PAWcast: Valedictorian Erik Medina ’25 on Changing the Chemistry of Plastics

‘In general, the advice I would give is there’s only 24 hours in the day and there’s a lot to do here,’ Medina said. ’Eventually, you’re going to need to prioritize what it is that’s important to you. There’s no wrong choice.’

On this episode of the PAWcast, we talk with Erik Medina, Princeton’s Class of 2025 valedictorian. Erik is from Miami, and at Princeton he had planned to be pre-med but after some soul-searching switched to chemistry. He focused his thesis on finding a way to safely upcycle PVC plastics — and had it published in an academic journal. Next year he’ll be teaching at his old high school, Ransom Everglades, and then he’ll head to the University of Wisconsin-Madison for a Ph.D. program in organic chemistry.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

I’m Liz Daugherty and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast, where we talk with Princetonians about what’s happening on campus and beyond.

Today I’m speaking with Erik Medina, Princeton’s valedictorian for the Class of 2025. He’s a chemistry major from Miami who reportedly loves organic chemistry and spent much of his time at Princeton researching ways to upcycle plastics. A news release from the University promised he’s found a way to turn my sushi takeout container into safe, useful chemicals. Erik has been accepted into a Ph.D. program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, but first he’s taking a year off to teach at his old high school near Miami.

So Erik, thank you so much for coming here today, and congratulations on being named valedictorian.

Erik Medina ’25: Thank you so much. I really appreciate it.

LD: Tell me about this research of yours. I really love the name of your thesis, “Burning Rubber Duckies with Flashlights,” which creates quite the visual. I understand it was published in a journal, which is pretty cool and also really unusual for an undergraduate. What were you looking into and what did you discover?

EM: Yeah. I think one thing, technically speaking, my thesis itself was not published. It was the work going into it, which was done in conjunction with a graduate student, Hanning Jiang, who was my grad mentor. But yeah, the project started off just building on previous work that was done by the lab in upcycling plastics using photothermal conversion. That is using light to generate heat. It’s a not entirely novel way, but a new approach to chemical reactivity that isn’t super widely used at the moment, in organic chemistry at least.

What we wanted to do was we wanted to find a way to access new chemical recycling strategies for PVC plastic. PVC is a really widely used polymer. It’s pretty ubiquitous in construction and personal applications, like packaging or the rubber duck, after which the thesis is named. But it’s not very recycled at the moment. The figures we often see are less than 1% recycling and nearly 1.9 billion pounds are land-filled, according to the U.S. EPA, per year. We wanted to look at new ways of accessing chemical recycling, making that waste material something useful. Not just from the scientific perspective, but also from, there’s an economic inefficiency in how much material is being wasted. There’s environmental concerns when it comes to plastic pollution and things like that. It was tying all those threads together.

LD: And it’s a safe process? It really creates something without creating any kind of toxic byproducts or anything?

EM: Essentially, what we wanted to look at was part of the problem with PVC recycling is that when you try to pyrolyze PVC, that’s essentially heating it to high temperatures under inner atmosphere, so without oxygen, you typically do that to plastics to try to crack them into fuel oils. That’s done to some extent with other polymers, but PVC tends to release HCL gas. That’s hydrochloric acid gas, which can be very corrosive to industrial machinery. If you try to co-burn it essentially with other plastics, you can generate some toxic byproducts.

What we really wanted to look at was, if this generation of HCL gas is unavoidable, if it’s going to happen anytime you heat this polymer, could we use it in a more productive way? Instead of just generating this byproduct. What we decided to do was build on the conventional strategies of using a base to absorb the acid. We thought to ourselves, “Can we use an organic molecule as a sorbent to quench that reactive HCL?” We turned to styrene, which is actually the monomer for polystyrene foam or mono-polystyrene plastic, because it’s so widely available. We found that we were able to, with pretty high efficiency and very good selectivity, convert that HCL and trap it with styrene to our upcycled small molecules, which we think would be useful industrially.

LD: Now, I can hear, as you’re talking right now, that you’re explaining this in a way that I can, not being a chemist, I can follow along a little bit. This is something else that the University had said about you is that you have an interest in pedagogy, right?

EM: Yeah.

LD: And in trying to help people understand science. You’ve done a bunch of things that they listed. You taught some middle school science for two summers. You’ve created some YouTube videos. Which I tried to follow. That was aimed at people that was doing some stuff that was a little more complex. Where does this interest in yours come from?

EM: I think it’s something that I’ve been interested in for a long time. I think that I was pretty involved in peer tutoring in high school, just going back, it was something that I was always very interested in. My mom’s an elementary school teacher. She teaches fourth grade, typically English. My dad’s a nurse and he taught for a while as a nursing instructor. I think I’ve always been interested and motivated in that direction.

LD: I thought maybe you might have had some teachers who inspired you?

EM: That definitely as well. I had an elementary school teacher, Miss Walsh-Crawford, Cleona, who was very impactful. She helped guide me into the middle and high school that I eventually attended. Also, here in the chemistry department, I’ve had some fantastic mentors. MTK, Michael Kelly *97. Eric Sorenson. Of course, my PI, Aaron. They’ve all been wonderful mentors, and they’ve also definitely shaped the way that I approach chemistry and that I approach a career in chemistry as well.

LD: I also suspected that you might have had really good teachers because organic chemistry is famously hated by students, right? Here, there, everywhere.

EM: I will say I think orgo here is actually extremely well-taught and I think generally the class receives very good reviews. I really do think that’s because of Eric Sorenson. I think he’s really a knock-out professor in the department and the University generally. I think if you read the course reviews every single one of them is, “Oh, this class is so hard, but he’s such a lovely professor.” I think he really sells the subject. He certainly sold me on it.

LD: Yeah? This is probably really hard to put into words because, what makes a great teacher? What does he do that makes it, you know what I mean? You know how teachers can do that?

EM: I think that he’s incredibly enthusiastic in a way that doesn’t come across as disingenuous. I think sometimes faculty are very good at their field, but I think that sometimes it’s hard to get that enthusiasm across when you’ve been doing something for 40, 50 years. It’s not always easy to get someone excited about it when they’re just getting their feet wet into it. Sometimes, I think that can come across as scripted or stilted. I think that he does a fantastic job of, just, he’s so passionate about it and it’s just infectious.

He tell us the same joke every semester about how, when he first learned about this one reaction, he fell back in his chair and he does this whole dramatic skit. It’s great.

LD: Oh, that’s cool. Now, you’re going to be teaching next year, at your old high school. How did that come about and what are you going to be doing?

EM: Yeah. I was always very engaged in my high school community and it’s something that’s very dear to me, that community. Then summer after freshmen and sophomore year of college, I was looking for things to do. I wasn’t really set on any path. I came into college premed, but didn’t really know what I was doing. I had seen this opportunity to work as a teaching assistant at Pine Knot campus, a half summer school, half summer camp thing at my old high school, teaching middle school science and algebra, and things like that. I jumped on that opportunity, I applied and I got the position. I did it, I really, really liked it. I came back the next year to do the same thing again, a little more in a leadership capacity working in a project-based learning lab class where I got to design different labs for the students in coordination with some of the other faculty. I really loved it, as well, as working as an undergrad course assistant here for organic. I think those experiences really just helped steer me in that direction.

LD: Did you like the light bulb moment? That’s what teachers always say is when you’re working with a student and the light bulb goes off and you can see that they get it.

EM: Yeah. I don’t know that I have a single light bulb moment. I think that I have a light bulb moment of, “Wow, I really enjoy doing this.” It’s very rewarding, as working in a preset, then getting to explain something to someone, and going back and forth with them, trying to lead them a little bit but not giving it away, and then they get it. You’re like, “Yeah, I did a good job, I got it.”

LD: Yeah, nice. Now, you have already been accepted into Wisconsin-Madison, so I guess you’re deferring for a year so that you can go teach.

EM: Yeah, I’m deferring for a year.

LD: What are you going to be doing there? It’s more organic chemistry again, I’m assuming. Do you have plans for research?

EM: I don’t know exactly what research direction I want to pursue. I definitely think that I want to build more into more “traditional” organic chemistry rather than polymer chemistry, which is more that I’ve been doing here. More like what would be considered organic methods. That is to say instead of trying to build a particular molecule, which we would consider synthesis, methods is more how can we make this specific linkage? Oh, we see that this linkage is very common in so many different kinds of important pharmaceuticals and important industrial agrochemicals, things like that. It’s how do we actually build that? It’s great if you’re a biologist and you’re looking at all these molecules for anti-cancer properties, but how do you actually build it? I think that’s where the organic chemists come in and that’s something that I’m very interested in doing.

