PAWcast: Cara Jones ’98 and Her Father Farley Jones ’65 Reflect on Their Divergent Experiences as ‘Moonies’

‘There was some deep conflict happening through my years at Princeton,’ says Cara Jones ’98

Find more PAWcasts online here

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

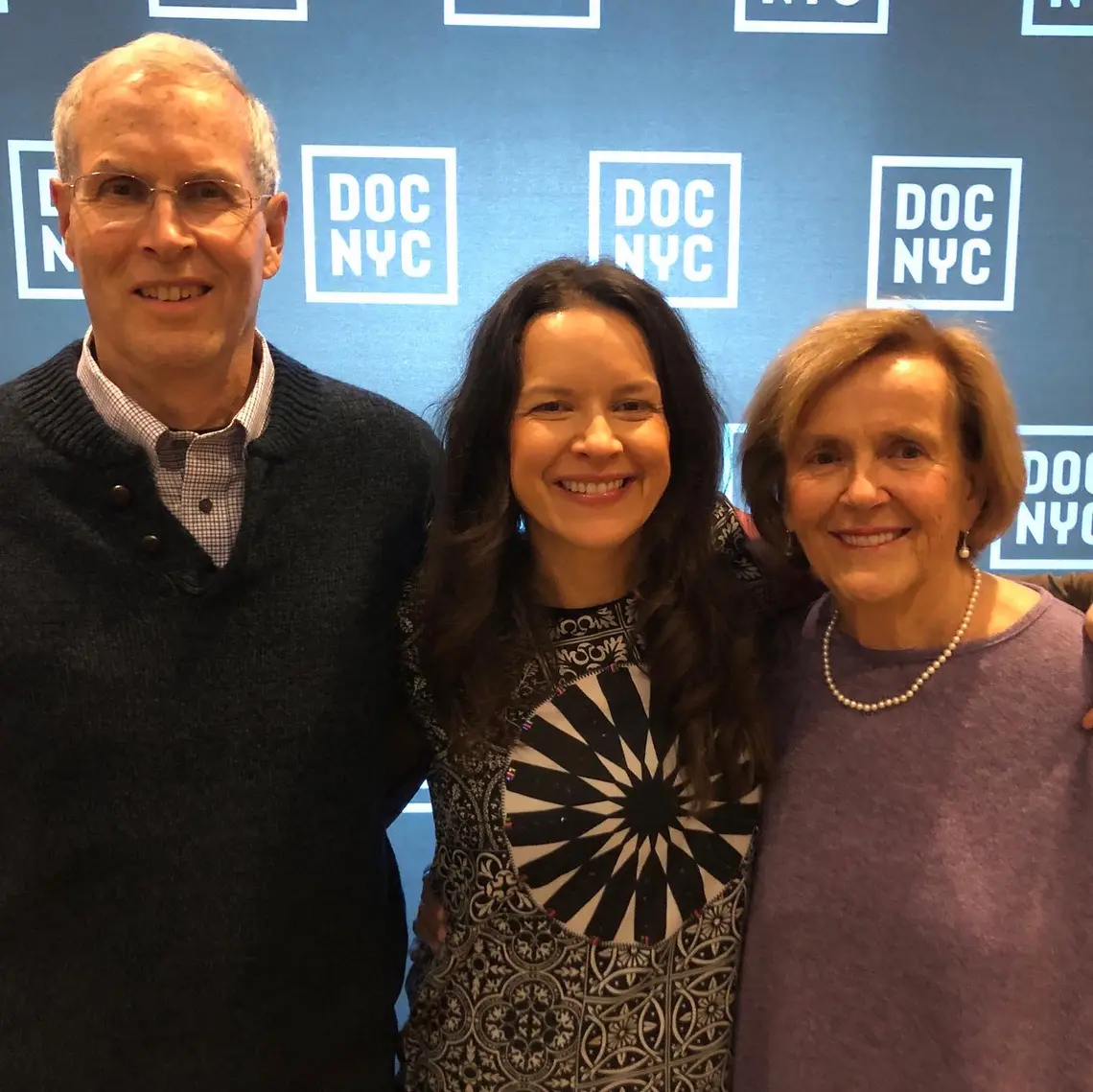

This month, Cara Jones ’98 and her father, Farley Jones ’65 discuss their relationship with the Unification Church created by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon. Cara grew up deeply devoted to the religion, like her father, and accepted a marriage arranged by the Rev. Moon. But in a new documentary, Blessed Child, she explains how that marriage ultimately led to her disillusionment with the religion and her decision to separate from the church.

TRANSCRIPT

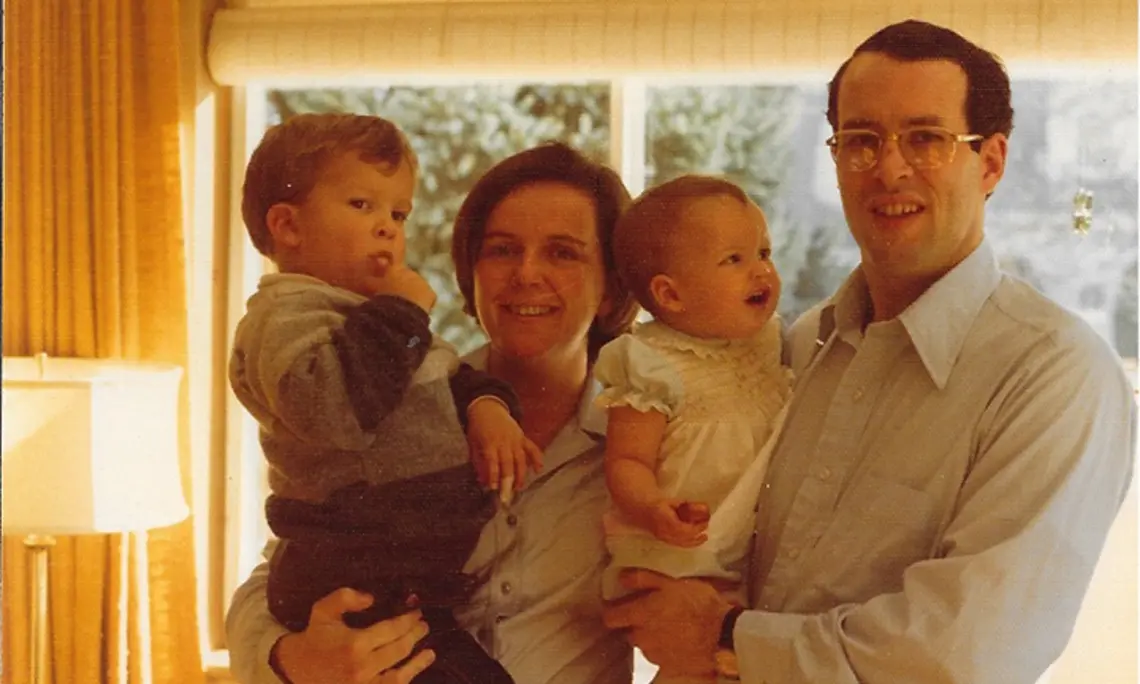

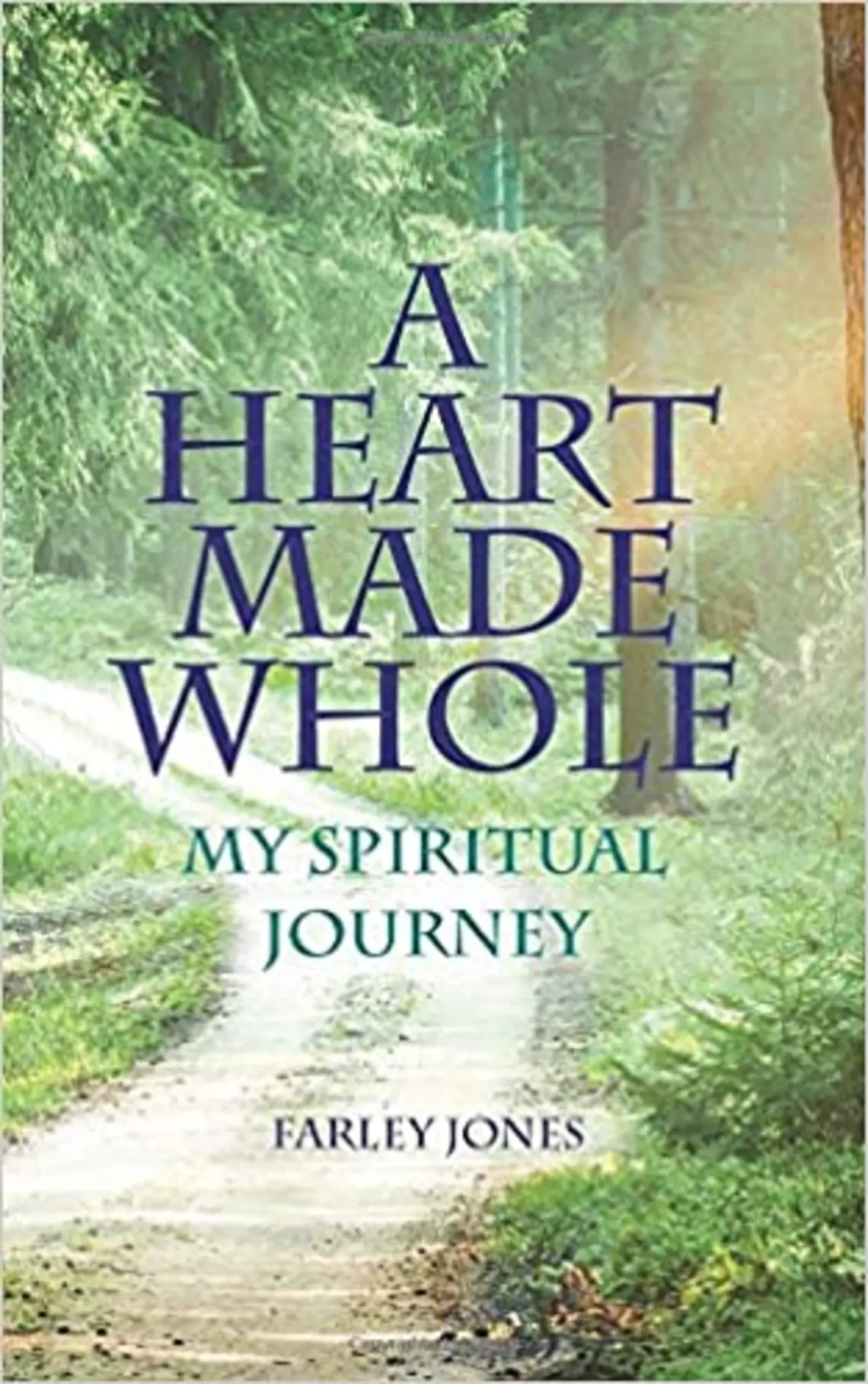

CARRIE COMPTON: Hello and welcome to the PAWcast, I’m Carrie Compton. This month, we’re speaking with Cara Jones from the Class of 1998 and her father, Farley Jones, of the Class of 1965. A couple of years after graduating from Princeton, Farley was introduced by a friend to the work of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, who believed his teachings were meant to complete the work of Jesus on Earth. Soon, Farley became a member of Moon’s Unification Church, one of several thousand so-called Moonies. Farley, who is now an elder within the church, writes about his experiences with the religion throughout his life in a new memoir called A Heart Made Whole. His second of five children, Cara, grew up deeply devoted to the Unification church and was delighted when the Rev. Moon had decided to match her to a husband at age 20. Her documentary, Blessed Child, now streaming on Amazon, is about how that marriage ultimately led to her disillusionment with the religion and the complicated family dynamics that came with her decision to separate from the church. Cara and I begin the conversation and Farley joins us midway through.

CC: Cara, thank you so much for joining me today.

CJ: Thank you, Carrie. It’s really nice to be talking with you.

CC: Likewise. Cara, your film begins with the story of your wedding, which took place alongside hundreds of other couples, including your brother and his wife, who were also entering into marriages that were arranged by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon. Your participation in this rite of passage was sort of the culmination of a life of devotion to the Unification Church. Talk about your life at that particular time. You were 20. So you were young. And you were at Princeton. How did that look from your perspective?

CJ: Yeah. So I was 20 years old. I had done my freshman year at Princeton, and I was very much devoted to the faith at the time. The year before that I had taken a leave of absence from Princeton. So I had done my freshman year. I was very much approaching my education as a path to do good in the world on behalf of the religion that I was raised in. And I was not into the party scene. I lived in the all-women’s dorm, 1915 Hall, at the time, and after my freshman year, there was this invitation from my church to do a year of mission work. And so I spent that year in Chicago teaching the teachings of the church. And so I was very much in the mindset of the religion I was raised in, which was that every person is a child of God and whoever you’re matched to is yours to love. And if you struggle to love them, then that’s part of the spiritual path of evolving your heart to grow. And so at the end of that sort of mission year away, I had been matched by Rev. Moon using 8x10 photographs with some personal information on the back. And he had matched me. And I got a call from my parents and found out who it was. I didn’t know him. I knew of him. I had seen him. He was somebody whose family I was familiar with, but I didn’t really know him. And so a month or so later we stood in the Seoul Olympic Stadium with 10,000 couples and committed to being married.

CC: Did your Princeton roommates know about your religion? Was that something you kept secret, or were you forthright about it?

CJ: So I was open about it. I didn’t wear it as a sign around — so I lived in an all-female dorm where everyone — I didn’t have roommates. I had singles. But those of us in our six-person singles unit all got to know each other pretty well. And as I got to know people I would share with them more about the faith and the upcoming marriage. And I know that there were some concerns on behalf of my friends, knowing that I was going into this. But they didn’t say much at the time. And when I came back I was a sophomore. So I slowly started telling people, again not leading with it, that I was actually married. I didn’t wear a ring. I didn’t want to make such a big deal of it. But I remember the year after I was a resident adviser. And I had to sort of announce that I was married. And it was a hard thing because it was so hard for most people to understand. I felt like I had to almost pretend that I was really in love and when he would come to visit that I was really in love because people otherwise wouldn’t understand, why would you get married so young? And yet here was somebody that I didn’t know that well that I wasn’t attracted to and yet I felt like I had to kind of put on this front. So there was some deep conflict happening through my years at Princeton.

CC: And where did he live while you were at school?

CJ: He was actually on his mission year.

CC: I see.

CJ: The year that we got back. And he was a few hours away. So we would see each other every month or so. But obviously weren’t living together or anything.

CC: So eventually your marriage fails. At least from the documentary it seems as though the failure of that union was a significant turning point for you in the church. Is that correct? And how so?

CJ: Yeah. Well, there was a number of things happening at the time. I think I had grown up with the expectation that I was going to have an arranged marriage. I didn’t drink. I didn’t date all the time leading up to this. And if I’m honest — if I was more honest with myself at the time, I think despite all the open-mindedness that I brought to the table, there was expectation that I would be able to fall in love with the person that I was matched to and that somehow I think I had a somewhat naive understanding of — you know, that it was all going to work out. Even if it was hard, like we would grow, and it would be beautiful. And this is a very wonderful person that I was matched to. But that wasn’t happening for me. So whereas before I could see myself following the path because my family was in it and all my friends were in it and I had some amazing experiences growing up in it, all of a sudden not feeling like I loved this person or could — yeah, it just made me start to look at things differently and question things. And at the same time that that was happening, Rev. Moon and some of his family, who I had looked up to, some news was coming out about one of his sons that I had looked up to having a drug problem, abusing his wife. And all of a sudden this picture of this ideal family that I had built up in my head and my own ideal marriage filling in — falling into this picture, which is all very naive, started to crumble at the same time. So it was a bit of a perfect storm in that regard.

CC: Interesting. At what point do you formally walk away from the religion?

CJ: You know, when you’re born into a religion, you don’t like sign papers on the way in or on the way out.

CC: This is very true.

CJ: And so if — I think honestly the making of the film was a more official leaving for me. I mean I left the marriage when I was 25. At the same time of leaving the marriage, which is why it was so painful to leave — it felt like divorcing my family and community at the same time. So that was a very painful time in my life. And so even though I left, there were ideas about myself and unresolved things with my parents that I held onto and kept me tied in some ways to the past and to the faith in more ways than I was even conscious of. And it wasn’t until I was in my late 30s and feeling the sense that I really wanted to have a family — and for some reason I couldn’t seem to figure that out — that it occurred to me that I had some unresolved business to look at. And I was at Burning Man in 2012, trying mushrooms and ecstasy, a very different world. My dad is listening to this conversation. So I don’t know if he knows that part. But in a very different world than what I was raised in. As I was driving out among all these dusty cars, when my text reception or cell reception kicked in, I started getting these messages like, “Did you hear Rev. Moon died? Rev. Moon died.” And interestingly he had appeared in one of my mushroom trips. So it was just this uncanny occurrence. And as soon as I got the news, I just felt this wave of now’s the time to tell this story. And — because I had been thinking about it, but I didn’t really have a reason to start doing anything. And when I got back from Burning Man, I had talked to my parents. And I found out that they were going to Korea for the funeral of Rev. Moon. And it felt like this decision point. If I’m actually going to make a film out of this. Because I had experience as a short filmmaker, in the five- to seven-minute range and had had a sense that there might be a documentary to explore here. And when I found out they were going, I just felt like I needed to be there and commit to telling the story. And so I called somebody who grew up in the church as well, who had also left, who’s a cinematographer. And I texted him, “Would you be willing to go to Korea tomorrow?” Or it was like within 48 hours or something like that. And he said yes. And then the film unfolded from there.

CC: Wow, so you’ve been making it since 2012.

CJ: Yes. Seven years. So I wanted to clarify. I don’t feel like — I mean I left the church in my mid-20s technically. But I feel like there was ways that I was holding onto it. And that I — and so that it wasn’t until Burning Man — not so much — it wasn’t that at Burning Man I had decided to leave the church. It was at Burning Man that I decided to answer the call to tell the story. And it was the telling of the story that helped me see the ways that I was holding on and let go more fully.

CC: Well, I just — I have to say, you answered one of my questions in there because I had planned to ask you whether the making of this film was cathartic. And the reason why I wanted to ask that was because you radiate catharsis throughout the entire story. So I definitely think you have succeeded in your mission there.

CJ: The other thing I wanted to say about catharsis is — because I do work with people around telling their stories. And there is a cathartic element of getting the story out, but for me the healing part hasn’t been so much about getting the story out. It still kind of makes me cringe honestly to watch it. But it’s that I got to have a more honest relationship with my parents and with myself. That’s the healing for me.

CC: This might be a good place to bring in Farley. Farley, what do you think? Did you get that same feeling of relief coming off of Cara? It must’ve been complicated for you, watching the film.

FJ: Well, yeah, it was complicated. Because this is not what — my wife and I were early members of the church and well-known within the church. And our family was well-known and respected. And this is not what was expected from somebody coming out of the Jones family in our history of the church. But I always felt this is something that Cara needed to do. And it was, as you said, cathartic. I think I would have seen — I think I did see it in terms of her need to work something through in a process of healing what her experience had been with the church and with her marriage. So even though it was complicated and we had, you know, honestly mixed feelings, I think both my wife and I felt like, OK, we’re going to support this. And we did. And we did. Yeah.

CC: Are any of Cara’s siblings still in the church?

FJ: Her older brother has, I would say, a degree of affiliation with it. His wife is Korean. But other than him, there’s not much interest on the part of our children right now. Our youngest son has some interest, but there’s no formal affiliation there.

CC: I see. So, Farley, was there anything you wanted to respond to?

FJ: Well, I think I learned a little more about the pain of Cara’s experience at Princeton. I didn’t realize that it was actually coming — I knew she had been to Burning Man. I don’t know how much I knew about the mushrooms. I might have known something, Cara. And I do remember you mentioned that you had seen Rev. Moon in one of those experiences. But I didn’t know that was really the time when you felt like you made the decision to step away from the church. I felt you had done that before, honestly. I thought that was pretty clear. But anyway, other than that, I don’t know, it was good to hear your questions, Carrie, and Cara’s answers.

CC: Yeah. Well, and I think it’s also refreshing for me, too. We’re living in such a divided society as a nation. And so to talk — see two people who are close to each other being able to talk about something that is so meaningful to both of them and for both parties to have such an accepting nature is really — speaking of catharsis — is very cathartic for me, I think.

FJ: Yeah. Yeah.

FJ: So — yeah, so Rev. Moon comes out of a Presbyterian background. He had an experience with Jesus when he was, he says, he reports, I accept it, when he was 16 years old. He felt called to his mission from that point. And he embarked on a spiritual search and ultimately produced a systematic theology called the Divine Principle. Simply said, the Divine Principle teaches that God’s intention in creation was to create a world in which loving relationships prevailed essentially between man and woman and parents and children, within the family. It’s a very family-centered theology. And from his point of view, that true family, which is one of the well-used terms within the church, the true family was to be established through the original parents, the Biblical figures of Adam and Eve. That, as any Christian will tell you, was not realized. There was the fall of man. So Rev. Moon understands that Jesus came as the second Adam and that Jesus’ mission was to take a bride in the position of a second Eve and establish the true family that was meant to be established at the time of Genesis. But because of the crucifixion, that could not be realized. So then Rev. Moon understands himself as being anointed as a third Adam, in a position to establish a true family which would be the seed. The true family would be a seed of the true society, true nation, true world: the Kingdom of God on Earth. That’s the vision. And that’s the heart of the teaching I think.

CC: So in your book, you used some pretty bleak language to describe the kind of child that you were and a sort of sadness that followed you into young adulthood. Speaking of your time at Princeton, I believe you described yourself as “a lonely loner.”

FJ: Yes.

CC: Not all loners are lonely. So I think that’s an important distinction. But after you find the Rev. Moon’s teachings, your language does decidedly become more optimistic and vibrant. Do you ever imagine what your life would have turned out without taking this path? And how is different from the life that you’ve found?

FJ: I mean, I think in my case my encounter with the Divine Principle and the Unification Church and Rev. Moon has had a — not to put too strong a term on it, but in my mind has had a salvific effect. I don’t think I would have had a happy, satisfying life if I hadn’t met — if this hadn’t come across my path. I just don’t think I had the internal substance that I would have needed to make my life a happy and satisfactory one. Yeah.

CC: So you became an adherent early, as you said, in the very late ’60s. But by the time of the ’70s is sort of when there became almost an urban legend around the so-called Moonies and children disappearing from families. And there was a lot of hyperbole and tabloid-like stuff. What did your family think about your choice to become part of this religion?

FJ: You know, we never had extended conversations about that. I know my mother was uncomfortable. She once thought that — said something that she thought Reverend Moon for some reason — I don’t know why she said this. She thought he would lead us or somebody into war.

CC: Oh, wow.

FJ: Yeah. I guess she saw him as a strong leader, which he was, and associated that with other dominant leaders, for example, Hitler. Well, people thought of Rev. Moon in those terms in those days. At least some people did. My father had I think a bigger view of it. And I think he was more concerned about the kind of life that I was going to lead given the sacrificial kind of lifestyle that most members lead. He once said to me, “I hope you’re not going to end up living in some Bronx tenement.”

CC: And you’re speaking there of the obligation to do mission work unpaid, correct?FJ: Yes. Yeah. Yeah. But that said, they never explicitly opposed what I was doing or tried to dissuade me from it. However, my parents were very hands-off in the way they raised me.

CC: So, Farley, something that I come back to over the times that I’ve watched Cara’s movie is that you — you are pretty forthright about the fact that there are some problems with the religion. There are some things that you wish that would be reviewed, for instance, homosexuality. But you say it’s not perfect, but that you can look at the journey and you can say to yourself, “I am where I am today as a result of this, and that’s kind of good enough for me.” It’s funny because Cara very much has got the same thing happening for her, except the religion part just isn’t there, right?

FJ: Right.

CC: How does that make you feel?

FJ: Well, no, it — my faith worked for me. It didn’t work for Cara. I accept that. Over the years, frankly, one tends to be able to see things with more — in less black-and-white terms and noticing more shades of gray. So I accept our church is not going to work for everybody. That’s for sure. And it doesn’t need to, I think.

CC: Cara, I’d like to hear your thoughts on that. What do you think?

CJ: Yeah, I think that’s been what my dad described was the journey of my own acceptance in the film. I think because we were such a close family. Because we were such a close family and the religion was part of that when I was younger. There was — long after I left the church there was a sense that without that faith and me marrying someone in the church or having that connection, that we wouldn’t be able to stay connected in the same way. That it would never be as close. And because I love my parents so much and it did work for them, there was the sense that it should work for me. And some of the liberation for me in telling the story was about that acceptance. That actually understanding more deeply, it actually did work for them. Because I also went through a phase of thinking, “Well, maybe my parents are just deluded, and I need to get them out.” And so making the film and having these honest conversations helped me understand that it actually did work for them, and I don’t want to take that away from them. And that doesn’t mean that it has to work for me. And that doesn’t mean that we can’t find a deep relationship. And I think what emerged for me in this making of the film and the numerous interviews that I did with my parents over time was an honesty — at least on my side, I felt like I wasn’t being 100 percent honest or asking honest questions. And I feel like I grew in my ability to be more honest with them. And that the relationship that we have now feels more honest to me and deep to me, because of that honesty, in a way that is not about the religion but just about the relationship.

CC: About being a family.

CJ: Yeah.

CC: Is what the whole religion is about, funny enough, right?

CJ: Yeah.

CC: All right. Well, Cara and Farley, that is the end of my questions. I want to thank you both for being game for this and being so open and honest.

CJ: Thank you, Carrie.

FJ: Well, thank you, Carrie. I thought you asked great questions, honestly.

CC: Thank you. Thank you.

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet