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

No responses yet