A 14.7% investment return as Princo 'stays the course'

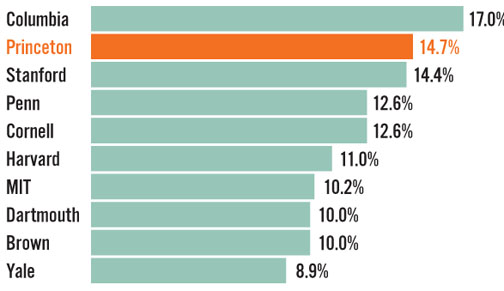

Princeton’s investments grew 14.7 percent in the year ending June 30, rebounding from the heavy losses suffered during the financial crisis and outpacing all but one Ivy League school.

The endowment stood on June 30 at $14.4 billion, which is $1.9 billion less than it was at its height in 2008. Princeton’s investments lost 23.5 percent of their value in 2008–09, leading to $170 million in spending cuts over two years.

Princeton University Investment Company president Andrew Golden, who oversees the endowment, said the 2009–10 return affirms the University’s long-standing practice of investing for the long term without overreacting to near-term swings in the market. “We recognized there would be extreme environments,” he said in an Oct. 21 interview with PAW. “So we stayed the course. Sticking with the plan is actually responsible for the solid results this year.”

The investment success of the past year means the endowment could exceed its 2008 high of $16.3 billion in less time than some University officials believed it would take. In fact, the University says it may take as few as two years if Princeton enjoys returns in the low teens during that period.

Factoring in the 2010 return, Princeton’s average investment growth over the past decade has been 7.9 percent, well above the performance of broad equity indexes like the Standard & Poor’s 500.

The endowment pays for about half of Princeton’s annual operating budget, and the 2010 return brings back into alignment the University’s long-stated spending strategy. This calls for 4 to 5.75 percent of the endowment to be spent each year. In 2009–10, the figure was 6.04 percent — meaning Princeton was spending more of its endowment than it wanted. This year, the figure is expected to be 5.1 percent.

Despite the improvement, the University says it is continuing to practice spending restraint. Departments are planning for a 3 percent boost in endowment payouts in 2011–12, down from the 5 percent annual increases that most expected before the financial crisis.

The biggest driver behind the endowment’s growth was investments in private equity — companies that are not traded publicly on any open market. More than a third of the endowment is in private equity, which returned 18.6 percent last year, as companies were sold or had shares sold on the open market.

Other areas in Princeton’s endowment fared well, too: emerging-market stocks (43.1 percent increase), domestic stocks (22.5 percent), developed-country stocks (11.2 percent), and bonds (6.4 percent). A class of investments known as independent return — funds that bet on specific circumstances, such as whether a company will file for bankruptcy protection — increased by 15.8 percent.

The only loser was investments in real assets — commodities like oil, timber, and real estate — which lost 1.6 percent. That was largely a result, Golden said, of declines in the value of investments in private real estate such as office buildings, apartment complexes, and hotel properties.

During the financial crisis, the University could have liquidated its private-equity holdings, which are not easy to sell during market panics, at depressed prices to raise needed cash. Instead, in January 2009, the University opted to borrow $1 billion at attractive interest rates. Golden said he is pleased with the decision, given the success of private-equity investments in the past year.

Still, the volatility of the past two years has created fluctuations in the endowment. Golden’s goal is for private equity to make up only 23 percent of the endowment. But as the value of private-equity investments grew and other types of investments declined, private-equity investments came to represent more than 35 percent of the endowment.

Golden will seek to reduce the University’s private-equity holdings down to target levels over three years or so, a process that will include winnowing the number of private-equity funds the University uses from 70 to 35. Other asset targets include: independent return (25 percent of holdings), real assets (23 percent), emerging-market stocks (9 percent), domestic stocks (7.5 percent), developed-country stocks (6.5 percent), and bonds (6 percent).

In the wake of the market chaos, Golden and others at the University discussed creating a fund that would serve as an easy source of cash during a crisis. This liquidity fund would act as a buffer against Princeton’s overarching strategy of locking up capital over long periods of time. The University says this fund will be created in 2011 after Princeton finishes drawing down the $1 billion bond issuance this year, of which $240 million remains.

How Princeton’s investment return for the past year compared with some of its peers:

No responses yet