Annalyn Swan ’73 and Mark Stevens ’73 Illuminate a Dark Artist

A husband-and-wife team has published a biography of artist Francis Bacon

“Annalyn is a bloodhound,” says Mark Stevens ’73, of his wife, classmate, and co-author, Annalyn Swan ’73. “Do you mind being called a bloodhound?”

Swan confirms over Zoom that she does not.

“She’s a fabulously energetic researcher, and I’m a lazy gadabout, really,” explains Stevens, a longtime art critic whose work Swan used to oversee as senior arts editor at Newsweek. “I mean not entirely — I can be provoked, but I don’t have the same appetite that she does” for research.

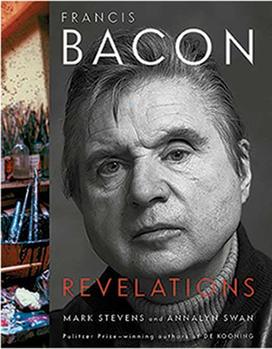

That appetite — as well as flashes of what Swan calls her husband’s “very witty and wry” prose style — informs their second biographical collaboration, Francis Bacon: Revelations (Knopf), published in March. The Anglo-Irish figurative painter, who died in 1992 at 82, stunned the mid-20th-century art world with his grotesque images and flamboyant lifestyle. A decade in the making, the new biography offers a more nuanced portrait, including Bacon’s early foray into modernist design, his unabating self-criticism, and his frequent kindnesses to friends, family, and lovers.

The couple’s first project, de Kooning: An American Master (Knopf, 2004), on the Dutch American abstract expressionist painter, won a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Los Angeles Times Book Award for Biography. Francis Bacon has received mostly rapturous reviews. Charles Arrowsmith’s critique in The Washington Post described it as “bejeweled in sensuous detail.” The New Yorker’s Joan Acocella wrote that the biography was “warmed by the writers’ clear affection for Bacon.” Parul Sehgal of The New York Times praised its “ambition and scope,” but took issue with the authors’ handling of Bacon’s lurid private life as “prim and almost anthropological.”

“It’s because people really don’t want to see him in the round,” Stevens says in response to the Sehgal comment. Along with Bacon’s well-known predilection for sadomasochistic gay sex, Stevens says, “he had these desires for friendship, for domesticity, for some sustained relationship.”

Bacon was a descendant and namesake of the Enlightenment philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon (1561–1626). A gambler and a drinker, he partied relentlessly through London by night and painted faithfully each morning — only to destroy many of his canvases. Francis Bacon instances his petty cruelties, but also his elegant manners, charm, and generosity.

Illustrated with Bacon’s images of disemboweled carcasses and screaming popes, as well as his portraits of male lovers and female friends, the biography traces the artist’s career arc as he careened from destitution to celebrity. It catalogs his turbulent friendships with artists such as Graham Sutherland and Lucian Freud and romances that could be transactional or violent or both. The greatest of Bacon’s loves, the test pilot and pianist Peter Lacy, once threw him out a window. “It’s a bizarre relationship,” Stevens says, “but, for both men, it was very important — and the violence was part of it.”

Biography, Stevens says, “has its own imperatives. It’s portraiture.” Swan, who teaches biography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the Middlebury Bread Loaf School of English, stresses the need to infuse the narrative arc with drama. The couple refashion each other’s prose “in endless iterations,” she says, bringing “a novelistic sensibility to bear on the facts.” They aim for a style, her husband says, that is “alive and epigrammatic, but also transparent, so that you see through the words to the subject, and you’re not being distracted always by the writing itself.”

Swan and Stevens met at The Daily Princetonian, where Swan was the newspaper’s first female editor-in-chief and Stevens the paper’s chairman. An English major, Swan also took art history courses. Stevens, the son of the artist Polly Kraft, concentrated in the then-Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, but was drawn to English and “art-tinged history.” Both earned master’s degrees (he in cultural history, she in English literature) at King’s College, Cambridge, where she was a Marshall Scholar.

The couple refashion each other’s prose “in endless iterations,” Swan says, bringing “a novelistic sensibility to bear on the facts.”

They were married, in 1977, in the Princeton University Chapel. Stevens was an art critic at Newsweek, The New Republic, and New York Magazine. Swan became the classical music critic at Newsweek’s chief competitor, Time, before moving to Newsweek. In the late 1980s, she was editor-in-chief of the women’s magazine Savvy.

When the couple were given the opportunity to write the de Kooning biography, the artist’s reputation was “in some eclipse,” which Stevens says made him intriguing. So, too, did his immigrant background, which gave him “a larger emblematic importance for American culture,” Stevens says. Stevens and Swan took a house in Sag Harbor, Long Island, to conduct interviews with members of de Kooning’s artistic circle living nearby. That immersion “created a template for how we would do research,” Stevens says. The book also established their storytelling approach: “making the art essential to the story we were telling, but also not trying to reduce the life to the art or the art to the life.”

Even after their success with de Kooning, Stevens was ambivalent about a second biography. But Swan says she was “captured by the process,” and pushed for an encore. Then the Bacon estate approached them to write the first comprehensive biography of the artist.

Stevens found the prospect enticing because Bacon, reacting to the genocidal violence of World War II, “sets the dark edge of art in the 20th century. He is arguably the darkest artist, and he’s responding to a very dark century. Also, he developed this existentially drenched, somewhat corny persona that is very dramatic and important — a kind of Wildean persona for our time. And he was a homosexual before gay liberation. That’s interesting, too.”

Swan saw the research possibilities. No prior biographer had visited Ireland to investigate Bacon’s childhood terrain. “And it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that the Anglo-Irish background was incredibly powerful in shaping his sensibility,” she says. An asthmatic in a culture that prized toughness, Bacon had a brutal, violent upbringing and little formal schooling. The New York-based authors also visited England, France, Tangier, Spain, and Italy, places Bacon had lived or frequented, to mine archives, conduct interviews, and scout out his environs.

Their thoroughness affords a rare intimacy. Two of Peter Lacy’s nephews helped transform Lacy from caricature to character, and close associates of Lucian Freud attested to both the intensity and the demise of his friendship with Bacon. The authors communicated through intermediaries with José Capelo, the “elegant young Spaniard” (per the biography) who was Bacon’s last romantic interest and has always declined to talk to journalists. “It’s safe to say that José would be comfortable with everything in our book,” Swan says.

Whatever Stevens’ doubts about Bacon’s art — “a lot is mediocre,” he says — he became fascinated by the project of unraveling his personality. “He was a very complicated man who hid behind a rather simple persona,” he says.

The title references the authors’ own discoveries and the “revelatory aspirations” of Bacon’s art, including its religious connotations, Stevens says. He adds: “Most important of all is that he was interested in flinging open closet doors — not just [to] homosexuality, but all the doors of the Western tradition that conceal uncomfortable truths.”

Bacon’s sexuality is manifest in his depictions of various male lovers, but also in his concern with “absolute power and powerlessness in a larger cultural way,” Stevens says. Yet it is too limiting, Swan adds, to say that “his vision was brutal and tough and violent and masochistic.” Stevens points to two later self-portraits: “Those are not violent images. And they show two very different states of being, each of them quite remarkable: one of them quite lovely, strict and melancholy all at the same time, and the other, this aging queen, who’s just all powder and rouge.”

The authors wrestled with the question: “How far do you step in to judge your subject?” Their answer was, not far. “I really want to present the situation as truthfully and as amply as possible — and then leave the reader to react,” Stevens says.

No responses yet