PAWcast: Author Bryan Walsh ’01 on Existential Threats Facing Humanity

Very unlikely is ‘not the same thing as zero, but we as human beings tend to conflate those two’

Asteroids and volcanoes and biotechnology — oh my! Bryan Walsh ’01 discusses his book, End Times, about the existential threats facing humanity. Walsh and host Carrie Compton discuss eight possible events that could lead to human extinction, from pandemics to nuclear war to aliens.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

Walsh, a former foreign correspondent, reporter, and editor at Time, is editor of Medium’s science publication, OneZero.

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: Hi and welcome to this edition of Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast. I’m Carrie Compton and with me is Bryan Walsh, Class of 2001. Bryan worked for Time magazine as a foreign correspondent, a reporter, and an editor. And today, he is the editor of Medium’s science publication called OneZero. Today we’re here to discuss his new book called End Times: A Brief Guide to the End of the World; Asteroids, Super Volcanoes, Rogue Robots, and More. Bryan, thanks so much for making time to come to campus and record this podcast with us.

Bryan Walsh: It’s great to be here.

CC: So, I want to start by saying that your book might sound a little bit like a downer. But, having read it, I really thought it had a strong commentary about the resilience of the human condition. I think that a lot of that got set up for me in the tone of your introduction, where you establish two facts: One, as humans, we have a sort of innate inability to conceive of our own demise, let alone the demise of our entire species. We also have a tough time thinking about our place on the planet along geological lines, which is to say, in the entire existence of the planet, we are but a nanosecond. Kind of set that up for our readers too, about what does “existential” mean for us humans.

BW: Yeah it is very difficult, I think, for us to conceive of the end. And in part, it’s the fact that we tend to focus on risks or threats that feel most available to us. So, we focus on what the media might be telling us, we focus on what’s happening in our own lives. And that can kind of go either way. We can sometimes focus on threats that aren’t really that big a deal, because they get reported on a lot. But we can also miss things that are actually quite important, just because we have no experience with them. And, obviously, since we’re all here, we’ve never really experienced a true existential threat — and that means, really, a catastrophe bad enough to cause human extinction or something very close to it.

So the very fact that we’ve never experienced it makes it hard to make it feel real. And even though most of the risks that I deal with here, as the subtitle suggests, things like asteroids, super volcanoes — those are just the natural ones — they’re very, very, very unlikely. They happen only occasionally over the course of the very long history of the planet. Very unlikely, very, very unlikely, not the same thing as zero, but we as human beings tend to conflate those two.

We don’t really do well with the unexpected or the things that could come out of nowhere. And then when we look at that long period of history, we as people, obviously, if we live 100 years that’s quite a while; as a civilization we’re looking at like, 10,000 years maybe; as a species, a couple hundred thousand years. And that’s, a tiny, tiny, tiny amount of time based on the 4.5, 4.6 billion year history of the planet. And a lot of things can happen in the course of that time. And so, it’s where the collision between our short human experience versus the very long experience of the planet — when those two things clash, that’s why we look at this and we can’t really imagine this possible. And we need to, because you have to take them seriously and see them as real before we can actually begin to do something about them.

CC: So in your book, you outline eight possible events that could possibly lead to human extinction. Let’s do one by one, and then I’d like to hear why you decided to include each one, and also, the various prescriptive measures that you kind of cover in the book about possibly averting some of these. So, we’ll start with asteroids.

BW: Asteroids are the real cinematic one. And I think it’s not just because we’ve had movies like Armageddon or Deep Impact, that really, seared themselves into our consciousness, but when we think of something coming to get us that’s natural, I think an asteroid from the sky really fits the bill. That’s what did in the dinosaurs for the most part, 66 million years ago. It seems real to us. Actually though, the funny thing about them, is that they’re the risk that I’m least worried about. And that’s in part because they’re really infrequent, at least on the scale that we’re looking at, where you’re talking about a collision with an asteroid many miles wide, you know, three or four or five or six miles wide, and that’s like, millions upon millions of years pass before that could happen. But also, because we’re actually doing something about them. And that was really quite exciting for me to see.

