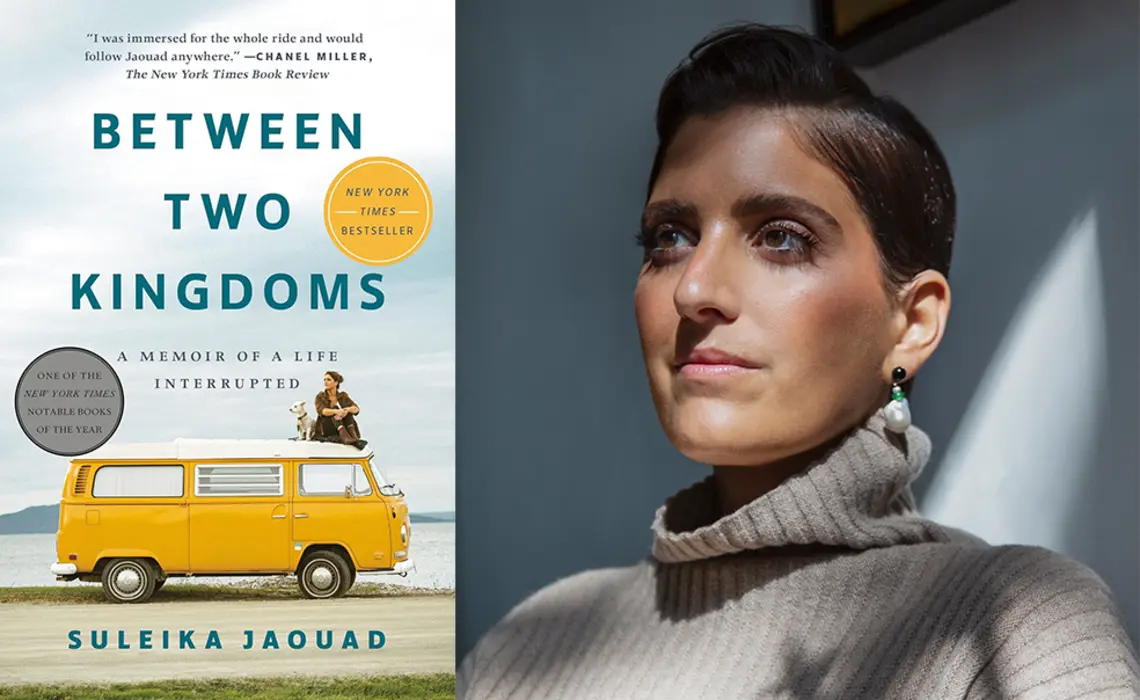

Suleika Jaouad ’10 Navigates Illness and Life by Pen

‘There’s a kind of power when you dare to inhabit the first person with unvarnished vulnerability and honesty’

Suleika Jaouad ’10 was barely out of Princeton when she was diagnosed with a rare, aggressive form of leukemia. The next four years were a whirl of hospitals and illness, and when she was finally better, she realized she needed a new sense of self. The memoir she wrote about both journeys, Between Two Kingdoms, is the kind that can help anyone struggling to find their way. On this episode of the PAW Book Club podcast, Suleika answered book club members’ questions about writing this deeply personal memoir and how she has sparked interest in creativity and journaling across the country with the publication of second book, The Book of Alchemy.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

I’m Liz Daugherty, and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s book club podcast where Princeton alumni and friends read a book together.

Today I’m speaking with Suleika Jaouad, from Princeton’s Class of 2010, about Between Two Kingdoms, her memoir of fighting a rare and aggressive form of leukemia and, afterward, finding a way to rebuild her life and her very sense of self.

In a way, the book began as a New York Times column about being a young adult with cancer, but it also evolved from Suleika’s practice of journaling. As for where it went, well, let’s just say that, when you’re struggling with something, this is the kind of book that can light the way. Just last year, Suleika returned to bookshelves with a follow-up called The Book of Alchemy, in which she explains what journaling has done for her and provides a bumper crop of inspiration to get anyone started on a journal themselves. She writes that while working on Between Two Kingdoms, she made this discovery: “If you’re in conversation with the self, you can be in conversation with the world.”

LD: Suleika, thank you so much for taking the time for this and for being a part of our book club.

SJ: Thank you. I’m so excited to be back, if not geographically at Princeton, at least mentally and through the airwaves.

LD: Awesome. All right, so my first question comes from Rachel Marek, who’s an undergrad alum from the Class of 2017, and she writes, “I wanted to say thank you for writing this book. As a fellow cancer survivor, this book meant the world to me when I read it. It finally made me feel seen, especially with the descriptions of some of your initial symptoms and feelings and also your feelings post-treatment. My question for you is, what were your favorite parts of writing this book?”

SJ: Thank you for those kind words, and thank you for that question. I have wanted to be a writer from the time I was old enough to hold a pen. The dream was always to write a book someday. To get to write this book was an immense privilege and it was also somewhat terrifying. Anyone who has opened a blank document and typed in the words Chapter 1 and then stared at the blinking cursor has likely some sense of what that was like.

But the surprise of writing this book was to shift to long form, to have the gift of time and space, to take the central questions of this book for a long walk, and to return to what you opened with this notion of being in conversation with the self as a way of being in conversation with the world. It was something I don’t think I fully understood until I embarked on writing Between Two Kingdoms. Even on the days when the writing wasn’t going well, to get to live in the world of this book, to get to live in the world of the characters who inhabit the book felt like a kind of teleportation that felt akin to magic.

I think, to answer your question more specifically, I got to write about friends of mine I met when I was sick in my early 20s, many of whom are no longer alive. To get to be in their company, to write those scenes, to revisit them and conjure them in ink was an unexpected joy. I expected it to be hard. I expected it to be painful. What I didn’t expect was to get to experience the delight of those friendships, the depth of those conversations, to laugh out loud at the humorous moments we shared. And one of the hardest things about finishing the book was the sense that I wouldn’t get to spend as much time with them as the book was nearing its end, that I would have to leave the world of that book.

LD: Now, Rachel also asked, “Did you expect this book to connect with so many folks, especially fellow AYA” — I had to look that up, that’s adolescent and young adult — “patients and survivors?”

SJ: The short answer is no. I never expect any piece of writing to leave my laptop, let alone to find its way into the world, and part of that is intentional. I have to trick my mind into not thinking about an imaginary audience writing my words. Because as soon as I do that, I start to hear the voices of potential critics, but also to want to write in such a way that might please someone or interest someone, and I very quickly lose the thread of the truth.

I think the subject matter of this book is hard. Sure, it’s a book about cancer, but for me it’s really a book about love, about rebuilding, about these moments in life where we feel lost in transition and we have more questions than we do answers. I wondered if this book would reach an audience beyond those who had lived through an experience like cancer, and, to my great surprise, it did. And it’s the greatest gift for any writer to be read and to feel the reverberation of the stories you write and the words you write in such a way where they’re no longer yours, but they mean something to someone else and they become theirs, too.

LD: Now, Carol Tycko, who’s an undergraduate alum from the Class of 1979, she asked, “Do you see a difference in how younger cancer patients cope versus older ones, or is there a difference for the type of cancer?”

SJ: The title of the book is Between Two Kingdoms, and that’s a reference to Susan Sontag’s line about how we all have dual citizenship in the kingdom of the sick and in the kingdom of the well. But to me, the book is just as much about the in-betweenness of survivorship where maybe you’re better on paper, but the body is keeping the score of the experience you’ve been through, as it is about the in-betweenness of young adulthood where you’re no longer a kid, but perhaps you don’t always feel like a fully-formed adult. I think there is a real difference. I think age is a huge factor in how people experience illness, and to receive a diagnosis at 22 when perhaps most of your friends have not yet confronted serious illness themselves brings with it a particular sense of isolation, at least it did for me.

To confront your mortality at an age when your life is supposed to be beginning presents its own sense of paradox. I can’t speak for everyone, I can only speak for myself, but I often think of young adults as oncology’s tweens. You’re perhaps a few years too old for pediatrics, but often decades younger than the other patients in the adult oncology ward.

LD: We actually got two questions here, both about the character of Will, and I’m going to read off both because they’re from two different alums and they kind of have, similar but kind of different. I’m going to go ahead and read you what they wrote to us. You probably aren’t surprised. I bet you get questions about him a lot since he was such a huge part of the book.

OK, so Linda Morgan, who’s a grad alum from the Class of ’93, she said, “This powerful book made many grateful references to Will’s loyal and continuous care of the author during her prolonged battle with cancer. Will is not mentioned in the acknowledgements. The reader wonders if the author is still on good terms with Will.”

Then Jane Munna, she’s an undergrad alum from the Class of 2000, asks, “Have you spoken to Will since the book was published? What was his reaction to what you shared?”

SJ: Thank you for both those questions. To me, the entire book is an acknowledgement of Will. It is a tremendous privilege to have anybody by your side in an experience like this, especially when you’re not only young, but in a very young and new relationship. To me, in writing the book, I wanted to show the complexity of what can happen to a relationship under the stressors of a long-term traumatic experience like this, to show the truth about how it can bring you closer, about the ways it can break you apart. The acknowledgement section of the book, in my mind, is reserved for the people who were instrumental in the process of writing the book, and he was not involved in that process.

It’s not the first time someone has asked me that, but I’m always a little bit surprised by that question given how much he is in the book. To me, the responsibility of a memoirist is to write not only from your side of the door, but also to save the sharpest knives for yourself. So I took a lot of care in how I wrote about Will and wanting to protect his privacy as much as possible, to write about that relationship in such a way that felt balanced and true and fair while also understanding that there is an imbalance when you’re the person holding the pen, you’re telling the story from your perspective.

To answer the second question, Will and I have kept in touch. He was one of the first people to read the manuscript. Everyone who appeared in this book, it was important to me that they read the manuscript before it was published, that they have the opportunity to digest it, to provide feedback if anything didn’t sit right or felt unfair, and then, also coming from a journalism background, while a memoir is based on memory and we do not live our lives with a tape recorder on the record, to hold myself as much as was possible to that standard of journalism, so that meant using journals and email correspondence as source material, and then, when the book was finished, hiring a fact checker to go through the entire book with every single person who appeared in it.

There are a lot of interesting ethical conversations around memoir and the veracity of memory and how we hold ourselves to that and what creative license can or can’t be taken. I don’t know that there’s a right or wrong way to go about it. Different writers fall on different ends of that spectrum. But to me, it felt really important that I hold myself not only to my truth, but to the truth as much as was possible.

LD: If I can jump in with a follow-up question — which is a right that I reserve for myself as the host of the podcast — I was curious because it’s really interesting to hear about the people that you were writing about, because you’re writing about real people and their real stories. They’re theirs as well as yours. I was curious about how much of yourself you put out there, because you talk about some deeply personal things and you put it all out there for readers. I think I would personally be terrified of doing that. I’m not sure that I could. It just made me wonder what that was like and whether you, is that something that you think you ever would’ve done if it wasn’t for the cancer journey? You know what I mean? If it hadn’t been for that and your life was different, if you ever would’ve felt like you could have put yourself out there like that. Does that make sense?

SJ: Absolutely. I always wanted to be a fiction writer. It did not seem like a viable career path for someone like me who also graduated concerned with how to pay my bills and unclear about how to even begin to go about not just writing on the side, but turning that into a job, so I set my sights on journalism. When I graduated from Princeton in 2010, I wanted to be a foreign correspondent or a war correspondent. I was never interested in writing in the first person. It may surprise you to hear that I was, I am, I remain a deeply private person.

What the experience of illness changed for me was an understanding of how and when to look to the source material of my life to explore a certain idea or a question that I was interested in. I think there’s a kind of power when you dare to inhabit the first person with unvarnished vulnerability and honesty that creates a reverberation where the first person “I” quickly becomes a “you” and then a “we.” The things that I chose to share in the book I shared very intentionally. I write about things like going through menopause at 24. I think menopause is something that, no matter your age, can be hard to talk about. There’s so often a sense of shame that comes with it. But certainly at 24, that was not something that my friends were talking about or that I even had language for. Any time I share something in writing, it’s with intention.

As I was writing this book, I had a Post-It note above my desk that said, “If you want to write a good book, write what you don’t want others to know about you. If you want to write a great book, write what you don’t want to know about yourself.” So to write a book about the in-betweenness of illness, to write a book about what it means to begin again, to carry the imprints of a crisis or a trauma, and to not do that with honesty and vulnerability, for me, not only would’ve been a disservice to the book, but raise the question for me of, why write the book at all?

Toni Morrison has a great line. She says, “If there’s a book you want to read that doesn’t exist yet, then you must write it.” So I, in the aftermath of this experience, cloaked in the sense of isolation and shame, was looking for books, for poetry that was writing from that messy middle, from the trenches of uncertainty, not from some mountaintop of heroic survival or wisdom, and so I really pushed myself in ways that often felt scary and uncomfortable to write toward where the silence was.

Now that being said, there’s the draft you write for yourself, and then there are many drafts between that one and the one you share with the world. To me, I can think back on that book, all nearly 400 pages of it, and there isn’t a single memory or moment shared in there that I didn’t think very carefully about. Why is it in here? Is it gratuitous? Is it doing the work of arcing toward a question that feels central to this book? Is my life the best source material here to answer that question or is it not? There’s a version of this book that would’ve been far juicier that I could have written, but I’m not interested in sharing simply to share.

LD: Lucia Bonilla Fridlyand, Class of ’06, asks, “Can you tell us a bit more about the relationship with your parents, particularly after the cancer? They were very much your support system along with Will while you were ill. Just curious how your relationship evolved.”

SJ: One of the great privileges of being so sick — and I want to pause here and make sure that I clarify that phrasing and say that I phrase it that way not to wrap it up in some, but there’s a real clarity when you’re forced to confront your mortality. One of the benefits of that clarity for me was that I got very clear on what my priorities were and what was meaningful to me and who was meaningful to me, and it right-sized the sort of momentum with which life can take over and you find yourself filling the hours with the things that aren’t most important to you. To me, my family and I grew so much closer throughout that process. Like anyone in their early 20s, there was also a tension between that closeness and the sort of natural need to individuate, which was complicated when you become as dependent on your parents as caregivers as you’ve been from the time you were an infant. I’ve since had two recurrences.

One of the big things that’s changed in our relationship is that we no longer try to put on stoic brave faces for each other. That was the impulse the first time around. I wanted to spare my parents from the pain of something that seems to go against the natural order of things, which is watching your child not only fall ill, but confronting the possibility that you may outlive your child. They wanted to spare me of their fears. But in doing that, we were existing in our own silos. We weren’t talking about our fears, which were of course the very same fear.

When I got sick again a decade after my first diagnosis, I said to them, “Let’s not protect each other. Let’s talk about the things that we fear,” and it’s been so extraordinary to have that sort of openness of dialogue, and I think it’s allowed for a depth of intimacy, of vulnerability that I don’t know that I would’ve known to be possible had it not been for that illness.

I talk to my parents every day. They live between Tunisia, where my dad’s from, and a few blocks from where we live in Brooklyn. I’m grateful for how much time we’ve gotten to spend together as a byproduct of this illness in a way that we likely wouldn’t have.

LD: Sue Salberg, who’s the parent of an alum, asks a multi-part question. She said, “Thank you for writing this inspiring book. What does being well mean for you now? And how can we all be better caregivers? What kind of support actually helps and what doesn’t?”

SJ: I love that question so much.

LD: Yeah, me too.

SJ: So, I am back in treatment. My leukemia is considered incurable, and while my prognosis may be worse than it’s ever been, in a lot of ways, I feel like my relationship to the illness is the healthiest it’s ever been. I have grappled with illness for so much of my adult life that I think I’m now in a place where I want to give my illness exactly the time and attention it needs and not one ounce more.

When I first got the news that the leukemia was back yet again, I had this couple of weeks where I was so snowed in by fear, by this sense of doom of a Sword of Damocles hanging over my head that I didn’t know what to do with myself. I didn’t know how to function, how to make plans for the future without immediately wondering if I was going to be alive to exist in that future. The advice my doctor and a lot of people gave me at the time was, “You have to live every day as if it’s your last.”

That sort of carpe diem approach is something that I tried to do and ultimately decided was terrible advice, at least for me, because it’s not sustainable to try to make every family dinner as meaningful as possible, to make every day count as much as possible. It’s a spiritually exhausting way to live, and so I’ve had to shift to a gentler mindset of living every day as if it’s my first, which is to say waking up with a sense of curiosity and playfulness and wonder that a little kid might. Instead of crossing these big bucket list joys off of a list, what it draws me to are often the small joys, the simple joys.

So I think that’s what it means to me to live well, to be able to hold the hard circumstances of life and the joys of life, big and small, in the same open palm, to shift out of binary thinking of sick or well or happy or sad, and to allow myself not just to live in the messy middle, but to revel in it.

LD: I love that so much. All right, so before we wrap up, let me ask you, what has the reaction been like to The Book of Alchemy? I was wondering if there was a hunger out there for that tapping into creativity and expression. We’re in such a strange moment right now. I was wondering if you might’ve tapped into sort of a hunger out there for that kind of project. How’s it gone?

SJ: It’s been extraordinary to see the response to this book. I am someone who’s kept a journal from the time I was very young. Keeping a journal became a lifeline for me when I was sick and in other moments of great transition. But what I was really excited to explore in this book is, even if you’re not, maybe especially if you’re not a professional musician or artist or writer, how cultivating a creative practice, a private creative practice, in the form of keeping a journal can be not just illuminating, but sometimes perhaps even life-changing. I think we’re in a moment in the world where there’s so much noise, there’s so much uncertainty that it can feel like we’re drinking from a fire hose of uncertainty globally, nationally, personally. We’re also living in what the Surgeon General Vivek Murthy described as a loneliness epidemic and a mental health epidemic.

So, to me, this seemingly simple practice of taking a few minutes to sit down, open a notebook, and to be in conversation with yourself, to write your way back to yourself, is something that I think tapped into a need that I know I have and perhaps that many others do too. What has surprised me about the book is that some people read the book from start to finish in a narrative way. There are 100 essays and prompts in the book. Others turn it into 100-day project and faithfully journal through the 100 prompts. Others still use them as thought prompts while they’re walking or as conversation prompts around the dinner table. But what’s really amazed me is that, in response to the book, people have started forming journaling clubs all across the country and the world, and they function much like this book club in that people get together, they read the accompanying essay and write to the prompt, and they journal privately, and then they talk about what comes up.

I’m really interested in that movement between what one might think of as not just a private ritual, but the epitome of a private ritual. A journal is for you and your eyes only, unless you have a very nosy family member rifling through your notebook. But when we dare to share even a scrap of what comes up, whether it’s fear or something funny or absolutely mortifying, the end result is always the same, which is that we learn again and again that our experiences, our insecurities, our doubts are more often than not shared.

I’ve had the privilege of hosting journaling clubs in my living room. I learned things about friends I’ve known my whole life at the end of those hours that I never knew before, and I feel so connected and close to the people I’ve never met before on the other side of those hours. There’s a real need, whether it’s journaling or in some other form or rituals of reflection that allow us to process what’s happening, to commit it to ink, and therefore to memory, that allow us to notice patterns, to paraphrase the poet Rilke, live the questions and, gradually, eventually live our way into the answers, but also to do it in community.

LD: Awesome. Thank you so much, Suleika, for taking the time for this, this has really been a wonderful conversation. And thank you for your books. I think that there are just so many people, us included at PAW, we all loved reading them, we got a great response from our book group. Thank you so much.

SJ: Thank you. This has been an honor, and thank you to everyone who submitted such thoughtful questions. It’s been such a joy to talk to you.

The PAW Book Club podcast is produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode and sign up for the book club on our website paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

No responses yet