FitzRandolph Gate, the official entrance to the University campus, stands at the top of Witherspoon Street, the main artery of Princeton’s historically African American Witherspoon neighborhood. And for much of the 20th century, that imposing wrought-iron portal wordlessly conveyed an unmistakable message about the University’s relationship with the black community.

“That gate was always locked shut. It was never open — never,” Leonard Rivers, who grew up in Princeton and later coached football and baseball at the University, recalls in a new book about the neighborhood. “We knew that when you crossed Nassau Street and you went to the University, that was not us.”

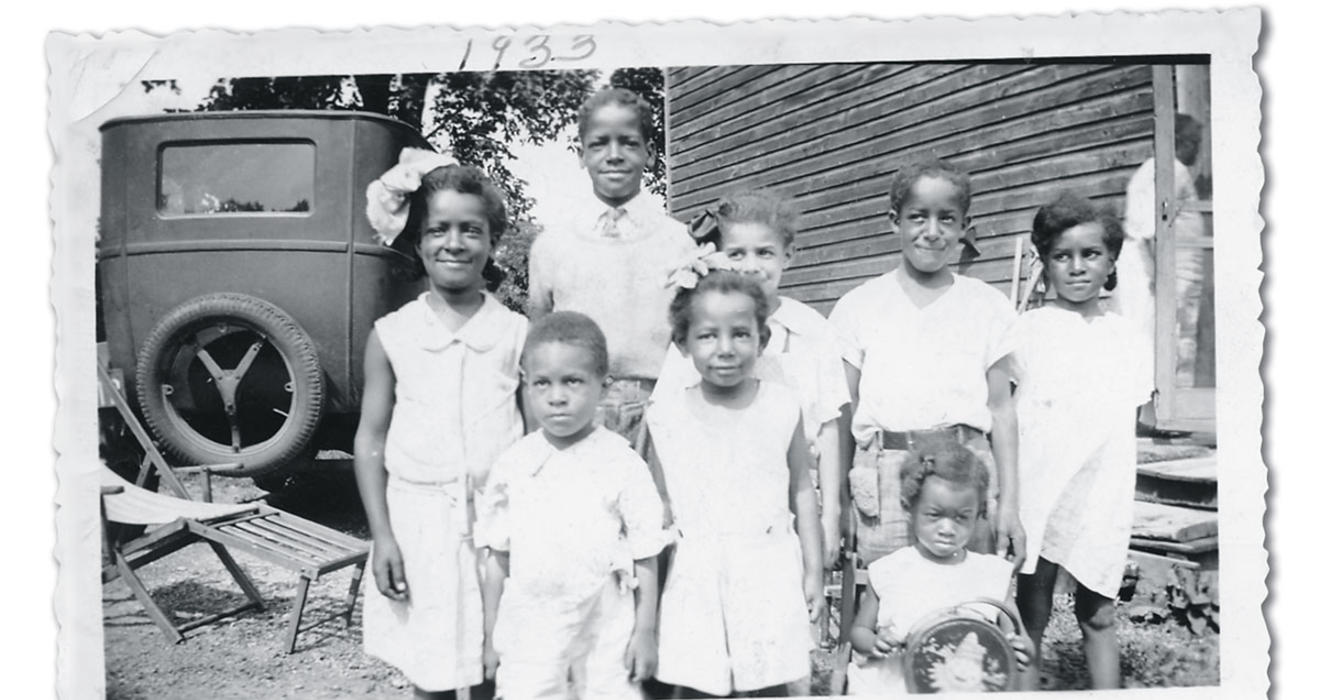

Rivers is one of dozens of Witherspoon residents who tell their stories in I Hear My People Singing: Voices of African American Princeton, an oral history of Princeton’s three-centuries-old black community that Princeton University Press will publish in May. The book brings to vivid life the working-class neighborhood’s experiences of racism and segregation, as well as the strong bonds of community that helped residents survive in what was often called “the North’s most Southern town” or “the South’s most Northern town.”

The book is based largely on interviews that three dozen University students conducted between 1999 and 2002, initially as an assignment for two writing courses taught by journalist and author Kathryn Watterson. Watterson, who now teaches in the University of Pennsylvania’s creative writing program, excerpted her Princeton students’ interviews, organized them into thematic chapters, and wrote introductions placing the residents’ stories in historical context.

“The life stories are so powerful because of what they’ve lived through, because of the experience of having to deal with all the prejudice,” says Watterson, who spent years searching for a publisher for the book. “The positivity and the bigness of it is contagious. The kids fell in love with these people.”

Watterson’s own interest in race and civil rights is lifelong: Driving from Arizona to Florida in 1964, as a 22-year-old bride, she encountered Jim Crow segregation for the first time. “The first day I saw the colored and white water fountains and the signs on the doors, it just threw my world upside down,” says Watterson. “The whole trip across the South was radicalizing. The injustice was so great.”

Watterson went on to tutor African American children; volunteer in the Peace Corps; cover race, policing, and anti-war activism in Philadelphia; and publish a nonfiction book about women in prison, before moving to Princeton in 1987. The oral-history project was suggested to her by longtime Witherspoon resident and educator Henry F. Pannell, 77, who feared that the stories of the neighborhood’s aging residents were going to die with them.

Initially, not every resident wanted to participate in a University-linked project. Some remembered how town and gown had collaborated in the middle decades of the 20th century to demolish black-owned homes and businesses in order to redevelop Nassau Street. Some resented what they saw as past misrepresentations of their poor but striving neighborhood as a ghetto.

But others welcomed the chance to set the record straight about their community’s courage, resilience, and vibrancy.

In the 1940s and ’50s, “on my street alone, nobody was making over $100 a week, but 38 people from Birch Avenue, African American children, became teachers,” says Romus Broadway, 78, who has immortalized his neighborhood in dozens of photographic collages. “The parents got so little recognition for what they were doing. They kept the faith. Everything that is written about what makes a parent successful was here, but it was never illuminated.”

Princeton’s African American community is older than the University: The first free blacks arrived in town in the 1680s, some 70 years before the College of New Jersey relocated there. The oft-told tale that Princeton’s original black residents were the slaves of University students from the South is a myth, Watterson writes.

But the University’s first eight presidents were all slaveholders — including the sixth, neighborhood namesake John Witherspoon, a Presbyterian minister who eventually preached in favor of abolition but at his death still owned two slaves. By 1850, decades after New Jersey abolished slavery, as many as 20 percent of Princeton’s 3,000 residents were free African Americans.

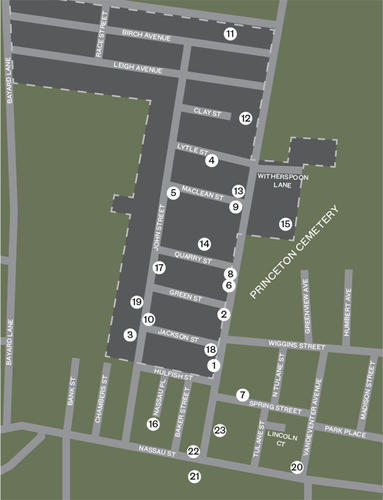

They settled in a neighborhood north of Nassau Street, formerly 18 blocks but now an 11-block, L-shaped enclave bounded by Witherspoon and John streets; Paul Robeson Place, formerly called Jackson Street; Leigh and Birch avenues; and Bayard Lane. The neighborhood is sometimes called John-Witherspoon or Witherspoon-Jackson, after its main streets.

As the town’s black population grew, so did the University’s Southern enrollment. Princeton courted Southern students unwilling to venture into the abolitionist New England of Harvard and Yale. At its peak in 1848, the proportion of Southerners in Princeton’s student body was 51.5 percent, Watterson reports, and it remained at or above 40 percent well into the 20th century.

Perhaps as a result, racial attitudes in Princeton had a distinctly Southern flavor. “Rich Princeton was white; the Negroes were there to do the work. An aristocracy must have its retainers, and so the people of our small Negro community were, for the most part, a servant class,” wrote one of the most famous products of the Witherspoon neighborhood — singer, actor, and civil-rights activist Paul Robeson. “Less than 50 miles from New York, and even closer to Philadelphia, Princeton was spiritually located in Dixie.”

I Hear My People Singing — the title is based on a Robeson quote — documents the myriad ways Princeton enforced racial separation, in some cases even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made the segregation of public accommodations illegal.

Nassau Street stores and restaurants limited or denied service to African Americans, and black men couldn’t get haircuts in the barbershop. The hospital refused to give black doctors admitting privileges, and Nassau Presbyterian Church and the Garden Theatre relegated African Americans to balcony seating. In 1937, the Nassau Inn declined to rent a room to African American opera singer Marian Anderson; she accepted Albert Einstein’s invitation to stay at his house instead.

But the discrimination was not always as overt as in states farther south. Stores that were off-limits to African Americans did not display a “Whites Only” sign, “but if you went in, you were kind of ushered out,” says Jacqueline Swain, 72, who works in administrative support at the University’s Program in Teacher Preparation. “They didn’t do it with axe handles or police dogs.”

That relative subtlety could make navigating life in Princeton tricky for African Americans, Witherspoon residents note in Watterson’s book. “One thing about the South, you don’t have to wonder,” neighborhood resident Albert Hinds, who died in 2006 at the age of 104, says in the book. “Down South you know: I can’t go here, I can’t go there, I can’t do that, I can’t do this. Here it’s more difficult; you don’t know whether you can or not.”

Witherspoon parents sought to shield their children from the ugliness that might greet them if they ventured onto Nassau Street — the area that whites called “downtown” but blacks knew as “uptown.” “As a child, I never gave it much thought. Our parents didn’t allow us to go uptown, and so we didn’t go,” says Penelope S. Edwards-Carter, 69, who later served as Princeton’s first African American borough clerk. “It wasn’t a matter of consciously thinking it was because it was segregated as much as your parents just didn’t let you go.”

Because African Americans were unwelcome in so many places in white Princeton, they built thriving businesses of their own: stores, clubs, bars, beauty shops. “There was a viable, vibrant microeconomy that happened in spite of segregation,” says Swain.

The most important of these separate institutions was the public school system. Princeton High School was integrated in 1916 — although African American students received certificates of completion, rather than diplomas — but schools serving younger students remained segregated by race until New Jersey’s 1947 constitution outlawed the practice.

Princeton’s African American schools were shortchanged of money and materials, but in Watterson’s book, Witherspoon residents share fond memories of their black teachers, who knew their students from the neighborhood, treated them with love and respect, and had high expectations for their success.

“That was one of the best educations you could get, even though it was segregated, even though we had second-class books,” says Pannell, who attended the Witherspoon Street School for Colored Children through fourth grade, when the schools were integrated. “They were dedicated to seeing that we got the best education.”

Although some Witherspoon residents report positive experiences with white teachers and classmates after Princeton integrated its schools in 1948, many do not. “The way those teachers treated us, I’ll never forget,” Pannell says. “They wouldn’t call on you, they ignored you, and you knew that they didn’t want you there.” Within three years of integration, Watterson writes, the graduation and college-attendance rates of African American students fell precipitously.

Even those Witherspoon residents who finished high school knew that their college plans could not include attendance at the hometown university: Princeton did not enroll African American students until World War II, and then only a handful. Most members of the black community knew the University less as an academic institution than as an employer. “When you finished high school, there were jobs waiting for you as a waiter or a dishwasher or a cook, but not as a student,” Broadway notes in Watterson’s book.

In 1939, a one-time neighborhood resident named Bruce Wright was offered a scholarship to the University, but when he arrived for the start of classes and officials realized he was African American, they revoked his acceptance. When Wright demanded an explanation, then-Dean of Admission Radcliffe Heermance wrote him a letter saying that while “Princeton University does not discriminate against any race, color or creed,” the presence of so many Southerners on campus and the absence of other black students “would enforce my advice to any colored student, that he would be happier in an environment of others of his race.”

Wright, who died in 2005, graduated from Lincoln University, a historically black school in Pennsylvania, earned a law degree from New York University, and eventually became a New York state court judge. “But I’ve never forgiven Princeton for what they did,” he says in Watterson’s book.

The University’s troubled relationship with the African American community began to improve in the 1960s, Watterson says, when President Robert F. Goheen ’40 *48 first heard stories like Wright’s. “He was so shocked by the racism,” Watterson says. “We’re such a segregated society — it’s not unusual not to know what’s going on.”

In 1968, as Goheen sought to diversify the University, he offered the job of assistant dean of students to a Witherspoon resident, Joseph P. Moore. As Moore recounts in Watterson’s book, his father, a longtime University groundskeeper, was unimpressed by the prestigious appointment. “That’s a plantation, son,” he said. “Why would you want to work there?”

A year after Moore took the job, becoming one of Princeton’s first black administrators, the Princeton Class of 1970 marked its graduation by persuading the University to permanently unlock FitzRandolph Gate. Decades later, the University gave Watterson financial support for her oral-history project, which she likens to a local version of the truth commissions designed to heal the wounds of divided societies. “We need to look at racism in the face,” she says. “We need to look at how we’ve hidden from it and how it’s been hidden.”

Princeton students who participated in Watterson’s project — now alumni — say the interviews they conducted enriched their sense of the sometimes-invisible world beyond the University’s gates. “It makes you understand that there’s parts of that history that don’t get told very often,” says Saloni Doshi ’03, now a Denver business consultant with a social-justice specialty. “It makes you realize how sheltered you are as a student.”

For A-dae Romero-Briones ’03, who grew up on the Cochiti Indian reservation near Santa Fe, N.M., the oral-history project allowed her to connect with others who had experienced the racial slights she sometimes encountered as a dark-skinned person at a largely white University.

“I had a really hard time at Princeton. It was such a culture shock for me,” says Romero-Briones, now a food and agriculture attorney in Hawaii. “But knowing that there was a community outside of those gray walls helped me feel more at home.”

Watterson taught her students to listen empathetically to the stories of others’ lives, and “in this political time, it feels more important than ever to have these stories,” Doshi says. “You build solutions by understanding people’s stories, and not through charged political dialogue.”

Indeed, Pannell says he always hoped the project might forge such empathetic connections. “I just thought that one day, maybe one of those kids might become president, or in a position where they would remember that they had met a group of black folk, which they had never been around before, and that would have some kind of positive influence,” he says. “Maybe this whole world could change just by getting to know people.”

Today, longtime residents’ memories of the Witherspoon neighborhood are tinged with melancholy. The place they remember is rapidly disappearing, they say, a victim of larger socioeconomic pressures. In the 2010 U.S. Census, the African American population of what was then Princeton Borough (it has since merged with Princeton Township) totaled only 7.5 percent; by contrast, the Latino population was 10.3 percent.

In part, the demographic changes are a relic of Princeton’s racist past, an era when neighborhood children often left town once they grew up. “When African Americans went to college, they became unemployable in Princeton,” says Broadway, the photographer. “So they went to other places that would take them in and recognize their ability.”

But gentrification is also at work. High property taxes are pushing out lower-income homeowners, and Witherspoon’s convenient location, within walking distance of Princeton’s amenities, tempts higher-income buyers. “The neighborhood has disappeared to a great degree,” says Edwards-Carter, the former borough clerk. “People are hanging on by the skin of their teeth.”

Settling a legal challenge by residents to its tax-exempt status in October, the University agreed to contribute $10 million over six years to a fund for low-income homeowners. It also allocated $1.25 million over three years to the nonprofit Witherspoon-Jackson Development Corp., which helps economically disadvantaged residents repair and keep their homes. Earlier, in April 2016, the municipality designated the neighborhood a historic district, to prevent purchasers from tearing down older residences and replacing them with out-of-scale mansions. Residents say it remains to be seen whether the new designation will make it easier for old-timers to stay.

The overt segregation that once shaped life in Princeton has disappeared, but Witherspoon residents say a subtler racism remains a fact of life for African Americans: the store clerks who treat black customers with suspicion, the partygoers who mistake black guests for service staff, the schools where African American students are too often tracked into less rigorous classes.

And many lament the demise of an older way of life, a small-town ethos that a bigger, busier Princeton has lost. “You don’t have that same close-knit cohesiveness that existed when we were children,” says Edwards-Carter. “You don’t have that same sense of neighborliness. People live next door to each other now and they don’t even know each other.”

The publication of Watterson’s oral history, residents say, will help preserve the memory of a place that nurtured generations of African American children and provided a sustaining bulwark against racism: “Just to know that we were here, that Princeton did have an African American community,” says Swain, of the teacher-preparation program. “A vibrant, healthy, well-informed African American community.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, N.J. Her most recent book is Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom.

The Borough of Princeton in 1917, based on a map created by William L. Ulyat

1. Griggs’ Imperial Restaurant

2. The Colored YW/YMCA

3. Dorothea House

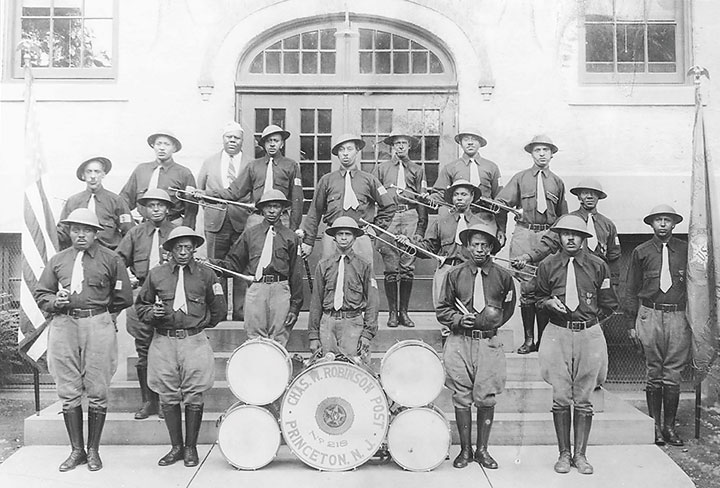

4. Charles Robinson American Legion Post 218 (below)

5. Masonic Temple, Aaron Lodge #9 Inc.

6. Paul Robeson’s birthplace

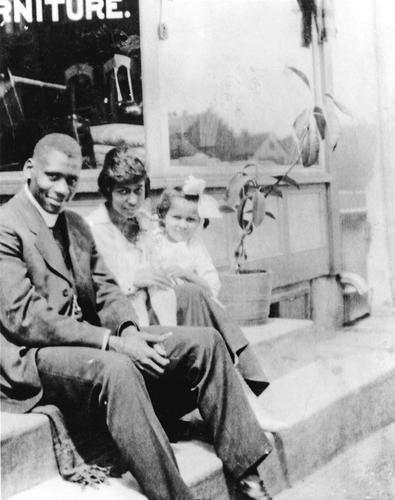

7. “Sport” Moore’s family property (below)

8. Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church

9. Mt. Pisgah A.M.E. Church

10. First Baptist Church of Princeton

11. Morning Star Church of God in Christ

12. Barclay’s Ice, Coal, and Wood Plant

13. Witherspoon Street School for Colored Children (below)

14. Witherspoon (“Quarry Street”) School

15. Negro Cemetery

16. Baker’s Alley (site of Palmer Square after 1937) (below)

17. Ball’s Confectionery

18. Thomas Sullivan’s grocery store (below)

19. Princeton Rug Washing and Carpet Cleaning Works

20. Public Library (later the Historical Society)

21. Nassau Hall and FitzRandolph Gate

22. Cesar Trent’s property (1795)

23. Office of the Citizen

In April 2016, the area inside the dashed line on the map was designated a historic district on the recommendation of the Historic Preservation Committee of Princeton.

19 Responses

Edward Benson ’63

4 Years AgoUrban ‘Renewal’

I was working in town in the summer of '62, and used to go across Witherspoon Street to a local lunch place. The restaurant made a specialty of serving what the owner caught the night before, especially blue fish. One day, he told me in passing that he would be closing shortly for good. I expressed surprise and disappointment, and asked him why. He was a middle aged Black man, and I think he knew I was a Princeton undergrad. He gave me a sharp look, and explained that he was going to open a gas station. I repeated my disappointment, and he said "I'm going to open a gas station. Because I am 'improving' the location, and got bank financing for it, the town is blocked from using eminent domain to condemn not only this place, but the neighborhood down Witherspoon Street to the township line.

I grew up in town, but had not realized that "Palmer Square" was an urban renewed neighborhood formerly part of the Black community in Princeton. I had never thought to wonder how a collection of unrelated stores around Palmer Square came to be situated in a single stone building that would not have been out of place in the English Cotswolds. I am embarrassed to confess I had grown up in Princeton thinking of it as a refuge from the racial conflicts then starting to convulse the North. I had also gone to Andover, and did not think it strange that there were three Black students in my class of 200 (and roughly the same proportion in my class at Princeton).

Elizabeth Chen

5 Years AgoPrinceton’s Black community

Article mentions weekly salary in the Black community of barely $100.00 week in the 1940s. This would have been over the U.S. media income of $2,600 a year!

Roy Scudder-Davis ’73

6 Years AgoA Part of Family History

I have been holding onto the issue of the Princeton Alumni Weekly where the article "Across Nassau Street" appeared. The article was quite interesting to me because both my mother and father grew up in Princeton, NJ. My paternal grandfather worked in one of the eating clubs, and a maternal uncle was part of the custodial staff, even when I was a student at Princeton. Apparently my parent knew Paul Robeson as one of the kids in the neighborhood.

Part of the article talks about African Americans being able to work at the University, but not being able to attend. I guess that accounts for why it was so important for my parents to see me attend and graduate from Princeton University. My paternal grandparents and several aunts lived on Clay Street and attended Mount Pisgah A.M.E. church before, during, and after the time I attended Princeton. In true family form, it only became obvious to me how important my graduation from Princeton was to the family after I had accomplished it. A family get-together on Clay Street on the day of my graduation was when I found out -- a typical no-pressure, but high-aspirations attitude.

This response is a bit late in coming, but thanks for writing part of my family history for everyone to read.

Cynthia Williams

8 Years AgoRemembering a Beautiful Childhood

I am a descendant of Elma Lambert and Donald Lambert. With pride I call their names, Aunt Virginia, Aunt Sugie, and hello Penelope. The article brought me back to a beautiful childhood.

As a teen I would commute from Trenton to Princeton to work at the youth center. I also worked washing test tubes for the laser program, at Princeton U., a teen summer program. I was recently in Princeton, and my soul yearned to be young again. This was a wonderful article. Pride up and down John Street. I smile when I think about the black top. Ole folks talked about Princeton with proudness. My great grandmother lived next door to Paul Robeson. My mother says that she would walk pass Einstein’s house and a woman in dark clothes would pass out cookies to kids. As a child I never experienced racism, but I was always told not to wander around Nassau Street.

What a wonderful read.

Jeremy White

8 Years AgoAnd I grew up in Princeton...

And I grew up in Princeton in the '70s. My parents told us to bike down John Street to get to our school (Community Park), but I wasn't wild about it, as there was a particular bunch of kids who would chase me and throw rocks at me. That wasn't fun. If coming home late from school, I'd take the longer route on Witherspoon — less likely to have rocks thrown at me and my bike. Turns out lots of people can be affected by tribalism.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoNot Only in Princeton

The same thing happened to me in a university town in California in the ’70s.

Dean Pannell

8 Years AgoReally — you didn’t realize...

Really - you didn't realize that white people in Princeton didn't have negative feelings toward blacks. I was born in 1961. My brother was born in 1950. He went to elementary school on Nassau Street. He told me that black kids could only take a certain route to school from our downtown neighborhood because the residents would call the police.

My father Henry Pannell, who grew up in Princeton, used to tell us stories about many instances of de facto and outright segregation. They had to sit in the balcony at the Garden Theatre! Your post screams white privilege.

Sherry Kimble Johnson

8 Years AgoMy husband and I, children...

My husband and I, children of a professor and a local businessman, both grew up in Princeton, starting public school in 1947. As far as we knew, black and white children always went to school together. We had black teachers, and a black principal, who we loved and respected. It makes me so sad to think that our black classmates might not have realized that we didn't have the negative feelings that evidently they perceived. I have always attributed my personal "color-blindness" to that fact that I was brought up in a town which, from my point of view, was not segregated or prejudiced. As for the locked big FitzRandolph Gate? We might have wondered why they were locked, but it never occurred to us that it was to keep anyone out. The smaller gates on either side of them were always wide open!

Ellen “Sara” Rosenbaum McCance ’81

8 Years AgoAcross Nassau Street

I very much enjoyed reading “Across Nassau Street” (cover story, April 26). It brought back happy memories of living in the neighborhood across from the University. During my senior year I didn’t want to live on campus. Instead, I stayed in a tumbledown house on Green Street with a group of other students. We were frequently asked by our neighbors to do something about our lawn, a tangle of weeds and tall grass. I regret it now, as I would feel the same if a group of students stayed in my neighborhood and let their garden go to weed in such a disastrous manner.

The house was in a sad condition, and we spent a lot of time fixing the plumbing and trying to patch the plaster. Still, it was a great year and a great place to live. We made many friends in the neighborhood, and often stopped to chat with them when we walked to Conte’s for pizza on a Saturday night.

I think I wore a path between that house and my carrel in Firestone Library. I’ve often wondered if the house continued to be a home for students and whether other people have memories of living there. After reading your article, I had a look at it on Google Earth and it looks just like I remembered it, all those years ago.

Michael Ellis ’59

8 Years AgoAcross Nassau Street

Kudos to PAW for “Across Nassau Street,” perhaps the finest article I remember ever reading in the publication. As an undergraduate student in the late Clueless Fifties, I recall hearing very slightly, perhaps from a professor in a lecture, that there was a “colored” population in Princeton, but no attention was ever paid to it. Nobody was encouraged to go there and no one was told not to — for all intents and purposes, such a thing existed largely in rumor (I certainly sensed, coming from Massachusetts, that Princeton was very much a Southern college, evidenced by so many of its students). I was delighted by the report of the oral-history project and learned a lot from it. And to add to that treasure, the photograph on the cover was a mute but stunning representation of Black Pride. Thank you so much!

Ellen “Sara” Rosenbaum McCance ’81

8 Years AgoLiving Across Nassau Street

Published online July 31, 2017

I very much enjoyed reading your article, “Across Nassau Street” (cover story, April 26). It brought back happy memories of living in the neighborhood across from the University. During my senior year I didn’t want to live on campus. Instead, I stayed in a tumbledown house on Green Street with a group of other students. We were frequently asked by our neighbors to do something about the state of our lawn, which was a tangle of weeds and tall grass. I regret it now, as I would feel the same if a group of students stayed in my neighborhood and let their garden go to weed in such a disastrous manner.

The house was in a sad condition, and we spent a lot of time fixing the plumbing and trying to patch the plaster, which had a habit of falling off the walls. Still, it was a great year and a great place to live. We made many friends in the neighborhood, and often stopped to chat with them when we walked to Conte’s for pizza on a Saturday night.

I think I wore a path between that house and my carrel in Firestone Library, which is probably still there. I’ve often wondered if the house continued to be a home for students and whether other people have memories of living there. After reading your article, I had a look at it on Google Earth, and it looks just like I remembered it, all those years ago.

Michael Ellis ’59

8 Years AgoKudos for Oral-History Report

Published online July 6, 2017

Kudos to PAW for the wonderful article in the April 26 issue, “Across Nassau Street”: perhaps the finest article I remember ever reading in the publication. As an undergraduate student in the late Clueless Fifties, I recall hearing very slightly, perhaps from a professor in a lecture, that there was a “colored” population in Princeton, but no attention was ever paid to it. Nobody was encouraged to go there and no one was told not to – for all intents and purposes, such a thing existed largely in rumor (I certainly sensed, coming from Massachusetts, that Princeton was very much a Southern college, evidenced by so many of its students). I was delighted by the report of the oral-history project and learned a lot from it. And to add to that treasure, the photograph on the cover was a mute but stunning representation of Black Pride. Thank you so much!

Grenville Cuyler ’60

8 Years AgoPhotos ‘Noble and Proud’

Published online July 6, 2017

Reference: “Across Nassau Street” (cover story, April 26): The excellent photos on the Princeton Alumni Weekly cover and of Nancy and Emma Greene are important as we are all, in fact, people of color, by virtue of being human (red blood runs through each one of us). Philip Diggs, the borough’s first black police officer who is shown on the cover, is noble and proud; that is true of Nancy and Emma Greene as well.

Daring of the Princeton Alumni Weekly to highlight the oral-history project generated by author Kathryn Watterson and conducted between 1999 and 2002.

Jeffrey B. Perry ’68

8 Years AgoPreserving Local History

I would like to commend the Princeton Alumni Weekly for its wonderfully informative article on Princeton’s African American community (“Across Nassau Street,” April 26). The article by Deborah Yaffe draws on the work of Kathryn Watterson and three dozen University students who did oral-history interviews between 1999 and 2002 and mentions “dozens of photographic collages” by Romus Broadway.

PAW is pointing the way forward for a much larger project that should be undertaken immediately. Mr. Broadway, an outstanding photographer and lifelong Birch Street resident, has 30,000 negatives taken over 50 years that focus on Princeton’s African American community, the University’s African American students from the early 1960s on, and the University’s multiracial Princeton community workforce. He has a remarkable memory and can name, and provide background for, individuals he has photographed.

Now is the time to approach Mr. Broadway regarding his collection and to encourage a new group of students to utilize and develop their oral-history skills in a project vital to a fuller understanding of the University’s history.

Julie Siestreem

8 Years AgoLook forward to being able...

Look forward to being able to do research in Mr.Romus Broadway's collection once it is included in Princeton's library.

Holt Maness ’69

8 Years AgoExcellent thought...

Excellent thought ... the wealth of detail still available will enrich all of us who benefited from interactions with the Princeton community outside the gates.

Tracy Mott ’68

8 Years AgoI agree with my classmate...

I agree with my classmate Jeff Perry's suggestions. They would add a lot to our knowledge of the history of Princeton and its relations with and the contribution of the African-American community of Princeton.

Paul Hertelendy ’53

8 Years AgoPreserving Local History

“Across Nassau Street,” about the black Princeton downtown, showed areas few of us knew. However, I’d like to point out the valuable role of the Princeton Summer Camp in Blairstown, N.J., where we undergrads made up almost all of the staff of counselors. There the boys/campers I recall were mostly from the underserved black Princeton community. It left an indelible mark in our education about the real world (our class had only two black students going through to University graduation), while adding worlds to their education about the great outdoors, forests, lakes, and related sports. The summer camp later became an independent resource, but in the 1950s, it was an important ingredient offered by the University, to the benefit of both groups.

stevewolock

8 Years Ago‘Across Nassau Street’: Voices of Princeton’s Black Community

“Across Nassau Street” brought back many memories of my years at Princeton.

When I was preparing to leave Wisconsin for Princeton in the fall of 1957, an aunt inquired: “Are there any black students at Princeton?” I told her that I did not know. When I arrived on campus, there were no black seniors. There were also no black juniors. There were two black sophomores. One was a student from Chicago, who was mentioned in PAW not too long ago. Unfortunately, he left at mid-year. The other was a very light-skinned fellow who made it quite clear he did not want to socialize with me. There were two freshmen, me (of course) and another guy who was passing for white.

There were many white students who made it clear to me they thought I did not belong. There wasn’t any physical abuse or outright taunting, but they refused to speak to me or made comments under their breath that they did not approve of me sullying their white school. I soon learned that Princeton was referred to as the northernmost of the Southern schools.

Fortunately, there were several other Wisconsin classmates who remembered me from Badger Boys State, where I had been elected to statewide office, although I was the only minority present. Additionally, there were other classmates who simply did not demonstrate any racial animus.

That first year, there was one black faculty member. One day as I was walking across campus, our paths crossed. He stopped me and said he knew I expected him to invite me to his house for a conversation. Without pausing, he said he was not going to do that and as far as he was concerned, I was on my own. His attitude really cut me. After that, I made a special effort to show him that I belonged.

I found comfort crossing Nassau Street and venturing into the local community. As much as I enjoyed the music from the Chapel organ, I found solace in the First Baptist Church of Princeton, just a few blocks across Nassau on John Street. I recall telling the congregation one Sunday morning that I really appreciated the choir’s versions of the spirituals I had listened to while growing up in Wisconsin. The church members made me feel right at home.

It was through that church I learned of a black barbershop several blocks down on Witherspoon. I went to that barbershop for four years and engaged in free-flowing conversations about what Jackie Robinson had done, what Henry Aaron was doing, and other typical barbershop topics. Through the church, I made contacts that allowed me to poll black Princeton teenagers on race relations for my junior independent work, which was very well received. A young lady who was very interested in my study provided valuable assistance in getting her fellow students to respond to my questionnaire. When my parents traveled to Princeton in June 1961 for Commencement Week, they stayed in her parents’ home on Maclean Street.

Because of these experiences, it was 20 years before I returned for a reunion. Experiences during the reunions I have attended and Princeton football games in San Diego have taken the edge off many of the experiences mentioned above. It is more common now for classmates to approach me, recall that they didn’t speak to me much while we were undergraduates, and then apologize for that treatment of me. They have grown, and that makes my memories so much easier to bear.

Princeton, as expected, was challenging academically. Socially, there were many problems. Emotionally, it was a devastating experience. Time heals all wounds, however. The California license plate on my car reads, simply, “61Tiger.”

Philip L. Johnson ’61

Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif.

My years at Princeton began in the fall of 1956. From the beginning, needing to know more about the civil-rights movement, I began my exploration. When bicker occurred, I did not participate. I did not want “the Street”; I did not want the clubs; I did not want the elitism that all of that represented, even though my dad was head of Tiger Inn when he graduated in 1927. He wanted me to participate; I refused, because I had discovered an entirely different life down Witherspoon Street.

[node:field-image-collection:1:render]Bennett Griggs’ restaurant was my home, my eating place, my community, for me and my friends who felt as I did. The civil-rights era was beckoning; he and his extraordinary family invited me/us into the neighborhood. In upperclass years, I was spending so much time out of Princeton — in New York City, running a summer-stock company — that the Street was irrelevant. But learning about the black community and its culture would form my core forever. This perspective, the gift of the community to the University students, should be included in a follow-up to that original story.

Had not Bennett Griggs and his family guided and instructed me in the trenches of civil rights while I was at Princeton, I would not have been sufficiently transformed to be able to become a producer of the movie Woodstock in 1969, less than a decade out of college. We won the Academy Award in 1971.

Dale Bell ’60

Santa Monica, Calif.

“Across Nassau Street” brought back memories of my senior year. Because of unpleasant experiences during the troubled 1958 bicker, when it came time for me to participate in the 1959 bicker, I declined. However, I was told that I could not remain a member of the club if I didn’t help recruit the next class, so I and two of my roommates resigned. Breakfast and lunch were easy; we had a refrigerator in the room, and I generally had cereal in the morning and made soup or a sandwich for lunch.

Dinner was more of a problem, particularly financially. We solved that by eating at Griggs’ restaurant on Witherspoon Street at least five nights a week, usually a large hamburger served on white bread, with some home fries, generally brought to our table by Mr. Griggs himself. On our last night there, he brought us a steak, on the house. My recollection is the meal cost a little over a dollar each evening. That allowed us to splurge one night every week or two at one of the smorgasbords at either the Nassau Inn or the old Princeton Inn, with all the roast beef you could eat for $2.50 or $3.50, respectively.

Richard J. Lederman ’60

Shaker Heights, Ohio

My father, Warrant Officer Herman Archer, attached to the Princeton ROTC, unmarried at the time, living in the barracks just north of the ROTC stables, desegregated Griggs’ restaurant, at the corner of Witherspoon and Hulfish (now Griggs Corner). That would be before 1928, when he married. They were good friends and met often until we left for the Philippines in 1937. In 1945, when my father returned from a Japanese prison camp, Mr. Griggs invited our family to a grand steak banquet at his restaurant. He was a grand man.

Herman Archer Jr. ’53

Kingwood, Texas

Web Exclusive: More ‘Across Nassau Street’ Letters

“Across Nassau Street,” about the black Princeton downtown, showed areas few of us knew. However, I’d like to point out the valuable role of the Princeton Summer Camp in Blairstown, N.J., where we undergrads made up almost all of the staff of counselors. There the boys/campers I recall were mostly from the underserved black Princeton community. It left an indelible mark in our education about the real world (our class had only two black students going through to University graduation!), while adding worlds to their education about the great outdoors, forests, lakes, and related sports. The summer camp later became an independent resource, but in the 1950s, it was an important ingredient offered by the University, to the benefit of both groups.

Paul Hertelendy ’53

Berkeley, Calif.

Kudos to PAW for the wonderful article in the April 26 issue, “Across Nassau Street”: perhaps the finest article I remember ever reading in the publication. As an undergraduate student in the late Clueless Fifties, I recall hearing very slightly, perhaps from a professor in a lecture, that there was a “colored" population in Princeton, but no attention was ever paid to it. Nobody was encouraged to go there and no one was told not to – for all intents and purposes, such a thing existed largely in rumor (I certainly sensed, coming from Massachusetts, that Princeton was very much a Southern college, evidenced by so many of its students). I was delighted by the report of the oral-history project and learned a lot from it. And to add to that treasure, the photograph on the cover was a mute but stunning representation of Black Pride. Thank you so much!

Michael Ellis ’59

Hilliard, Ohio

Reference: “Across Nassau Street”: The excellent photo on the Princeton Alumni Weekly cover and of Nancy and Emma Greene on page 25 are important as we are all, in fact, people of color, by virtue of being human (red blood runs through each one of us). Philip Diggs, the borough’s first black police officer who is shown on the cover, is noble and proud; that is true of Nancy and Emma Greene as well.

Daring of the Princeton Alumni Weekly to highlight the oral-history project generated by author Kathryn Watterson and conducted between 1999 and 2002.

Grenville Cuyler ’60

New York, N.Y.