LD: OK, cool. Then see where that takes you-

EM: Yeah, exactly.

LD: ... as you go through. Are you interested in being a professor and using this teaching some more?

EM: That’s a fantastic question. I don’t know. I’m hoping that the teaching experience will give me some clairvoyance as to what exactly I want to do post-grad, or at least post-grad school. I think at the moment, I really like the idea of being a professor at a PUI or something. Amherst, Davidson, those kinds of schools. I don’t know that I’m necessarily interested in doing R1 research, like running a big lab at a big university, but I think that smaller environment is something I’d definitely be interested in doing.

LD: Where you might have a little bit more work with students. That kind of thing?

EM: Less grant writing and things.

LD: I could totally see that. Now, on another subject, you’re really into languages. That was something else that jumped out at me. I’ve got here, tell me, you are bilingual in Spanish and English?

EM: Yeah, definitely fluent in Spanish and English. Then I also took French and Chinese for many years. And I took an ASL class here. I definitely would not say I’m anywhere near fluent on that, but that was a great experience.

LD: That’s five different languages. A lot of students hate their language requirements. What is it that appealed to you about the languages?

EM: I started taking a double language essentially for an elective in middle school, because I already spoke Spanish at home. I didn’t really want to just keep taking Spanish, I thought that’d be boring. In all honesty, I was trying to run away from my art requirement and they let you do a second language in place of that. I was like “yes, we’ll do that.” I took French and Chinese. I do not have the dexterity to do any sort of art or music.

I really loved it. I started taking Chinese. I had great professors in French and Chinese both throughout middle and high school. I think that by the end of high school especially, I had taken Chinese for many years and I still wasn’t quite at the spot that I really wanted to be, as far as having conversational ability or actually being able to use the language in a functional capacity. I could take an AP test and do well in it, but I didn’t initially have that spark to hold a conversation. I wanted to keep going with it. I decided to take the placement test and take the intermediate Chinese sequence here freshman year. That was great. The Chinese department here is lovely. I think in general, the language departments are great, but the Chinese department is really a standout as well.

LD: Oh, awesome. What about your Princeton experience, when you look back on, what are you going to say are maybe the best parts of your Princeton experience? And is there anything that you would change about Princeton?

EM: Yeah, that’s a great question. I think that standout experiences, there are certainly a couple academic ones. There were some classes that I really enjoyed taking. I really enjoyed the ASL class I took. It was something that I did not have on my radar. I took a dinosaurs class this semester, which I really loved; 10-year-old me was like “yes” in the back of his head. But really, I think it’s more the social experiences. Getting to meet a lot of amazing people, joining an eating club and doing all the classic Princeton things through that. That was really fun.

I think as far as things that I would change, this is very much a hindsight is 20/20 thing, but I came into college not knowing what I was doing, or thinking that I was doing one thing and I ended up totally pivoting to something else. I think that if I had known that I’d be more teaching, research, I would have maybe changed the way I took my courses a little bit, or done something like that. Different activities, maybe. I think I’d definitely tell younger me to chill out a little bit. I think I came in very much the premed “no, you need to go, it needs to be perfect.” I think that I’d definitely tell younger me “it’s going to be OK, just relax a little bit.”

LD: That’s a good segue into a question that I always like to ask the valedictorian, which is what advice would you give to incoming Princeton students who are now in the position that you were in four years go? They’re coming in the fall. What advice would you give them about what to do here?

EM: Yeah. It’s a great question. I think it’s difficult because everyone’s experience is going to necessarily be very different. It’s very hard for me to speak to the experience of someone who’s going to have a very different trajectory in a very different major, maybe doing a sport or something which I didn’t do.

I think in general, the advice I would give is there’s only 24 hours in the day and there’s a lot to do here. Eventually, you’re going to need to prioritize what it is that’s important to you. There’s no wrong choice in that aspect. Eventually you’re going to find something that’s important to you, whether that’s a team or a club that you’re involved in, whether that’s working really, really hard on your classes, doing research in a lab or in the library. Or something totally different. I think everyone has something that they’re really passionate about and you know what your priorities are, no one else does. Just make sure that you focus your time on your priorities, and then everything else will follow naturally. Don’t necessarily force yourself to fit a model, because it doesn’t exist. Everyone has their own thing to do.

LD: I think that that’s really, really good advice. You can’t do it all.

EM: Yeah, you definitely cannot.

LD: So know that going in. I think that’s really good advice. This gets through a lot of my questions. Is there anything else? Is there anything that you’d like to talk about or anything else you’d like to say?

EM: That’s a great question. I don’t know that I really have any words of wisdom. Maybe I’ll have some in the speech I deliver at Commencement, but at the moment I don’t know that I have any great pearls for you all.

LD: Did it take you by surprise when they named you valedictorian?

EM: Oh, a little bit, yeah. I think I mentioned this before, obviously I worked really hard in my classes. It’s not like, “Oh, my God, I can’t believe.” But I definitely was not expecting it. Look, it was not a goal of mine, I wasn’t working for that. It was more of, I guess hard work pays off sometimes, like validation. But it definitely was not a goal or something I was working towards.

LD: Yeah, I can understand that. Let me tease out one more thing from you really quickly.

EM: Sure.

LD: Because you mentioned you came in as premed?

EM: Yes.

LD: Then you changed your mind.

EM: I did.

LD: Tell me about that decision, because I think that this is another experience that Princeton students have. We keep hearing that the pressure to figure out what you want to do is getting earlier and earlier.

EM: Yeah, it is.

LD: To change paths like that, how did that go? How did that happen?

EM: I think it happened because ultimately, I just decided that I didn’t want to be a physician. It had very little to do with the actual field of medicine as a science, or an intellectual or academic pursuit. But really, I didn’t want to be a practicing physician for personal reasons of I didn’t think that, I’m someone, I’m very much a perfectionist and can be very anxious about their work. I think that the pressure of knowing that there’s people’s livelihoods at your responsibility was something that I wasn’t necessarily comfortable with. I know that going forward, I didn’t necessarily want to spend 30, 40, 50 years of my life doing that.

I think that there were other things I was just as excited about academically. I love medicine intellectually, but it wasn’t that path. Versus chemistry was something that I can engage very similar to that, a similar pathway, in a profession that I think lined up better with my personal values and interests moving forward.

LD: That was really smart to figure that out now than when you’re halfway through medical school, am I right?

EM: And cheaper.

LD: Exactly. I guess you got a lot of support. Did you get support from the faculty and from everybody?

EM: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah.

LD: Yeah, in helping to figure that out and make that happen. That’s fantastic. Very good. Well, thank you so, Erik, for doing this.

EM: Yeah. Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it.

LD: Yeah, absolutely. Good luck next year. Yeah, congratulations.

EM: Thank you so much.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

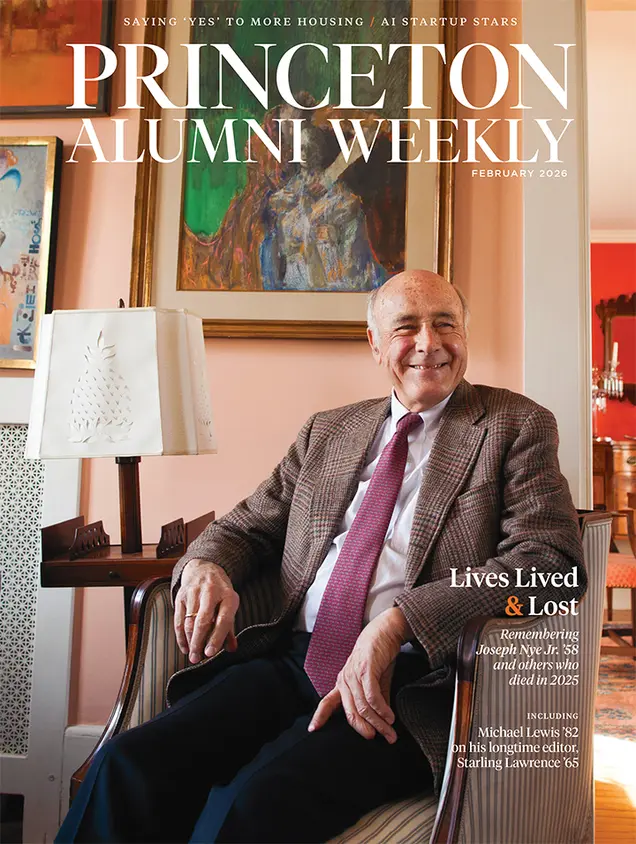

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet