The culture wars are fought by volunteer armies, but like Vladimir Putin and the old British navy, they sometimes grab unsuspecting conscripts and force them into battle against their will. Maitland Jones Jr. is trying to avoid being one of them.

Jones, an emeritus professor of chemistry at Princeton, was on the front page of The New York Times in October after New York University, where he has taught organic chemistry since 2007, notified him that it would not renew his contract. That decision came after a student petition last spring accused him of being too demanding in his expectations and too harsh in his grading. (Jones, in turn, filed a grievance against the university, which was summarily dismissed.) Since then, his inbox has been flooded with interview requests. He has granted a few — to The Chronicle of Higher Education and PAW, among others — but turned down many, including Dr. Phil and Fox News. Not that those outlets got the facts of the story wrong, Jones says, “but it seemed to me that there was danger of things moving in a direction I didn’t want.”

Though he resists becoming a political football, Jones has strong views about what happened to him. “Teachers must have the courage to assign low grades when students do poorly without fear of punishment,” he wrote in an Oct. 20 op-ed for The Boston Globe. It is easy to see why the story has become so controversial. Depending on one’s perspective, he is either an old-school defender of academic standards or a relic out of touch with modern pedagogy, his students either snowflakes or discerning consumers taking control of their own educations. Despite its catnip quality for culture warriors, Jones’ experience does highlight several controversial topics, including the status of adjunct faculty, the alleged dumbing down of higher education, and the changing power structure within the academy. It also raises some central questions, among them: Should students be expected to meet a professor’s standards or the reverse? And should grades represent whether students learned the material or how hard they tried?

Organic chemistry is a famously difficult course that nearly all premeds and chemistry majors take early in their academic careers. While Jones has always set high standards, he has also earned a reputation for seeking new ways to make the material engaging. He is the author of a popular textbook, now in its fifth edition, and is credited with introducing a new approach to teaching the subject that has students tackle problems in small groups rather than watch him diagram molecules on the board in large lectures.

Jones taught at Princeton for 43 years, becoming the David B. Jones Professor of Chemistry. “Colleagues have lauded him as the best science professor at Princeton, and one of the premier teachers in the country,” Samantha Miller ’95 wrote in a 1993 PAW cover story that labeled Jones the “Orgo Master.” “Several premeds have been heard to exclaim, ‘Jones is God!’” In a phone interview with PAW, David McCune ’87, now an oncologist practicing in Washington state, recalls that Jones’ organic chemistry class “was the first really demanding class many of us had ever taken.”

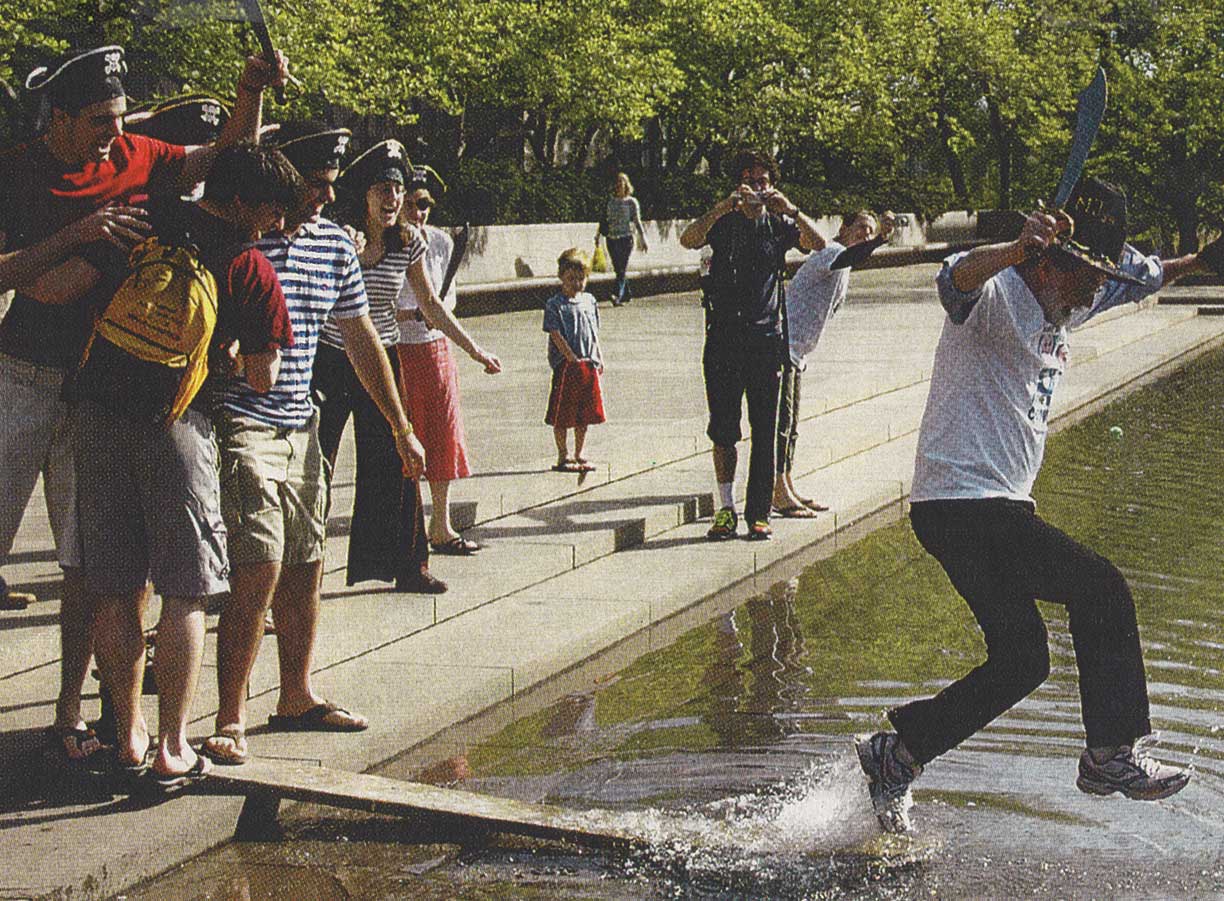

Jones, who was known for his sense of humor and casual demeanor, was widely beloved by his Princeton students. He was the recipient of several practical jokes, including more than one pie in the face, according to PAW. In 2007, a group of about 20 students dressed as pirates interrupted his final lecture and marched him over to the School of Public and International Affairs, where they made him “walk the plank” into the fountain. Jones is also a noted jazz aficionado and, in his younger years, ran with students in an informal group called the Hash House Harriers.

Concerned that large lectures might not be the most effective way to teach organic chemistry, Jones decided to try a different approach, breaking students into small groups and setting them to work solving discrete problems. He introduced it as a freshman seminar in 1995 and 1996, and it proved so successful that Jones scaled it up to his regular organic chemistry classes. Many other universities have since copied Jones’ model, says John Hartwig ’86, a chemistry professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Indeed, one of the reasons Jones began teaching at NYU following his retirement from Princeton, he says, was to prove that his small-group teaching approach worked outside the Ivy League. (He continued to offer a lecture-oriented section, as well.) From all indications, it did. In 2017, Jones was listed as one of NYU’s “coolest professors” by writer Nour Che on Oneclass.com. While acknowledging that Jones could be demanding, Che wrote, “[I]t’s really just tough love: Maitland will push you to understand organic chemistry radically and you will come out of his course having the best tools to use to become a chemist.”

Dissatisfaction with Jones’ classes seems to have coalesced several years ago. According to NYU, his student evaluations were the lowest of any undergraduate science course. In November 2020, during a year when NYU offered a hybrid of in-class and online instruction, students submitted a petition criticizing Jones for burdening them with an excessive workload, providing too little feedback, and showing a lack of empathy, particularly during COVID and a time of political unrest.

“I am so sick of mentally ill and financially disadvantaged and otherwise marginalized students being shoved out of pre-health and other fields because they don’t have the money and neurology and other privileges to make it through these unnecessarily difficult and frankly sadistic courses,” the petition read in part, adding later, “We shouldn’t have to cut back on working jobs, spending time with family/friends, and taking care of ourselves for this class.”

A second petition, signed by 82 of 350 students in the class, was submitted last spring. “We are very concerned about our scores and find that they are not an accurate reflection of the time and effort put into this class,” it read in part, adding that Jones was sometimes acerbic to those who performed poorly and “failed to make students’ learning and well-being a priority ... .” The petition did not, however, explicitly ask for Jones to be terminated.

Nevertheless, in August Jones received a note from NYU’s dean for science informing him that his contract would not be renewed because his performance “did not rise to the standards we require from our teaching faculty.” NYU also allowed Jones’ students who were dissatisfied with their grades to expunge them from their transcripts by withdrawing from the course retroactively. In a statement to The Times, a university spokesperson added that NYU was reviewing all its classes with high failure rates and asked, “Do these courses really need to be punitive in order to be rigorous?” Several of Jones’ colleagues in the chemistry department expressed their support for him in a letter to the NYU science dean, writing that his dismissal could “undermine faculty freedoms and … enfeeble proven pedagogic practices.”

Following the news of Jones’ termination, the NYU student paper approached several of his students, most of whom declined to comment for fear that it might hurt their medical school applications. One of them, however, told the paper that she had not availed herself of extra help because Jones “was not receptive to questions, and I didn’t want to open myself up for him to be rude to me.”

Jones, who turned 85 in November, says that students expected good grades in a rigorous course without putting in the effort necessary to earn them, even after he made some of his exams easier. Nor had they taken advantage of additional resources they had demanded, such as putting lectures online (which he recorded at his own expense) and offering additional office hours.

“They weren’t coming to class, that’s for sure, because I can count the house,” Jones told The Times. “They weren’t watching the videos, and they weren’t able to answer the questions.” Jones also noted that students were failing to read exam questions carefully, even when he tried to highlight potential traps, a problem that had been growing worse for nearly a decade. Exams that should have yielded a B average began yielding a C-minus average, and some students even earned zeros, something Jones says had never happened before.

In Jones’ estimation, it is student skills that have diminished, not their intelligence. “The students aren’t dumber [today]. They’re not.” He cites several possible explanations, including the amount of time students now spend on their phones and the loss of in-class instruction during the pandemic, but does not posit an answer except to say, “If I gave the exams that I gave 20 years ago, people would be more unhappy than they are.”

After The Times story appeared, several of Jones’ former Princeton students took to social media to defend him. Joanna Slusky ’01, an associate professor of molecular biosciences at the University of Kansas, tweeted, “Maitland seemed to really care about student learning, and he was absolutely at the leading edge of pedagogy.” Sanjay Patel ’91, a physician in western Pennsylvania, called Jones “an engaging teacher and a fair grader with clear expectations ... . Can’t believe NYU has done this!”

Although organic chemistry is often described as a “weed-out” course intended to deter students who are not capable of doing high-level work, Jones says he dislikes the term and disagrees with the sentiment behind it. “We have no intent to weed people out,” he told the Chronicle. Instead, speaking to PAW, he calls organic chemistry, “a learn-to-think class within the context of a new language.” And that, he believes, is important to anyone considering medical school, whether or not they actually use organic chemistry in daily practice.

“What we try to do is produce people who can look at a set of data on something that they haven’t seen before and draw logical conclusions, hypothesize about how you get from A to B,” he says. “That’s called diagnosing.” Furthermore, Jones believes, whenever the Nobel Prize is someday awarded to scientists who discover a cure for Alzheimer’s or some other disease, “I guarantee you that those winners will have had to think about that problem at a molecular level. That’s organic chemistry.”

Though Jones was already at the end of a long and distinguished teaching career, some have expressed concern that his dismissal illustrates the precarious professional status of adjunct faculty. In an interview with The Daily Princetonian, Jones defended his fellow adjuncts, saying, “If a person’s career exists at the peril of some disgruntled students writing to the deans, then he or she just can’t write real exams, can’t teach hard material — serious material.” The Academic Freedom Alliance, a group of college and university professors, also released a statement, saying, “NYU’s decision ... appears to be another example of the trend in higher education to devolve more academic authority from faculty into the hands of administrative entities whose backgrounds and expertise reside elsewhere than pedagogy, research, and the pursuit of truth.”

One of Jones’ teaching assistants, Zach Benslimane, suggested in an email to NYU officials that student complaints about Jones had less to do with his teaching methods and more to do with their low exam scores. Grade inflation has been a perennial concern in academia, including at Princeton, but it is the assertion in the NYU petition that student grades were “not an accurate reflection of the time and effort put into this class” that draws it to a fine point.

Flattening the grading curve causes several problems, Jones believes. For one, conflating accomplishment with effort demeans the work of those who excelled in the course. Indeed, following his dismissal, Jones apologized to his top students. “I didn’t stretch you,” he wrote in an email, “and thus deprived you of the chance to improve beyond an already formidable base.” Similarly, easy grading deprives less successful students of necessary, though painful, feedback. As essayist Freddie deBoer wrote in the online journal Persuasion, “I want to suggest that the students who launched the petition were denying themselves a central element of education: figuring out what you’re not good at.”

Ultimately, while effort should correspond to outcome, that is not always the case; certain material, including organic chemistry, comes easier to some people than to others. Jon Miller ’07, one of Jones’ former students, is now a recruiter for a pharmaceutical research company. From his vantage point, the purpose of grades in higher education is to indicate — to parents, graduate programs, potential employers, and the students themselves — whether they have mastered a particular body of knowledge.

So far as the outside world is concerned, Miller warns, “No one cares how much you tried. That’s for middle school.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

35 Responses

Gene Kopelson ’73, M.D.

3 Years AgoJones’ Orgo Predecessors

I was very fortunate to have known Professor Jones well. I had taken “Organic Chemistry” my sophomore year with the legendary masters of “Orgo,” the acknowledged toughest graders teaching this most difficult course at Princeton, Professors Paul Schleyer and Edward Taylor. Several students in my year, having studied extremely hard, managed to ace the course and were very proud of this accomplishment. Deciding to major in the brand new field of biochemistry, I chose Professor Jones as my senior thesis adviser.

But the next year, the organic chemistry course was turned over to Professor Jones. I had warned those of my friends who now would be taking Orgo how difficult the course had been. Working on my thesis in the lab that year closely with Professor Jones and his graduate students, I wondered how his Orgo students would fare. After both the midterms and finals, my friends said how easy Prof. Jones’ course was. I was shocked. Several then showed me their exam papers and grades — most with A’s and A+’s. Looking over the exam questions, indeed the exams seemed quite easy, compared to those of Schleyer and Taylor.

Working with Professor Jones, I had found him to be a most personable and warm teacher. So immediately, I went right into Jones’ office and chided him: How could he have given out such an easy final exam and so many easy grades? He just smiled. From then through my graduation, many times I teased him about him being such an easy grader.

After graduation and then into medical school and a career as a radiation oncologist, I kept in occasional contact with Professor Jones. He would send me follow-up bio-organic chemistry articles, which had extended the research I had done in his lab. I still appreciate his guidance as my thesis adviser.

So when I now read that NYU students complain of how hard a grader Professor Maitland Jones Jr. is, I think back to his easy exams and easy grades in the early 1970s. I laugh, wondering what today’s students would have said had they had to face Professors Schleyer or Taylor!

Harold Fernandez ’89, M.D.

3 Years AgoI Survived Jones. Here’s Why Others Can, Too

In the fall of 1986, as a sophomore student at Princeton University, I decided to enroll in organic chemistry. This course was so memorable that I wrote about it extensively in my memoir, Undocumented: My Journey to Princeton and Harvard and Life as a Heart Surgeon. Please let me share some of my thoughts on the course, and on the legendary professor, Dr. Maitland Jones, who recently was fired from NYU — making waves across American academia — because students complained that his course was too difficult.

For starters, the students at Princeton who were about to enroll in Dr. Jones’ course realized that it was going to be a challenge. As I recalled in my memoir: “There didn’t seem to be any other course at Princeton with the history, expectations, hovering anxiety and colorful lore of organic chemistry. Among students considering careers in medicine, this was probably Princeton’s most feared course. It was make or break for medicine.” When I was at Princeton, I was an undocumented first-generation student in America. I had nothing to lose, and I welcomed the challenge that was Dr. Jones with a refreshing rush of excitement and energy. I viewed it as an opportunity to do well, and to prove that I belonged.

But while we were aware of the challenges we would face during the semester, we approached Dr. Jones’ course with the fervor and vigor that a gladiator probably would feel before entering the Roman Colosseum. And, even more importantly, we looked forward to the privilege and honor of being under the instruction of a luminary in the field of chemical research. This is the Dr. Jones I knew and remembered: “The professor for this course was the legendary Dr. Maitland Jones, Jr., who in physique and personality oddly resembled Hollywood’s daringly adventurous professor, Indiana Jones. Slender and bearded, he had a discursive mind and published dozens of papers about many exotic and rare molecules. But he was also the kind of offbeat character who could be passionate about jazz and the Grateful Dead. He would make each lecture more animated than the previous one, and his enthusiasm for chemistry was contagious.”

Organic chemistry, in general, can be a dry subject. This was not the case in Dr. Jones’ classroom. As I once thought, and still do: “There were over two hundred students in his course, and it seemed that he hypnotized them all. Each morning, he lit up the board with rainbow-colored pictures of organic molecules interacting with their environment and with one another. All students had a special pen for this course that contained ink cartridges in several colors, so we could then imitate the same patterns that he used on his board drawings. When he changed chalks, you could hear, almost in unison, students clicking their pens to change the color of ink. By lecture’s end, the board looked like something dazzling and flamboyant out of Sesame Street. Dr. Jones was not there to teach students the basic chemical nomenclature, the equations, or the simple properties that govern the behavior of carbon-based compounds. That, he figured, students could learn by reading the textbook. And the fact that many of us wanted to go to medical school was the farthest thing from his mind. Indeed, many students gave up their dreams of pursuing medicine because they could not handle the intensity of his course. He was exploiting all his powers to show us esoteric aspects of organic chemistry, to show us the behavior of molecules we had not considered, molecules that needed to be imagined in three dimensions even if they had to be drawn on our two-dimensional notebooks.”

A professor who possesses the rare talent of making organic chemistry animated, interesting, and magical should not be punished because some students were not up to the challenge of meeting his expectations. Students at any university in the world would feel privileged and honored to learn from this legendary professor who has made learning organic chemistry an adventure for thousands. He should not be punished because some of the students feel so entitled that they cannot accept the idea of not doing well in a class. Organic chemistry in college is not supposed to be an easy feat. There are students who will not do well. There are even students who will fail the course, especially in more selective universities where some of the courses are taught at a faster pace and students are expected to cover vast amounts of material in short periods.

This man, and his life and work, should be celebrated in our society because of his lifelong dedication to research and teaching several generations of students who have made many contributions to medicine and science. We should be more open to taking on complex tasks and challenges and accept that not everything in our lives will come easy. We will all face many complexities in our lives, and we should be ready to find solutions. The solution for encountering a difficult course at a university is not to fire the professor, especially when he is a legendary American scholar. His reputation at Princeton was so high that at the end of the course, we would proudly wear T-shirts with the words, “I Survived Jones.” In my current practice as a heart surgeon, getting into the chests of my patients and fixing their hearts, I do not use the knowledge I learned in my organic chemistry course with Dr. Jones, but I am a better person, doctor, and surgeon because I learned many lessons of discipline, persistence and grit that were required to do well in his course. The NYU students are not any different from the Princeton students, but as a society, we are too eager to celebrate a mindset of entitlement that puts more emphasis on getting unmerited rewards, than on hard work, learning, exploration and accepting the concept that, sometimes we will fail, and that is fine.

Nabarun Dasgupta ’00

3 Years AgoRedemption After Failure

I was one of the organic chemistry students that Professor Maitland Jones failed. But I now run a public health chemistry lab and offer this tale of redemption.

In 1998, failing organic chemistry destroyed my hopes of becoming a doctor. A medical anthropology course revealed alternatives; a mentor steered me to public health. I went on to earn graduate degrees in epidemiology and am now on faculty at the University of North Carolina.

I disagree with Freddie deBoer that this type of course gives opportunity for “figuring out what you’re not good at.” The assertion dismisses the reality that sometimes we are called on to skill up on the very thing that we failed.

At UNC I specialize in preventing drug overdose. Since the COVID pandemic, overdose rates have soared as street drugs suddenly became adulterated with more than a hundred substances, each with unique clinical harm.

I suppressed my fear of organic chemistry and set up a laboratory to determine what is in street drugs, providing timely warnings and solving medical mysteries.

The day after The New York Times ran the story on Professor Jones, the same newspaper sent a photographer to take pictures of my chemistry lab. In December, The Times ran a full-page story spotlighting our work. It was then that I finally, and permanently, relegated the shame of failing. It took me 25 years to realize I wasn’t inherently bad at organic chemistry, but rather that I needed a real-world application to master the molecules.

Michael Sargent ’72, M.D.

3 Years AgoThe Poetry of Chemistry

As an English major, I found Maitland Jones’ organic chemistry course to be my most poetic academic experience outside of the English department. He emphasized understanding concepts and 3D visualization, instead of the rote regurgitation of desperately memorized trivia that characterized courses elsewhere.

I suspect that many students have found organic chemistry to be particularly stressful because they never wanted to be there, but were compelled because it was a critical pre-med requirement. Mr. Jones acknowledged that in his introductory lecture, stating that he would focus on teaching the minority of students who actually were interested in the subject. He added that there was no grading curve, and that everyone could get an A.

Imagine that: a course that rewarded mastery of the material instead of cutthroat competition in which a good grade was the primary objective. Your article questioned whether now professors are expected to meet the standards of students instead of the opposite. In Chaucer's time, this would have been considered “upsidoun,” a situation which could lead only to trouble.

E.J. Lightfoot ’78

3 Years AgoOn Standards and Fairness

This article presents a false choice between being fair to students and upholding standards. Upholding standards should not be optional, but being fair to students should not be optional either.

In my day, Maitland Jones’ organic chemistry courses sometimes were given the highest scores in student evaluations although Professor Toner’s Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics was usually first. Having taken both courses, the big difference I saw was that while both professors lectured well and had rigid grading systems (Toner using T-scores, Jones curveless absolute test scores), Toner projected a deep commitment to being fair to students and making the system fair. Jones, on the other hand, was openly callous about students and grading.

When I was disappointed with my final grade in “Orgo,” my TA explained that my penchant for using fountain pens left my exam books messy, so they were always left to the end and “people get harsher as the night goes on.” If that was true, it speaks to a lack of academic standards that is every bit as egregious as passing people who don’t deserve it. Even if it was just jive from a TA, it is emblematic of an attitude towards students that we accepted at the time as part of the cachet of a killer course to weed out pre-meds, but it appears the younger generation no longer accepts. Good on them! Standards may be timeless, but disrespect and capricious grading have no place in education.

David Fridovich-Keil ’15

3 Years AgoThe Role of Course Evaluations

I very much appreciated your recent article describing Professor Maitland Jones’ distinguished career and controversial dismissal from NYU. I would like to ask: Where does Princeton stand on questions of pedagogical freedom and student rights vis a vis coursework?

As a student, I always found course evaluations helpful in deciding which classes to take, and from whom. For example, I took “Differential Equations” from Professor Howard Stone in large part because the course had been positively reviewed; those reviews spoke highly of Professor Stone’s commitment to his students, his creativity in presenting topics, his fairness, and above all, the difficulty and the value of the material. Although there are many complicating factors, I worry that Professor Jones’ recent experience at NYU reflects what I have heard called a “customer service” mentality in higher education. I hope that Princeton does not fall victim.

Cameron Stout ’80

3 Years AgoCentral Questions?

The fact that these questions have become “central” and need to be asked says it all:

“It also raises some central questions, among them: Should students be expected to meet a professor’s standards [YES] or the reverse? [NO.] And should grades represent whether students learned the material [YES] or how hard they tried?” [NO.]

Andrew Lapetina ’07

3 Years AgoProductive Struggle

I appreciated PAW’s thorough analysis of the fate of Maitland Jones. While I never took his class, I would have benefited from trying. Nonetheless, I find discussion of his case ignores the deep connection between the failure of higher education to reach diverse audiences and the poor preparation and support for the actual teaching done by instructors.

In graduate school I taught an introductory engineering course and was provided no syllabus, standards, objectives, or guidance on what topics to cover. While this might be considered “academic freedom,” I likely did not appropriately prepare my students for more complex content they would encounter later, setting them up for failure.

We could charitably reframe the complaints of NYU students as a request for productive struggle. If serious, consistent effort in a course by qualified students yields no improvement, conditions may not be in place for a diverse set of learners to demonstrate mastery of that content. All alumni can recall a professor who had assessments that were not aligned to coursework, nonsensical essay assignments, or grades which emerged from thin air. These products of poor pedagogical systems leave many students, particularly first-generation college students, feeling confused, isolated, and frustrated.

The failure to prepare doctoral students in pedagogy, the lack of emphasis on teaching in the tenure review process at research universities, and the low emphasis on advising belies the academy’s beliefs about the ease of teaching. Most tragically, this keeps many talented students from seeing their efforts translate to understanding and excellence.

Cap Lesesne ’77, M.D.

3 Years AgoLasting Impact of Learning from Maitland Jones

I was a student of Maitland Jones at Princeton and am on faculty at NYU’s School of Medicine. The PAW article is a welcome and balanced addition to such a debate that is unfortunately raging through academia.

Maitland Jones was one of the finest professors that I ever had. He was rigorous and made us intellectually curious. Most of us scored near perfects on the MCAT exams because of him. Indeed, I would use what he taught me to obtain a U.K. medical license later in life. Those analytical processes and knowledge had not left me despite the passage of 25 years.

His comments about students not being dumber but less disciplined is true. NYU and the students made an error. Both will be poorer for it.

An acceptable accommodation would have been for the students to transfer to another class. That was probably rejected because a standardized test would have shown the superiority of Dr. Jones’ students who remained with him.

Alex Broadhead ’90

3 Years AgoWho Grades the Graders?

“The culture wars are fought by volunteer armies, but like Vladimir Putin and the old British navy, they sometimes grab unsuspecting conscripts and force them into battle against their will. Maitland Jones Jr. is trying to avoid being one of them.” Not an auspicious beginning; the culture wars are, by and large, fought by highly-paid mercenaries, not volunteers, though often enough their rhetorical arms target unsuspecting civilians — many of them teachers.

But that is not what I came to say.

The viral response to the story of Jones’ non-renewal by NYU brought up a multitude of old complaints from my academic experience (at two Ivy League institutions and a state school), the most salient in the form of questions: “What do grades mean?” and “How much effort should a single class require?”

I never took organic chemistry. But I did take a microcontrollers course that — like the one at Princeton — had a reputation for requiring 40 or more hours a week in lab. When I pointed out that it was possible to have more than one course with similar requirements in one’s schedule, and that, in any case, no one was taking only that course, the associate dean I was complaining too waved it off as “good preparation” for the engineering workplace. I’m sure Elon Musk would be proud.

What is accomplished by packing tremendous demands into a single course? (Are there [more] courses that should be split into multiple semesters?) While Jones denies that his course is a “weed-out,” organic chemistry notoriously is exactly that. If well-prepared students at elite universities, who are determined (I’ve TA’d many courses, but summer physics for pre-med students featured the absolute most determined students I’ve encountered!) to succeed, and willing to put in the effort, aren’t able to succeed, then I submit that there’s something wrong with the class or the teaching — not the students.

There was plenty of abysmal teaching while I was at Princeton: the Linear Algebra section that was so incomprehensible that they had to open a new section (taught by a grad student, who was actually the best teacher of the three) after the alternate professor’s section grew and grew in size; the Logic Design class taught by a new faculty member for whom English as not a first language, using the previous professor’s slides; the Differential Equations class that in which they decided to take attendance, and give in-class quizzes, after no one showed up to class the previous semester; the Intro to Physics professor who openly asserted that, “You can’t teach physics; you present the material and those that can, will.” But the one that seems to have brought me closest to the NYU orgo experience is probably the weed-out Electronics class in which the professor graded on a curve ... around a B- in a department that required a B average.

In order to facilitate his curve, the professor in question gave impossibly long exams, which did have the desired effect of stretching out the distribution of scores: the few people with previous familiarity with the subject material (or actual geniuses — they certainly exist at Princeton; or, I suppose, those who could devote all their energies to that one course — I was taking four others at the time) were way off to the right, then there was a pretty wide gulf, and then the rest of the normal distribution. Normally a good test taker, I panicked and got bogged down trying to solve a problem that I should have skipped, and was near the bottom on the midterm. I did better on the final, but only well enough for a C overall, and ended up in a different department. (It took a roundabout path and a few years to get my MSEE; I now work in tech.)

What is served by grading on curve in an elite institution? By forcing an artificially wide distribution onto a cohort of by-definition above average students? No one was even trying to evaluate our objective mastery-or-lack-thereof (to say nothing of our effort!) of the material — all the effort was put into relative ranking to weed out the “least fit.” I can’t honestly tell where Jones’ teaching and class fall — he sounds like he was at least once a pretty dedicated teacher — but I suspect that no one in the NYU administration was particularly surprised or bothered by low passing rates in Organic Chemisty, at least until the organized revolt. There’s been a practical mandate to use it as a pre-med gate and keep the supply of medical doctors low (and salaries high) since the mid-’80s, at least.

It’s disingenuous to decorrelate effort with success and then wring your hands about “lowered standards,” though that doesn’t seem to bother the myriad armchair “cultural warriors” for whom this is a call to arms. There are real, important questions about teaching, testing, grades, effort, and expectations (on all sides) here that deserve a much more significant examination than they’re getting in this he said/she said presentation — questions that aren’t new or popular or well-studied (or if they are well-studied, their solutions have not been widely adopted). It would be good if it didn’t take more serious crises with casualties on both sides for this to get more serious attention and study.

Ralph E . Duncan ’68, M.D.

3 Years AgoOrganic Chemistry Is Supposed to be Hard

Pre-med, including organic chemistry, is supposed to be hard! Of the 250 students in the Class of ’68 taking organic chemistry, only 95 pre-meds survived after the first semester. What’s the problem with that? As a practicing physician/surgeon I expect to work 24/7/365, work hard, always have the correct answer, and achieve 100 percent cure. Families do not want to hear, “I am sorry your loved one died; I did the best I could.”

Paul R. Hladon ’93, M.D.

3 Years AgoJones’ Rigor and High Standards

Heartfelt thanks to Mark Bernstein ’83 for his excellent PAW article about emeritus chemistry professor Maitland Jones Jr.

“We are here to teach you; we are not here to fail you” and “nodes are green” — two unforgettable quotes from Jones, replete with his massive sticks of colored chalk. Jones was easily one of our favorite professors at Princeton, and his exams were always tough, but always fair. Students could choose to answer or skip certain exam questions, provided that the total points added up to 100. The academic rigors — and rewards — of Jones’ legendary organic chemistry lectures were unequaled.

Now, fast-forward 30 years to the current climate on many university campuses. Should we shelter students from “unnecessarily difficult… sadistic [and] punitive courses” like organic chemistry? Should we simply reward students for their “time and effort,” and dismiss actual merit, skill, performance, and exactitude? Good luck trying to sell such axioms to pilots or doctors, or those who train them.

Please allow me one quote, from the heavy metal band Pantera (1992): “Is there no standard anymore?” Sadly, some students never got the memo. In the crucible, where they can be forged into something far greater, they must first be smelted, crushed, and hammered. But in many of today’s academic, business, or professional circles, young people seem to expect a perpetual, frictionless waterslide, followed by a soft landing in the swimming pool, where the water is always warm.

Professor Jones is a superb and gifted teacher, and we wish him Godspeed. Thank you for your service to all of us, Dr. Jones! You deserve gratitude, respect, and a pleasant retirement in the tropics, where snowflakes melt, and then evaporate.

Lyn Sedwick ’74, M.D.

3 Years AgoAppreciation From a Physician

I read with interest, chagrin, and then disgust the article in the December issue about Dr. Maitland Jones, who taught me organic chemistry — and I mean that, he taught me organic chemistry. I was someone, unlike many in my “orgo” class, who hadn’t already had experience with this discipline. In fact, I had to take inorganic chemistry first because frankly I had no chemistry at all in high school. Everyne knows “orgo” is the make-or-break class for pre-med students, which was my track, and the competition was fierce if not feral.

Dr. Jones made the subject interesting and understandable — so much so that the chemistry wonks did not do better than I did. And my exam first term got one of the highest grades. Why? Because of him. I had an “aha” moment that carbon atoms could combine in a circle to form benzene — I didn’t know that, but his teaching got me to that point on the exam.

I did graduate from medical school and have been a practicing neuro-ophthalmologist for many years. His course didn’t make me a good doctor, but it made me someone who understood that learning facts needs to be coupled with the ability to rework them, and sometimes quickly. This mental facility I see in most good doctors.

You cannot dumb down organic chemistry, in my opinion. I suspect the NYU students were expecting a good grade without putting in the work necessary to master the subject. Dr. Jones called them out and they apparently had the power to pull the rug out from under him. It’s a shame and totally unfair that he ended his career on this note.

Dr. Jones, I want you to know that you are my hero. It’s because of you, and the way you taught organic chemistry, that I became a physician.

Ted Georgian ’74

3 Years AgoOn the Limits of Student Evaluations

I first heard from a colleague of mine that New York University dismissed a faculty member for making tests too difficult; only later did I learn that it was Professor Maitland Jones, who tried to teach me organic chemistry in 1971-72. I didn’t learn all that much, and deserved the grades I got (C+, C-). It never occurred to me to blame him.

I had as a sophomore discovered that reading The New York Times over a third or fourth cup of coffee in the dining hall was much more pleasant than going to my first class of the morning, organic chemistry lecture. The course was taught with 19th century technology: blackboards that slid up to reveal another board underneath. I decided that if I got to class before the boards were all filled and the first erased, I could hurriedly copy everything (whatever it all meant) into my notes. Not a successful learning strategy!

Although I still cringe when anyone mentions organic chemistry, the experience didn’t ruin my life. I learned some things about being a student and went on to a career as a college professor.

The moral of this story is surely that college sophomores aren’t qualified to evaluate the level of rigor of their courses. Student evaluations provide a valuable source of information on whether professors come to class on time, end on time, attend their office hours, and other such mechanics, but couldn’t faculty in the department, a department head, or a dean have actually attended his lectures, evaluated the exams, and produced a professional evaluation?

Laura A. Janda ’79

3 Years AgoTreating Students With Respect

I was gratified to learn that Maitland Jones had been terminated from his post at NYU, and sorry only that it was not accomplished long before by Princeton University. Jones’ badass theatrics that so entertained his acolytes were too often laced with inappropriate callousness. The first (and last) time I dared to pose a question in his course, he mocked me with an exaggerated rendition of my “girlish” naivete, and then enjoined the entire auditorium (nearly all of whom were young men) to jeer at me. I remember this as an emblematic episode in the context of an atmosphere that was not particularly welcoming to women studying science at Princeton in the 1970s, and it still hurts almost 50 years later. I feel vindicated by Jones’ dismissal and pity the many other students he was allowed to torment decade after decade. All students deserve to be treated with respect. Period.

Loren Walensky ’90, M.D., Ph.D.

3 Years AgoThe Master Teacher of Organic Chemistry

I walked into the legendary lecture hall as a Princeton freshman and sat down in an orange upholstered auditorium seat among a sea of sophomore pre-medical students. In walked a slender man with a salt-and-pepper beard and a notable spring in his step. In one hand was a bucket of colored chalk and in the other a mug made of pottery. He filled a small teapot with water from the sink built into the laboratory bench at the front of the classroom, lit a Bunsen burner, and placed the teapot on a metal support that was perfectly centered above the flame. Once the tea was made, the professor — always with a spark in his eyes — reached into the bucket of chalk and the unforgettable magic of a Maitland Jones organic chemistry lecture began.

Each day that Maitland Jones lit a fire to brew his tea, he also ignited critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills in his pupils, challenging and inspiring generations of pre-medical students. He is singlehandedly responsible for putting me on the physician-scientist career path that I have been pursuing for three-and-a-half decades since, as a physician, scientist, and teacher. Whether organic chemistry is a “rite of passage” for becoming a doctor may be debatable, but the capacity to confront a formidable puzzle with the tools he provided, and then discover that you can independently solve it through a series of transformations to arrive at point Z from point A, represents the critical thought process — under time-pressure no less — that is essential both to succeeding in his class and to doctoring.

As chair of admissions for the Harvard/MIT MD-PhD program for 10 years, I have read thousands of medical school applications. A clunker grade in any one premedical course requirement has little to no effect on the outcome of a holistic review. In fact, the process of failing, learning from failure, persisting, and ultimately persevering represents the very grit and resilience that I seek in medical school applicants. Perhaps we should worry more about that “perfect” student who has never achieved anything less than an A, who will for the first time experience the inevitable failure that comes with pursuing discovery research or trying to cure an incurable patient. In those contexts, the formula of maximal effort in yields a guaranteed successful outcome simply does not apply. When the majority of experiments in the laboratory do not work, because after all you are seeking to find something brand new, critical thinking and creative problem-solving are the only means of moving from darkness to light. When you give everything you have got, blood-sweat-and-tears, to save a child’s life — such as in my profession as a pediatric oncologist — but your tireless efforts are ultimately not enough, you do not call it quits. You learn everything you can from that patient in the hopes of saving the next one.

Our American culture values, if not worships, the “greatests-of-all-time,” whether Serena Williams in tennis, Tom Brady in football, Muhammad Ali in boxing, Michael Jordan in basketball, or Simone Biles in gymnastics. Maitland Jones is, by every measure, the GOAT in teaching organic chemistry. If there was a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for teaching, he would be a clear winner. He has dedicated his life to it, nearly 60 years of teaching organic chemistry. Think about how remarkable that type of dedication is and the thousands upon thousands of students he has educated over those decades. Yes, he has high standards (thank goodness), and yes, organic chemistry is not for everyone. But a bad grade in his course can only preclude you from becoming a physician if you let it. Courses can be retaken to demonstrate mastery, whether during the regular school year or over the summer. I’m not sure I would want anyone taking care of me or my family who gives up that easily when confronted by adversity. Pursuing science and medicine is about leaving no stone unturned to uncover the answer to a profound scientific question or the antidote to an otherwise fatal disease. So, to Maitland Jones, I say thank you for setting such a high bar for your students, and shame on those who summarily fired you for being exacting. I, like countless others, will never forget you or your magnificent organic chemistry lessons, which changed our lives. Your legacy is felt by every patient we treat and every student we inspire.

Flash Sheridan k’51

3 Years AgoExcellent but Terrifying Article

An excellent but terrifying article; I am glad you had the courage to publish it. My wife has worked at NYU and is leaving academia for private research, and this makes me even more relieved. I was particularly struck by the petition’s assumption that mentally ill and otherwise marginalized students should not be shoved out of pre-health if they lack the necessary ability and prefer to spend time with family/friends rather than do the necessary studying.

Denn Dickey ’74

3 Years AgoEvaluating Students in Organic Chemistry

Maitland Jones was by far the best professor I had during my time at Princeton, and organic chemistry was my favorite class (despite graduating as an economic major). I am beyond bewildered that students at an accredited university would think that their grade should be a reflection of the time and energy required to learn the material rather than an evaluation of how well they understand the material.

Growing up, I could have spent all my waking (and sleeping) hours trying to develop my limited baseball skills, but never would I have made it as a professional, much less hit 62 American League home runs and been named MVP. Although, given the protesting students’ logic, perhaps I should be expecting a 9-year, $360 million offer from the Yankees any day now.

Rick Bond ’79

3 Years AgoRequired Reading for Every Parent

I’m certain that many of us have followed this situation with a wide range of perspective, perceptions, emotions, and even, perhaps, biases.

As a (belated!) parent of a high school freshman and a rising seventh grader, this article challenges me to think harder about what I want from our daughters’ education. As we head down the educational railroad that leads to God only knows what, multiple layers of complex inquiry emerge. How do we teach “resilience”? What is “learning”? What’s the difference between a “career” and a “vocation”? What kind of (and perhaps “which”) institutions are most aligned with our own personal expectations? How do we measure that success, and hold those institutions “accountable”? Learning “what we aren’t good at” is a lesson I learned with an early attitude adjustment at Princeton, with freshman physics and calculus (God knows they tried to help me). I also learn what I don’t know daily. Just ask my girls.

Personal position aside, I commend this thoughtful article for any parent, at any age, who has the luxury of having “choice” in the educational paths on which we place our children, or who has influence over the institutions — public and private -—to which we entrust that education, hoping for nothing more than success in life.

I may even challenge my ninth grader to read it. That’s a start.

Kelly Glostott ’95

3 Years AgoThe Orgo Matrix

Thank you for the thorough coverage of Maitland Jones’ adventure with NYU. As an orgo student in the early-mid ’90s, I’ve pondered why this exceptional professor faced such negative feedback. Perhaps his NYU students had adopted the habit of skipping over material they found too difficult, since next week’s topic would likely be a new chapter, and they could get by with some weak areas. I think this could work in most classes, and it’s an intelligent way to cope with a large workload. However, in organic chemistry, every class builds on the foundation of the previous one, continuing the structure for future classes.

Any neglected material would leave a gap that couldn’t be overlooked but would impair the student’s entire grasp of the subject. Once a student figured that out, they would likely be daunted by all the work to go back, comprehend that first difficult week, and then get caught up on all the following weeks; and they would just give up. Jones’ comparison of orgo to a language would support this idea: Suppose one week you just found verbs too hard and decided to let that week slide?

Robert W. Osborne ’96

3 Years AgoTeaching As a Two-Way Street

I began reading PAW’s article “A Combustible Mix” and fully expected to read about another professor being fired due to nonconformity with today’s campus woke ideology. Instead, what I read was music to my ears and a total validation of one of my life’s turning points from almost 30 years ago. I’m an engineer married to a physician, who often asks why I didn’t become a doctor, to which I usually grumble something about not being able to afford med school costs, etc. The real truth, though, is it’s because I took “Orgo” with Dr. Maitland Jones.

I was an “underprivileged” (poor) student working several jobs and playing multiple sports at Princeton in 1994, when I found his Orgo class to be just ridiculously difficult. As an engineer with two master’s degrees, I’ve always welcomed hard work and challenging course work, but Dr. Jones began each lecture with an assumptive air that he was speaking down to third year med students. I’m not shy either, so I’d ask questions, but as one NYU student said, you’d just be opening yourself up for a rude response with him. Freshman physics was tough, but they provided weekly review classes at night so you could keep up. I believe teaching is a two-way street, and I’d contend that Dr. Jones was absolutely guilty of not making sure that he was being understood and probably still has no idea of what it is like to walk a mile in the footsteps of some of his students.

It wasn’t just the C he gave me, but the complete feeling of ineptitude I was left with that made me forget about a medical career altogether. Meanwhile, my undeniably highly intelligent roommate, who didn’t have to worry about money, worked zero jobs, and played zero sports, got an A and later became the esteemed doctor that he is today. So at the end of the day, social standing does matter, and ideally you’d like to see professors who can teach classes that inspire, as well as inform, to students from all walks of life without crushing their souls.

Murphy Sewall ’64

3 Years AgoWhat Do Course Grades Mean Anyway?

I was a full-time tenure track (tenured in 1982) professor for 40 years at research one public universities. I puzzled over grading for nearly all of those years. The questions raised by the article are: “Should students be expected to meet a professor’s standards or the reverse? And should grades represent whether students learned the material or how hard they tried?”

Most of the classes I taught were required for departmental majors. Required in the sense that my colleagues who taught subsequent courses expected students competent in the content of the requisite courses. I submit that the answer to the article’s first basic question (including for organic chemistry — without question the most demanding course I took as an undergraduate) is: You bet students should be expected to meet the professor’s standards. Rare is the student who comprehends what they should learn as well as the experienced professor (whose standards likely are expected by colleagues, not simply his or her sole creation) does.

It’s mathematically impossible for everyone to be above average. Hence, roughly half of every class is filled by students who do less well than the majority of their peers. Those students commonly lament “but I worked really hard.” I learned in freshman physics that “work” is a measure of output (result), not how much energy (effort) was expended. Students usually do not like hearing that if there is a 1-ton weight in front of them and they struggle mightily to move it without success, they’ll be tired, but will not have accomplished any work.

If grades mean anything at all (and apart from everything else, they may not), then they must indicate that learning has taken place. Trying alone has no sustaining value.

As an undergraduate I assumed that the oft repeated “an C at Princeton is an A anywhere else” was simply hubris. However, my repeated experience after graduation was that statement is true more than not. In short, grading has no underlying scale. It simply isn’t realistic to compare grades from one institution to another and probably not from one department to another either (an A in physics means something different than an A in poetry). There have been a number of studies undertaken to understand what grades correlate with. I haven’t surveyed the field entirely, but my understanding is that grades predict only other grades.

For the last third of my career, the distribution of my grades tended to match the distribution of my colleagues. I explicitly told my students “In three years, no one will care what I thought (what grade I assigned), but they are likely to care whether you learned anything.” I did the best I could assigning grades that indicated the degree that students demonstrated mastery of the course material, but I suspect that the correlation was somewhat less than 1 to 1.

I do sympathize with students who are confronted with graduate school admissions that insist on high GPAs leading to a focus on competing for a relatively meaningless score card rather than on learning to think well and solve relevant problems. I think NYU made a serious misstep that undermines the institution’s integrity by attending to the wrong problem in the case of Professor Jones. His standards probably are the best measure available of the world his students will graduate into.

David L. Dresner ’78, M.D.

3 Years AgoDismissal Is NYU’s Loss

NYU’s controversial dismissal of Professor Jones is nothing less than an academic disgrace. I had the pleasure of knowing Mait Jones as the former master of Stevenson Hall as well as taking his “Orgo” course for two semesters and found him to be professional, personable, and always approachable. He had a unique teaching style which I found engaging and feel that his dismissal is truly NYU’s loss.

D. Bruce Merrifield Jr. ’72

3 Years AgoHis Joy and Integrity on the Squash and Tennis Courts

I took “Orgo” my sophomore year which was taught by Paul Schleyer, an excellent teacher. Schleyer left on a tour in the midst of second semester. A team of guest profs filled in for the balance of the year, one being Dr. Jones. Wow, who was this guy?

My junior year, as a starter on the varsity squash team, I somehow got connected to give Mait an afterwork squash hit. We had a great go, and he was a most gracious and enjoyable — victor! I later learned that he was equally talented on the tennis courts. It’s not often that you find such an all-around, capable, high-energy, and motivating person. What a gift to Princeton for so many years.

I had mixed feelings about the NY Times story. First, I was pleased to find that Mait had not retired at 65 to 70 but continued to serve the world with his great teaching and book publishing. But, I was distressed about his dismissal and the eroding student standards for hard sciences. When wokeness and statistical representation allow people to be chemists, doctors, engineers, architects, etc., with gaps in their capabilities, won’t subsequent accidents follow? And, who likes being in a position in which they don’t feel 110% masterful?

I know this opinion will inflame the hard-core representation/quota crowd. If so, I’m sorry. But I will ask for what other educational track/scenarios should exist? To pretend, more personally, that all kids who enter first grade — based on being 7 years old — should be able to learn at the same speed is wrong. Some will be overwhelmed and others quite bored. If you have a “privileged” ADHD, dyslexic kid in elementary school, should we pretend that your kid should be able to do a standard level of learning mastery? All kids are great! Shouldn’t they be educated at their respective speed to achieve full mastery? And, if some take a few more gap years before or during college, so be it.

Fast-forward, a diverse class is admitted to college averaging 18-19 years old. Why should we assume that they are equally able and equipped to take any course and do well? Should we just pretend that they all master every course and give them A’s and move them on? For hard math and science courses should we just dumb them down so everyone can pass? Or, should we — in some cases like Orgo — allow students to self-select into slow, medium, and fast-paced options?

Some students have always figured out their own workarounds. I had pre-med classmates who spent entire summer vacations just doing Orgo summer school (9-to-5, Monday through Friday) at hometown colleges to get it out of the way with a higher grade — all to get into more, better med schools. In the past decade, I have coached a few young men to take several gap years to work while acing one course per semester at a local community college to then transfer in as a sophomore into a bigger-time college and graduate at 25. Pretending that all kids are equally able to master tough courses and giving them fake grades for enrolling isn’t the answer.

Perhaps the positives that will come out of this negative NYU story will be new pathways to excellence in tough, hard courses for all students.

James R. Schueler ’66

3 Years AgoDesign Course Schedule Around Students’ Aptitudes for Happier Schooling

Students are probably more successful in school if they study what they are good at and what they are interested in. I recommend aptitude testing and an interest inventory prior to registering for a course of study. It doesn’t mean a student must register for organic chemistry if the aptitudes perfectly match those of doctors, but at least the student’s probability of success in school and in work will be greater. The Counseling Center at Princeton helped me to decide on a major by administering 40 hours of testing (do they still do that kind of thing?). I doubt I would have graduated had I not followed their recommendations.

Robert Taub ’77

3 Years AgoLearning How To Think

Having just read the article about Maitland Jones (“A Combustible Mix,” December issue), I heartily agree with the conclusion espoused by Jon Miller ’07. Professor Jones’ “Organic Chemistry” course was undoubtedly in the class of the most outstanding courses in my undergraduate experience. The intellectual rigor and unceasing commitment to excellence espoused by Jones embodied the essence of a liberal arts education — that is, learning how to think. Although I followed a nonmedical career path (music), that course was absolutely worthwhile, and truly inspirational.

Amy Hairston Crockett ’96, M.D.

3 Years AgoOn Dropping Organic Chemistry and Not Giving Up

Even considering the challenges and heartaches with the practice of medicine in 2022, I love working as a physician. I finished training 15 years ago, so I am solidly mid-career. By all objective measures, I have already had a very successful career in academic medicine and I’m still excited to do this work every day.

And so, from this vantage point of privilege and success, I had some complex emotions reading the article in The New York Times about Dr. Maitland Jones as well as the follow-up in the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

In fall 1993, I took organic chemistry from Dr. Maitland Jones. As others have noted, this was a notorious weed-out course for premedical students. I knew it would be tough and I worked hard.

Despite my effort, I failed the first midterm. I sat for three hours and managed to score just 23 points. A classmate scored in the single digits. “The average hovered around 30 percent” just like in the NYT article about the current-day NYU undergraduates in 2022. I dropped the class. So did she. So did a lot of other students.

I was 19 and knew I wanted to be a doctor someday. It still felt like a fragile dream, far away and in the future. The very real chance of failing organic chemistry was too much to risk.

I took organic chemistry again over the summer back at home at a local college. I earned an A-. And here I am, 30 years later, with a career I adore and an important legacy of service to patients, my community, and my students.

But many of my classmates never took organic chemistry again. They switched majors and changed career paths. I know they found success in many ways, but what about medicine? The field is not better off because bright young minds were discouraged by a professor like Dr. Jones.

It’s shocking from my perspective now. I remember how ashamed I was and how terrible it felt to fail. How many students abandoned careers in medicine as a direct result of Dr. Jones’ classes over those 30 years since I sat in his class? Likely hundreds. What a terrible tragedy.

I am a professor myself these days. I don’t want my students to “fear for their futures” like they did in Dr. Jones’ class at NYU in 2022 and I did at Princeton in 1993. That’s not “rigorous instruction” and it’s not necessary.

I would challenge those of us serving on medical school admission committees to consider applications holistically; applicants are so more than their organic chemistry grades. It’s up to us to identify and prioritize the unique strengths and skill sets applicants bring to the field of medicine. We should not be delegating this to undergraduate professors of organic chemistry.

As we recruit the next generation into medicine, how do we value not only academic achievement but also communication skills, empathy, integrity, leadership, and enthusiasm? How do we value diversity and distance traveled?

I also have a message for the students who are struggling: Don’t give up. Come join us in medicine. Don’t let bad experiences in organic chemistry keep you away from this field. We need you. It’s worth it. There is a place for you here.

Martin Schell ’74

2 Years AgoOrganic Chemistry and the Customer Mindset

I strongly recommend that Dr. Crockett read the Dec. 9 letter posted at PAW online by Dr. Loren Walensky, who is on a medical school admissions committee (chair of Harvard/MIT M.D.-Ph.D. program admissions) and says they do consider applications holistically.

I salute Dr. Crockett’s persistence in studying Organic Chemistry during the summer, a path that quite a few premeds have taken according to the online letter by Bruce Merrifield ’72.

However, her personal idealism and drive to become a doctor seem somewhat narrow-minded, almost as if it’s the highest calling for every human being. I recommend reading the online letter by Nabarun Dasgupta ’00, who failed Jones's course but reoriented and became an epidemiologist instead of a doctor — and now runs a chemistry lab at UNC.

My classmate Dr. Lyn Sedwick notes in her online letter: “His course didn’t make me a good doctor, but it made me someone who understood that learning facts needs to be coupled with the ability to rework them, and sometimes quickly. This mental facility I see in most good doctors.”

I think that is the point that most people are missing in their cries about fairness and effort. The point isn’t whether Organic Chemistry is essential to becoming a practicing physician; the point is that it trains one’s mind. The NYU misadventure is just more evidence of “customer” mindset: “I paid (or at least got a scholarship) to study at a selective university so I am entitled to the degree.” The purpose of a selective university is to develop your mind with better guidance than at other colleges. Denying the value of its challenge reminds me of the maxim, “You can’t have your cake and eat it, too.”

Anthony J. Cascardi ’75

3 Years AgoBravo!

Bravo, Maitland Jones! As a humanities major and now after a long career as a UC Berkeley literature professor and dean of arts and humanities, I look back with awe and admiration, and considerable humility, at my experience in Maitland Jones’ organic chemistry class at Princeton. I would have been less rewarded had it been easier, in spite of the fact that I was awarded the lowest grade of my undergraduate career in it. Again, I say: Bravo, Maitland Jones!

Justin Tortolani ’92, M.D.

3 Years AgoKicked in the Teeth by Orgo

I took Professor Jones’ “Orgo” in the academic year 1989-90, and in my view it was my first true college course, since much of my first year was a review in many respects of high school courses such as basic chemistry, writing, foreign language, and math. I remember being intimidated before starting the course and, somewhat embarrassingly, started reading the textbook in the summer before the class started. This turned out to be a ridiculous waste of time but it did assuage some of my anxiety. I remember being completely enthralled by the class. Whether it was how it made me think, or the cool visuals and seeming ease of Professor Jones’ ability to draw electron orbitals of various shapes and colors, or just the zeal and energy that he brought to the class, I was highly motivated to learn this new subject. I was also motivated by my fellow students, some of whom wanted to major in organic chemistry, as well as my dream to attend medical school. The concept of learning how we know things rather than just memorizing was also novel. Unfortunately, all of this excitement and energy came crashing down after my first exam result was a 33 (yes, out of 100). I remember calling home and telling my parents that I will need to set some new dreams and drop the class. My parents urged me not to. After my second exam grade came back with a 66 (yes, out of 100 again), I was pissed at my parents and myself for not dropping the class and now it was too late. I went to Dr. Jones for extra help, and things started to click. The rest of that the semester and the next were some of the most memorable and rewarding academic times of my life as I gained confidence in learning how to think deeply and solve problems.

As a parent, a spouse, and spinal surgeon, I am faced with problems every day that force me to think deeply and solve for unknowns. I have shared this story repeatedly with my children to emphasize the importance of learning over grades and that what you think is a horrible performance may not be that bad when compared to the whole. This class forced me to get way out of my comfort zone as a student, it forced me to think differently about my priorities, and made me think much more carefully about how I budgeted my time in college. It would have been much easier and a massive mistake to have dropped the class and taken it at a local college as many of my friends did. I am truly grateful for the 10 months learning “Orgo” from Dr. Jones, and although I still get a little nauseous when I walk by Frick, never in my wildest imagination would I ever have thought to sign a petition because the class was too hard. In life, we all get kicked in the teeth some day. It is how we react that makes the difference. Thank you Dr. Jones.

Karen Smith ’83, M.D.

3 Years AgoIn Defense of Maitland Jones

I took “Organic Chemistry” with Maitland Jones in 1981. I got a C. My average in my major of classics was an A. I applied to 22 medical schools, got interviewed at 11, and got into 6. Needless to say, everyone said, “Wow you are smart if you got a C in his class” and “He is really famous.” Yes, a rare few people did get A’s. He did not believe in curves.

I learned humility from my C in 1981. As a physician for 28 years, I know there is always a doctor smarter than me. If I need to consult Mayo or Baylor-MD Anderson, I call them. I am not the be-all and end-all of medical knowledge. Anyone who ever had his class would have learned good science is hard and you do not always get an A. There is no curve in trying to save people’s lives. You need humility to consult someone who may just be smarter than you. His class was disproportionately hard, but med schools knew a C from Maitland Jones was an A+ from someone else.

At the rate things are going, we would have fired Einstein!

I think he saved a lot of lives by knocking back premed egos just enough so that MDs learned to ask for help.

Martin Schell ’74

2 Years AgoOn Required Courses

Great letter, Dr. Smith. Reading the whole set online makes me see that something is missing from the pros and cons, however. Even those who grumble about his personality admit that Professor Jones loved his subject and taught it with enthusiasm.

So was it a drag to have the majority of his students start the course out of obligation? I’ve taught required courses and noticed that enthusiasm is often less than optimal compared to electives.

Most upper division courses at Princeton are (still?) taken by students majoring in that department, but I’d wager that Organic Chemistry had a majority of “I’m only here because I have to be. It’s a requirement for medical school. I’m not a chemistry major.”

Murphy Sewall ’64

3 Years AgoProfessor Jones Holds the High Ground

I taught marketing at a research I university for 35 years, retiring in 2013. I do not have the impression that students’ performance varied much during my career, but average grades did inflate. To the best of my knowledge, based on available research that I’ve read, grades do not predict much other than subsequent grades. That is, students with high grade averages as undergraduates will likely receive high grades in graduate courses. But, grades are poor predictors of career success measured by economic or alternative criteria.

By the end of my career, students tended to see even an A- as pejorative. After resisting for several years, I decided to follow the grading patterns of my colleagues. I did tell students that in a year or two, no one would care what I thought (what the grade was), but whether the students had learned the material would matter.

Students have a difficult time grasping the concept that work is a measure of output, or accomplishment, not energy expended. Only an ability to demonstrate a capacity to make sense of the subject matter counts. Organic chemistry was, by far, the most difficult course that I took at Princeton. I didn’t blame the professor or feel that somehow it should not have been more difficult than other courses. Some of life’s tasks are just harder than others. As President Truman said, “If you can’t stand the heat, stay out of the kitchen.”

When I was an undergraduate, I believed that the idea that “a C at Princeton was a good as an A everywhere else” probably was hubris. After graduation when I found myself in direct competition with peers who went to school elsewhere, I discovered that the notion about Princeton’s grades was more true than not.

Somehow, graduate schools, employers, and others who find themselves comparing candidates from different undergraduate programs must implicitly, if not explicitly, adjust for institutional differences in underlying measurement standards. Don’t college admissions staff face the same problem comparing applicants from different high schools? Is it the case that Professor Jones’ difficulty at NYU follows from the possibility that Princeton’s conversion of performance to grades is on a substantially different measurement scale than NYU’s? If Princeton grading standards are applied to a single NYU course, wouldn’t that distort the interpretation of an NYU transcript?

Armond Thomas Perretta *74

3 Years AgoAn Outstanding Teacher and Scholar

Mait was on the faculty during my graduate school years in Frick (the old one, for you youngsters). I was not interested in organic chemistry, but it was impossible not to know Mait, impossible not to know about him, or impossible not to have an opinion on the subject of Mait.

My considered view at the time was that aside from his addiction to The Preppy Handbook and khaki trousers, he was an outstanding scholar, a very fine teacher and mentor, a consummate researcher and research group leader, and ... er ... kinda cute in a New England sort of way.

The entire incident at NYU does little to bolster the NYU brand or to encourage observers to take the school seriously in the educational landscape. This does indeed come as news to me because I’ve always held NYU in high regard. No longer.

Good on ya, mate (or is it Mait?).

Norman Ravitch *62

3 Years AgoFaculty, Good and Bad

Every college or university has good and bad faculty, and in almost every field. What really counts is the accomplishments or shortcomings of those who get degrees, both undergrad and grad, from these schools. This cannot be assessed in a short time span and should be left to the future. NYU, in my view, has never been a university of high quality, even if many are happy there on the faculty because they want to life in New York City. Many students choose NYU for reasons that also have little to do with quality and much to do with the environment.