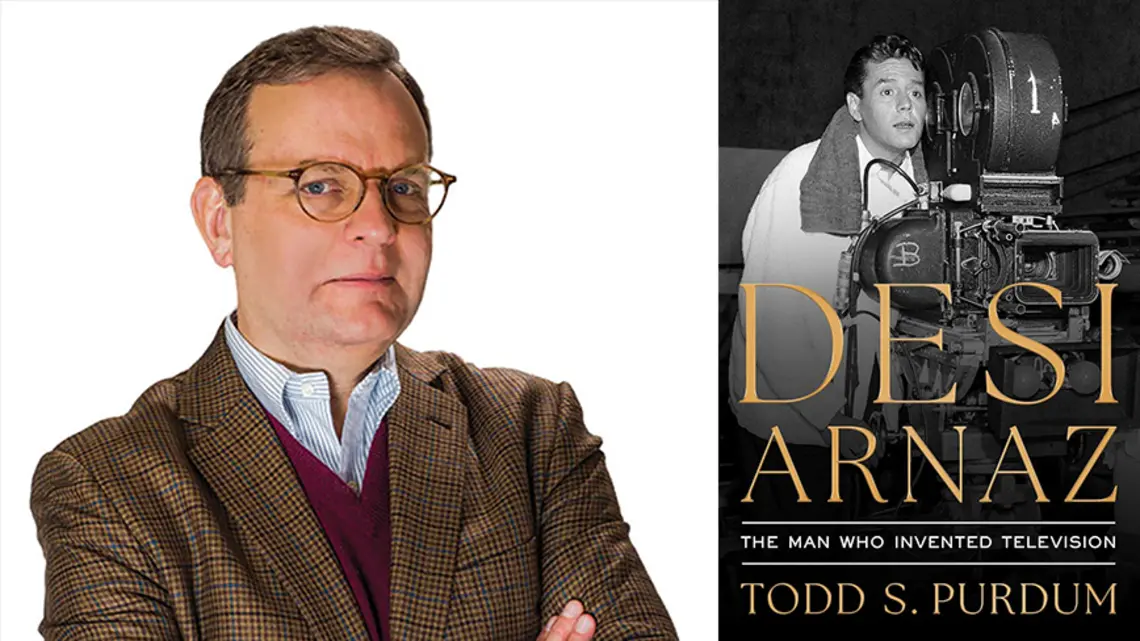

Todd Purdum ’82 Penned a Biography of Television Visionary Desi Arnaz

‘The biggest takeaway from Desi’s story for me is that talent in our country comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes, and sometimes in the most unlikely packages’

On this episode of the PAW Book Club podcast, career journalist Todd Purdum ’82 discusses his new biography of Desi Arnaz, the Cuban-born star who, Todd explains, very much deserves to be called “the man who invented television.“ Arnaz’s story hadn’t truly been done justice when, in 2020, Todd picked up the idea for a biography from his friend, playwright Douglas McGrath ’80. The book details how Arnaz’s genius changed the television industry at a critical moment, and why his innovations are the reason we all still know — and love — I Love Lucy.

Join the PAW Book Club here, and get started on our next read, Suleika Jaouad ’10’s Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of a Life Interrupted.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

This is the PAW Book Club podcast, where Princeton alumni and friends read a book together.

Today I’m interviewing career journalist Todd Purdum from Princeton’s Class of ’82 about his new biography, Desi Arnaz: The Man Who Invented Television. As Todd’s exhaustive research shows, the Cuban-born star of I Love Lucy contributed far more than his widely loved charm and comedic talent to the early television industry — many techniques and practices he pioneered are still used today. Yet his own life was a mixture of struggle and success. Todd puts it like this, “As with most people, and certainly so many high-achieving people, his strengths were bound up with his weaknesses. It was the youthful trauma of losing everything that made him willing to risk anything. The upside of his profligacy was his generosity. The flip side of his restlessness was his creativity. The corollary of his addictions was his drive. He was a genuine original, and for better and worse, he knew it.”

Todd, thank you so much for being here today and participating in the PAW Book Club.

Todd Purdum ’82: It’s my pleasure. Thanks so much. Great to be with you.

Liz Daugherty: So let’s start with a question from Susan Humphreys, who’s a graduate alum from ’79. She said, “Isn’t this story a classical tragedy? Rising high, falling low, a tragedy based on a comedy?”

TP: Yes. In a strange way it’s even more than that. It’s a story starting high, falling low, rising high, falling low again. Desi’s story is riches to rags, to riches to rags. But yes, in the sense that he was ultimately undone by his own interior flaws, it’s a classic tragedy. And the paradox of it is that at the very moment of his peak success and influence in the television industry, he fell prey to alcoholism and a compulsive kind of womanizing that perhaps grew out of the trauma he’d suffered as a teenager, losing everything in the 1933 Cuban Revolution.

But as you just said, in some ways it’s that same trauma that gave him this enormous drive to succeed. So we might not have had his achievements without his losses. And it is a terribly sad story even underneath the enormous success.

LD: So around the PAW office, we’ve been wondering where the idea for this book came from. Did something about it just interest you, or did somebody approach you to write a biography? Or wait for it, was the whole thing just an excuse to watch a lot of I Love Lucy? Which we wouldn’t blame you for.

TP: No. The whole thing is 100% Princeton-inspired production.

LD: Really?

TP: In 2020, I had lost my job at The Atlantic in an involuntary layoff during the pandemic and was looking for something to do, and I consulted my old friend, Doug McGrath of the Class of 1980 who, as many PAW readers will know, was a playwright, director, actor. He collaborated with Woody Allen on Bullets Over Broadway. He wrote the book for the Broadway musical, Beautiful, the Carole King story. And sadly, he died at 63 while he was starring in an off Broadway show directed by John Lithgow about his childhood growing up in Texas. And Doug had always loved I Love Lucy. And in fact, on the 50th anniversary of the show in 2001, he’d written a piece for The New York Times. They were twin pieces. One about Lucy, and Doug wrote the one about Desi, saying he’d always gotten short shrift.

And in 2020, it was a moment when the culture was a determined to reexamine people who maybe hadn’t gotten adequate credit in their own day. And The New York Times was running and still is running that series of obituaries called Overlooked, often about pioneering women who were not given adequate credit. And I thought that Desi’s story might be right for reexamination. And gratefully, Simon & Schuster agreed. And five years later, here we are.

LD: Was there anything that you came across that really surprised you or stood out while researching this book?

TP: Yes, I knew the basic outlines of his story. Because years ago I’d written a piece about the one street in Beverly Hills where a bunch of movie stars lived next door to each other. Jimmy Stewart lived across the street from Lucille Ball who moved next door to Jack Benny. And I’d acquainted myself with the outlines of the Lucy-Desi story. And of course, I’d grown up, like all of us in my generation, watching I Love Lucy reruns on sick days from school. Because in those days they were unavoidable on local television during the daytime hours for reruns.

And I knew the basic arc of Desi’s story from the prominent family in Cuba and so on, but I didn’t quite understand the depth of the fall that he had suffered. And also the extent of the pathbreaking contributions he made to the early television industry in terms of everything from production methods to being the force behind The Untouchables, which started as a Desilu Playhouse special in 1959. And that became the first show that really sparked a vivid debate about violence on television and the image of Italian Americans in the media, foreshadowing the debate a decade later about the making of the Godfather movie.

So I didn’t really understand just what a signal figure he was in the history of television, and that was fun to learn.

LD: So Julie Bonette, who’s our staff writer at the PAW, asked how much of Desi’s Cuban culture influenced the couple’s personal lives? Did he speak Spanish with the kids, cook any recipes from his childhood? And how did Lucy and her family feel about Desi’s Cuban upbringing and culture?

TP: Very good question. Lucy was upset that he didn’t take more time to teach Spanish to the children. She had wanted him to. And Lucie Arnaz, their daughter, told me that this would result in occasional furtive brief Spanish lessons, like before they would go to the beach when he would talk about bread and butter in Spanish and make them say a few words. But he didn’t really do it in any sustained way. He did cook Cuban recipes all the time, and he was the master barbecue chef and generally the chef for their parties, which they famously had in their early days of their marriage. They had a little ranch out in the San Fernando Valley, and it very much influenced their social life.

Lucy’s family loved Desi. They knew he was charming, they accepted him, which is a little bit surprising given the cultural differences that would’ve been in play. There’s some evidence that Lucy’s mother, Dede, in times of exasperation did apparently sometimes refer to him as, “That spic,” which is quite obviously sad. But I think he was embraced.

And he and Lucy each had responsibility for the care and feeding of their mothers for all of their adult lives. Their mothers were widowed and divorced, and that affected very much their family life, their life of their nuclear family. And then of course, Desi as a classic Latin male archetype was very much the king of the roost. And in press interviews through the years, Lucy would acknowledge that she might’ve been the prominent partner in public life, but she was the subordinate partner at home.

LD: I was curious about how much that dynamic was influenced by the time, because she did seem to play that role with them publicly and privately, and I wondered if that came from them as people or whether it was really a product of the time and the world that they were in.

TP: I think it was probably both. I think she’d been raised in the notion that she wanted to please her husband and make a home and all of that. But as you point out, society at the time would relegate each of them into those gender stereotype roles. And of course, you could make the case that even in I Love Lucy, the Lucy Ricardo character has a kind of proto-feminist streak in the sense that being stuck in the kitchen and at home is not enough for her. She’s always wanting to break out, albeit into sometimes hairbrained schemes or a career in show business and so on. But she’s not content to just be the little woman sitting at home. And that’s part of the internal attention of the show throughout its run, that she wants something bigger and more than just being a housewife.

Lucille Ball in her personal life was a demon housekeeper. She would clean the house compulsively, rearrange the drawers as a way of relaxation and for mental health. She was unable to apparently, according to all her friends and family, to easily relax and just bask and do nothing. When she wasn’t hard at work, which she was most of the time, her form of relaxation was to clean the house.

LD: Now, I’m going to be curious whether you know the answer to this one. Carol Tycko from the Class of ’79 asked, “What was Desi’s favorite way to fish, from the beach or on a boat? What type of fish did he like to catch, and did Lucy cook the fish that he caught?”

TP: I don’t know about the cooking, but Desi fished both ways. He did sport fishing, deep-sea fishing for big game fish off the coast of California on his various boats, but he also liked to fish on the beach. For grunion and other smaller fish, he would cast at night with his friend and neighbor in Delmar, north of San Diego, Jimmy Durante, and they’d be out there at dark, fishing with their poles in the dark. So he did both.

LD: What role do you think the prejudice that Desi encountered played in his struggles? Because it seems that he was up against quite a lot, much more than that typical white Hollywood producer that was out there at the time. Do you think that he would’ve had an easier time facing his demons if he wasn’t up against so much out there in the world?

TP: Yeah. I think that’s a really good question. I think he faced a combination of challenges. One was he probably, as I might’ve said a minute ago, he almost certainly suffered from what we now call undiagnosed or untreated childhood trauma or PTSD from the experiences he experienced as a teenager losing everything, watching his family’s life in Cuba be destroyed.

And then he faced overt and blatant prejudice from the industry in Hollywood, from the establishment. People were always dismissing him as this thick-accented, wacky guy who was good for a laugh. And in some ways, that worked to his advantage because people would often underestimate him at first at their peril. In business negotiations they wouldn’t understand what a keen businessman he was, what an entrepreneur at heart he was. And even though he didn’t go beyond high school, he was a very sophisticated, self-taught expert in everything from the business of entertainment to running a band, to dealing with very elite, powerful people. So I think it was a mixed bag, but yes, he suffered very real and overt prejudice because of his background.

LD: So Carol also asked, she said, “You mentioned in the book that Lucy never voted again after she was cleared of being a communist, and that Desi was very proud of being an American and was politically conservative. Did he vote regularly and was he politically active?”

TP: Yeah, my sense is he probably did vote regularly. He supported Richard Nixon, I know in 1968. Nixon ultimately named him to the unpaid and official role of goodwill ambassador for the United States to Latin America. I don’t think it really amounted to Desi’s doing anything very substantive.

But as with so many Cuban refugees from a later generation, from the Castro Revolution, Desi felt very strongly that the American system had given him every chance in the world, he was skeptical of government control of things. He also, as a self-made person in Hollywood, I think like many self-made people felt that he’d pulled himself up and other people ought to be able to do the same.

