PAWcast: Adrienne Raphel ’10 on Crosswords and the People Who Love Them

A deep dive into the history of the popular puzzles

Adrienne Raphel ’10 speaks with PAW about her new book, Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them. Raphel explains the history of the crossword puzzle, the different stylistic flourishes of The New York Times’ crossword editors, and the puzzle world’s biggest quandary: gender disparity among crossword constructors.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: Hi, and welcome to the PAWcast. I’m Carrie Compton. Today, I’m speaking with Adrienne Raphel ’10, who is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them. Adrienne is a poet and has also written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The New Republic. Currently, she’s back at Princeton, teaching in the writing program. Adrienne, thank you so much for joining me today.

Adrienne Raphel: Thank you for having me. This is a pleasure.

CC: Yeah. So, wow, a book about crossword puzzling.

AR: Yeah. (laughs)

CC: I was really excited when this came across my desk. As somebody who — it’s been an upward climb for me and crossword puzzles, I have to say. For a long time, I thought it somehow wasn’t for me. You can’t just naturally be good at them, per se. But, eventually, I decided, why am I so afraid of this thing? And I’d say for the like the last 10 years, I’ve been giving myself permission, and um, sometimes cheating a lot.

AR: Cheating is perfectly acceptable by my book. (laughter) And also that’s so wonderful. I think a lot of people have that fear, “Crosswords aren’t for me.” They’re for everybody, of course they’re for you.

CC: Yeah, exactly. And I really have to say, it’s opened up a space in my life when I couldn’t have imagined would be as rewarding as it is.

AR: That’s great. (laughs) That’s what I like to hear, yeah.

CC: Tell me how you came to write this book.

AR: Oh, gosh, it’s been a long journey. (laughter) But the funny thing is, I’m a lot like you, I am still pretty average at crosswords. But I realized, you know, one place I started this book, although I didn’t know I was starting it then was actually at Princeton. My sophomore year, I took John McPhee’s creative nonfiction seminar, and one of the pieces he assigned for that class was to write a short set piece that you envisioned in the middle of some longer piece. But write like a little short sort of aside, tangent, fun thing that you’d envision in the middle of a longer piece. So, I wrote this short tangent about crosswords, and specifically crosswords history in World War II, and more specifically, about a schoolteacher in England who was creating crosswords, and he created them like every day. But when you create crosswords every day, you also, like — it’s a lot of work, right? So, he would put the grid down in front of his students and say, like, “OK, help fill in the words.” And so they were helping fill in the words, but it turned out there was an army base sort of next door to the school, and the kids were picking up cool words that they had heard. And so, long story short, there were code words getting embedded into the crossword that this teacher didn’t even know about. British Intelligence officers knocked on his door one day and said, “Excuse me, we think you’re a traitor, and why do you have overlord and Juno and Mercury in your crossword?” And he’s like, “What?” (laughs)

CC: Oh, that’s so funny.

AR: So, I thought this story was amazing. You know, the assignment is “write the aside to the bigger story.” In my case, (laughs) as it turned out, that became the story.

CC: Yeah. That’s great. So, tell me about the history of puzzling. You sort of touched on it there, but let’s hear how this thing became such an institution in American culture.

AR: The first word cross puzzle was published in December 21st, 1913. This editor at The New York World named Arthur Wynne realized, “Hey, I need to fill blank space on my Fun page in the newspaper, and I’m in a jam. I’ve got a bunch of games in there, but what am I going to do?” And printing technology had gotten better about printing blank grids at that point, which was like fairly recent. And he liked word games and word puzzles. He’d seen word puzzles with grids that you had to fill in before. He knew word searches had been a thing for forever, acrostics and clues starting to be more of a thing, and he was like, “Oh, cool, I can print a blank grid, that’ll fill up a lot of space. Great. (laughter) And I can print clues with it and even more space, great, cool, and I can call it ‘Fun’s Word Cross Puzzle,’ and that’ll be the centerpiece of my Christmas edition.”

CC: OK.

AR: And he printed this, and people loved it, and he thought it was going to be a one-off thing. It quickly became very regular. His version of the puzzle, it looks like a diamond instead of a square, so it’s sort of like tilted. And then, also his version of the puzzle, there’s kind of, it’s not — I hate to say it it’s not a very good puzzle by our standards. What I mean by that is, the same word is clued — “dove” appears twice in it. It’s kind of all over the place. Some of the clues are super hard, like, “Fiber of the Gomuti palm.” What is that? (laughter) No one knows. Not a thing. He just needed the letters in there. And then some of them are like, “dove, bird,” okay.

So, it’s totally erratic. And Arthur Wynne, he liked his puzzle, and people got really into the crossword puzzle, he got really sick of it. He was like, “This is a lot of work. I can’t focus on editing this thing.” And he palms the puzzle off eventually to a young woman who had just started working at The New York World who was a secretary there named Margaret Farrar. Margaret Farrar, so, that’s an important name in crossword history. She was sort of really annoyed that he’d palmed this off on her, it was like, okay, well, a man palming off the hard job to a woman. (laughs) And also, “I don’t want to do this as my career. I want to be a journalist, that’s why I came here.” But then she eventually, through sort of pressure and then like all of us, she started doing the crossword and got into it and was like, “Hey, I can make this way better.” So, Margaret Farrar started instituting rules to make the puzzle more interesting and clearer and cleaner, and just a better solve for people, a better game. She was like, “Okay, every word has to be crossed with another word, it has to be perfectly symmetrical. The clues have to be something you don’t mind finding at the Sunday breakfast table.” Also, she started instituting standardization with cluing styles, too. So, Margaret Farrar turns this from sort of the Wild West of puzzling, into a more institutional game, which I think just makes it much more consistent. And Margaret Farrar, the name is super important because not only is she the wife of Farrar, of Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, the publishing company, but she’s the first crossword editor of The New York Times.

CC: Right. And, so we haven’t even gotten to the point in history here where The Times has the puzzle, because The Times finds it to be rather silly, right?

AR: The Times says, “Hey, we don’t need a game to lure our readers in.” Well, first they publish editorials saying, “This is a fad, nobody cares about it.” But finally, by 1941, they’re the only major metropolitan daily in the United States without a crossword puzzle. And on December 7th, 1941, the world changes. December 18th, 1941, a senior editor turns to the publisher and says, “Hey, there’s going to be blackouts, the world is crazy and the news is bleak, and we need something in our paper that’s not just a terrible headline.” Turns out the publisher really liked crossword puzzles and he’d been sort of surreptitiously doing them on the side in a rival paper. So he was like, “Oh, twist my arm.” (laughter) So, in February of 1942, The New York Times starts publishing a puzzle, but they make a big to-do about, “Okay, we’re going to be a really good puzzle. If we’re going to publish a crossword puzzle, we’re going to be the best crossword puzzle in America.” So, they hire Margaret Farrar to edit their puzzle, and they institute her rules and standards, and The New York Times says, “We caved, but we caved and we’re standing strong. We’re going to be the best puzzle.” And sort of very quickly, thereafter a lot of crossword-heads debate what is the best puzzle. There’s lots of — luckily, the landscape is such that it’s really rich, there’s lots of great puzzles out there. But I think throughout, certainly the second half of the 20th century into the 21st now, The New York Times is the gold standard of what is an American crossword puzzle.

CC: And there were very few puzzle editors, between Margaret Farrar and Will Shortz.

AR: It’s amazing to me, yeah. There’s been so few. There’s Margaret Farrar and Will Weng, for a little bit, and then Eugene Maleska and then, Will Shortz, essentially.

CC: Yeah. Talk about the difference between the old and the new school of thought about how a crossword was constructed, because I’m sure there’s people who have been doing the crossword long enough to sort of feel that atmospheric shift, but whether or not they’ve actually sat down and thought about it is another thing.

AR: That’s a great question. So, in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, The New York Times crossword puzzle, and I think most crossword puzzles in general, were what I’d call old school, in the sense that the clues were really pretty restricted to what you might learn in a certain Ivy League educated environment. And Eugene Maleska, who was a great crossword editor in many ways, he was very talented and skilled at making crosswords, but he had a very clear point of view about, “Okay, I want this crossword to be evergreen. I wanted you to pick it up 40, 50 years from now and be able to solve it. I don’t want anything in the puzzle that’s going to not stand the test of time.” So, in his view, that meant no brand names. That meant nothing extremely contemporary and pop culture, or in politics or economics, you know, that meant really limiting the scope of what goes in a puzzle to the kinds of things that were much more, I guess classic, for lack of a better word. That has lots of problems, the red flags just pop up all the time, “What cultures aren’t being represented in the crossword?” So, the crossword represented a very small sliver of culture at that point. One of the clearest examples of this is the word “Oreo.” Because, like, O-R-E-O.

CC: I loved this anecdote in the book, yeah.

AR: (laughs) Like, O-R-E-O is just a fabulous crossword word, because crosswords operate, they sort of live and die by four-letter words, too, because you just need them to fill out a grid. They’re great. Oreo’s fantastic — it’s like so vowel-rich. (laughter) You need them. So, problem is, Oreo’s a brand name. What do you do? Maleska’s solution, is to clue it as “mountain: prefix,” or like “mountain combining form.” I didn’t know this, apparently Oreo, like the prefix has to do with mountains. (laughter) Cool, great. Okay. (laughter) It kind of becomes an in-joke, and I think that’s one of the intimidation factors that the crossword has picked up as a stigma of, like, “Okay, this puzzle is not for me. It says ‘mountain: prefix,’ I don’t know what that is. It’s keeping me out.” Right? So when Will Shortz takes over as New York Times Puzzle Editor in 1993, he shakes things up, and he says, “Look, Oreo is a cookie. (laughter) It’s not a mountain: prefix, let’s call a spade a spade and move forward.” And so, this is great because this ushers in not only an era of brand names in the puzzle, but More importantly, it ushers in brand-new elements of culture that just hadn’t been seen there before. And nowadays, an answer like R-A-E is much more likely to be clued as like, Issa Rae.

CC: Exactly.

AR: The puzzle has become and is becoming just incredibly much more diverse, much more inclusive. It’s also responding to The Times more quickly, it’s responding to news cycles. And, I think that that is not a bad thing at all. I think it’s a great thing. I think the crossword is a space that’s an escape, but it’s also a better escape when it’s continuously adapting to what’s going on. The more pieces of culture the crossword can pick up and draw in and use for its benefit, just the better it’s going to be. When you have more stuff the crossword is drawing on more words and phrases and interesting pieces of language and your wordlist, that just makes for a richer database, which makes for a better puzzle. And more constructors being drawn to construct, and more people being drawn to solve.

CC: Well, that leads into my next question. Let’s talk about the constructors.

AR: Yeah.

CC: Who are they? And I want to hear about your foray into Will Shortz’s fortress in New York.

AR: Yeah, so Will Shortz edits The New York Times puzzle from his house in Pleasantville, N.Y., which is an amazing kind of puzzle palace. He has all these artifacts from puzzle life and puzzle world, like a crossword pinball machine in the basement was my favorite thing. There were so many great things. And he has a library of just all the dictionaries and encyclopedias you could ever imagine. When constructors submit puzzles to Will Shortz, they mail them to The New York Times, and then The New York Times kind of trucks them up to Pleasantville. So, his dining room is just totally given over to thousands of pieces of paper with crosswords on them.

CC: So, these are just submissions.

AR: Yeah, and the way it works is that, I mean, there are lots of people who — not lots of people. A merry band of people who submit pretty regularly to The New York Times, but they all submit through the exact same way. Everybody from me working on a puzzle at my desk, and knowing nothing about how to do it, to someone like Erik Agard, or you know, Lynne Lempel, these people who construct all the time, everybody is just sending them in by mail.

CC: Right.

AR: Yeah.

CC: And then what happens?

AR: Will Shortz and his assistants, so right now that’s Joel Fagliano and Sam Ezersky, they all look at the puzzle. So the bulk of their job is really looking at it and saying, “Does this theme excite me?” And then what does “excite” mean? That’s a very subjective question. (laughter) Excite might mean, “I’ve never seen this kind of theme before.” That would be really exciting, because themes get recycled all the time. Excite might mean, “There aren’t any super weird crossword-y words in here” — excite might be as tame as that, like, “Wow, they didn’t have to use something like E-N-E, like east northeast,” you know, or some sort of suffix that’s really annoying. Or, they might sort of say the opposite, like, “Wow, this has so many cool theme answers in it, like we’ve never seen,” I don’t know, “‘swipe left’ in a puzzle before, so I’m going to ask the constructor to see if they can mess with some of the weirder or less appealing fill to try to get that in.” So, they’re looking mostly at the grid, though, because the grid is the hardest thing to construct.

So, in a crossword, there’s two basic elements, right? There’s the grid, which is, you know, the grid, and then there’s the clues. So, constructing a crossword grid is technically like the most finicky part of it, because once you move one letter, you’re going to have to change the whole grid. They can fix the clues. And in fact, want something I found really fascinating when I was researching this book is that a crossword grid, you know, a filled-in grid with all the letters, can become radically easier or harder depending on the clues.

CC: Right, right.

AR: So, you could have a grid filled in with all these words, and you can clue them in really easy ways, like you know, what’s a clue for bacon? “fried pork at breakfast.” Cool, I know what that is, or like, “Brings home the blank.” I know what that is. But then something like “strips in a club?” That’s a super tricky clue, because your brain goes one way, and then you realize “strips” is not a verb, it’s a noun, and a “club” is not a dance club but a club sandwich, and then you’re good.

So, this is all to say that Will and his assistants are really looking for functional, great grids. They can end up re-cluing up to 90 percent of the words.

CC: Oh, wow.

AR: Yeah, and that’s something that takes a lot less time for them, and also they want to make sure that they can then calibrate and say, “Hey, the word ‘area’ has been clued, we know it’s going to be clued five times as ‘zone’ in the next month,” and the constructor who submits has no way of knowing that, right? So they will then jump in and say, “Okay, cool, we’re going to re-clue ‘area’, but it is fascinating that they really strongly lead towards, “Okay, is this grid working well?” And then some constructors are much more interested in creating great, lively clues than others. So, some constructor’s clues barely get touched, others get tinkered with.

CC: Yeah. So, talk about your try at constructing a puzzle.

AR: Yeah, so, this was fascinating to me, and I was on a residency a couple of summers ago, and I thought, “Wow, great, I’m writing this book. What’s a great use of this residency? I thought, “Oh, I’ll just try my hand at it.” Like, “I’ll get some graph paper.” I ended up getting crossword software, but... (laughter)

CC: You start with graph paper.

AR: Yeah. I was like, “It’ll take an afternoon.” I got the graph paper, it took three days. I was like, “I don’t know what I’m doing.” So, I quickly realized I was in way over my head, constructing a crossword is very, very tricky, at least as an entry point. Once you sort of get into it, you can do it more easily. The problem of putting a grid together, it just is really, everything is so tricky and finicky, and you get really adventurous at the beginning, and you’re like, “I can put all of these cool words into this grid,” and then you realize that there are so many rules that have to go on. It’s got to be symmetrical, which means — that’s the trickiest one. So, you put a word in a certain slot in a grid, and then a word of exactly that length has to appear in the slot that’s symmetrical to it. So, that quickly dictates the size of the grid, the types of words that can go where. So, there’s crossword-construction software, which is developed and really kind of changed the game over the past decade, in terms of more and more people can download this software, and it’ll do nice things for you, like it will create symmetry automatically in your grid, rather than trying to have to count out boxes on graph paper. And also, what a crossword software can do is you can download word lists into it, so it can tell you, like, you try to enter these letters and then you can sort of click a button, and it’ll say, “You’re never going to be able to fill in the rest of your grid because there’s going to be no letter combinations that will work in my entire database of words.”

CC: Oh, wow.

AR: I played around with this. There’s also sites online that will tell you every single way that every New York Times crossword — word in a New York Times crossword has been clued over time. The archives on this stuff are amazing.

CC: Yeah.

AR: So, I was having a lot of fun playing with that. You know, it can be kind of seductive and maddening to think of, like, “What’s the cleverest crossword theme I could come up with,” and then realizing, “Okay, I have all these clever ideas for theme answers,” I’m going to try to make a crossword that has all of these cool themes. But then, that’s like... (laughter) And then if I move one word, then my whole grid gets messed up. Yeah. So, it took me quite a while, I got really overambitious, tried to make some sort of crazy themes, had start from scratch lots of times. And then I sent my puzzle in to The New York Times, and I got a very kind note back from one of Will’s assistants saying, “Well, this is a really ambitious first attempt, and it’s not working.” (laughs) “At all.”

CC: So, there was always kind of a fraught-ness around women and crosswording for a long time, and you talk about this in the book, that to this day, constructors tend to overwhelmingly be male. Talk about the gender disparity in crosswording.

AR: So, the gender disparity is really interesting because in the very beginning of crosswording, the first New York Times editor, Margaret Farrar, a woman, but always constructors leaned more male than female, while solvers, that’s not the case at all. So, this came to a head, the amazing constructor Anna Shechtman, brought this up a few years ago in an article she wrote for The American Reader, it basically said “Where are the women?” Ben Tausig, who’s another crossword editor, also has written extensively about this. He’s thought about this a lot as well. A lot of other people have, this is just people who’ve been bringing it to light more recently, looking at statistics of constructors published in The New York Times and elsewhere, and there’s been — it’s sort of always been lower ratios, but then ratios that started in the ’90s as sort of like, three men to one woman were dropping off to like 10 percent women, something like that.

And there have been theories like “Oh, well, the same thing that’s happening in other STEM fields is happening in crosswords.” I find that a little bit difficult to buy. Ben Tausig, when he wrote an article about it, his point was that crossword editors at this point are overwhelmingly male. And so, even if they weren’t looking at constructor’s names, they just have a totally unconscious bias towards male constructors. Or, that’s one possibility.

I think what is very true and is great is that this is being brought to light, more people are kind of waking up to the fact that women can and should and do create great puzzles. In fact, just this month in March, The New York Times, around International Women’s Day, they had an International Women’s Week and published crosswords — all by female constructors. And The New York Times wasn’t the only one that did this. The Washington Post, I think The Wall Street Journal had several puzzles published by women, the LA Times. There’s a really great puzzle, an independent crossword puzzle out there called The Incubator that only publishes puzzles by women, and strongly encourages female constructors to get their start.

CC: In the book, you do a lot of ruminating about the place that puzzles take up in our life. What do you think they do for us as humans?

AR: That’s such a great question. I think that, you know, one way I’d like to think about this is that every time I start talking about crosswords to somebody, the conversation almost immediately jumps to something in their family, or something with their close friends, or something to the people who are close to them, like, “Oh, I don’t do crosswords, but my grandma does crosswords.” Or, “Oh, yeah, my friends and I started doing the Sunday puzzle together in college.” So, that’s been something that’s just been true throughout the process of researching the book is that I bring this up with people, and it immediately launches into a discussion about family friends. So, I realized, okay, the crossword, which seems like this very individual act, is tapping into something that’s so social and such an anchor, too. The other thing that comes up frequently when I talk about crosswords with people is, “Oh, I did crosswords in stressful times, or in times of great grief, the crossword is something that I built in as a ritual.” I think there is something that’s really soothing about the fact that you know exactly what kind of frustration you’re getting into with the crossword, you know. We’re living in really uncertain times, right? More uncertain than ever. Everything is kind of changing and in flux, and it can be really hard to know how to react. The crossword, you know what set of emotions you’re going to go through. If you’re me, you’re going to go into a crossword and you’re going to say, “(sigh) I don’t know any of these.” And then you’re going to say, “I know one of these. I know two of these. Oh, I got that one wrong. (laughter) I know one of these. Okay, here we go.” (laughs)

So, I think it’s really great because it’s not really turning your brain off, it’s just kind of allowing your brain and sort of then your body and your emotions to reset

CC: Well, thank you so much for joining me today, Adrienne.

AR: Thank you so much for having me.

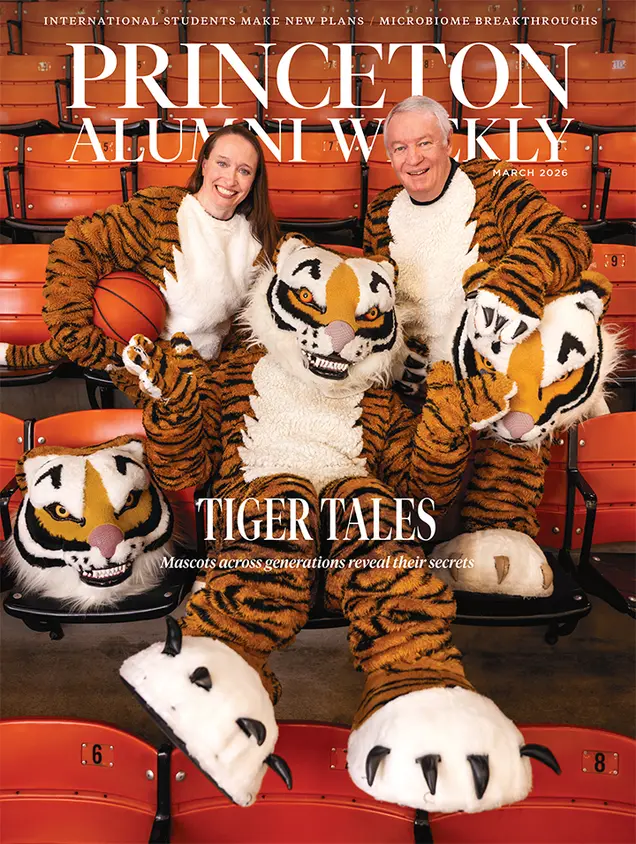

Paw in print

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

1 Response

W. Jeffrey Marshall ’71

5 Years AgoFascinating Topic

In response to “Adrienne Raphel ’10 on Crosswords and the People Who Love Them” (PAWcast, posted online April 2): I’m familiar with some of the history of crosswords — in fact, the “World” was the answer to a recent clue I came across about where they started in the U.S. — but this was an intriguing look not only at their history but their evolution. I’ve been doing crosswords pretty religiously for over 50 years, and while I’ve sensed some of the changes in the New York Times puzzles, Adrienne offered some real insights about those.

My brothers and I picked up our love for crosswords and other word games from my father, Ted ’42 *48, who used to do the daily puzzle in 10 minutes on his commute to NYC. He was an amazing solver, and actually sold a few puzzles to the New York Herald Tribune in the ’50s. Construction is an incredibly difficult exercise — as Adrienne says, one letter can destroy a whole section of grid. I’ve completed a couple — more for my own amusement than anything — but the results were less than spectacular. I did submit one to Will Shortz years ago, and got a polite but firm rejection.

I salute Adrienne for her research and her modesty about her own skill. Champion competitive solvers, as I’ve read about them, may be seen as word nerds but can be as sure about their own abilities as Bobby Fischer was about chess.