PAWcast: Lydia Denworth ’88 on Friendship’s Essential Role in Wellbeing

What the science of social bonds can teach us about our own relationships

The science is in and your friendships are not optional. Author and science writer Lydia Denworth ’88, author of the new book Friendship: The Evolution, Biology, and Extraordinary Power of Life’s Fundamental Bond, explains how until very recently, there was very little scientific examination given to interpersonal relationships. But today, new studies are increasingly showing that friendship was essential to our evolution as a species and remains a key factor in lifelong wellbeing.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: Hi, this is Carrie Compton and you’re listening to Princeton Alumni Weekly’s podcast. Today I’m speaking with science reporter Lydia Denworth ’88, who has just published a book called Friendship: The Evolution, Biology, and Extraordinary Power of Life's Fundamental Bond. The book explores the history of scientific research on friendship among humans and primates and just why our social bonds are so fulfilling, so necessary to our health and happiness. Lydia is a contributing editor for Scientific American and she has also authored two other books, one on the science of speaking and hearing, the other on the effects of lead on the human body. Lydia, thank you so much for joining me here today.

Lydia Denworth: It’s great to be here Carrie.

CC: So tell me: What did you find when you first started digging around into the field of friendship?

LD: So the really surprising part of this was kind of what got me interested in the first place, which is that there is this biology to friendship and an evolutionary story there for why we’re driven to connect with people even at the level of friends. And I think most of us, to the extent we think about it, we imagine that friendship is cultural, that it’s a product of human culture and language and things like that. And there is just so much more to it. And so this idea that friendship might be visible in your brain and in your genes and that there was a kind of wider story to tell just really struck me as interesting. And also I realized how seriously scientists were taking it and I thought that I would like to write a book that took friendship really seriously as well.

CC: So how did the scientific community come to discover that friendship was worth studying? Did it start with primates or did it start with humans?

LD: It started with humans. Although, actually right from the beginning you have both animal work and thinking about humans happening together, which is one of the critical pieces of this whole story. In my book, I locate the beginning with John Bowlby and attachment theory. So, Bowlby was a famous British psychiatrist who did this pioneering work on thinking about what it is that attaches mothers and babies and why babies sort of everything they do is designed to bond them more with their caregiver. Today, the idea that there should be attachment and love and affection between a mother and an infant seems really obvious to us, but when Bowlby proposed this back in the 1950s it was truly radical stuff.

Most Freudians at the time who kind of were dominating psychiatry thought that babies needed the food and shelter that their parents gave them and that that was the primary thing. And this idea, the reason it — I mean you say what does this have to do with friendship? Lots (laughs) because it was the beginning of understanding that relationships had a deeper purpose. And right from the start, Bowlby joined forces with a guy named Robert Hinde who was an ethologist at the University of Cambridge. Ethology was the beginning of studying animal behavior in the way that we sort of do today. And Hinde was interested in defining what relationships even were, like what did it — what was the definition of a relationship. And he’s studying animals so for him it was about repeated interaction and the sort of shared history that builds up with each time you interact with an individual. And Bowlby was looking for evolutionary explanations for attachment and he turned to Hinde who was studying animals. And so right from the start — and I love the fact that the new science of friendship sort of begins with a friendship — because these two became really good friends and they worked together for decades.

I really credit them with changing how we think about relationships and that really did ultimately lead to friendship. Because even Bowlby, everybody thinks of him as thinking about mothers and babies. But he thought that attachment applied all through life, and it applied to other relationships, not just parents and children.

CC: Right, right. And you also write in the book about how primatologists were very loath to assign the word friendship, that there was this sort of taboo about anthropomorphism in that community. Talk about that a little bit.

LD: There’s a famous paper called “Using the F-Word in Primatology.” And that paper is about contemplating whether it was appropriate. And this sort of dirty secret of primatology is that out on your field site when you’ve been watching the monkeys or the apes all day long and you come home and you’re sitting around and you’re having dinner together, they completely talk about friends. Or they’ll say so and so is just so nasty. Or they’ll use a stronger word. But in their academic presentations and papers they wouldn’t talk about friendship or any other concept that was too human. But the thing that has happened is that in this — in understanding the importance of these relationships, first of all they had to kind of define and measure friendship or social bonds. So, there’s all kinds of euphemisms in science, affiliative bonds, I’m forgetting now.

CC: Dyads and …

LD: Right, dyads and things like that. And they are ways of putting some sort of academic gloss on this connection, but actually it looks like friendship in many instances. And what happened in the primates is that that’s where the early definitions came. So studying animals allows you to kind of get rid of some of the complexity of human life where you’re trying to narrow down what does this really look like? And in the animals they were able to say these really strong bonds that we now call friendship in these animals, they are three things essentially. They’re long lasting, so there’s some stability. They’re positive. They seem to generate good feeling. I mean we can’t ask the monkeys how they feel about each other but they — you tend to do a lot of grooming with your closely bonded partners. And then they also have some reciprocity and some cooperation. And in humans that’s all still true really. I mean we also have other things. We have loyalty and trust and things that we hope that sort of add to the richness of our relationships, but at their core a quality friendship has those things. It’s long lasting, it’s positive, it makes you feel good, and it involves some cooperation and some back and forth. And that’s what — your friends are there to help you weather the stresses of day-to-day life. That’s truly what it’s about whether you’re on the savanna in Africa or whether you’re in Brooklyn where I live or here in Princeton, anything.

CC: So you write about how once we kind of get passed this mental block of talking about friendship and primates, somebody goes back and looks at large data sets of primate behavior. And what do they discover about the benefits to the primates of friendship?

LD: They discovered that the primates with the strongest social bonds who are the most socially integrated and the best sort of most — who spent the most time being nice to each other had the most reproductive success, which in baboons and monkeys means they had more and healthier babies who lived longer. And then they also had greater longevity meaning that the individuals themselves lived longer. And in evolutionary terms you really can’t do better than that. That’s what you’re after, reproductive success and longevity. And all of that work in primates was going on at the same time that people had begun to see in humans kind of in the same way, by following thousands of people over long periods of time and sort of measuring their health and also their social connectedness, that people saw that there was a link. But by getting it in both places in the humans and in the animals, the other animals we should say, you saw that there was a link. Then the question became but why? And let’s dig further into what it is that’s going on that would make a social relationship have an effect on how long you’re going to live in your life. And so that’s where all this science has centered is on trying to understand what’s going on in the body, under the skin. How can friendship get under the skin and change your immune system? And it turns out it does.

CC: How? Talk about that a little bit.

LD: In the immune system is just one example, but literally people who are more socially connected, and when I say that I don’t mean socially connected in a status way I mean socially connected, bonded, have close friends and good relationships. Those people are less susceptible to inflammation and viruses and things like that and vice versa. The lonelier you are the more susceptible you are to those things. And what’s actually happening is that in your immune system there are a variety of genes that control your immune responses. And how those genes get regulated, so whether they get turned on or off, essentially, depends on your level of social connection. And so it’s not something that you or I looking at the readout of the — if I took your blood sample and ran it through this — did a genomics analysis of it somebody who understands the immune system would be able to see how this set of genes is upregulated, which is the way they talk about genes that are turned on, and these are downregulated that are turned off. And it has this really fundamental effect.

The scientist who discovered that, he said to me he was so surprised. I mean, he’d kind of come along for the ride on this loneliness work and was looking at people’s blood samples. And he thought it’d be interesting but he didn’t expect to see anything like such a strong effect that was so clear. And he said, “Why would your leukocytes,” — your white blood cells — “care about that, about loneliness?” And what they’ve come to see is that it’s actually as — it has as strong an effect on the body and response to adversity that biologically we do as extreme poverty, child soldiers in Africa what they go through, all kinds of really dramatic things. And you say well really loneliness? This emotion that — but yes, it’s that bad for us. And then the flip side is that connection is that good for us.

CC: You also talk about what goes on in the brain when you are talking with a friend or you’re connecting with a friend or you’re making friends.

LD: We really have only just begun in the last decade or two to truly appreciate how social the brain is and how much social activity, I guess, is going on in the brain. But right from the beginning, human babies come into the world predisposed to be social but they need experience being social. And that is why seeing usually their mother’s face right away kind of primes the visual pump for things that look like faces. And then as you get into adolescence, there’s this kind of additional spurt of development in the brain so a whole bunch of new connections are forged and then pruned back again as you sort of get better. The way the brain really works is that it kind of throws a whole lot of stuff out there and makes a whole bunch of connections but then it only really uses — it keeps the ones it uses. So you get a kind of explosion of activity in very young children and then a pruning back.

And then now we know that you get a second explosion of activity in adolescence and then another pruning back. And that second explosion in adolescence or a lot of it has to do with emotion. And kids, teenagers — this won’t really surprise anybody who was one or has one or knows one, which is all of us — they’re more likely — they’re more prone to risk taking, they seem to really be — care a whole lot about their friends and their social lives. And that is actually by design. In evolutionary terms, they need to be experimenting and taking risks and pushing away from home and beginning to test the waters, and they need to do that with peers their own age. And so, it’s why having a friend in the room changes how a teenager behaves. But it can change it for good, not just for ill. Like, we always think of peer pressure as a bad thing and it can be. But the neuroscientists and the psychologists who are looking at this, they think more in terms of peer presence. It’s just the fact that having the peer there changes the kid. And it’s because the reward systems are sort of really primed for social interaction. We actually remember what happens to us in high school more intensely than we remember things that happen later. There’s more emotion attached and that’s because the emotional parts of our brain are kind of hyperactive, and the reasoning parts of our brain haven’t caught up yet. So there’s a kind of a gap, a developmental gap. And it makes perfect sense that intense friendships or heartbreak and the emotions that go with that. That’s why that’s what happens in adolescence.

CC: And what happens with friendship in old age?

LD: Well so as you move through, obviously once you’re an adult, your brain is more fully formed, although it is always still changing. We know this now, that our brains are plastic in some regards all through life. But so, at the end of life, friendship is critical. It’s more critical to peoples’ health than their marital relationships. That’s maybe not true in the middle of life, but it is true at the end, which is really good news because it means that if you lose your spouse or family members that friendships will sort of suffice, friendships will work and they’ll give you what you need in terms of closeness, assuming you’re doing them well in that you’re being a good friend. I feel that one of the really critical points that I came to see here is that friendship is a lifelong endeavor, and too often we, especially in the middle of life, you get so busy with work and family, kids, and whatever it is that you’ve got on your plate, that we just tend to let them fall by the wayside. Everything else feels more urgent and more important.

We think, “Well, when my kids are out of the house or I’ve retired I’ll have more time for that.” And we really shouldn’t wait. And that was a very strong message that I got from the epidemiologists and other people that I spoke to who said — one woman said that if you think about it like smoking and you smoke from 16 to 65 and then you quit at 65, it’s still better to quit than not but damage will have been done to your body. And she said and too often both individually and certainly as a society we’re not focused on this piece of life until kind of later and damage is done. You haven’t developed those muscles maybe. You haven’t built those long-lasting relationships or you haven’t worked to maintain them. And it’s better if you do. It just is. But if you are looking to kind of make new friends in adulthood and you’re having a hard time with that, one of the things that seems to work is going to look for some opportunity to — like a volunteer job if you’ve retired, where the cause or the thing that you’re working on is what will bring you together. Rather than putting yourselves in a room and saying let’s be friends and it’s all about that, you need some kind of common cause and then it’s much easier to develop the strong relationships around that. The critical thing is that you do have a kind of inner circle with some strong bonds in there.

The average person says they have about four people in their most inner circle, and maybe that’s half family and half friends. But the point is that those are the people that you really can rely on, that you feel really good about. And it doesn’t actually matter if they’re family or frien— or not, if they’re biological relatives or not. What matters is the quality of those bonds. The step change for health, is between zero and one friends. So as long as you’ve got one you’re on your way. Now it is also true that the more people in your life you have, the healthier you are in some ways because it turns out that diversity of social relationships, so that you have relationships with family —like with a spouse, with parents, with in-laws, with siblings, with coworkers, with neighbors, all those things. Those people are less susceptible to illness as well and it’s not purely from a kind of host resistance like you’ve got more bacteria floating around that you’re getting immune to. It seems to be psychological too. So quantity does matter but quality matters most. And it matters for men and for women. And it’s — I just — we all just really need to appreciate how important this is.

The only other thing I’ll say that comes up a lot when I say that is people say, “Well but I’m an introvert. And I really like to sit home and watch Netflix and eat Ben & Jerry’s or have pizza or whatever it is by myself.” That’s good. I actually like to do that too. But two things. One is we use the word solitude to describe the sort of joy of being alone. And then we use loneliness to describe the pain of being alone. But what loneliness really means for psychologists is the mismatch between how much social connection you want and how much you have. So your perception of your connection matters a lot. And if you really truly do enjoy being alone, then that’s okay as long as you still have that one friend. I’m not letting you off the hook of the one friend That’s important. I do feel that there are some people who sort of play the introvert card but actually do want more connection or really enjoy it when they go out and do it. But if you just make that effort, almost everybody’s happy. And it turns out there was this fascinating study in Chicago where they — total strangers commuting on the train and nobody thinks they want to talk to strangers on the train. But everybody who did have to as part of the study said that they had a better time when they got to their destination, they enjoyed it better. So it’s like we have this hesitation to interact sometimes but we almost always are glad that we did. And so we should recognize that.

CC: Yeah, one great avenue that your book explores is social media. I was really excited to see that you included that version of friendship. And you had some really surprising scientific facts around social media that I don’t think get reported on very often. Talk a little bit about that.

LD: No, in fact I was the first person to report on most of it last year in Scientific American. And I will say that when I was working on this book, everybody said, “Oh you’re writing a book about friendship. I can’t wait to see what you have to say about social media and how it’s — how terrible it is,” was just sort of the constant refrain. You know how it’s getting in the way of relationships and all this stuff. And I was kind of dreading this because it feels like such a quagmire and such a thing that people have such strong emotions about. And the science to the extent I understood it seemed really conflicting. One study says social media makes you lonely and another one says it makes you feel connected. And there was a he-said she-said kind of aspect to it. But what was really striking was that once I waded in and I started reading everything, I found that there really was a story emerging that was pretty clear. And I was fortunate that there was a raft of new research happening just as I was sort of finishing up the book. My editor wasn’t thrilled because we were rewriting that chapter right until the last possible second. But the new science says — this is the headline: Social media is just not as terrible for us as we have been led to believe including teenagers. And I’ll explain in a second more specifically, but I think that’s really important to understand that there’s this kind of hysteria that we tend to get into about technological innovation and social media is just the next iteration of that. There are different ways that people measure the effects of social media. And they usually talk about social media and wellbeing, but wellbeing is a bunch of different things. And if you pick it apart, relationships as one piece of wellbeing is the thing — is the place where social media actually has the most positive effect. It’s still not a big effect and the effects to the negative, like depression and anxiety, are even smaller. So, the effects are small, they kind of cancel each other out, but on balance the relationship piece is the best part. And most interesting to me is the idea and actually the fact that researchers are finding is that if people use social media as an extra channel with which to communicate with their good friends, it strengthens the bond.

CC: So there’s a lot of science that’s yet to be unspooled around friendship. Tell our listeners some fundamental truths, a few sentences that you can definitely assign to the definition and the benefits of friendship.

