PAWcast: Kush Choudhury ’00 on Journalism in India

The author and visiting professor discusses a media ecosystem shaped by ubiquitous connectivity

Across the globe, journalism and press freedoms are in peril. However in some countries, the internet — which is blamed for the declining revenues of traditional media in the U.S. — has aided poor populations who previously could not access news for free or communicate easily with the rest of the world. Kushanava Choudhury ’00, who was a Ferris Professor of Journalism in the fall, discusses the media ecosystem in his native India, where he was a newspaper reporter for several years. In addition to the positive effects that have come with ubiquitous connectivity, he discusses how internet-based misinformation and governmental propaganda are able to pass as legitimate journalism, and why it’s likely to end.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: Hi, and welcome to the PAWcast. I’m Carrie Compton, and with me today is Ferris Professor of Journalism Kush Choudhury, Princeton Class of 2000. Kush has extensive experience as a reporter in the United States and in India. After emigrating from Calcutta with his parents at age 12, he had always longed to return — and once he graduated from Princeton, he did just that.

Back in Calcutta, he took a job reporting for a well-established English newspaper called The Statesman, which, at the turn of the 20th century, had the largest circulation in all of Asia and still held enormous sway within the city. In 2017, he published a book called The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta, which is part memoir, part reportage about his beloved, and in some ways broken, hometown.

This semester, Kush has returned to Princeton as a lecturer in the journalism program. Kush, thank you so much for joining me today.

Kush Choudhury: Thanks for having me.

CC: Let’s start with the question that everyone is dying to know. How does it feel to be back in Princeton? (laughter).

KC: Well I just finished teaching yesterday, and so it feels great, that part of it, you know. It’s been a very emotional experience to be back.

CC: How so?

KC: Well, I taught the class that I took 20 years ago with John McPhee [’53]. It was called “The Literature of Fact,” and I was one of 16 students in the spring of ’99. And that course really set me on the path of becoming a writer. And so to come back 20 years later and teach that class to a group of, students, is a tremendously powerful and I think it’s an emotional experience. Because you are returning, but you are also not returning to the same place. You are hoping to propel others in the way that you were propelled when you were in their position, right? And you don’t know what you’ve done, because you won’t know for another 20 years.

CC: Talk about your writing career after you left Princeton, and how that’s kind of worked itself out.

KC: Well, so yeah. I graduated in 2000, and I went to Calcutta to work for this paper — The Statesman — that you mentioned, and at that time it was still the largest paper in India — in Calcutta — maybe in all of Eastern India. But largest English paper, you know. But it was a paper in decline. It was slowly kind of — it was not able to attract new readers, the economy of the country had changed, or it was changing. And the paper was not able to kind of keep up with those changes, because they were changing the media landscape as well.

So it was a dying paper — and the city of Calcutta was seen as a kind of dying city. It had been the capital of the British Empire until the 1970s. It was the largest city in India, it was the industrial center of India. It was seen as having had the best universities, the best institutions, in many ways. But it was no longer the capital of India, it wasn’t even the industrial capital of India. It was a post-industrial city. You know, the factories had largely shut down for about 20 years. And it was a city that people were migrating out of, by and large. Most people who were — I had a lot of family in Calcutta. I still do. And most of the people in my generation had left, or were trying to get out. So I was coming in the wrong direction.

CC: Yeah, yeah.

KC: Yeah. And then —

CC: So you worked there for how long?

KC: Two years. And then I left, and I came back to the U.S., and I went to grad school — I did a Ph.D. in political theory at Yale. And I did that for about five years. But I had this idea of writing a book about Calcutta. And so I would keep going back in the summers. And then at the end of that, I had a fellowship for a year. And then that’s when I went back. And the book that I wrote is really about — it’s set in the framework of that year. And I spent that year reporting on various parts — aspects of the city — things that I felt had kind of escaped me as a reporter.

CC: So talk about what the newsroom looked like at The Statesman when you returned in the 2000s. And then let’s talk about what it looked like when you went back the second time for your fellowship and you took a little tour.

KC: Yeah. Well the newsroom — the newsrooms were like (laughs) — I think all newsrooms were like — first of all, you could smoke. I mean, everybody smoked.

CC: Yeah.

KC: And the people who weren’t smoking might as well have been smoking, because, you know —

CC: Right.

KC: — they were surrounded by smoke. These are air conditioned, closed rooms where you’re sitting there all day surrounded by people who are smoking. I just can’t imagine then — I used to smoke. But not only did you smoke, but you couldn’t imagine putting out a newspaper if you didn’t smoke. I mean how are you going to write? Like, you know? You know, the whole — the synapses would not fire (laughter) if you weren’t like constantly smoking. So it was that kind of a — smoke-filled, a lot of like very macho kind of places, you know — newsrooms.

CC: Yes.

KC: A lot of, guys cursing, and, very male —

CC: And there are a lot of guys, right? Not only just men, but also bodies. I mean the newsroom you describe in your book — it sounds like you’ve got people everywhere.

KC: Yeah.

CC: It’s not that way anymore.

KC: No, I guess it’s not. Yeah. There’s people everywhere — and people coming through, also. There was this whole culture of like around 5 o’clock I write about that — when work, offices are kind of shutting down. A lot of times, people just come in to the newspaper office and hang out.

CC: Yeah.

KC: People who worked in, in the city government — people who were — whatever — hang-abouts, you know. And then you would kind of have this kind of salon going on in the newsroom. And then sometimes that would move onto a bar.

And at the time, the paper also had this like huge other infrastructure, which was that the newsroom was only a small part of the hundreds of people that worked at the paper. There were people who were like gophers, like peons, literally whose job it was to take papers from one room to another room.

CC: Wow.

KC: There were like cooks, there were — these waiters would come and serve you tea. There were just hundreds — liftmen, elevator operators, guards — and a lot of these guys had been — they’re like the third generation. You know, their fathers had done it, their grandfathers had done it. So, it was almost like a fiefdom that they were running, which is one of the reasons the paper declined, because you had to pay a lot of salaries.

CC: So what happened when you went back? How many years later was that?

KC: So when I went back in 2008 — this is, what, maybe five years later? Yeah, five, six years. Not a long time later. But the building had become a shell. It looked like those shells of factories you see, even here — if you go into any of these post-industrial cities like Trenton or Philly — you see these shells of factories just — a structure that is up, but there’s nothing. You look through and there’s nothing inside.

CC: Yeah.

KC: And that’s what the building looked like, because they had leased it to a foreign company to build a mall, but then they had all these issues with permits. So they had torn down all the walls and all the, all the stuff inside, but they hadn’t rebuilt anything. So you would, walk through basically the shell of the old Statesman building, and all the way at the very top on the topmost floor, they had held onto a couple of rooms, which is where the newspaper was.

CC: Wow.

KC: You know, and it was like essentially walking through a metaphor of the newspaper. (laughs).

CC: Yeah. Yeah.

KC: It was tremendously depressing. I think I went there maybe once or twice, and then I couldn’t bear to go back. People often ask me, “Is The Statesman still around?” It is still around. But it couldn’t keep up. I think — it remained something — newspapers changed in India. They became basically vehicles for selling consumer goods, selling real estate, and selling a certain kind of lifestyle, you know. Which, from the ’90s, globalization kind of came to India. And it came to Calcutta a little bit late, because Calcutta had a communist government. Also, it was a city in economic decline. You know, like I said, the factories had shut down, there wasn’t a lot of manufacturing happening.

But still, that wave eventually came to Calcutta by the 2000s. And the kind of media that came with it was very different. That media had to be a vehicle to sell you things, you know? That was the main reason for its existence. So you see things like, the other newspapers will now have not only advertisements on their front page, but they will have like a covering page on top of the front page, which will be a full ad, say, of a new high-rise apartment complex, right? So the front page is really, an advertisement. And then you open that, and then the second page is the front page, which might have some news. But the way that that structures how reporting happens, is very clear, which is that the advertising drives the reporting.

I think the first paper to figure that out was The Times of India, which is the largest paper in India. And they were very open about it — that this is the model that we have. And other papers have kind of tried to figure out how to follow that model.

CC: So when you say the advertising drives the journalism, do you mean that advertisers are pitching stories, approving stories?

KC: I mean, and that happens I think in different ways — it happened even in the old newspaper system. But what happened, I think, since the ’90s, was much more sophisticated, which is that if you understood what the interests of your advertisers were, then you would report accordingly, right? So there were things and people — there were subjects you would not touch, and there were people you would not touch.

CC: OK.

KC: And what has happened now, politically, which is very interesting, is that there are political figures you don’t touch, because they are connected to your advertisers. And so the politicians don’t have to directly tell you not to write about them. They can just lean on their corporate supporters, who will then pull out their advertising.

CC: So the watchdog function has all but been abandoned?

KC: Yes. And it’s a very interesting way in which the watchdog function has been abandoned. There’s a senior politician who used to be with the ruling party, but now is like a disaffected, kind of independent voice, you know. He’s — oftentimes, he will say things which are — other people are afraid to say. He said, “There’s an old Zulu proverb that if you want to shut up a dog, you just put a bone in its mouth, and that’s what happened to the media.” You know, you don’t need to muzzle it. You just need to put a bone in its mouth.

CC: Right.

KC: And so it’s very interesting, because the media’s thriving, you know.

CC: Interesting. All forms?

KC: Yeah. Well, the print media — I mean compared to the U.S., it’s thriving. The T.V. media is thriving. I mean, right now, at this present moment, the economy is not doing as well as it was doing a few years ago. And so there have been some cuts, and this and that. But by and large, you have expanding readership. And also the fact that these are vehicles by which, advertising happens means that, there’s a lot of advertising. There’s a lot of advertising money, that continues to be poured in. It’s not at all like the picture of newspapers and print media in this country.

CC: Yeah, right. It’s interesting. It’s like what we used to have, just minus any real teeth.

KC: Yeah. So that’s the interesting thing, you know. In the ’70s, there was a period called “The Emergency” when newspapers were censored, where democracy had been suspended. And at that time, the newspapers used to have to go through censors, and you would see, you know — things would be blacked out or cut out and you couldn’t publish — so none of that is happening right now. There’s no official censorship of newspapers. But there is clearly unofficial censorship that is going on. And sometimes when somebody breaks the rule, you see the consequences very quickly.

It’s a big country, and the media landscape is very large. So there are media outlets who are not doing this because their funding sources are different, or because they have an ideological position of doing journalism. And so one, you find, for instance, certain regional newspapers who have their own kind of advertising resources or sources, that are not connected to the ruling party — often connected to other parties — are able to function. Then you have certain online media outlets now that have money from foundations or nonprofit sources of funding, so they’re not reliant on advertising, that are doing very good journalism. You have a few other media outlets, like the one that I used to work for, called The Caravan, which is a long-form magazine that has done a lot of really good stuff. And I think the reason that they’re able to do it is because they’re much smaller, and are not reliant on very large corporations for their funding.

CC: What’s the state of television media? Do you have a CNN and a Fox News, for instance?

KC: Yeah, that’s really funny. Yeah, there is. There is a CNN and a Fox News, but it’s like CNN and Fox on steroids (laughs), because they have the TV screen — I think here, usually they’ll like partition it into three sections, with three guys —

CC: Sure.

KC: There they’ll partition into like 12 (laughter), you know. And —

CC: It’s like Hollywood Squares.

KC: Yeah, exactly. It’s like Hollywood Squares. And just people yelling. There’s like 12 guys who come on, and they’re just yelling at each other. And, and it’s just a show. I mean it’s just completely — some of those guys sometimes —they’re like — the Harlem Globetrotters used to play the Washington Senators, and those guys are like paid to come on and look like fools, right? And there are people like that, who come on these shows at night, who are paid to look like fools.

CC: Oh, interesting.

KC: I think that there are elements of that on MSNBC and Fox, but it’s just that on a much more exaggerated scale. There are a couple of shows that don’t do that — there’s a guy named Ravish Kumar who has a show on NDTV in Hindi, which is very courageous. He himself I think has done a lot of, excellent reporting. But those people are constantly targeted. I mean, I mean he’s faced death threats. There are various ways in which his reach has been kind of limited in the last five years.

But by and large, this is what the TV media landscape looks like. And the people who have been very successful in it are the people who have been the most circus-like, and who have played into the most sort of unthinking, jingoistic, impulses of the public. You have to — if you’re on 24-hours a day, and you’re screaming all the time, you have to just be more and more outrageous, to get people to watch you, you know? So I don’t watch the TV news, because when I watch it — it’s funny, because when I — sometimes when I’ll turn on the TV news, I just can’t believe that people are watching this, you know? (laughs)

CC: Right.

KC: It’s like (laughter) how can you possibly bear to watch this? This is crazy. Like, like nobody in real life, sits in a room with like 12 people who are just yelling at each other, you know?

CC: Yeah, right. So describe social media. In what ways has that transformed the landscape? Is it keeping people better-informed? How does it work there?

KC: Well, look. There’s good things that have happened with social media I think, in the same way that they’ve happened here. One nice thing about social media is that it’s global, you know. So something that is happening in Turkey and London and New York — in Delhi — are all happening at the same time in the same space, right? So the way that that plays out, for instance when the #MeToo movement started happening here, right, there was a whole social media explosion of #MeToo stuff that happened in India.

CC: No kidding?

KC: Yeah. And in India, it wasn’t mostly to do with people in the film industry. It was other industries, including the media. So I think, I don’t see how that would have happened without social media because one of the challenges with a story like that, I think, that traditional media has is that traditional media is beat-based, and that beat doesn’t exist, right? There’s no #MeToo beat. So you don’t have anybody covering that, and therefore it doesn’t exist as a story. And so there are positives. But there are also huge negatives, which is that social media has been — it allows in the same way that it allows here — it allows political leaders to basically bypass any media and just directly tweet. So the Prime Minister in India just tweets — he doesn’t hold press conferences. I have friends who say, “It’s really hard to cover the ministries, because the Prime Minister’s reporting on your story before you get a chance to report on it.” (laughs)

CC: Right.

KC: Right? But he tweets, and he does radio programs, where they’re not like call-in, it’s just him talking, you know. It’s a one-way communication. And so you can amplify your voice in an unmediated way — in the same way that Trump can here. But the other thing of it is is that you can spread rumors and misinformation just much more effectively. And you can organize people around these rumors. You can create mobs, for instance, you know. I mean — here I think, like flash mobs are this like quirky thing where people, like get together and dance or whatever it is. But you can also do that to be like, “Let’s get together and lynch somebody.” And that has been happening, you know.

CC: So which forms of media are they — social media — are they interacting with the most?

KC: Twitter — and WhatsApp. WhatsApp is huge in India. Everybody has WhatsApp.

CC: Yeah.

KC: And WhatsApp is used in a way that it’s not used here, where lots of — I mean if you exist, you need to have WhatsApp. So I don’t have Twitter or Facebook or any kind of social media. I’m pretty much a dinosaur in that way. But I need to have WhatsApp, because if you’re doing any kind of work, a lot of that will be done on WhatsApp. People will send you documents on WhatsApp. They’ll like, text you on WhatsApp. Sometimes if you have to interview somebody who’s not there, you’ll interview them on WhatsApp. You’ll call them on WhatsApp. Because it’s all free, right? So lots of interactions happen on WhatsApp. And, until recently, there was this perception that WhatsApp was not being monitored. Because you have the whole idea was that there was end-to-end encryption, so you couldn’t monitor what was being sent over WhatsApp. That’s not true now, because I think there’s like this Israeli company that’s hacked WhatsApp. So a lot of political groups would also use WhatsApp, because there was this idea of privacy. But WhatsApp is — I mean, if you’re living in India, like you wake up in the morning, and your elderly, retired relatives will send you “good morning” messages on WhatsApp every morning.

CC: Wow.

KC: You know? With like a photograph (laughs) of a sunrise, or like a smiling baby or something, you know?

CC: Yeah.

KC: And then they’ll send you like little videos of whatever …

CC: So one of the things that’s also affecting America and India alike is press freedoms. How is that going, now that we have Narendra Modi and his quite-authoritarian regime in power?

KC: Like I said, there’s a huge curtailment of press freedom. Look, there’s always been media that has been close to power. In every country, there’s media that is close to power. But there’s — when Modi came to power, what happened was, even before, when the congress was in power, there were journalists that you knew were sort of congress journalists, that they were pro the government, right? But now you have almost a whole section of the media that is blindly a cheerleader of this leader. And there’s largess, you know. There are things to be gained by doing that (laughs). And so there’s a very special kind of relationship.

There’s a word that Ravish Kumar — the journalist that I was talking about who was on NDTV — has a word in Hindi called Godi media. Godi literally means “lap.” So it’s like not watchdog media, but lapdog media. These are media people who are like lapdogs of the state, which I think is exactly right. And so there’s a big contingent of people who are like that. You know, when Stephen Colbert used to be on, he would often have this thing, he was like, “Bush: Great president, or Greatest president?”

CC: Yeah.

KC: You know? (laughs) And there are books like that that keep coming out. Which means that there are people who are willing to write them, and then there are people who are willing to publish them, right?

CC: And people willing to read them.

KC: And people — of course everyone’s willing to read them, yes. And then the rest of the media I think, by and large, knows that you go along to get along, because if you are openly critical — you can be critical of things at a lower level — at the state level, or at the levels of lower government — but if you’re critical of Narendra Modi or Amit Shah, then — and at one point Arun Jaitley, (who were the number one, two, three), then you will have consequences. And it could be that there will be an income tax rate on your house, or on on your media establishment, or it could be that your advertising money will suddenly dry up, because the people who are funding you are also have a very close relationship to the government, right? And so there is a huge chunk of media that I think is not particularly enraptured with Modi, but they know which way their bread is buttered, and they’re not doing anything to speak out. And then there are people who are speaking out, and they are few and they’re very brave, and I have friends, who are investigative journalists who are extremely courageous, and keep writing.

I think when we look back on this time, they will be vindicated. Because they will have maintained the record of this time. But this is not a good time at all to be a journalist. I think physical danger that you have — journalists get threats — but I think the physical danger that you have in the capital city of Delhi is still limited, in the sense that you could still be picked up and arrested, but I think the chances of being harmed or killed or whatever — all the things that can happen to a journalist — that has not been happening in the city of Delhi. But once you leave the city of Delhi, outside of the capital, there are lots of attacks on journalists. You know, people who are working in small towns, people working in other regional cities — a bit away from the public eye. And actually, not even small towns.

In Bangalore, which is one of the largest cities in India, there was the attack on Gauri Lankesh, who was a journalist, who was openly against this government. And, one morning, two guys came and shot her, you know. And I think that was a very scary — I mean it was a very tragic event that happened, and it was also in a long line of assassinations that had taken place of prominent intellectuals — professors, activists — in that area. But this was the first person of that prominence who was a journalist. And that became, I think, a big rallying cry for journalists, because, when you kill a journalist, every journalist, understands that that’s a message that is being sent out to you, right? Yeah. It’s a scary time. I’m scared. Like, I would not write all kinds of things — I’m just not brave enough, you know? I have friends who do it, but I would not write all kinds of things, because I’m simply … scared.

CC: Do you think that this is attributable solely to the authoritarian nature of Modi? Or do you think that there is some sort of knock-on effect of the blatant disregard for press freedoms that Trump is constantly spouting himself?

KC: I think that — it’s like what you said about how if, that books were published because there are people to read them, right? So there has to be a public that is willing to go along with this, right? That is willing to believe that, this version of reality is more appealing to me than some other version of reality that the press is offering, right? So — and I think there is a — there is a public that is like that present right now.

But that said, I think that that public can be fickle, you know? I think part of it is that I think that public can be really fickle. You don’t know what’s going to happen. People are willing to suspend their kind of credulousness — and sort of just believe things that they would like to believe, as opposed to, inconvenient facts. But I think that’s not necessarily a permanent effect. And I’ll tell you why. I think that a lot of times what you find is that — and I think social media is a good forum for this — you find that new facts arise, and that resonate with lots of people, right, and then they spread, and then they open up a kind of a new kind of conversation about a new reality, right, where a lot of people say, oh yeah, this is actually true, this is — I relate to that, right. This is happening, around me, and nobody’s talking about it, right. And that spreads very fast. Just like the rhetoric and the ideology, spreads very fast.

All of that is happening at the same time. And I think that one of the things that’s very hard for people to swallow is that it’s nice to feel good about something when the bad effects don’t affect you. But once you are starting to feel negative effects from sort of the vortex of bull—, then you start to reassess, right? Like if you don’t have a job, or if you’re worried about your kid’s education, or if there are other kinds of things in your real life that are adversely affected, then you start to reassess like the value of living in a world where, information is just something that makes you feel good, you know?

I guess one of the reasons like it’s really hard for, say, mayors to become these kinds of purveyors of fantasy information is because a mayor is living much closer to ground reality.

CC: Right.

KC: They have to actually talk about real things, like the garbage getting picked up. Trump doesn’t have to talk about that. Modi doesn’t have to talk about that. He can just sell you a dream, you know?

CC: Yeah.

KC: — an ideology — just, hot air.

CC: Right.

KC: But at some point, everything catches up. At some point, you’re a leader. You have to deal with facts on the ground. And, I mean, if people’s real-life existence is such that things are difficult for them, and you don’t address those things, then I think, yeah. I think you can’t sustain the bull—.

CC: That’s a great, optimistic note to end on. (laughter) Thank you so much for joining me today, Kush.

Paw in print

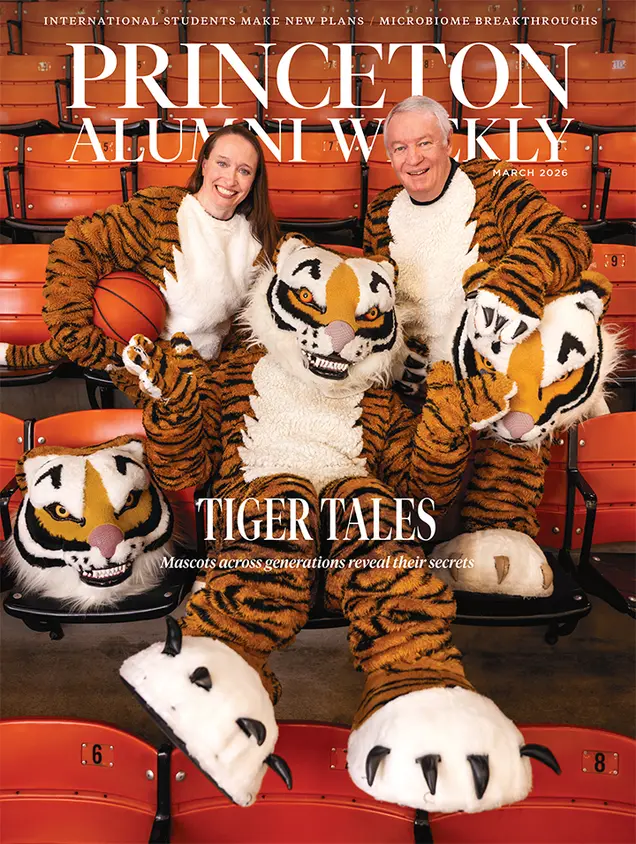

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

No responses yet