But at the same time in his memoir in 1976, Desi recalled that when he was working his first job in Miami Beach in a band in the hotel there, an immigration officer came and told him that he’d come to the United States without the proper work permit and the correct kind of visa, and that he was working illegally. But instead of deporting him, he said, “I’m going to give you 90 days to go back to Cuba, get in line, and come back in the front door the right way.” And Desi did that, and he recounted how it just goes to show there are some decent people in the world.

So I’ve been very curious, it’s impossible to know, what he would make about the current debate of immigration. But the thing that haunts me is to imagine that some place somewhere in the United States, in Florida or California, there might be some Latin genius waiting to be discovered, or whom we might not ever see because he’s been caught up in the current mass deportations. But yes, Desi was politically active and conservative in the way that many self-made people seem to be.

LD: So Julie was curious, “If nationwide live television was possible when I Love Lucy was conceived, would Desi have gone that route? And if so, do you think the show would have become the classic it is today?”

TP: I think that is the question. I think it’s a matter of weeks, really, that if a broadcast signal had been possible nationwide in the early fall and summer of 1951, I Love Lucy, might never have been produced on film. It might’ve gone out live on television and mostly disappeared and not been preserved except on maybe grainy kinescopes. And thus it wouldn’t have had the same afterlife that it has had, and we wouldn’t enjoy it in the same way we do today. It’s impossible to know, because the other thing that was happening, it wasn’t just the inability to broadcast the signal nationwide, it was also Desi’s conviction that a show that was filmed could have stronger, more durable sets, that Lucy would look better and produce a better finished product. So they may have decided to film it anyway, but it’s a really tantalizing question. Certainly the technical reason that they decided to film it was rendered moot almost the moment the show had gone on the air.

LD: So we got a bunch of questions about how you conducted your research. Dan Dasaro from the Class of ’87 asked, “I am very curious about the duration of the project from start to finish, with so much research to do interviews to conduct and travel.” And Susan Humphreys asked, “What proportion of your time did you spend on research as opposed to writing?” So how long did the process take, and how much of that was the research phase versus the writing phase?

TP: Well, from complete start to finish, it took about five years. From more active time because it took a little while to get things going and to get the cooperation of Lucie Arnaz, it’s more like three and a half years. I would say the balance was about two thirds research, one third writing time. But while I was writing, I continued to research. That’s what I tended to do with all my books. And it’s actually a useful process because once you have a draft underway, and if you continue to seek out more information, you’ll know exactly where it belongs in the narrative — something that’s much harder to figure out in the beginning. Yeah. I traveled to Cuba. I went to both Washington and New York, down to San Diego. I live here in Los Angeles. And then I would’ve been lost without the help of Lucie Arnaz who gave me access to her family archive, which she keeps in her garage in Palm Springs.

And I made several trips there to go through the papers that she has kept on file, which include everything from Desi’s high school report card to medical records, letters from a psychiatrist, his alcohol rehab discharge papers, family correspondence, drafts of his memoir, his whole FBI file, which she had gotten through a freedom of information request at one point.

So for me, the research is really the thrilling part of the process, writing is harder. And indeed, the techniques that I learned in doing my senior thesis, working in the Mudd Library in the archival papers, really have stood me in good stead for all these 43 years, in terms of my work in archives. And that’s how I first learned how to do that.

LD: Now you mentioned Lucie Arnaz, I was curious what she thought about the project. Was Desi’s family happy to have you working on this biography? Was it the story that they were hoping would be told?

TP: Yes, I think it has been a story that she always was hoping would be told. She liked to say that when people tell her how much they admired her mother, her reflexive answer is, I had a father too. And when I first approached her, she was very interested, but at the time, she felt constrained from cooperating because she was involved in an exclusive arrangement with Amazon during the making of what became Aaron Sorkin’s movie, Being the Ricardos. She felt she couldn’t cooperate under that agreement with any other project. Ultimately, that got worked out. And then she cooperated wholeheartedly and opened the doors for me to other people, family members, former associates, friends, and so on. And she just was incredibly generous, and I remain in grateful awe of her help. I couldn’t really have done it without her.

And when the book was finished, she knew we had a handshake agreement from the beginning that she wouldn’t be able to approve the book, but I promised to show her the manuscript. And when it was done, I did. And she left me a long voice memo saying that she had pictured her father reading it over her shoulder and saying at the end, “Fair enough.” And as a journalist, that’s about the perfect thing you can hope for. You never want anybody to feel that your work was unfair or that they hate it. But on the other hand, sometimes if they like it too much, you feel you might’ve missed something that would maybe make them uncomfortable, but readers ought to know. So for me, “fair enough” was a wonderful verdict and one that I am very proud to have gotten.

LD: So Dan was also curious, “How much time did you spend in Cuba and are the buildings still there or were they all destroyed in the ’33 revolution?”

TP: I was able to spend a week in Santiago. It’s hard to go between Santiago and Havana because infrastructure in Cuba is so limited and you can’t really fly on a rickety old Soviet aircraft. And yes, the house where Desi was born, the houses that he lived in are still there. One house was destroyed, a vacation house was destroyed in a hurricane some years ago. The Jesuit high school that he went to, same high school Fidel Castro went to a decade later, that’s still there. So I really felt I was able to soak up quite a bit of atmosphere.

And because of the long-standing U.S. embargo and the fact that Cuba’s a little bit frozen in time with vintage cars and all the rest, the buildings are put to different uses now. His grandparents’ house is now some kind of a community center, and they’re not private houses anymore, but the physical infrastructure of the streets and alleyways looks very much the way it must’ve in the 1920s and ’30s on the surface. And you could get a good sense of what the atmosphere must’ve been like for Desi as a young boy.

LD: Were you able to access any material that had not previously been available, or were there any hard-to-get interviews that revealed new insight?

TP: Almost all of the material that Lucie Arnaz let me have from her family had never been really made available to any author before. So that included letters from a psychiatrist that Lucy and Desi consulted in the 1950s, to drafts of unpublished material that he had written for his memoir, which didn’t make it into the final book. And I felt very lucky that way. There weren’t very many people still alive who had worked with Lucy and Desi in the heyday of I Love Lucy. But I was able to talk to Lucy’s longtime secretary, Wanda Clark, who sadly just died at 87 in retirement in Oklahoma. And Lucie Arnaz in the 1990s had made a documentary about her parents, and she conducted interviews with many, many people who were their colleagues who are no longer living, and she kept the transcript of those interviews and gave me access to all of those. So I was able essentially to quote people from beyond the grave, which was also really useful. Again, the research was a very satisfying part of the project.

LD: How has the reception been since the book was published? Have you been hearing from people who had thoughts about Desi or how he was portrayed or about the book?

TP: I’ve been very gratified to see that it’s received such a positive reception and that people seem touched by the story. People tell me how moved they’ve been by the arc of Desi’s life and the sad last 25 years of it.

But one of the things I guess I would say that sums up some of the feeling I had about the book: When I was making an appearance in Washington this summer when the book had just come out, a woman at Politics and Prose Bookstore came up to make a statement afterwards. And she said that given the current political climate in America, she wasn’t able to talk with her mother about almost anything, but I Love Lucy was something that they could still share. And I felt very touched by that.

I think one of the things that is interesting about the legacy of I Love Lucy, is that it remains a very durable artifact of our culture and of a time when a huge number, the mass 60% of the television audience on a Monday night was watching the same program, something that virtually never happens today. So in a way, excavating the story of Desi has been a return to a time when there was greater cultural unity and greater social cohesion in America. There were many injustices and other things that were not, including the prejudice that Desi faced. But it’s been nice not to think about 2025 for much of this year, I have to say.

LD: So Susan Humphreys was interested, “What is your next project?”

TP: Well, I’m hoping if I can get my act together and get a contract: Norman Lear’s widow Lynn has given me first crack at his archive, and I’d like to write a biography of Norman Lear and his work in television in the 1970s in which he revolutionized the sitcom with All in the Family, Maude, Good Times, The Jeffersons, and so on. And in some senses did for the industry what Desi had done in the 1950s, in terms of having a revolutionary impact on how television got made. Norman’s, the latter part of his career involved political activism with his group, People for the American Way, and he was very involved in opposing the rise of the religious right in the 1980s.

And it seems to me that Norman’s legacy is more relevant than ever before. In his only comment after he was suspended and before he went back on the air, his only public comment that Jimmy Kimmel on the day that he went back on the air posted on social media, on Threads, a picture of him himself with his arm around Norman saying, “Missing this guy today.” And I think that’s a really powerful image about how Norman Lear’s legacy remains with us. So that’s my goal, but I’m in the very beginning stages.

LD: That’s exciting. Well, when it’s done, what, five years from now, we’ll do that one for the book club. Well, that actually gets through all the questions that I had. Is there anything else you’d like to add or anything you’d like people to know about this project?

TP: No, just that I think it is really worth remembering. The biggest takeaway from Desi’s story for me is that talent in our country comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes, and sometimes in the most unlikely packages. And one of the things that Desi in his career and his life exemplified is he never took no as the final answer. If an obstacle came in his path, he found a way around it. So when CBS and prospective sponsors didn’t think he could plausibly play the wife of the redheaded American girl in I Love Lucy, he arranged to take them on a vaudeville tour around the country. And he and Lucy performed comedy and music together and showed that audiences would lap it up and love them, which is what they did. When Lucy was pregnant in real life with their son, Desi Jr., and CBS said, “You cannot have a pregnant woman or a pregnant character on the air,” they realized that Lucy Ricardo could have a baby, and it would be a wonderful, poignant touching series of episodes.

And Desi ultimately facing resistance from Philip Morris, the sponsor, wrote directly to the chairman going over the heads of the executives at CBS and the advertising agency and everybody else. And saying, “We’ve given you the number one show on television. If you don’t want us to be responsible for it anymore, then we can’t be, and you’ll have to deal with it yourselves.” And suddenly, the opposition to the show dissipated overnight, and only a couple years later did Desi found out why. He went to visit Philip Morris, and the chairman’s secretary showed him a memo that he had sent to the staff saying, in pungent Anglo-Saxon terms that I’m not going to say on the podcast, “Don’t fool around with the Cuban.”

And I think Desi’s lesson is one of the oldest lessons of your childhood and your parents and your teachers: If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. And he’s a proof positive of the power of perseverance.

LD: All right. Well, this has been fantastic. Thank you so much for taking the time for this.

TP: Thank you so much for having me. My pleasure. And I’m delighted to be here.

The PAW Book Club podcast is produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode and sign up for the book club on our website paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

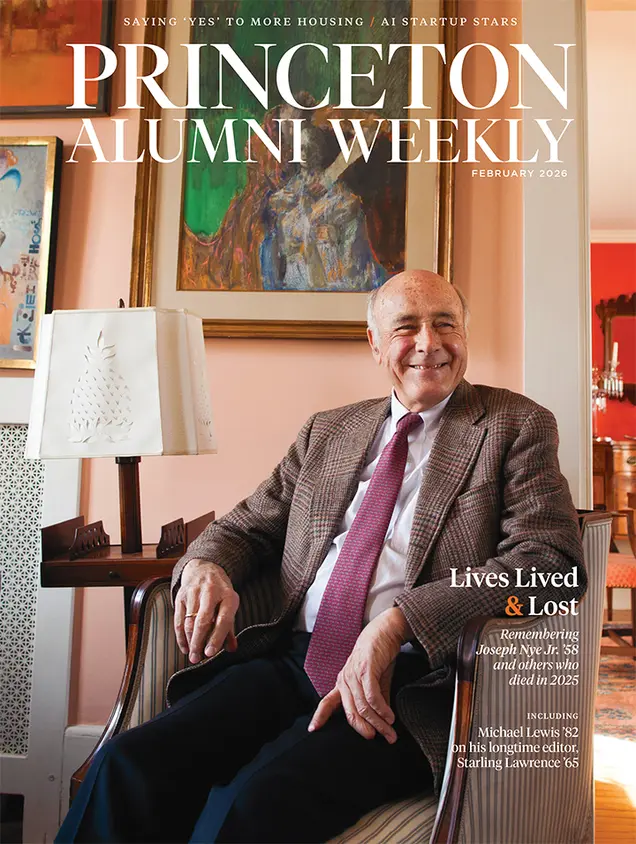

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet