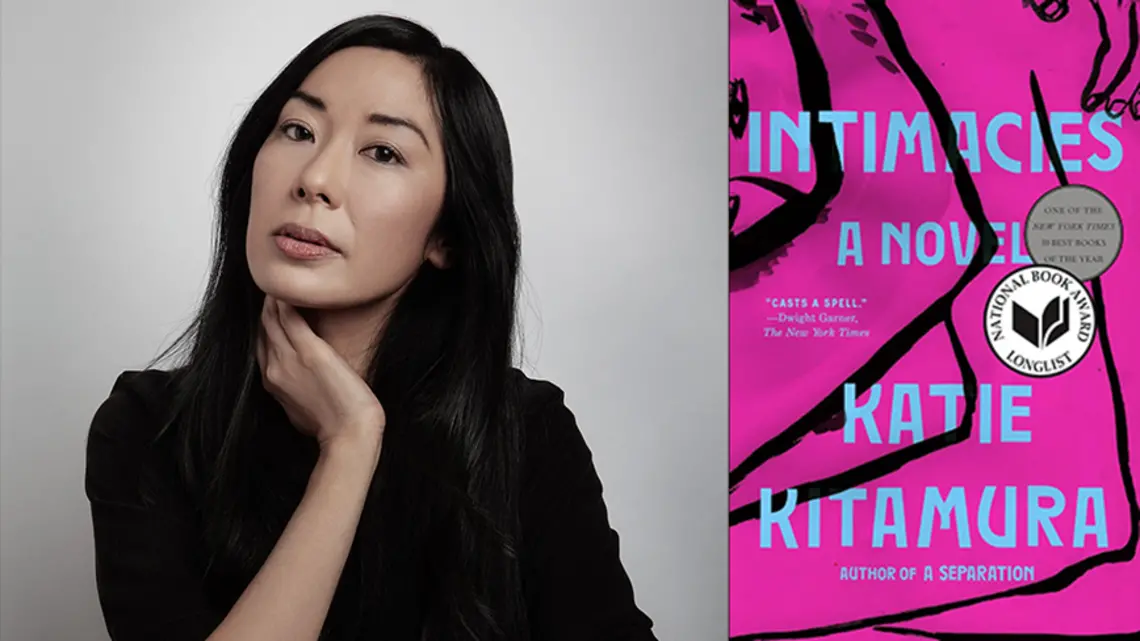

‘Intimacies’ by Katie Kitamura ’99

‘I don’t know that we can always be reduced to events that have happened in our past …. I’m very much interested in the way that characters behave in the present’

On this episode of the PAW Book Club podcast, we talk with Katie Kitamura ’99 about her novel Intimacies. She answered our questions about the book, discussing why she gives so little backstory to her characters and why readers’ strong dislike of one character surprised her. She also discussed her writing philosophy and what advice she gives as a creative writing professor at NYU. “The writing itself, when it is private, when it’s just myself, when I can do whatever I want, that is the most special part of writing to me,” she said. “That’s my favorite part.”

Join the PAW Book Club here, and get started on our next read, Jodi Picoult ’87’s By Any Other Name.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

I’m Liz Daugherty and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s Book Club Podcast, where Princeton alumni read a book together.

Today I’m excited to speak with Katie Kitamura from the Class of ’99 about her much lauded novel, Intimacies. The story follows a woman who comes to The Hague as an interpreter for the international court and begins to interpret for a former president who’s facing war crime charges. Meanwhile, in her personal life, she begins dating a man who’s separated from his wife, and she begins to get drawn into a family recently touched by a seemingly random act of violence. A New York Times reviewer said the book is “coolly written and casts a spell,” and added that, “One of Kitamura’s gifts is inject every scene with a pinprick of dread.”

So Katie, thank you so much for talking with me today and for participating in our book club. I’ve gathered a bunch of great questions from our book club members, so I’m going to start and we’ll just rock and roll.

KK: Thank you for having me. I’m really thrilled to be doing this.

LD: So Julie Meyers from the Class of 1992 asked, “How did your experiences with different cultures and languages influence the themes and characters in Intimacies?”

KK: Oh, that’s such an interesting question. I always find it really interesting writing a book because often I think it’s about one thing and it’s only after I’ve finished it, after it’s been published and out in the world that I realized what it’s really about. And I don’t think when I started writing the book, which is about a simultaneous interpreter working in The Hague, in the Netherlands, I thought it had any relationship at all to my life. I am embarrassingly monolingual, I understand and spoke Japanese as a child, I have a little bit of French, but really I am by no means a kind of multilingual person as a character in the novel is.

But it was only after I published the book that I realized that I grew up in a bilingual household for many, many years. I really was almost an interpreter within my family. My parents spoke fluent English maybe only once I was a teenager. So for that early period of my life, I was often the person in the household who spoke the most fluent English.

And so there was an interesting way in which as a first generation, second generation immigrant, I was a person who was acting as an interpreter for my family, a kind of experience that I think is not at all uncommon and that in many ways fed into the book, I think, in terms of the sense of not being firmly oriented towards a single culture, which is very much how the central character is, but also in the fundamental relationship to language, to this sense that there are things that can be said in one language, for example, that can’t be said in another language, the sense that there are gaps between languages, but there are also things that can be added in translation. Those are kind of the themes that really preoccupy me in my fiction, and those are very much from the very earliest years of my life.

LD: So Laura Redman, Class of 2003, asked — and that’s interesting, you just talked about what you brought to the book, now she’s asking what you did when you were preparing for it — she said, “Your descriptions of The Hague trial are so detailed. Did you spend a lot of time covering The Hague as a journalist or shadowing a trial to get the nuances right?”

KK: I mean, this was something I really, really wanted to get right. And I think an interesting thing about research is I think my natural inclinations as a person are to approach research almost in a kind of fact-checking way just to make sure I got everything right. But in fact, research at its most profound is really generative for a fiction writer. So I decided that I did need to go to The Hague and I sat in on the trial of Laurent Gbagbo, the former president of Côte d’Ivoire, for about, I think it was two weeks at the International Criminal Court, which is a court that the court in the novel is loosely based on. And I also interviewed quite a few of the interpreters who worked at the ICC. And that completely transformed my understanding of what the profession of an interpreter really was. I realized that it was highly performative.

It’s not enough just to kind of ferry the words and translate them into another language. You also need to kind of produce and communicate all the meaning that is contained outside of just language itself. I realized that the personalities were quite different to what I understood, and I also understood the degree to which they were operating under a great deal of psychological pressure. And so when I was interviewing these interpreters, one of them said something which really stayed with me and I think transformed the arc of the novel. And what he said was that he was working very closely with one person in particular, a person who had been accused of genocide, much like the character of my novel is. And over the course of working as an interpreter for this person, which in the case of a court like the ICC can be for several years, he developed a very close relationship with this person.

And he said that when he was found not guilty on what the interpreter believed was more of a technicality in the sense that he believed he had committed many of these things, he said he started crying from relief. And he felt that in that moment he had lost his moral standing and the moral ground beneath his feet had shifted completely through the work. And that was something that I thought was really interesting. This question of complicity, this question of how empathy is tied to complicity, those were the themes that I wanted to explore in the novel.

So in a sense, I did do quite a lot of research. I spent a lot of time in The Hague as a child. I attended this trial. I went through many, many transcripts. But I think getting things right is really, really important. But I think there was something else thematically at the core of the novel that I never would’ve reached if I hadn’t been able to do that research and if those people hadn’t been so generous in talking to me.

LD: So I thought this one was a really interesting question. Diana Silverman from the Class of 1987 said, “I was moved by your discussion of colonialism in the ICC. How could the court be more just?”

KK: How could it be more just? That’s a really interesting question. It’s something that I really grapple with. And it was interesting when the book came out, I think a lot of people read it as a critique of the ICC, which it was by no means intended to be. But I think I was interested in thinking as deeply as I was able about how the ICC functions as an institution or how any of these kinds of international justice courts function as institutions.

And I think one of the things, perhaps increasingly less so, but certainly still to a certain degree, I think people assume there’s a kind of impartiality to a court, that there’s an impartiality to the idea of justice and to the legal system. That is of course very, very far from true. And that there are biases that are in some ways built into these systems that are beyond individuals, I think.

