Months before the first women undergraduates arrived at Princeton, changes were underway within the administration. In 1969, the University had allowed women to apply, but it could not admit these candidates without approval from the board of trustees. Faced with this waiting game, Admission Director John T. Osander ’57 hired Carol Thompson, who had worked in admissions at Radcliffe before relocating to Princeton. Along with two other women who were part-time employees, Thompson was to conduct the initial evaluation of all female applicants.

When women were officially admitted, other administrative offices added more women to their ranks. The most prominent was the appointment of Halcyone H. Bohen as assistant dean of students. Bohen, whose arrival at Princeton was later described by The New York Times as part of an effort to “smooth the transition to coeducation,” was the first female dean in University history.

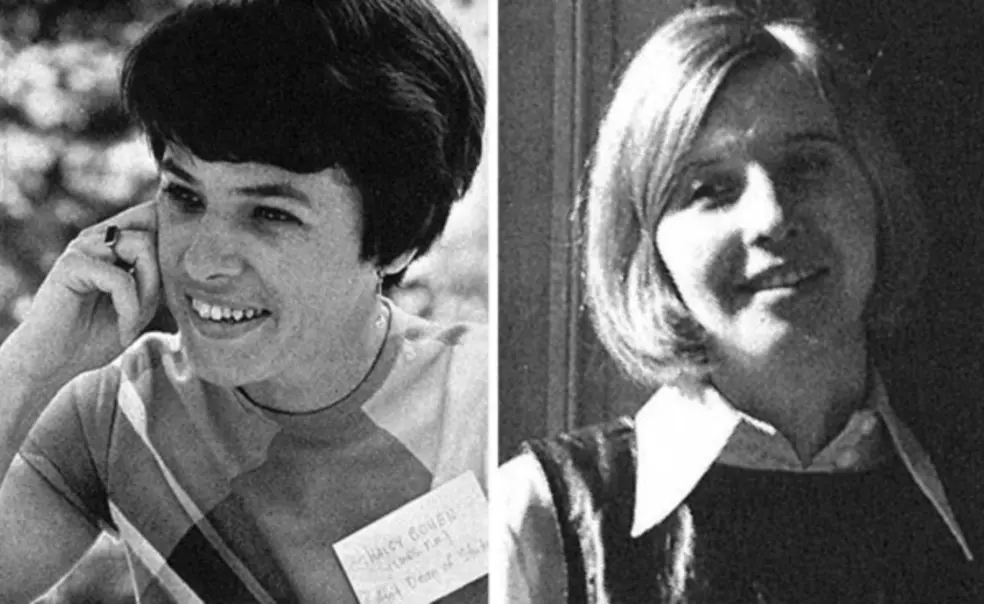

PAW highlighted the new hires with short profiles of Thompson and Bohen in the fall of 1969 (stories that illustrate the magazine, like the University, just beginning to navigate the new world of coeducation). Both worked with a range of students, “in line with the University policy decision not to regard men and women as separate campus groups,” as PAW’s columnist phrased it. Thompson became a regional admission officer, handling applicants from New York and New Jersey, while Bohen’s work covered various student-life issues. Their stories remind current readers of the many faculty and staff members whose belief in the promise of coeducation would facilitate historic changes on campus.

Princeton Portrait: Halcyone H. Bohen

(From the Sept. 30, 1969, issue of PAW)

Her office in West College conceals a warm, hectic smile. Through a crack in the door, colors splash from a wall-sized mural of orange, blue, and yellow flowers. Left and right are plastered the bright, bold brush strokes of children’s art — the collected works of her three small daughters. Halcy emerges from her otherwise sparse surroundings. Her dress matches her walls, gay and colorful; the NBC News cameramen waiting outside will have plenty of color for the peacock.

Halcyone H. Bohen, 31, Princeton’s newest Assistant Dean of Students, has met a lot of people in a week. More often out than in, she divides her day between greetings at Pyne Hall, meetings around campus, and briefings in her office. Reporters pursue her during most working hours. To escape, she takes her work home, holding informal get-togethers with new students.

As she sees it, people are her full-time job. Students, both men and women, parents, even reporters get her easy, confident attention.

How does one become the first woman dean in Princeton history? Mrs. Bohen tells it this way: “I was in Princeton for a going-away party for Dean Bernstein [Marver H. Bernstein *48, former Dean of the Woodrow Wilson School], and someone mentioned this job opening ... .” Still, she brings an impressive record to her new chores. Armed with a Master of Arts degree from Radcliffe in social studies teaching, she first came to Princeton in 1962 with her graduate-student husband, Frederick M. Bohen *64, and began writing history, government, and social studies questions for the college boards. At the same time, she found an editorial outlet for her thoughts by persuading the Princeton Packet to publish a weekly column of “analytical articles” on topics ranging from the part-time employment of women to the Princeton appearance of Malcolm X. “I always wanted to be a reporter,” she recalls.

After moving away from Princeton in 1966, Mrs. Bohen taught an afterschool art program for children in Washington, D.C., and conducted a seminar in urban problems for rookie policemen in New York. Her return this month finds her uninvolved in the numerous important developments at Princeton over the past three years. She is as new as her position; and she speaks cautiously, sometimes vaguely, always optimistically.

In line with the University policy decision not to regard men and women as separate campus groups, Mrs. Bohen will, happily, deal with both. She can see the coming year as one of getting acquainted, and getting involved, with students — she has yet to gauge the extent of coming alumni reaction to herself and her girls. Fortunately, first-week problems of involvement were simple, if annoying: new locks hadn’t arrived at Pyne, men made too much noise in the campus’ most popular courtyard, reporters pestered for more news of June Fletcher ’73, Miss Bikini, U.S.A. But coeducation, she’s convinced, is the best possible thing for Princeton.

And for Smith, her alma mater?

“If they want to do it, sure.”

Princeton Portrait: Carol Thompson

(From the Nov. 11, 1969, issue of PAW)

Traditionally, admission office personnel smile a lot. Even when prospects happen to look bleak for a university, these energetic workers can be counted on to project a sanguine image of the campus in an effort to lure the best students. The smiles around the Princeton admission office these days are not forced, however, but are genuine reactions to a phenomenon unprecedented in the University’s history. Preliminary applications for the Class of 1974 are up 87% compared to the same time last year. Even without considering women’s applications, the figure is still a surprising 43% above last year.

One of the people directly involved with this boom is Mrs. Carol Thompson, who joined the admission staff only last January to work with the first women’s applications. Wife of politics assistant professor Dennis Thompson, the pretty, blonde mother of two now works with both male and female applicants from New York and New Jersey.

“It’s pretty clear that coeducation has a lot to do with the increase in applications,” she explains, “but it’s the implications we’re most concerned with. We’re now faced with possibilities for diversity or homogeneity that we haven’t had before. We’re asking, ‘What makes a good, balanced class?’ and we don’t know.” Thus a situation that at first might seem to be fraught with nothing but happiness for the admission office contains some highly complex problems as well.

“Many more applicants than before, especially girls who could definitely handle a Princeton education, will have to be turned down,” Mrs. Thompson contends. “There will have to be some tightening in different areas, perhaps athletics, but we’re not really sure which.”

Although she has not yet seen any of the applications, Mrs. Thompson notes that “the schools assure us we are getting their very top applicants. We’re competing primarily with Harvard and Yale, both for men and women.” A former Senior Resident at Radcliffe and an interviewer in the Radcliffe admission office, she characterizes the girls she has interviewed this year as “very similar” to those she saw in Cambridge.

A situation of parity or near-parity among the schools will lead, she hopes, to a less, rather than a more, competitive atmosphere. Admission policy should aim for a “cooperative effort among colleges, promoting some kind of inter-college placement. I’d like to open up admissions, to tell a student how he can improve his application even if he isn’t accepted here.”

As to what Princeton is seeking in applicants, Mrs. Thompson stressed that the same criteria apply to male and female candidates, except that maturity is perhaps more important for the girls: “We’re looking for girls who can make the most of a lack of structure.”

Although she admits that many alumni feel the role of the Alumni Schools Committees has been diminished from evaluating individuals to evaluating schools, Mrs. Thompson points out that “we’re really asking for more information. We’re counting on them just as much.” After less than a full year on the job, the 1962 Michigan graduate is sure she wants to stay with admission work permanently. “You get to see the best side of people all the time,” she smiles. — By Brant Davis ’70

No responses yet