LD: Friendship is as important to your health as diet and exercise. That’s one way to think of it. It affects your stress responses, your cognitive health, your mental health, your immune system, your cardiovascular system, the quality of your sleep, I could go on. The rate at which your cells age literally is affected by your levels of social connection. So you need to pay attention. You need to plan your day accordingly. From an evolutionary point of view competition is what comes to mind. And competition is a thing, it matters. But cooperation turns out to be just as important, and so really there’s an element of survival of the friendliest here. The individuals in multiple species who were best able to kind of foster these strong, positive bonds with other individuals are the ones that did the best in evolutionary terms. And that tells us that there is this — such a more fundamental need to connect than what we often think. We think of friendship as pleasurable and valuable but not invaluable.

CC: Optional almost.

LD: Optional almost and some people would say frivolous probably. And I’m here to say no. No, no, no, no, no. (laughter) — it is essential. It’s part of the infrastructure of our lives and we need to treat it that way. But what I hope people will do with that is — at least what I’ve ended up doing now that I’ve spent all this time working on this — is that instead of feeling like I’m adding to your to-do list and saying now you have to go do this with your friend in addition to eating your vegetables and going for a run and all those things. I am hoping that people see that it should give them permission to hang out with your friends because you are doing something important for your health. And even if you’re just going to dinner and you’re chatting or you’re going to go for a walk or you’re going to go play football in the park with your friends or whatever it is. Those things are really good for you in a way we just haven’t appreciated fully.

CC: Lydia thank you so much for joining me today.

LD: Thank you for having me.

Paw in print

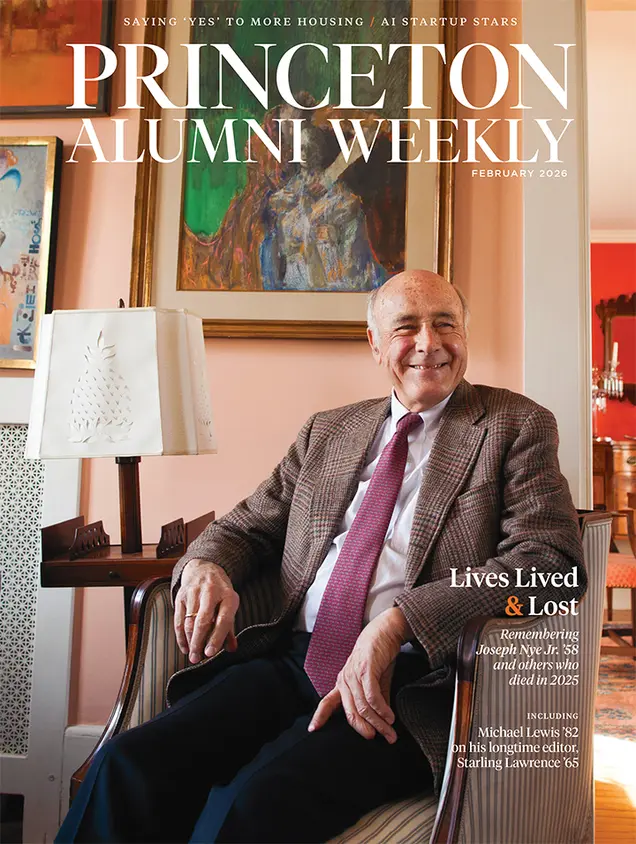

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

1 Response

John T. Mavros ’71

5 Years AgoPhenomenal PAWcast

Person-to-person communication and friendly relationships in technological society are terribly underestimated and sometimes even ignored. Having recently researched a book on improving the educational system, I loved and will employ the point that “friendship is as essential to your health as diet and exercise.”

The separation of parents and families from teachers and administrators is a critical part of the learning process that unconsciously was abandoned by forces concerned with desegregation of our schools in favor of focusing on the teacher-student relationship. In fact, the success of schooling rests on the balance of a three-legged stool that was always dependent on friendships and relationships that were established by the educational establishment with parents, families, and communities. The dissolution of after-school recreational activities for all (not “just” athletes), in loco parentis, corporal punishment (due to extremes of its implementation), and many other connections between schools and communities is evidence of how “friendship” was deprioritized and removed as an essential element in the field of education. Through dissemination of information Lydia Denworth ’88 and other researchers have to offer, I hope we will restore the importance of establishing communication and relationships by teachers with families.