And that is something that I really understood from my time looking at the ICC. It’s very much transparent even in the choice of languages. So the two official languages of the court are French and English, which are both colonial languages. And the vast majority, of course, of the cases that are tried, although that has recently begun to change, have been on the African continent on the whole, and that has only very recently changed.

How can that change? How can it become more just? It’s a many-headed beast, I think. A lot of the court’s activities have to do with jurisdiction. The United States famously does not recognize the ICC or the jury. It does not fall within the jurisdiction of the ICC. The question of who can be tried for crimes very much depends on who will sign their own statute, who will accept and recognize the ICC’s jurisdiction. So it is a kind of complicated thing that has to do not simply with the court, but with the way the court interfaces with governments and other institutional bodies around the world.

But I think one thing that is to me useful is to recognize that it is a system that has its own prejudices and biases built into it. And I think once you recognize those biases, then you’re part of the way there towards making concrete changes.

LD: That’s so interesting. Sometimes I think that fiction can bring you into a situation like that intimately, shall I say, because learning the facts of it can be shocking. But when you’re in it and you’re in the head of someone who’s experiencing it, which is what you can do with fiction, I don’t know, it brings it to life and hits home for people. You know what I mean? Do you ever feel that way about fiction?

KK: Well, yeah. I mean, one of the things is that I didn’t want to write a book that felt like a condemnation. The thing that seemed much more interesting to me was to write a character who begins to wonder if she’s in some way complicit because she’s part of this machine. That felt to me more interesting and kind of more ambiguous in a way, because to some extent she believes that she’s a kind of cog in the machine. She’s just an interpreter. She’s not a person who’s making big decisions.

But over the course of the novel, she begins to wonder, what does it mean to be part of this system? What does it mean to be somebody who is taking language, rendering it for the record of this institution that does have certain biases, for example. I think those are questions that are actually relevant to all of us. Very few of us will probably be involved in passing judgment on a war criminal, for example. But all of us belong to many, many different institutions, whether it’s the country we’re a citizen of or the university we went to or the place where we work. And just being able to understand what the relationship between the individual and the institution is, is something that I think, I mean, I agree with you. I think fiction is very, very good at doing that.

LD: So a few readers noticed that you don’t reveal much about the background of the character, that she’s Asian and how she looks, until close to the end of the book. So Rachel Vandagriff from the Class of 2005, she posed it I thought really well. She said, “You provide descriptions of many characters’ appearances, especially Jana, Adriaan, and Adriaan’s wife Gabby as well as the former president. But we learn very little about what the protagonist looks like. There’s one description of her in the taxi ride on the way to the deportation center that indicates she’s wearing a skirt. We learn that she’s not white, but only toward the end of the book, implied in her conversation with the accused president. Is that a purposeful authorial strategy? Could you say more about your choice to give us so much about the protagonist’s internal life while leaving so much to just a faint sketch?”

KK: Yeah, I’m fascinated by backstory and by the way we read backstory. So I often find there’s a kind of conventional narrative structure that you see sometimes in a novel where you have the setup in the first chapter and then the second chapter is like, “When, so-and-so was a child they grew up in” and they kind of give the backstory of the character. And as a reader of fiction, and I studied English at Princeton and then I went on to do a Ph.D. in American literature, you read that childhood information almost as a kind of key to understanding how the character is in the present day.

I think that’s very effective in a lot of ways. I think it gives the reader a lot of grounding, but I don’t know that it’s always necessarily true. I don’t know that we can always be reduced to events that have happened in our past. So I’m very much interested in the way that characters behave in the present. And I tend to take this gamble in my work that by immersing the reader into the point of view of the character so completely, that you almost can’t get out in a way that it is almost claustrophobic, I think. The necessity for backstory will fall away. And it’s of course a gamble because I think many times people do want to know things. They want to know where she spent her childhood and what her relationship with her parents was like, and when she had her first partner or whatever it might be.

I almost never do any of that, and I almost never know any of that when I’m writing my characters. I really discover my writers — my characters, I apologize — I discover my characters by being in scene with them and observing how they behave and kind of going a hundred percent into their point of view of seeing what they notice, seeing what they don’t notice, seeing how they interpret the world around them.

