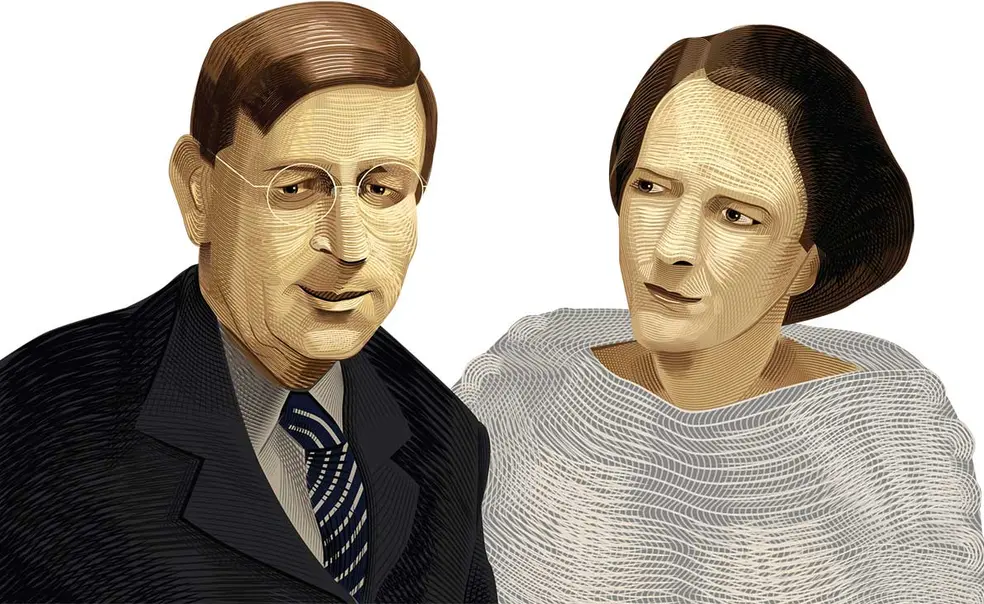

Anthropologists Helen and Robert Lynd 1914 Investigated Middle America

Princeton Portrait: Robert Lynd 1914 (1892–1970)

What is more mystic and uncanny than an ordinary city in Middle America? When Robert Staughton Lynd 1914 and his wife, Helen Lynd, set out in 1923 to investigate an American city using the same methods that anthropologists had applied to tribes in distant parts of the globe, they found a world of secrets and magic. The locals practiced humble sorcery, which they passed down through generations as folk wisdom: “certain persons ‘blew the fire out of a burn,’ arrested hemorrhage or cured erysipelas [infections] by uttering mysterious charms.” They sat coolly at church, then burned hot at camp meetings where preachers spoke with leaping tongues of flame. In 1896, when oil drills hit “a foul odor and a roaring sound deep in the bowels of the earth,” rumors flew through the streets that the drills “had invaded ‘his Satanic Majesty’s domain.’” The drills had hit natural gas, which became the basis of the city’s prosperity.

The city was Muncie, Indiana, population 36,524, but the Lynds called it “Middletown” when they published their study in 1929. Their book became a classic, marking an emerging American sociology when Middle America, as a key idea of the American Century, was also just emerging.

In their study, the Lynds explored the relationship between old social rituals and the modern industrial economy of the “gasopolis.” Teens sought details about the facts of life from magazines like Live Story and True Story, which managed to be both smutty and moralistic, and which readers withdrew from the library in such quick sequence that new issues fell to pieces. (Between 3,500 and 4,000 issues of “sex adventure” magazines like these circulated each month among Middletown homes.) People held onto old cures, such as weaning babes under certain signs of the zodiac or making children climb through hollow trees to make them taller.

The city was Muncie, Indiana, population 36,524, but the Lynds called it “Middletown” when they published their study in 1929.

The study made Middletown a symbol of Middle America. But the very process of seeking in the city an image of the nation wound up distorting the nation’s self-image. The Lynds made the city’s population seem whiter and more homogeneous than it really was, portraying a statistical archetype that didn’t exist. The media distorted the study’s findings still further by leaving out anything — the curses and prophecies and pulp sex fantasies — that wouldn’t have fit in a painting by Norman Rockwell.

After graduating from Princeton, where he received academic honors, Robert Lynd worked for a time in publishing and then earned degrees at the Union Theological Seminary and Columbia University. Robert taught at Columbia for some 30 years; Helen, who also received a Ph.D. at Columbia, taught at Vassar and Sarah Lawrence. In 1938, they published a follow-up study of Middletown.

A year later, Robert wrote an article for the Alumni Weekly, titled “If I Were at Princeton,” that encouraged Princeton students to remember — as a sociologist must — that ordinariness is an illusion, and that we must not mistake culture for nature. “If I were entering Princeton today,” he wrote, “I should say to myself: Here is an artificial environment — a wealthy university dominating a wealthy little residential town ... . There tends to be a marked ‘class’ bias in the Princeton environment, and I shall be unconsciously molded by the fact that Negroes are not admitted, it tends to be a particularly difficult college for the self-made Jew, and persons from other less-favored social and economic backgrounds are probably not so prevalent in the student body.” The rich ordinariness of Princeton — students sleeping on couches in Firestone, carillon notes floating over treetops turning gold, tan, and red — neglects other rich worlds that Princetonians must seek out, he argued: “I must brace myself against the Princeton environment ... I shall try to cultivate contacts in New York that will demand of me: What am I missing?”

No responses yet