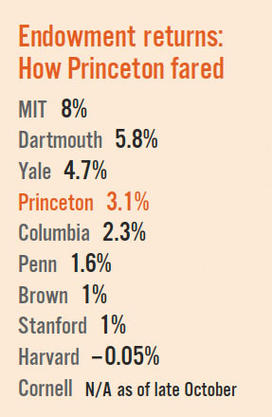

3.1% return for endowment as its value shrinks slightly

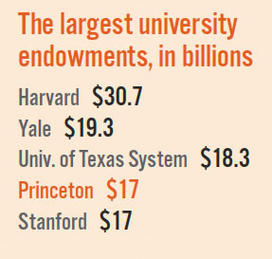

The Princeton University Investment Co. reported Oct. 19 that the endowment earned a modest 3.1 percent gain in the year ending June 30. The endowment was worth $17 billion – $100 million less than a year earlier — after taking into account investment returns, gifts received, and spending from the endowment.

In many years, Princeton’s strategy of investing in ownership of energy reserves and directing a bigger pool of its endowment to developing countries generated huge returns. Last year the tables were turned, as energy prices fell and foreign markets fared poorly.

The results are a sharp contrast from the University’s performance in 2010–11, when the endowment soared nearly 22 percent to an all-time high of $17.1 billion. That surpassed the peak achieved before the financial crisis and recession sliced about a quarter off the endowment’s value. The endowment is especially important because it provides a substantial amount of Princeton’s operating budget — 47 percent this year.

By this time last year, University officials knew that they were in for a year of rough sledding — with intensifying concerns about the pace of the U.S. economic recovery, Europe’s worsening financial crisis, and a slowdown in fast-growing economies like China’s. Under these circumstances, Andrew Golden, president of Princo, described the endowment’s returns in a PAW interview as an achievement.

“It’s reasonably solid, given the environment of the last year,” he said. “Markets were fickle, if not downright mean-spirited. ... Particularly if you were involved in anything outside of the U.S., you faced a headwind.”

Golden said the results do not affect the University’s overall strategy, which is to diversify in a broad array of investments domestically and abroad, with hopes of generating a return of about 10 percent per year.

The steady-as-she-goes strategy comes more than three years after the University was hit hard by the financial crisis, as the endowment lost about 23.5 percent of its value in 2008–09. Princeton cut $170 million in spending over two years and scaled back its capital plan.

Today, despite continued control over budget growth, the belt-tightening is over. “We are not anticipating any additional cuts, and we are focused on selective investment and resource allocations to continue to advance the University’s mission,” said Princeton spokesman Martin Mbugua.

Princeton has created a $100 million “rainy-day” fund, separate from the endowment, to help in case of a shortfall, but the administration expects a balanced budget in coming years.

Some other universities are beginning to reduce spending in an area where Princeton has led: financial aid. Cornell recently said it would require students whose families earn more than $60,000 a year to help pay for their education by obtaining loans from the government and other sources. MIT said it would require low-income students to increase their contribution. Princeton, meanwhile, increased its financial-aid budget for this year by 5.6 percent, to $116 million.

The University spent 4.4 percent of its endowment last year, in the middle of a spending-target range of 4 percent to 5.75 percent. The spend rate for this year is expected to be 4.7 percent. As the endowment declined several years ago, the University breached the upper range, hitting 6 percent in 2009–10.

In the past year, Princeton saw some of the traditional drivers of its investment success become drags instead. The biggest winners the previous year, for instance, were investments in fast-growing emerging markets such as China and India, as well as investments in stock markets in developed countries outside the United States. Going into that year, Golden had increased the endowment’s allocation to emerging-market countries.

But both types of investments did poorly in the year ending June 30. Emerging-market stocks returned only 0.2 percent, while developed-country equities lost 9.7 percent. Also performing poorly were real assets — such as the ownership of energy resources that have become a staple of Princeton’s strategy — which returned just 1.4 percent.

Other investment types did somewhat better. Fixed income and cash returned 2.4 percent, private-equity investments yielded 2.7 percent, and a class of specialized funds that invest based on specific conditions, known as independent return, had a 4.3 percent bounce. The biggest winner was U.S. stocks, with a 5.9 percent return.

Princo is not altering any of its investment targets, though the actual allocation may vary due to market fluctuations. A third of the portfolio is directed to private-equity investments, and another 25 percent goes to independent-return funds. Real assets, such as natural resources and real estate, get 23 percent. The University invests 11 percent of its assets in emerging-market stocks, 5.5 percent in developed-country stocks, and 6.5 percent in U.S. stocks.

The 3.1 percent return is the lowest in the past decade except for 2008–09. Still, the return brings the University’s 10-year average up from 9.8 to 9.9 percent. That’s because the average no longer includes the fallout from the 2001–02 burst of the dotcom bubble and the impact of the recession that followed.

No responses yet