So she is attuned to people’s appearances, their charisma, their position, the way they exert themselves upon a certain social situation. So you get that observed very closely, but she’s much less adept at turning that observational skill inside internally onto herself. She’s somebody I think who moves through the world in a state of hyper attunement, but to some extent lacks a certain amount of self-knowledge. That kind of analytical eye is not always turned inward on her own behavior, on her own tendencies, her own frustrations, her own anger even. And so that is in a way, by withholding that, by showing her own lack of self-knowledge, her own inability to see herself, I hope is doing something and communicating something about the character herself.

LD: Diana Silverman, Class of ’87 asked, “Do you think about your character’s future lives? What do you think the protagonist will do for work and will she stay with Adriaan?”

KK: I love that question. I’m one of those writers, I have to say, I know the characters for the duration that they’re in the book, and then I don’t really know what happens after that. But in the case of this book, which is rare for me, I have to say I do think she stays with Adriaan. I think she does.

It was interesting when the book came out, the character who people had the strongest reaction to, very much to my surprise was Adriaan. I thought it would be perhaps the former president or even the protagonist herself, but in fact, the person who people seem to have the strongest feelings about was the kind of slightly errant and absent boyfriend. And so I think the question of what ... I think she does stay with him, the question of whether that’s a happy ending or a sad ending is I think another one entirely.

LD: Did you do that intentionally? Did you want people to react to him that way, or did it just sort of materialize?

KK: I think I wanted her to be put into a difficult situation, that is without question, and obviously he’s the person who is doing that to her. I really thought of it, and when the book came out, I first said this to I think my editor or my publicist, and they said, “Please don’t ever say that again.” And I said that to me, it’s really kind of like a middle-aged romance. It is a kind of relationship between two people who are, I think in love, but who are very, very pragmatic and who no longer expect total disclosure, full intimacy, all the kind of fantasies of what a relationship might look like when you’re much younger. Those fantasies have kind of bled away from these characters.

So in that sense, I thought it was not wonderful what he was doing, but I also thought it was understandable in some ways. He’s going through a separation from his partner, he has children. But I remember when my husband first read the novel, I can feel it, remember it very clearly in my head. He came to my office and he said, “He’s so awful to her, and why is he so awful to her?” So I think I underestimated the effect of his departure.

LD: Yeah, that’s too funny. OK, so more than one reader asked about your writing style, which was something that was noted very much in your many reviews of this book as well. Rachel Vandagriff, Class of 2005, called it, “Sentences that have extra clauses at the end that help the reader feel in the scene or in the thought.” And Sylvia Stevenson-Edelman, Class of 1976, described it like this, “There are so many kinds of intimacy in this book. Is the train of thought writing style a way of expressing the intimacy between the author and the reader?”

KK: Oh, that’s such a beautiful way of expressing it. But I think I do feel that the most intimate and important relationship in any book is the one between the reader and the writer. And the book is a kind of conduit for that relationship. And I really also think very much that the book is made in that relationship. The book changes depending on who is reading it, at what point in their life. When I read a book, it changes very much depending on when in my life I happened to have read it.

The book that I think about is actually a book I first read when I was in college, which is Portrait of a Lady by Henry James, which at that time I thought was a novel about a young woman making her way in the world. And then when I went back and visited it when I was kind of a bit older, I was like, “This is a devastating portrait of disappointment.” And so in that sense, I really do feel that books exist in a very brief and changeable and mutable way in the relationship between the reader and the writer.

And I think one thing that I wanted to do with the prose style is to convey not authority, but almost its opposite. So I think first person narrators, they often have a great deal of brio. They’re often kind of controlling the narrative. They’re telling a story, they understand the story, they’re shaping the reader’s perception. What I wanted to do was almost the opposite, I wanted to take the reader into the state of mind of somebody who doesn’t know what the narrative is, who isn’t sure what the story is, who exists in a state of uncertainty. And I wanted the novel to be almost like a transcript of the movement of one particular mind.

And so for example, one of the great inventions of first person in a way is that it’s somebody who’s speaking to you. And the vast majority of the time, the person who is speaking to you expresses a perfect metaphor on the first time, expresses everything beautifully at once. And I wanted to do the opposite. So the character often will say, “It could be A, or it could be B, or it could be C.” And there are often multiple attempts at expressing something.

And I think when I was a younger writer, my inclination was always to cut those back. But then when I kind of found this first person register, I actually thought, “Even if it’s not a beautiful sentence, even if it’s a sentence that is too long or is a little bit awkward, actually, if there’s some integrity to how it represents how a mind might work, then I want to keep that in the book.” So in a way, it is to me, I think, a kind of very intimate way of writing because it is letting the reader into the way the character actually is thinking with all of its kind of flaws and stupidities even at points. I mean, I wanted to keep all of that in the book.

LD: So Catherine Mallette, Class of 1984, she said, and tell me if you remember this, “During your visit to an Ohio boarding school, a student asked if you ever expected high school students would read your books. And you said, ‘I don’t imagine my books will be read by anybody.’” I don’t know if you remember this. She asked, “Could you share more of your thoughts on this?”

KK: Yeah, it would be within maybe the last, maybe even with Intimacies was the first time I thought, “Oh, somebody will read this book.” But writing to me is incredibly private. And I think in my life, I’m a partner. I have two small children. I’m a teacher. There are many, most of my life is taken up engaging with other people and not being alone. And the one time when I’m truly alone is when I’m writing fiction. And so to some extent, I have to do everything I can to preserve that sense of privacy, to believe that I can write whatever I want and to not think about what other people might think or to think about the judgment of other people. And that is what allows me to generate a draft.

Then when you’re editing, that’s when you to make this strange pivot, when you suddenly go from being the writer of your work to the reader of your work. And then that is when you really have to think about, “Am I giving enough to the reader? What will the reader’s experience be? Is this coherent? Am I giving them kind of footholds so that they can make their way through the material?” Then it really becomes an almost interesting, empathetic exercise into the mind of a new reader. But I think to me, the writing itself when it is private, when it’s just myself, when I can do whatever I want, that is the most special part of writing to me. That’s my favorite part.

LD: And finally, a couple of readers noticed that you moonlight as a creative writing professor at NYU. Yes?

KK: Yes, I do.

LD: And still find time for everything else. So Diana Silverman, Class of 1987, asks, “What advice do you give your creative writing students?” And parallel question Catherine Mallette, Class of ’84, wanted to know, “Are there any craft books you recommend to students or any particular pieces of fiction writing you think every creative writing student should read?”

KK: Those are both great questions. I do teach creative writing. I’ve been teaching on the MFA at NYU for I think about six or seven years, and it is really been an incredible experience to me. I think, as I indicated earlier, I’m very private in my writing. I never share it. I share a draft of my book when it is done, and I don’t share it before.

But my students, the writers in my workshop, they come in every week and they share 20 to 30 pages of new material that they’d just written with a group of 12 people. They accept all our feedback, and I think there’s something that they’re quite, it makes their writing quite robust. It makes it porous in a really interesting way. There’s a kind of strength that emerges from their willingness to be so open about their work that I find very, very inspiring. It’s actually changed to a certain extent the way I write, where I’ve been trying to kind of open up my writing practice a little bit more and send things to my editor earlier, just try to make it a little bit more malleable, which I do think is important.

I think the very basic, boring advice for people who are starting out writing is just to read all the time, to read widely, to read deeply, to read old things and to read new things, to understand the culture you’re writing into, but also understand the lineage and the history of how that culture came into being. I think that’s incredibly important.

At the moment, I’m doing a thing where I read something that is contemporary. I read something that was written in the 20th century, and then I try to read something that was written in the 19th century just so that I can keep a sense of flexibility of the relationship to language, which you can see changing so much depending on the period in which the books were written.

But I think a very personal piece of advice that I would give to anybody writing fiction is that fiction is about exposure. You have to reveal yourself in some way, or you will reveal yourself in some way, whether or not you want to. And I guess the example I would give is that when I first started writing, I was in my twenties. I’d never written any fiction before. The thing about fiction that appealed to me was this idea that you could escape from the confines of your own personality. And so I wrote a novel that was set in the world of mixed martial arts. It was all male characters. It was incredibly macho in a way. I’m not very masculine or macho, and I’m not a prizefighter. And so I believed I was writing very, very far away from myself. And it was again, only after the book came out that I realized that in fact, I was writing very much about my own childhood experiences of training and ballet.

That the relationship and the novel, which is between a trainer and a fighter, was very much my relationship with my mother. In that moment, I understood that you do expose yourself in fiction. You are everywhere in your fiction, whether you like it or not. It won’t be necessarily in the most kind of autobiographical way. It’s not always that there’s a character who is the writer, but the imprint of the writer is everywhere in the work. And you have to be willing to have that skin in the game. You have to be willing to allow that exposure. So that is a kind of more personal piece of, and maybe less practical or easy to act upon piece of advice that I would give to a fiction writer.

In terms of craft books, I have to say I have not read very many craft books to my embarrassment, although I’m now looking at my bookshelf and I can see a number of them on my shelf, but I haven’t actually read them. But I think reading is always the only way. It’s hard to recommend a single book in the sense that I think I tend very much with my students to try to tailor my reading recommendations to my understanding of the project that they want to write, because I think my role when I’m teaching is that I’m always trying to help the writer get to the version of the book or the story or whatever it might be that they’re trying to write, not the version that I think they should be writing. And so it’s really an act of imagining the book that they want to write and helping them get there.

But there are so many writers that I love. I love Natalia Ginzburg. I do recommend The Dry Heart again and again, it’s a kind of perfect slim little novella. It’s 87 pages. It’s extraordinary what she achieves in those pages. For anybody who likes Elena Ferrante, I think Ginzburg is a very, very important writer to be reading. I love Tanizaki. I love Chekhov like so many. I love Henry James, as I think was probably obvious for my answer earlier. James is a writer that I return to again and again, he’s one of the most important writers to me.

But I think, I would say that maybe this would be an actual piece of advice. If there’s a writer that you admire or book that has really spoken to you, one thing that I often do in that case is I read everything that the writer has written. And that’s instructive, not just because it lets you kind of trace the arc of their development as a writer, sometimes it can even be mildly reassuring. One of my favorite writers is a Spanish writer, Javier Marías, who died I think a year or two ago. And I started with a really extraordinary trilogy he wrote called Your Face Tomorrow, which is just an astonishing accomplishment. It’s one of the great kind of works so far of the 21st century, I think. And when you read that, you really feel like, “This is nothing … I will never scale this mountain.”

But then I went back and I systematically read through everything he wrote, and it was somehow so endearing and so tender to me that actually his early short stories are not works of perfect genius, that you can see him evolve, that he’s human himself. And there was something in the experience of reading all of his work, everything he has written or published, rather, from start to finish, that ended up being such an incredibly intimate encounter. I feel like I met him really in his work. And so that is something that I would recommend to anybody who wants to write.

LD: Well, now, I can’t let you go without asking about your next book, so can you tell us anything? I think it’s coming out in April, am I right?

KK: Yeah, that’s right. It’s coming out in April of 2025. And the novel is called Audition. And it is very much in conversation with both Intimacies and the novel I wrote before that, which is called A Separation. It’s about an actor. It’s about a woman in the middle of her life who’s preparing for a premiere in New York. And a young man approaches her and says that he believes he’s her son. And that is a start of a cascade of events that follows, that shakes her sense of what is reality and what is not reality.

But it is, again, very much a novel that has the same voice, that has an unnamed female protagonist, that is concerned with questions of interpretation, language, and performance. Yeah, and I will say it was so much fun to write. I often think it’s a silly thing to say because maybe it’s irrelevant to the reader whether or not the writer had fun writing it, but I had so much fun writing it.

LD: I feel like I can tell when I read a book whether the author likes the book that they write. You know what I mean? You just sort of get that. Well, that’s exciting. We’ll look forward to that one as well.

KK: Thank you so much.

LD: Yeah, thank you so much, Katie. This has been a fantastic conversation. I really appreciate you taking a part in this.

KK: Oh, no, it’s been a complete pleasure and thank you to everybody who submitted these fantastic questions. I really appreciate the generosity with which everybody responded.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet