PAWcast: Author Lisa Gornick ’77 on the Writing Life

Family histories intertwine in her new novel, The Peacock Feast

On this month’s PAWcast, novelist Lisa Gornick ’77 discusses her new book, writing, and her former career as a psychotherapist in an interview with associate editor Carrie Compton. “As a therapist and then as a psychoanalyst, I was really trained to hear unconscious themes, to see the way that stories unfold, and to hear the way that emotion is concealed in language,” Gornick says. “And so, I felt very much as though I was using what I knew as a student of literature in the therapy room — and the reverse as well.” Her latest novel, The Peacock Feast (Sarah Crichton Books), was published in February.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: You’re listening to Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast. I’m Carrie Compton, and today I’m speaking with novelist Lisa Gornick ’77, who has recently published her fourth book, The Peacock Feast. Lisa was a psychology major at Princeton and went on to practice psychotherapy, all the while pursuing her love for writing on the side. Lisa discusses her new book and how her dual passions — psychology and writing — worked in tandem for many years, and why she ultimately chose to pursue writing full time.

CC: I’d like to invite you to talk to us a little bit about your journey to writing.

Lisa Gornick: I was at Princeton in the creative writing department back before it was at the Lewis Center, when Ted Weiss ran it. And I was in, freshman year I was in poetry workshops and throughout my tenure at Princeton. And I actually got interested in psychology because of a volunteer job I did my first year at Princeton which was at a nearby, I think it was called Yardville State Prison. And while I was there, I was invited by a professional, who had been an inmate himself at one time, to sit in on these kind-of therapy groups he was running with the inmates. And I was so mesmerized by their stories, and so taken with the way that the storytelling was itself therapeutic that that set off my interest in psychology. So, I pursued the two of them in parallel for a very long time. And I actually was at one point in psychoanalytic training and doing what was essentially an MFA at NYU at the same time.

CC: Oh, wow.

LG: And they worked very well together for a long time. I’ve sometimes described this as it was a very happy marriage between the two professions because they draw on a lot of the same skills. And then like many good marriages, a divorce was required. I just reached a point where they no longer felt compatible for very complicated reasons. And so, I essentially retired young from being a practicing clinician, and now I’m a full-time writer.

CC: So, were you writing the whole time you were seeing patients? Or —

LG: I was. And this was in the early days, this was back before everybody knew everything about everybody. It was essentially before everybody Googled their therapist. And so, I published my early stories as L.K. Gornick and they were in literary magazines, and there was essentially very little chance that any of my patients ever stumbled across them. When I published my first novel, and it was suddenly in bookstores, that became no longer tenable. And then eventually, you know, by the time we were in the aughts, every — my patients had access to everything that I was writing. And that began to feel inhibiting for me because, of course, I’d never written about my patients. And I was much more rigid about that than many clinicians are who seek sometimes permission from their patients to write about them, or write about them in disguised form. I had a very firm boundary. But what — as a fiction writer, what we write about really depicts our own inner lives, and so I ultimately felt quite exposed. So, it wasn’t that I was so much afraid of exposing my patients, that I had under good control, but as writer, my whole inner life was on display, and that did not feel compatible any longer at some point.

CC: Can you describe the synergy between the two, writing and psychoanalysis?

LG: Sure, I call them novelizing and analyzing. So, those fundamentally, as I said, you know, I learned with my very first exposure to therapy, which was sitting in on the inmates’ kind of rap session, they’re both really about telling stories. And in the therapeutic context, there’s a very important psychoanalyst, who unfortunately died recently, named Roy Schafer, who wrote a lot about the role of narrative in therapy. And one of his ideas was that what happens in a therapy is that patients rewrite their narrative, so that there’s essentially more room for autonomy, self-control, and choice. So, as a therapist and then as a psychoanalyst, I was really trained to hear unconscious themes, to see the way that stories unfold, and to hear the way that emotion is concealed in language. And so, I felt very much as though I was using what I knew as a student of literature in the therapy room, and I, the reverse as well. I feel very much as though I use what I learned as a therapist and a practicing analyst, in my writing in the sense of character development, the way I go about developing characters, in the way all of my books essentially are premised on a belief in the unconscious, that people are moved by unconscious forces. And that when they come to have a bit of insight into that, all kinds of possibilities open up. And also, in a theme that I have carried across all my novels, which has to do with the way that things in one generation that are not explicated or spoken about, then get played out in the next generation, which is really a theme in The Peacock Feast, the most recent novel.

CC: Yes, let’s discuss your most recent novel, The Peacock Feast. And, tell us, tell us in your words what the book is about.

LG: The way that I think about it is, I have a visual image of it as like a braid. The book is essentially structured around three story lines. The first strand involves this encounter that takes place between Prudence, who’s 101 years old, and her great-niece, who’s 43 years old. And it takes place over a week in 2013. And what happens is it’s a Sunday afternoon and Prudence, who is still quite well for her age, who lives on her own and is helped six days a week, but not on Sundays, when this book starts, by a caregiver, is kind of dozing in her apartment on the Upper West Side in Manhattan, when her phone rings. And a woman on the other end of the line identifies herself as her great-niece, or she believes she’s probably her great-niece. And that would mean that she’s the granddaughter of Prudence’s brother, with whom Prudence lost touch many, many years ago — 90 years before — when her brother, Randall, at 14, left home.

So, Prudence, who, like her name, is a very cautious person, sort of throws caution to the wind and says, “Sure, come up,” really not knowing if this is in fact her great-niece, but thinking, “What the hell, I’m 101. What difference does it make at this point? I’ve lived a long life.” And it is in fact her great-niece. And they begin this conversation that stretches over a week in which they tell each other their stories. And in so doing, essentially, flesh out for each other pieces of their family narrative that goes over a century and four generations, and begin to have a much richer understanding of what has impacted both of their lives. And they also form a very powerful bond. So, that’s the first strand.

The second strand is Prudence’s story, which begins with her earliest memory, which is of the Peacock Feast, the title of the book. And that is at the age of 2, she’s crouching behind the balustrade with another child watching these girls in Grecian togas parading across a terrace with silver platters hoisted on their shoulders. And it’s not until she’s an adult that she understands that this was what Louis C. Tiffany, who was the employer of her parents, called the Peacock Feast. That it was this very strange event, something between a spectacle and what we might call today performance art, that he threw for 150 men of genius — that’s what he claimed. He didn’t invite any women. And he brought all of these extremely famous men out to his Oyster Bay estate on a private train and served them this meal which included, in fact, roasted peacock that had been made by Delmonico’s. And it was a very strange event of which Prudence has this small memory. So, this second strand then follows her life. The next important event is when her family peremptorily, and for reasons that are always mysterious to Prudence, leaves the estate. Her father becomes Tiffany’s gardener at his Tiffany, at his Madison Avenue estate. And we then follow Prudence through her life. She becomes a decorator. She marries a wealthy man, who refuses to have children with her, and then dies young leaving her a widow. And she goes on to become involved with Tiffany’s youngest daughter, Dorothy Tiffany, who herself had a fascinating life. She was essentially Anna Freud’s life partner in work, and other ways. So, that’s the second strand.

The third strand is Grace’s story. So, there’s a symmetry because the first strand is the encounter between the two of them. And here, I made a kind of strategic decision which was to begin Grace’s story line with what Prudence doesn’t know about her brother and what has happened to him. And if you recall, her brother, Randall, left home at 14, so Prudence essentially knows nothing of his life. So, that third strand opens with Randall as he leaves home, and he stows away on a train to San Francisco. And we follow him through his first year in San Francisco, where he becomes an assistant to a florist through another boy that he knows, ultimately opens his own shop, and marries a kind of renegade society girl. And then like a baton passed from generation to generation, the book turns to Randall’s son, who is Grace’s father, and that’s Leo, who is born in 1948. And we jump fairly quickly to 1963 when Leo turns 15, and becomes — he turns kind of wild, as does the city, San Francisco, at the time in those years leading up to the Summer of Love. And he ultimately takes up with a runaway girl from Texas. And the two of them go to live on a commune up in northern California, which is where Grace and her twin brother, Garcia, are born. And it’s Garcia’s death, Grace’s twin, through very tragic circumstances that lead to Grace’s becoming a hospice nurse.

So, those are basically the three strands. And they ultimately play together as the two protagonists, Prudence and Grace, and then the reader, gain a larger understanding of what has happened in this family over a century, and four generations. So, as you can see, that is not an elevator speech but — that’s the best description I can give.

CC: Yeah, I would say, having read the book, I couldn’t do it much more concisely myself. So, one of the things I want to point out about the book is that in addition to being a novel, it’s a piece of historical fiction. And I’m just curious how you decided to take that on and what the genesis was for this particular time and these sets of characters?

LG: Well, I really never imagined myself writing historical fiction, though I had done some substantial research for my second novel, Tinderbox, which involved some things I knew very little about. It was not historical. What happened was that I had the idea of this first strand, this encounter between a very old woman and a great-niece she’s never known existed, before I started with that. And then one day, and it was now 12 years ago, I, by chance, happened to wander into an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art about Louis C. Tiffany. And essentially, I’d never been interested in Louis C. Tiffany or his work. I had the — a misimpression of him, that was because his work is over-used and replicated in all kinds of cheesy environments, and it had never particularly grabbed my attention. But when I went to this exhibit, I quickly learned that I had been very misinformed about him, and he really was an immense artistic genius. And his masterpiece was Laurelton Hall, which is the estate in which Prudence is born. And it was this mansion that he built in Oyster Bay, Long Island, at the beginning of the 20th century that had 84 rooms and — I think I have that right — and 588 acres. And it was this historical hodge-podge. There was a loggia that was modeled after the Agra Fort in India. And there was a fountain that was modeled after the Topkapi Palace, and the heating unit was housed in a minaret. And it was very fantastical. So, what captured my attention was a photograph of what I later learned was the Peacock Feast. And in the photograph there are five girls that are dressed in these Grecian togas. And three of them are carrying these silver salvers on which sit these roasted peacocks with their plumage reattached. And the other two are carrying bouquets of peacock feathers. And I became intensely curious, both about what was this event, and who were these girls? And it was when I discovered that three of the girls were in fact Tiffany’s daughters, and that the middle was his youngest daughter, Dorothy Tiffany, who I knew from my studies as a psychoanalyst as Dorothy Burlingham, who’d played a key role in psychoanalysis because she was Anna Freud’s partner in life and love, and a person whose money helped to get the Freuds out of Vienna in 1938 when they fled to London. So, once those aspects fell into place, I realized that I was somehow going to use that setting and those characters as part of this novel. So, in the novel, Prudence is born two years before this Peacock Feast at Laurelton Hall where her parents are a gardener and a maid. So, the book is an amalgam of imagined characters, Prudence and her parents, and then some historical characters, like Louis C. Tiffany and Dorothy Tiffany and Anna Freud, among others.

CC: The book deals a lot with loss. And I think that the loss comes through in the form of intergenerational trauma. I’m just curious, what do you hope that the book would teach a reader about loss?

LG: Well, I really never set out in my writing to teach anybody anything. I think that what fiction does is allow a reader to enter imaginatively into many experiences, and that may help him or her to be able to elaborate their own internal experience. And I think that that’s one of the reasons that we read. We read to recognize ourselves, often, in what’s being said or to understand other people who are, who are part of our lives.

That said, I think that loss is an intrinsic part of being human. And Mark Epstein, who is a psychiatrist and a Buddhist scholar, has written a good bit about this, even using the story, the historical story of the Buddha as a way of explicating it. That it’s really a misapprehension of the human experience to not understand that loss is not the abnormality, but it’s woven into our lives. We all die. We will, most of us, lose our parents. All of us lose people who are close to us. And if we’re not prepared psychologically to understand that as part of the pattern of life, then we’re going to have a lot of trouble.

That said, then, in this particular novel, what is at play is that there’s a great deal of loss that is repressed, not expressed, not even acknowledged. And for that reason, the characters suffer many kinds of consequences that they come at the end to understand might have been avoided, had they been able to more directly handle and deal with their loss.

CC: I’d like to ask you about your habits as a writer. What kind of — every writer sort of has their own set of ceremonies and idiosyncrasies. I’m just wondering, what are yours?

LG: Well, my habits have evolved over the years but — and often, life does not allow me to pursue them in their ideal. But I’ll give you their platonic ideal: In the platonic ideal, I would, at the very end of the day, look at and maybe read a few pages of the last thing I’ve written, go to sleep, and allow dreaming and unconscious processes to sort of interact with whatever is at play. Get up, I have a family, so I, you know, make breakfast, and send everybody off. And then I would have uninterrupted hours for four or five hours. And that is very challenging. That means that you have to not be on the internet. Not be answering email. Turn off your phone. Not have things pinging. But to really work without interruption for several hours. And then try to keep everything else — the business of publishing, talking to my agent, and emails with my publishing house, and all the family business — for the afternoons. So, that often just can’t happen, because life just won’t let — won’t permit that. But that is the ideal. And the other piece that I would add to that, that I’ve learned over the years is that my reading is a really integral part of my work. And I design my reading at times as part of my work. There’s often a phase of my work where I’m doing a lot of reading and taking notes and thinking, and I will do that during my, quote, “work time” because otherwise it’s not going to get done. And other writers, in reading what other writers to, and trying to understand and pick apart and analyze how their books work as they do, is really the main way that I learn.

CC: OK. Well, thank you so much for your time, Lisa, I really appreciate it.

LG: Oh, it’s been a pleasure, Carrie. Thank you so much for inviting me.

CC: Thanks so much for listening to this month’s PAWcast. If you’d like to hear other episodes, please go to paw.princeton.edu or subscribe on Apple iTunes. Till next time.

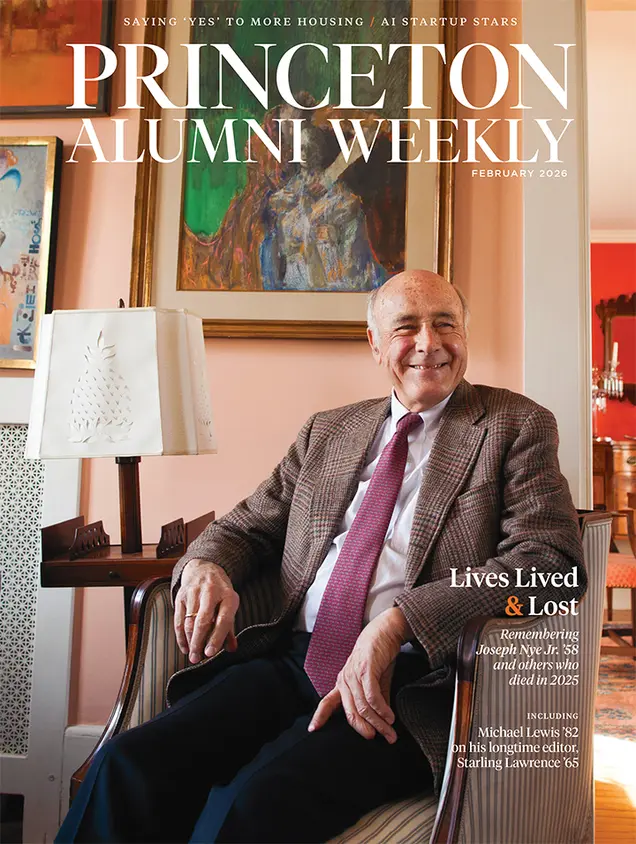

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet