An American appetite

Food has always been the center of my world. Growing up in New York City in the ’80s, I was raised on my French mother’s home cooking, coming of age with gorgeously gooey gratins, an abiding affinity for duck fat, and an admitted sense of bread snobbery. On my dad’s side, I was a fifth-generation New Yorker, and that meant, as many Manhattanites will attest, restaurants. We went out constantly, and were never on the same continent two nights in a row. Volcanic vindaloos on Saturday, honey-gushing baklava on Tuesday, and crispy schnitzels on Thursday. Eating, for me, was always an otherworldly, or at least an across-the-worldly, experience.

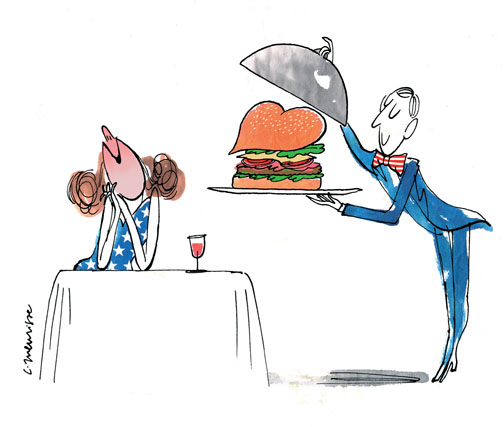

American food, on the other hand, was kids’ food. Chicken fingers. Cheeseburgers. Yeah, I ate it occasionally and loved it, but my mother, as many French mothers do, prided herself on my gastronomic inquisitiveness, and I was more likely to be seen cracking a lobster than nibbling a hot dog.

It was only when I went to Europe to attend graduate school at Oxford that I truly began to appreciate American cuisine. It was 2007 — not the best time for Americans abroad. My new neighbors didn’t bother to hide their disdain toward me, the new Yank. I had never had to defend who I was before, and I was caught somewhere between rebellious pride and a shameful desire to tuck away my American identity so that it would be safe for later.

One night, feeling homesick and lonely, I dug into the suitcase under my bed and pulled out a special treasure I had reserved for just such a moment: a box of Kraft macaroni and cheese, purchased for a precious £5 at Partridges in London. I tiptoed off to the little dormitory kitchen, hoping no one would catch me and judge me in this ultimate moment of Americanness. I tore open the little blue box, and cascaded the noodles into a pot of boiling water. Yes, I added some grated extra-mature English cheddar — I am a food writer, after all — but then I sat down on my bed with my bowl of lurid orange pasta clutched tenderly against my chest, and I gulped it down, feeling each bite somehow restore in me a piece of who I was, of where I was from, of what I really wanted.

I’m not sure where the general dismissal of American cuisine comes from — or why the idea that we don’t have an American cuisine ever took root. In cooking school in Paris, during one demonstration, I gasped at my chef’s liberal use of butter. “Mais non!” he chided me. “Ce n’est pas du tout aussi mauvais que ton Coca-Cola!” It’s not nearly as bad as your Coke. It was just another one of the outlandish jibes of culinary bigotry I came to regard as ridiculous. He can think American food is just Coca-Cola all he wants, but I know better.

Because, over the last five years in Oxford and London, I have established a very clear definition of American cuisine. Because I miss it. I crave it. I go to sleep thinking about it, and I wake up dreaming about it. Like a smoker who’s forced to quit because he’s run out of cigarettes, I’ve had to go cold turkey.

Mmm. Cold turkey. I wonder where I can get that here.

The salty, juicy snap of a half-sour pickle. Blueberry pie, room temperature, no ice cream. Corn on the cob, in any iteration. Corn muffins, toasted, with sweet butter. Sweet potatoes, fried. Turkey, just generally. Pulled-pork sandwiches with cool coleslaw. Tea that’s iced. A bagel my grandfather would have called a bagel. Lobster, plain and proper. Bacon that’s smoked and crispy and right. Gosh, how great are BLTs? Jumbo shrimp cocktail. Iceberg wedges with blue-cheese dressing. Good, aged steak; not overcooked. Pumpkin pie.

There are not words to describe how I miss these foods! This menu seems disparate, even quotidian. But the unifying factors are simplicity, honesty, and integrity. Real American food was local and seasonal before it was cool to be local and seasonal. Nothing on that list has more than a handful of ingredients. American food takes the best of what’s around, and makes it just a bit better — whether it’s a New England clambake or shrimp and grits in the South. No muss, no fuss; just real, clear, honest food, done with our American ingenuity and determination for perfection.

And that’s what I miss most.

Over the last five years, I’ve made my mark writing about French food, and I’m about to marry a British man. Some may say I’ve gone native. Not so. Gone are the days of shame. I now openly proclaim at the office to friends and co-workers who smile with good humor that America has the best food in the world. I tug them along to try the new Tex-Mex Chipotle knockoff burrito place in Hammersmith. I sit them down at a table at Honest Burgers and order them gourmet burgers and a flat lemonade float. And suddenly, recently, standing in line at MEATliquor, a trendy American restaurant in London specializing in gourmet burgers and onion rings, salivating over the increasingly imminent fried pickles and Bourbon, I smiled at the slow, dawning realization that America has a whole new export: food.

No, it’s not Kraft and Coca-Cola (though I do praise them for being, in moderation, delicious cultural ambassadors). Instead, it’s real American food, done the American way. MEATliquor plates up flat-top cheeseburgers in the In-N-Out or Shake Shack style, but in a fancy Marylebone outpost with a line snaking around the corner from 7 o’clock. At Burger and Lobster, a tiny restaurant chain in London, you can order only the eponymous burger or lobster, done right with drawn butter, or a brioche roll. Or my favorite addition, which I’ve yet to try: Mishkin’s, a self-proclaimed “kind-of Jewish deli with cocktails,” which couples the Reuben with schmaltzed radishes, and cream soda with Chablis. These restaurants are either imitating or re-creating American classics in a modern American way — casual but excellent, simple food with tradition, and no reservations. And last night on the British food channel, there was a three-hour American lineup, with British culinary celebrities doing their requisite tours of the States. I sat back in proud, stomach-rumbling bliss, as Jamie Oliver served collard greens and grits.

One thing I’ve learned from the French side of my family is that pride in your food is pride in who you are as a nation. I’m proud that we’re no longer hiding our light under a bushel. American food is — and here’s a word I can use only with my fellow Americans, so I employ it with added vim — awesome. The sweet-tart burst of a cranberry. The juicy char of corn grilled in its husk. The corn-crackle crunch of a fried green tomato. The honesty of a New York seared steak. Compared to the French classics on which I was raised, or to the exotic reveries to which I escaped in my restaurant days, there’s not much there. But it is so us, making use of what we have, adding ingenuity, dedication, and resourcefulness, and making it the best there is. You can taste our character in our food.

I’ll eat to that.

Kerry Saretsky ’05 is a publishing strategist and food writer. She lives in London, and her blog French Revolution can be found at www.frenchrevolutionfood.com.

No responses yet