Starting in the ‘90s, NASA really embarked on a program called Spaceguard, that had astronomers looking and tracking and finding all of the larger asteroids out there that might potentially hit the Earth. And I spent some time at the Catalina Sky Survey outside Tucson, Ariz., overnight with people who do that work. They’re looking through these telescopes, searching for near-Earth objects, tracking them, tagging them. And because you can calculate their orbits, you know where they’ll be in the future. So that makes them predictable in a way that really no other threat is. If one’s coming at us, we have something we can do about them. There are ways we think to deflect them. And deflect makes it sound like, you know, it’s like Missile Command, the old arcade game, and you’re going to shoot them out of the sky. It doesn’t quite work that way. What you really want to do is — asteroids and the Earth are both in an orbital path, they’re both circling the sun, and if they’re going to collide, it’s almost like two cars merging in a highway that meet each other. One has to give way. So, you’re not going to slow down the Earth, the Earth is too big, but you can slow down an asteroid, and you can do that a number of ways.

You can shoot a laser on it that would kind of change its momentum. You can actually ram into it with a space craft or a satellite of some sort. And you can use nuclear bombs. And again, if you’ve seen Armageddon, you kind of know how that worked. And while everything about that movie was wrong, up to and including, it would have made a lot more sense to train the astronauts to drill the asteroid than train the oil drillers to travel to space, as Ben Affleck himself pointed out I think in the director notes, you know, you would actually put the bomb in the asteroid and then blow it up that way. And you don’t break it into pieces, but rather, that gives it more force, and that slows it down more. And so that’s pretty exciting, when you think about the fact that asteroids have been hitting the Earth forever, you know, that’s a real risk that could happen, we can actually stop that, and that’s exciting. That to me, starts out the book in a way that says, like, OK, even something literally — a hammer from space, we human beings are now in the position to do something about it if we take it seriously, if we do the kind of funding and programs we need to do.

CC: OK, volcanoes.

BW: Yeah. Volcanoes. Volcanoes are great. Volcanoes are the one no one really realizes is coming. And they’re actually considered by existential-risk experts to be the biggest natural risk we face, more so than asteroids. And that’s because they happen more frequently.

I talk about super volcanoes, and that’s a specific class. Volcanoes are ranked on what’s called the Volcanic Explosivity Index, which is just a Richter scale for volcanoes, one to eight, eight being the highest — that’s a super volcano. They really only occur every few 10,000 years, or you know, 20,000, 30,000 years. Which seems like a lot, you know, you could fit basically three times the human civilization in that time period, but on a planetary scale that’s actually pretty frequent. I talk about one called Toba, about 74,000 years ago that really, you know, some people think may have brought the human race at the time close to extinction. A super volcano would be the equivalent of like, a few hundred Mount St. Helens, if you remember that from 1980, all blowing up at the same time for weeks on end. You have sulfur and debris and soot put into the atmosphere, and that would actually dim the sky.

So, you’d have really rapid cooling — what’s called a volcanic winter — and that’s where the really killing effects would happen. You’d actually see temperatures drop, you know, 15 degrees, 16, 17 degrees Fahrenheit possibly. You would not be able to farm as well. You would potentially be looking at something like global starvation and that’s scary. And the chance of that happening, again, within our lifetime, or our children’s lifetime, is very, very, very, very low. But, you know, there’s about 20 of those out there. One of them is Yellowstone.

So, really what we could do there, is try to prepare. We can monitor these, we can see them coming, which is important. So, if you knew Yellowstone was likely to erupt over the course of the next, you know, six months, you could take steps to prepare the food you’d need, you could obviously evacuate people. But that’s one where the Earth is a dangerous place, and we forget that because we’ve been lucky enough to live over the last 10,000 years in a very stable climate for the most part, very conducive to human civilization, no guarantee that continues forever. Past performance is no guarantee of future success. So, while it’s not something I really worry about that much, it’s definitely something that’s real and something you have to watch out for.

CC: OK. Nuclear weapons.

BW: Nuclear weapons are the one, if the world were to end right now, us, you and I talking right now, that would probably be it. And it’s something we’ve kind of put out of our mind. I’m 41 years old, which meant I lived and grew up in the last stage of the Cold War, and that was real, you know. I mean people worried about that. We have fallout shelters still. Then the Cold War ended, and it seemed like that risk went away. It never did really, though.

Even during the years when relations between the U.S. and Russia were at their best, I’d say, those missiles were still pointed at each other. They were still ready to go at a moment’s notice. And of course, what we’ve seen over the last few years, is those relations get worse and worse. And instead of these two countries and the other countries obviously getting nuclear weapons agreeing to reduce warheads further, we’re seeing both nations really amp up their nuclear programs.

The U.S. is doing that, spending hundreds of billions of dollars to modernize and introduce new weapons. The Russians are doing something similar. The U.S. just pulled out — recently this summer — out of the Intermediate Missile Test Ban Treaty, which raises the risk a lot. And then you see, of course, new players like North Korea with these weapons. Or you see India and Pakistan, two countries that have fought multiple wars, that both have nuclear weapons.

And again, if that were to happen, you’d had devastation where these occurred to a degree we can’t even imagine, but you’d also have that same nuclear winter, similar to the volcanic winter effect. And what’s scary is that, it’s not that someone would try to win a nuclear war or start one on purpose necessarily, but it’s very easy for things to spiral out of control. We saw multiple times in the Cold War where people — there was a mistake, there was a computer error that almost resulted in an exchange. That could happen again. You could have a situation where one country makes an aggressive move, and the other responds in a way that the first country didn’t expect. And there’s no defense against them. And it’s just something that really worries me.

It’s not on the public’s radar in the same way, I feel like we’ve kind of put it out of our mind, but we shouldn’t. And it also really — represents the first time that humans could do this. Before that, we were worried about asteroids coming from the sky, or super volcanoes beneath our feet. On July 16, 1945, when the Trinity test occurred, the first nuclear bomb explosion, that was when humans sort of entered the game. Suddenly, we can destroy ourselves. And things were never the same after that. And it’s only led to other ones we’ll be talking about later on in the podcast, like new kind of risks, all coming from what human beings can do.

CC: So, climate change. This is one that you’ve got a lot of experience with from your reporting. And this is also kind of like the specter of nuclear weapons as well, because is somewhat man-made, but this one is kind of also in conjunction with our natural planet as well. So, talk about this. Not that we need to talk about it anymore, but yeah.

BW: Really fun. It’s a really fun subject to talk about, and yeah, I did spend years reporting on this. And climate change — you’re right. I think a generation can really only focus on one of these at a time. And younger people —people younger than me, or, you know, older than me — this is the one they focus on. And it is a very real — and it’s also different than the other risks in that, you know, a nuclear war happens, or it doesn’t, you know. An asteroid hits us or it doesn’t hit us. Climate change is always happening, it’s been happening for some time, it will continue to happen, it will be a continuum of destruction, essentially.

We can begin to predict some of it, we can control some of it, but it’s not sort of binary in the way these eithers are. And that kind of makes it hard to deal with. At the same time, what I found was that it’s not — there’s been more recently, I think, this sense that we’re on a real clock, that if we can’t zero out carbon emissions, drastically reduce them over the next 12 years or so, that’s it. It’s over. And that’s not true. For climate change to be a truly existential risk, it would have to be on the very high end of how bad it could get.

And two things would need to happen there: We’d really have to do almost nothing, really, almost purposefully not reduce carbon emissions, not even accidentally. And then the climate would also have to respond in the most extreme way to what we’re doing. I don’t think that’s very likely, I think that’s sort of at the far end of the likelihood scale. But at the same, it may happen, and it’s going to make other things a lot worse. So, what worries me in some ways, it’s not just that climate change itself is going to cause a lot of death and devastation, which it will, but it will be a destabilizing factor across the board, which then makes other risks more likely.

It makes it more likely you’ll have a terrible pandemic, it makes it more likely you could have a nuclear war, for instance. And what’s challenging here is that it’s completely within our power to do something about it, but I really looked at it as a way to sort of examine why it is we don’t act on these. Because climate change is the most famous example of a risk we don’t act on, or at least not really, or not enough. And that’s in part because climate change is always pitched towards the future. The carbon we emit right now will be in the atmosphere for decades, even centuries in the future, which means that we are now affecting the climate for people who are not even born yet. And it’s tough because we don’t really take the future seriously. We don’t even take our own personal future seriously. I have an example in the book where you can put yourself in an fMRI tube and ask yourself to think about you right now. A certain part of your brain, that’s sort of associated with identity will light up very strongly. If you think about yourself 20 years from now, it will light up less so. And that’s because you — own person in the future is kind of a stranger to you. And then when you think about people you don’t even have a connection to in the future, then it just doesn’t exist. It’s like they don’t matter to you.

And the reality is that’s the way economics works. We don’t really value the future, and the farther out we go, the less we value it. And climate change requires us, really, to make present day actions or sacrifices to benefit the future, which is just not something we tend to do. Again, we don’t even do it for ourselves really, otherwise we’d all save a lot more on our 401k. And so, in the course of reporting, both this book and back when I was at Time magazine — going to conferences like Copenhagen, UN conferences, and just — we get close and then it would just stop. And — a lot of reasons for that, a lot of political denialism, a lot of oil industry people pushing against this. But, at the end of the day, human beings just are not really good at thinking about that. Which is why, most likely we’ll end up going some sort of shortcut route. Could be geoengineering, could be something like that, anything that allows us to just act now, as opposed to plan for the long term, which we’re just not going to do.

CC: Right, so diseases. One of the things I found interesting was that you said that, actually, smallpox could be our worst nightmare as it was for generations before us. Or a super-flu. So, tell me about where you see diseases fitting into this.

BW: So, disease, it seems very ordinary, but infectious diseases killed more human beings than anything else — any war, any natural disaster, it’s the way we’ve generally gone. And it continues.

One on hand, we’ve created vaccines, we’ve created antibiotics — that has really reduced the cost of a lot of these diseases, and we’re continuing to do that, which is really great. At the same time, a more globalized world where we’re spreading out into new environments really increases the likelihood of new diseases emerging. Since 2000, we’ve seen a number of completely unprecedented diseases come up.

SARS is one, which I was in Hong Kong to report on, new kinds of avian flu. We had a flu pandemic in 2009. We had Zika, obviously. And we’ve had Ebola really break out in a way we’ve never seen before. And that’s kind of odd, because those two things coincide. On one hand, really countering disease. On the other hand, constantly being challenged. And that's going to continue because now, there’s no place on Earth that is really remote. A new disease can arise in some unexpected place in Central Africa or in parts of Asia, and all it takes is one person getting on a plane and it can go anywhere. And that’ll continue, I think.

The good news is that diseases that really come out of nature are sort of limited in how much they can spread and how virulent they can be, like, you know, you have something like Ebola — very virulent, kills a very high percentage, but hard to spread. And then you often see vice versa, measles — very contagious, generally doesn’t kill people. And the simple nature of a disease out in the wild is it tends to sort of attenuate, because that’s the nature of evolution. It doesn’t want to kill everyone, that’s not in its interest. So that’s a good sign we’re not likely to all be wiped out by something coming out of nature. But it changes if it’s something we’re making.

CC: Well, which brings us to biotechnology, which is another chapter.

BW: Exactly. Biotechnology is my favorite chapter, and also the most dangerous risk. It’s the one that really worries me the most going forward. Beyond, obviously, something terrible happening with nuclear war, this is one that’s going to be the most challenging to deal with. And that’s because we have these new tools — things like gene editing, CRISPR being one of them, synthetic biology — that gives us, really, the essential the power to rewrite the very code of life. And what I had said before about certain kind of laws of evolution that limit diseases coming out of nature, well we could override that with these new tools. We could make viruses — you said super-flu — that are both very contagious and very deadly. And what’s scary is that not only can we already begin to do that, but more and more people are able to do that in the future, because this is getting cheaper and cheaper.

It’s a little bit like computer programming. We’re — I think — not far from the computer science program here. If you went back here in the ’60s or so, you’d see huge mainframes that required you to punch cards to program it — really limited what you could do. Fast forward to now, everyone can have a computer. They can easily create programs, and as a result, it’s very easy to do bad things on computers, you know, to create malware, to create viruses. That’s the direction we’re moving with biology.

It’s getting cheaper and cheaper, it’s getting easier and easier, and faster and faster. And if you can program biology like you can a computer, you’ll be able to do amazing things. We’ll create new cures for diseases, we might create new crops that are better for climate change, any number of things. But we’ll also be in power to do really terrible things too. And there are people out there who will do really terrible things.

They might do it on purpose — terrorists might want to do this. Certainly, it’s an incredibly effective weapon, or people could do it accidentally. Scientists could be doing work — they already do this work — where they enhance viruses to study them better. To sort of see how they might evolve in nature, but in doing that, they raise the risk those could get out, you know, and that happens.

Just last month actually, the U.S. military’s top infectious disease lab was shut down for safety concerns. That’s a lab that works with things like Ebola. Not to keep you awake, but that does happen, and that’s scary. And the more and more people who can do this, the harder and harder it will be to control, and really the better the chance that something goes wrong. Because once you begin to be able to break down the nature of life, and then once you can just program it, you can make — anything would be going too far or pretty close. And it’s one thing if only large companies or countries can do that, maybe you can control that, but if it’s something you can do increasingly in your garage or your backyard, the way you can with computers, then it’s very hard to control, and that’s when you get a really high risk.

CC: So, the computers bring us to AI. This seemed really scary to you as well. One of those chapters, it seemed that you took very seriously. And I sort of went into it not thinking it was as big a threat as you.

BW: Yeah, AI is a tricky one because it sort of — the other ones I all know are real, for sure. They may be very unlikely, like asteroids, they may be not as bad as we thought, like disease or even climate change. But AI — it might be impossible. Like, it might be impossible to create the kind of like, artificial general intelligence we all worry about, the Skynet, the things like that, that could somehow take over. And if that’s the case, well then we really don’t have that much to worry about. But if it is possible, and someone will do it, then it’s really very risky. Because if you create something that is more intelligent than you, you know — humans are only at the top of the food chain here because we’re the smartest species out there, not because we’re the strongest or the fastest, just because we’re the smartest. And if we’re displaced in that — look what’s happened to so many other species on this planet. We have essentially driven them to extinction. Not really, generally, because we try to, you know, we’re not trying to hunt them down or because we don’t like gorillas or something, but because we have goals, we want their space, we want their habitat, and it’s too bad for them.

And you could see a situation with a very powerful AI that could be something similar. Because a superintelligent, which is kind of how they classify them, wouldn’t just be like, oh, smarter. It’s not just like smarter than me, the way that Albert Einstein was smarter than me. It’s like, smarter than Albert Einstein is than like, a puppy. That’s how vast the difference is going to be, so there’s really no way to control that.

Scientists work on AI ethics, AI control, with the idea that you might be able to do that, but the reality is, if it’s possible, I don’t see how you do it. It really is almost out of the question. So you almost have to hope that it’s not possible, or you hope that people won’t do it, but you know, the benefit you might get from this, especially if you’re the creator, is so great that it’s a bit like another nuclear arms race, where countries currently — China’s definitely doing this, the U.S., companies like Google, Facebook, are competing to develop the best AI and I don’t see anything that’s likely to make them stop.

So, in all honesty, this is one situation where I kind of hope science isn’t as good as it thinks it is, because if it is, we could be in trouble. You can create a really impressive AI that’s narrowly good at certain things, like playing chess for instance, or certain kinds of math. What they can’t do — that chess-playing program, can’t tell you why it’s playing chess. If you set the room on fire, the program was in it, it couldn’t do anything about that. It’s not able to generalize its skills the way any human be — even my 2-year-old son can do. So, it may that that’s impossible. Maybe there’s something in biology that you need to create that kind of intelligence. Maybe it’s not replicable in silicon for some reason. And certainly, if it were, we’d see something like self-driving cars coming around faster, and that’s not the case. It may simply be that this is beyond our abilities, but at the same time, what I’ve learned from studying the history of science, is that it’s always a mistake to assume something is impossible.

CC: You do this great analogy with the Sorcerer’s Apprentice — talk about that.

BW: Yeah, and I’m indebted to a guy named Luke Muehlhauser at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, who had this idea. Mickey basically like, you know, he’s the apprentice, he wants to just get some work done so he can take a nap, and so he sort of, without really knowing how it works, casts a spell to make the broom fill the cauldron for him. And it gets out of control very quickly, he doesn’t know how to turn it off, and he’s trying to stop it and he’s trying to tell the broom not to, but the broom only has one command: Fill the cauldron. And it won’t be dissuaded from that.

And when he tries to destroy it, the broom just keeps going, because being killed would be in the way of achieving its goal. And that’s not a bad way to think about how an AI might work. We give AI instructions, basically — you have to think of it as like an efficiency machine. And it will find the most efficient means of reaching its goal, no matter what. And in doing so, it may do things that we think are wrong, inhuman, terrible, but it doesn’t have those ethical guardrails, and it’s very hard to program them in. It’s hard to program a computer with ethics, because it’s hard for us to understand them.

Think how long we’ve been working on ethical problems as a species. So, are you going to count on computer guys to program that in? We haven’t figured it out, so it’s tough to put it into a machine, and so what you have is like, Mickey has activated powers beyond his control, and he would be in a lot of trouble if the sorcerer hadn’t shown up at the end of it, but of course, there is no sorcerer here, it’s only us. We’re only the apprentices, and that’s all we have, and we’re kind of playing with powers that might be a little bit beyond our control.

CC: Sort of like a genie in a Twilight Zone episode. He’s going to grant the wish in exactly the one way you hadn’t considered it.

BW: Yeah it’s perverse in how it ends up playing out.

CC: So, my favorite chapter, was the final chapter. Aliens was the eighth existential risk.

BW: Yeah, I quite enjoyed this one. So first off, you know, we think of aliens — this is another place where I think Hollywood plays a role. A lot of movies, Independence Day comes to mind, where all of a sudden, aliens come to the earth, and it seemed like they’re going to wipe us out, but then we sort of all come together and beat them.

Here’s the reality: If there’s a species out there that has the capability to travel across the stars and come to Earth, and they have hostile intentions, we’re done. There is no fighting back, they would be so much more powerful than us. It’s a little bit like if a band of stone-age cavemen tried to fight the U.S. Army, but it’d be even bigger than that. So that’s one thing, and you know, we don’t know what they’ll be like either. They might be so different than us, it’s hard to even know. They could even just destroy us accidentally. We’ve seen civilizations encounter each other here on Earth, and often it doesn’t go well.

The story of the Americas is really essentially that story. I don’t know why it would be different with aliens. And then there’s a possibility that they don’t exist, and that’s a risk in its own way, and that’s because right here in Princeton actually, over at the Institute for Advanced Study, Enrico Fermi, who’s a physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project among other things, he was having lunch with some friends of his, and basically he just sort of burst out like, “Where is everybody?” And was talking about us like, “Where are the aliens?” Huge galaxy, and what we increasingly learn is lots of planets that could potentially support life. That’s new actually, we discovered with some new satellites and some new telescopes, and yet no evidence. No signals after decades of searching, no evidence of biology, nothing as far as we can see.

Now it’s possible that we just haven’t looked far enough, it’s a big galaxy, it’s easy to miss. It’s possible they’re hiding for some reason, which is kind of weird, who knows, that could be something, or it’s possible that they don’t exist and it’s possible that they did exist and have destroyed themselves. And that’s kind of what concerns us there. It could be that civilizations, when they reach a certain level of technological development, destroy themselves. And if that’s the case, say if we find evidence like archaeologists do of civilizations beyond our planet that did exist and are now gone, that would be worrying, because it may make us think that could lie in our future. And that’s sort of the two-fold nature of that threat. It’s both the possibility that they do exist, and they could want to wipe us out, and then probably even more so, the possibility that their presence or absence indicates some bad sign about our own future as a species.

CC: So, the final chapter, well, the penultimate chapter, deals with survival. And that would be a good one to put in your go-bag for your prepping. Talk about some of the different ways that you could actually muster through a volcanic winter …

BW: Yeah, I mean it’s funny because there’s a huge industry in the United States around doomsday prepping. Millions of people are involved in this, there are big expos, people ranging from stuff they keep at home to vaults that they’re now renting out in places like South Dakota or Kansas, there are very rich people who are actually getting their estates in New Zealand, which they think is safe — although, important thing to remember about New Zealand, is that it’s actually the site of the last super volcano eruption, so, it’s not the most safe place in the world. It’s — that said, very nice, a lot of sheep.

But the reality is that you can’t really prepper yourself past the kind of catastrophes I’m talking about here. These are global ones that will last for years. There is no way to go out into the mountains with your own supplies and stay safe. It really requires us to come together as a species. One way to look at it is like, how will we feed ourselves? Because in the case of volcanoes, asteroids, nuclear war, they all sort of share that winter aspect where temperatures drop significantly, farming becomes very difficult, we have the problem of how to feed survivors. And so I talked to a few people who have done some very interesting research around like — well, we could grow a lot of mushrooms off of the trees that would actually die in this winter, and that could actually be scaled up; we could eat insects, which I’ve done before, it’s not awful, a lot of people do it now. Rats grow very fast, and they don’t like the sun, so they could be useful. You could even actually grow a form of algae, sort of, and bacteria processed by natural gas. There are all these sorts of things, and the key here is that you need to think about it now. It’s not a matter of storing enough food, because if you were trying to feed all these survivors, just with stuff you stored, it would take a stack of food up to the moon and back 40 times over.

What you need to do is figure out ways to actually deal with the aftermath. And that’s where planning comes in. So, you can do that, and there are some people working on that right now, and it would be great if we had more support for that. Really sort of extreme efforts is you could actually create sort of these vaults or refuges, not for after-the-fact but actually before so. Like imagine you sort of selected out of a draft, like 5,000 people, that represented a variety of backgrounds and skills, and said, “OK, for a year you guys are going to go down there, and just in case anything happens to the rest of us, you’ll be here to like, come back up and restart civilization.”

That sounds insane, I understand that, I’m not sure anyone would really volunteer for that, but you know, that would be a very effective way. Because then you guarantee that the future goes on. And that’s super important because it’s not just about us, the end of the world, it’s really about the future you won’t have otherwise. Because look, there’s 7.7 billion of us, something terrible happens, we all go extinct, that’s very bad for us, clearly, but you lose far more people. Like, if you didn’t have that event, you would have billions, tens of billions, hundreds of billions, maybe more, people who would live. And you lose them if you go extinct. That’s where the responsibility for us right now really comes in. It’s not just about keeping ourselves safe, it’s about ensuring that there is a future for all of humanity, and that’s one way to do so.

It’s almost like, you know, a bank, only for human beings and human skills, so you could do that too. Or lastly, if you’re like Jeff Bezos, another graduate here, you can send us all into space, and that means we’ll be safe up there. Which I don’t quite agree with, because space is really hard, like you’d really have to screw Earth up a lot before space is a better place to live. So, I don’t really look at it the way that he does, or Elon Musk I think, as like a refuge from existential risk. But I do agree that the idea is we will — we should keep expanding, I think that’s important, that is where our destiny lies. We continually grow, we continually innovate. So, you know, by all means send me up, but not the expectation that I’m going to live the rest of my life there, because I like Earth a lot, actually.

CC: Yeah. So, what do you hope people learn from the book?

BW: Well I hope they learn what to be worried about. I think a lot of people walk around today, and surveys and polls bear this out, just kind of panicking. And I get that, because there are a lot of bad things happening right now. But a lot of it, it’s because we live in a world of a hyper fast media, which I’m a part of, new tools that just are constantly shouting at you, every day, each and every day. And you don’t know what to tell what’s real, what’s not, what you should be really concerned about, what you shouldn’t be.

And so, I really hope people look at this and kind of get a better sense of like, OK, what’s the real risk situation out there? What should you really be concerned about? What should you really be working on? Because to me, these are some of the most important problems facing us. They go beyond, just the sort of day-by-day news we see, to like, megacycles that’ll effect centuries. And so, I really hope people get that, and I hope that actually makes them feel a little bit better, because it helps them put that in context.

So, for one thing, they know that we’ve always lived under certain kinds of threats, that’s not something that just started in 2016 for instance. But there’s also things that we can do about that. And I met a lot of people over the course of reporting this book who are deeply — working really hard to avert these risks. Whether they’re at NASA and dealing with asteroids, whether their volcanologists, whether they’re epidemiologists in the front lines of these diseases, whether they’re biologists who are actually trying to craft rules around using these new technologies to make them safer. So that makes me feel much better.

My wife and I had a child for the first time while I was working on this book, which I do not recommend for other authors, because it’s demanding. But at the same time it did give me a real sense of membership in the future that goes beyond — and I don’t think you have to have kids to feel that, but just for me, it sort of — I can see him and it kind of makes it real in that sense, and the book begins and ends with him to a certain extent, and I really do have hope for the future. I don’t think we’re going extinct, ultimately. I think we can avoid those end times, I really do. And it’s up to us if we’re going to do it.

CC: Thanks so much for joining me today.

BW: It’s great to be here, thank you.

Paw in print

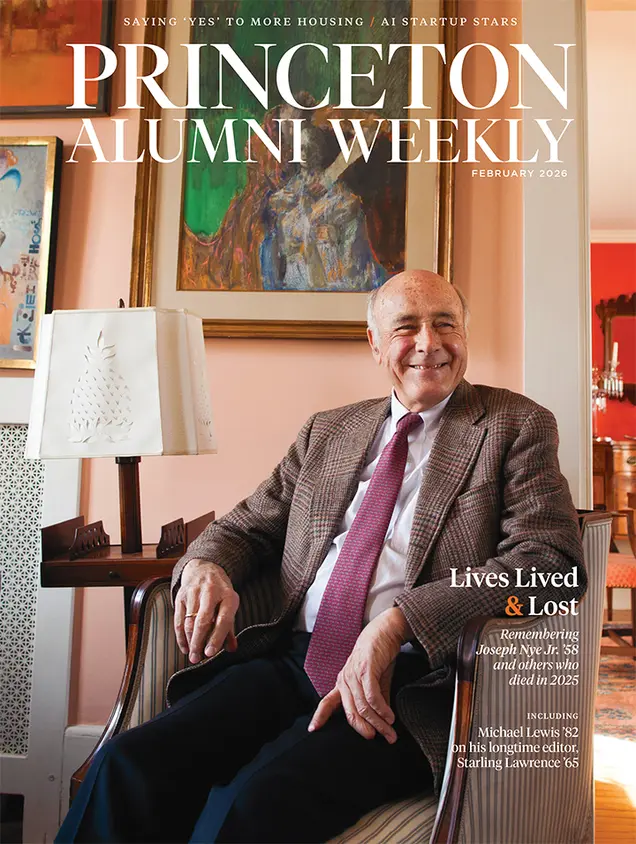

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet