After 46 Years, Men’s Track and Field Mentor Fred Samara Retires

“Coaching was a 24/7/365 type of thing for me,” Samara said

Collegiate track and field coaches serve on a relentless treadmill of responsibility: cross country in the fall; indoor track in the winter; outdoor track in the spring; and recruiting new talent in the summer — then repeat. For many, it can be a grind that becomes intolerable. Not so for Princeton men’s track and field mentor Fred Samara, who retired in late June after 46 years at the University, all but two of them as a head coach.

“Coaching was a 24/7/365 type of thing for me,” Samara said. “Even late at night I would call guys on the team, view films, address email and texts. Up until four years ago, I was coaching all the jumps, all the throws, all the multis [decathlon and heptathlon], plus sticking my nose in when I spotted somebody in, say, the sprints, I would go over and say something.” After a pause, he laughs: “Now when I look back on it, I don’t know how I did all that.”

Jason Vigilante, the men’s cross country coach since 2012, will succeed Samara, the University announced in August.

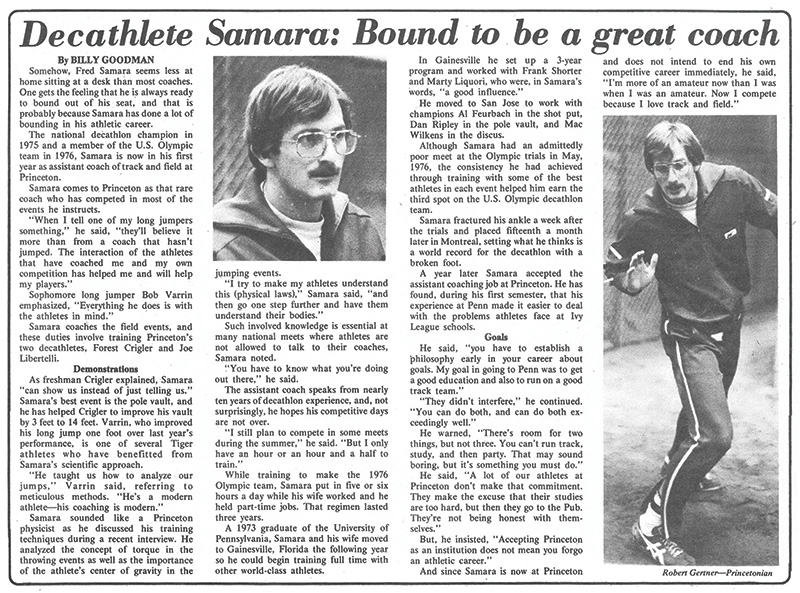

Samara’s track and field journey is a love affair that began early and blossomed while he competed as an athlete at Penn, earning All-America status in the sprints, long jump, pole vault, and decathlon. After college, Samara went on to gain a top-10 world ranking in the decathlon and compete in Montreal on the 1976 U.S. Olympic team.

When he took on coaching responsibilities at Princeton in 1977, a new and sparkling era of track and field began. Under Samara, the Tigers won 51 Heptagonal team titles and 502 individual championships; nine athletes captured NCAA championships; and six made Olympic appearances. Samara coached more athletes and won more championships than any other coach in Princeton history.

There are several keys to Samara’s unmatched success, according to those who either coached with him or competed for him. Upon his arrival on campus, Samara brought instant credibility. The best athletes aren’t always the best coaches, but Samara was. Athletes quickly learned that Samara, a world-class multi-athlete, was well equipped to teach all 10 of the decathlon events and could impart helpful training and performance tips as well.

“Fred is one of the most gifted, technical coaches I’ve ever worked with,” said Justin Frick ’10, a Tiger high jumper who later spent four years on Samara’s staff as a volunteer coach. “Across a wide variety of events he was able to be just as facile talking with a pole vaulter or a high jumper as he was with a shot putter or a discus thrower.

“Beyond the obvious athletic piece, Fred did a great job of instilling in his athletes a commitment to excellence — and something beyond just athletics,” Frick added. “He put in a lot of time and effort understanding his athletes and promoting their adherence to commitment off the track, just as he expected on the track. The reason so many of his athletes have been successful not only at Princeton, but also after Princeton, is because of that commitment.”

With the Power Five universities attracting the vast majority of blue-chip track and field athletes, Samara developed a keen sense of identifying eager high schoolers with underdeveloped potential. Mike Charles ’88, a shot put and discus specialist, learned upon his arrival that the Tigers already had two sensational sophomores in his events, and Samara recommended switching to the hammer throw and the 35-pound weight — two implements Charles had never thrown. “Fred gave me the attention that I needed while I was learning this new event,” Charles said. “Fred gave me the same attention that he gave to everyone. He had the boundless ability to be everywhere.” By his junior year, Charles was scoring points for the Tigers at the Ivy League Heptagonal Championships.

Decades later, Charles’ son, Mitchel Charles ’18, had a similar experience. “My junior year in high school was fine, but not recruiting-worthy,” he said. Samara called anyway, and the 6-foot-5, 216-pound Mitchel enrolled at Princeton. Samara took him under his wing, helping him add 60 pounds during his freshman year. Mitchel laughed recalling Samara’s advice: “You’re working out so much, it’s all going to be muscle. Don’t worry. Keep eating!”

The younger Charles outpaced his father’s impressive development as a thrower, earning four Heps championships in the shot put. “Coach communicates what the plan would be in a way that inspires trust with the athlete,” he said. “If you listen to him, he will get you where you want to go.”

When it came to tutoring a budding athlete, Samara was a stickler for focus during practice and precise execution. “The common phrase is, ‘Practice makes perfect.’ But Coach Samara preferred to say, ‘Perfect practice makes perfect,’” said long jump and triple jump specialist Nathan “Nic” Crumpton ’08.

Crumpton, who would later become the first Princetonian to compete in both the summer and winter Olympics, remembers a special moment he shared with his coach at the indoor Heps meet in his senior year. He was coming off an injury, and on his final jump, he shot up the leaderboard to finish in second place. “Coach Samara, after biting his nails and coaching me through injury, rushed up and gave me this great big hug, this unspoken bond that I had come through and earned some precious points for the team,” he said. “No words were spoken — just his big, enthusiastic hug. … I had reached my potential, fought through my injury, and delivered it when it counted. I could see that he took a lot of pride in that as well.”

Samara delivered for Princeton, bringing together five decades of athletes, showcasing the importance of steadfast commitment and precise preparation, and celebrating stellar performances in the moment. And even with his unparalleled success, he relished each new competition.

“Fred may be one of the most competitive people I’ve ever met,” said Jay Diamond ’86, a long jumper and recent president of the Friends of Princeton Track. “He wanted to win Heps badly every year. … As he was winning — and he won a lot — he couldn’t get enough of it, and he wanted more of it.”

No responses yet