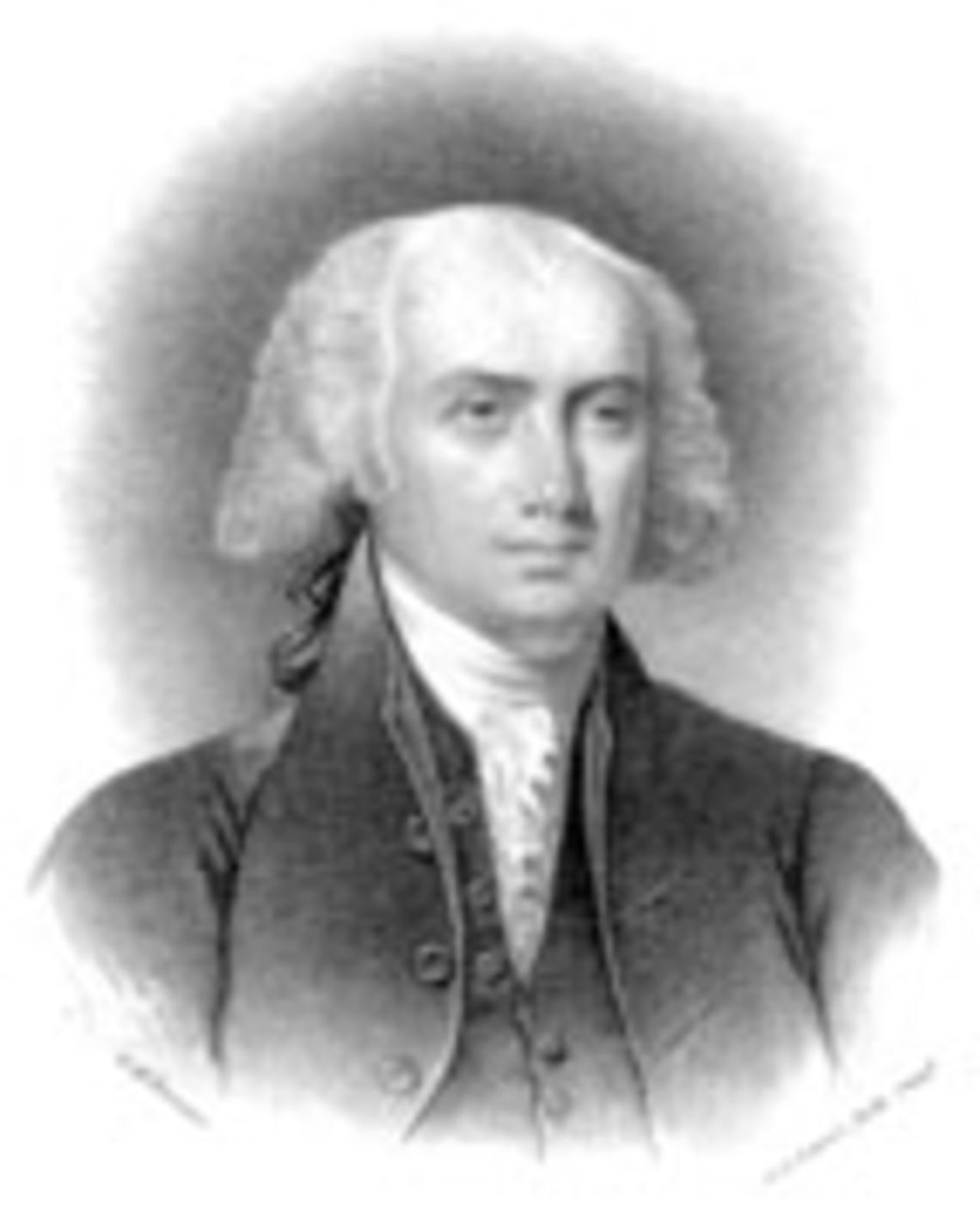

#1: James Madison 1771 (also considered Princeton’s first graduate student)

“An astonishing ratio of mind to mass”

I am writing this wee tribute to the greatest Princetonian on a morning that began, as most of my mornings do, with a predawn walk accompanied by my dog. His name is Madison. I am wearing my favorite necktie. It is blue, with silver profiles of James Madison. Later this morning I shall work on a book I am writing. It is to be titled The Madisonian Persuasion. I am not one who needs to be persuaded that Madison merits being ranked as Princeton’s greatest gift to the nation.

Before I turned to journalism — or before I sank to journalism, as my father, a professor of philosophy, put it — I was, briefly, a professor of political philosophy. I cheerfully accepted that I never would be nearly as original and consequential as the philosophic Madison had been. Then I became a newspaper columnist, a role in which I always have known that I could never be nearly as original and consequential as was Madison, America’s foremost columnist.

The Federalist Papers, of which Madison wrote the two most important, were, of course, columns written to advance the ratification of the Constitution — in whose drafting Madison was the most subtle participant. If a student of American thought fully unpacks the premises and implications of Federalist 10 and 51, that student comprehends not only this nation’s political regime but also the Madisonian revolution in democratic theory.

Before Madison, almost all political philosophers who thought about democracy thought that if — a huge “if,” for most of them — democracy were to be feasible, it would be so only in a small, face-to-face society, such as Pericles’ Athens or Rousseau’s Geneva. This was supposedly true because the bane of democracies was thought to be self-interested factions, and only a small society could be sufficiently homogeneous to avoid ruinous factions.

But America in the second half of the 18th century, although small compared with what it would become, was in size already a far cry from a Greek polis. Besides, Americans had spacious aspirations. A small nation? They were having none of that. At a time when 80 percent of them lived on a thin sliver of the eastern fringe of the continent, within 20 miles of Atlantic tidewater, what did they call their political assembly? The Continental Congress. They knew, more or less, where they were going: California.

Madison understood the need for philosophic underpinnings for an “extensive republic,” a phrase that seemed oxymoronic to others. He can be said to have had a political catechism, which went approximately like this:

What is the worst outcome of politics? Tyranny.

To what form of tyranny are democracies susceptible? The tyranny of a single, durable majority.

How can this threat be minimized? By a saving multiplicity of factions, so that majorities will be unstable and transitory.

Hence in Federalist 10 he wrote that “the first object of government” is “the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property.” From these differences arise different factions in their freedom-preserving multiplicity.

Having said in Federalist 10 that “neither moral nor religious motives can be relied on as an adequate control” of factions, Madison turned, in Federalist 51, to the institutional controls established in the Constitution — “this policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives”:

“Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. ... It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. ... You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself.” In a masterpiece of understatement, Madison said, “Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” No kidding. And Madison did not mince words regarding those about whom no one nowadays dares to say a discouraging word — “the people.”

“There is,” he said, “a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust.” Let the record show that once we had a president who had spoken of the voters’ depravity. Those were the days. Madison did qualify his astringent judgment about the people by acknowledging that there “are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence.” But notice the carefully measured concession to the public’s sensibilities: “a certain portion,” indeed.

In 1976, the nation’s bicentennial, the presidency was won by someone who, pandering in the modern manner, promised to deliver government “as good as the people themselves.” One can imagine Madison muttering, “Good grief!”

In Washington, the seat of the government that he did so much to design, there is no monument to Madison comparable to the glistening marble temples honoring Jefferson and Lincoln. There is, however, a splendid Madison Building, which is part of the Library of Congress. It was said of the 5-foot-4 Madison that he contained an astonishing ratio of mind to mass. So it is altogether right that Madison, physically the smallest of the Founders, is honored in his nation’s capital by a repository of learning.

My next dog, if female, will be named Dolley.

Columnist George F. Will *68 won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1976. In addition to writing his regular column for Newsweek and a column that appears in 450 newspapers, Will is a regular contributor on ABC’s This Week on Sunday mornings.

No responses yet