Bill Bradley ’65, Butch van Breda Kolff ’45, and the Rise of Princeton Basketball

How a superstar and coach, bonded in their understanding of how the game should be played, set the standard for decades to come

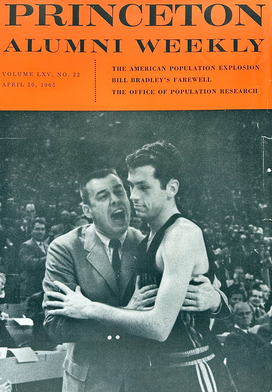

This season marks the 60th anniversary of Princeton men’s basketball’s first and only trip to the Final Four. Led by Bill Bradley ’65 and coached by Willem Hendrik “Butch” van Breda Kolff ’45, those Tigers launched the team to national prominence and created expectations that the program has strived to live up to ever since.

As a high school senior in 1965, I followed the exploits of the Bradley-led Tigers with rapt attention. Here was a university with the academic excellence to keep my parents happy and a basketball program that could compete with the best teams in the country. It made my college choice easy. Long before Gatorade came up with the advertising slogan “Be like Mike,” I wanted to “Be like Bill.”

While I missed out on playing with Bradley, I did play on van Breda Kolff’s last Princeton team during the 1966-67 season, when the Tigers were again one of the top teams in the country. As an 18-year-old sophomore, I felt like a pledge to a special fraternity, playing sparingly and mostly watching the games from the end of the bench. But my front row seat gave me a close-up view of a unique style of basketball, where the ball moved constantly from one player to another and it didn’t seem to matter who took the shot. Van Breda Kolff’s early teams were highly dependent on Bradley, the superstar, but he also knew how to build an ensemble.

In the 61 seasons since Bradley and van Breda Kolff first joined forces in the fall of 1962, Princeton has won 25 Ivy League championships and more than 65% of its games. Along the way, the Tigers built a reputation as the Cinderella team of the NCAA Tournament, after numerous upsets or near upsets over much higher-ranked teams, and won a National Invitation Tournament championship.

Had it not been for the fortuitous pairing of Bradley and van Breda Kolff, though, Princeton’s basketball trajectory would likely have been very different.

In the spring of 1961, after a spectacular career at Crystal City (Missouri) High School, Bradley accepted a scholarship to Duke, a basketball powerhouse. Meanwhile, van Breda Kolff had just coached Hofstra to its third straight 20-win season. It seemed unlikely that the paths of the two men would ever cross.

On a trip to Europe after high school graduation, Bradley visited Oxford on a beautiful summer day and fell in love with the campus. He began to envision one day becoming a Rhodes scholar, and when he learned that Princeton had produced more Rhodes scholars than any other college, his interest in the school, which he had visited twice, was rekindled.

Back home later that summer, Bradley broke his foot playing baseball. While recovering, he thought about where he would choose to go to college if he weren’t an athlete. A few days later, he showed up unannounced on the Princeton campus.

Van Breda Kolff found his way to Princeton under less sunny circumstances, landing the coaching job after the Tigers’ former mentor Franklin C. “Cappy” Cappon died of a heart attack in the fall of 1961. (It was Bradley, who had stayed late at the gym practicing on his own, who discovered Cappon dead on the shower room floor.)

The three years that Bradley and van Breda Kolff would spend together set the tone for Princeton’s basketball program, though it would be hard to find two men who approached life more differently.

Bradley was a serious young man, who had methodically perfected his basketball skills with a daily regimen that helped him become one of the most sought-after high school players in the nation. Everything in his life was planned and programmed to set him on a path to success, in both basketball and life.

Van Breda Kolff, on the other hand, was a gregarious and charismatic charmer, always the life of the party. He’d played for Princeton before and after his stint in the Marines during World War II, and despite his Marine Corps training was disdainful of authority. He knew only one way to do things — his way.

And while neither Bradley nor van Breda Kolff could have anticipated the circumstances that would bring them together, once it happened, they found that they shared one very essential thing in common: how basketball should be played.

Bradley and van Breda Kolff “hit it off immediately,” Bradley told me in a recent interview. “We were absolutely in sync, and I learned a lot… He was an excellent coach, and his freelance offense was perfect for me.” For his part, van Breda Kolff quickly recognized Bradley’s all-around skills and made him the centerpiece of the team, despite being a sophomore.

Unlike many great basketball players, Bradley was not blessed with over-the-top athleticism. While he was a very good natural athlete, he wasn’t the fastest guy on the floor, or someone who could jump out of the gym. He was a great shooter, but he was also a team-first player, who was always looking to pass to an open teammate. Some of his greatest strengths were mental in nature: his preparation, execution, understanding of the game, and instinctive sense of where every player was on the court at all times. Van Breda Kolff had a very succinct view of what made Bradley different from other players: “Self-discipline.”

Van Breda Kolff's freelance offense had almost no set plays and required constant movement of both the ball and his players. He tried to instill in his players an ability to “read and react,” to be aware when a situation was opening up and to take advantage of it. This mindset was the precursor to what would become known as the Princeton Offense, with the backdoor play as its signature move.

The offense wasn’t specifically designed to get the ball to Bradley, but he was uniquely capable of exploiting the opportunities the offense created. He found shots by moving without the ball, understanding where to go on the court to get open for a high-percentage look.

Historically, Princeton had never done much recruiting, and it was said that Cappon had never set foot off campus to recruit a player. An alumnus might occasionally call the coach’s attention to an outstanding player who had the potential to meet Princeton’s academic requirements, and the player would be invited for a campus visit. But basically, Cappon had coached whoever showed up.

Van Breda Kolff, however, was an ambitious young coach on his way up. Whereas Cappon had been content to do well in the Ivy League and against regional rivals, van Breda Kolff had grander goals. He wanted to be able to compete against the best teams in the country, so he set out to recruit the type of players who could help him do it.

With his large personality and friendly style, van Breda Kolff was a natural recruiter. He was able to leverage the presence of Bradley and the team’s success during his first year to bring in what was undoubtedly the best group of freshmen basketball players ever assembled at Princeton.

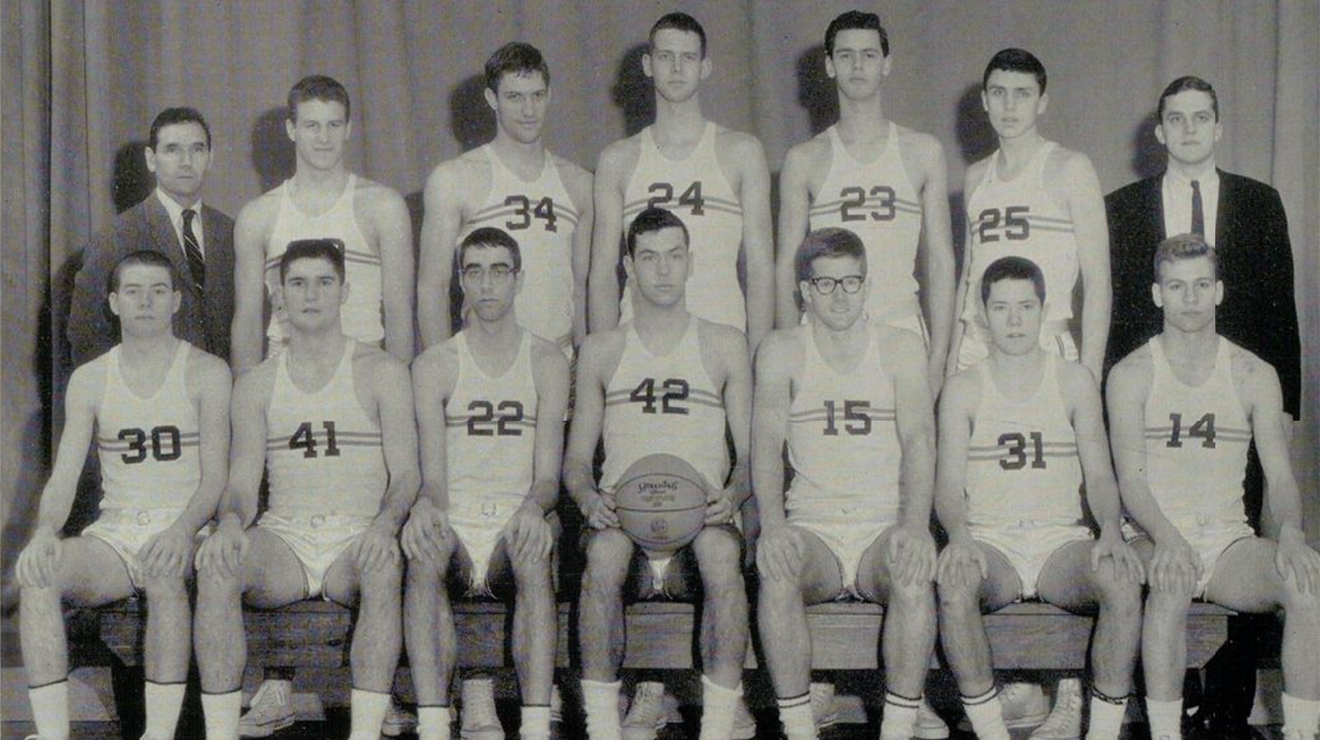

The key incoming players included Ed Hummer ’67, a 6-foot-7 high school All-American from the Washington, D.C. area; Gary Walters ’67, a 5-foot-10 point guard from Reading, Pennsylvania, whose high school coach, Pete Carril, had played for van Breda Kolff at Lafayette; and Robbie Brown ’67, who at 6-foot-10 was the tallest player to play for Princeton to that point.

Princeton enjoyed considerable success in Bradley and van Breda Kolff’s first two years together, winning Ivy championships and going to the NCAA Tournament both years. But it was in Bradley’s senior season, 1964-65, when van Breda Kolff’s prize recruits joined the varsity as sophomores, that the team fully burst on to the national scene.

College basketball games were rarely televised in those days, so few people had actually seen Bradley play. That changed when Princeton went up against No. 1 Michigan at the 1964 Holiday Festival in Madison Square Garden. In one of the most highly anticipated games of the season, featuring Bradley and Michigan star Cazzie Russell, Princeton led most of the way. Only after Bradley fouled out late in the game did the Wolverines rally to win on a jump shot by Russell with three seconds left.

Bradley had been magnificent, scoring 41 points, and despite the loss, his already sterling reputation as a player moved up a few notches.

Princeton proceeded to win its third straight Ivy championship and qualify for the NCAA Tournament again, an appearance that this time would be a momentous one.

Unlike today’s bloated March Madness, which includes 68 teams, the NCAA Tournament in 1965 had only 23. There were no easy matchups.

After squeaking by Penn State and beating North Carolina State convincingly, Princeton met fourth-ranked Providence in the finals of the NCAA Eastern Regional. The game wasn't close, as Princeton blew the Friars out of the water, 109-69. To this day, Bradley thinks of that game as “Coach van Breda Kolff basketball at its best.” He adds, “It was the best game a team I played on ever played, whether in high school, college, or the pros.”

The Tigers moved on to the Final Four in Portland, Oregon, where they met Michigan again in a national semifinal. The game was close until halftime, but Bradley again fouled out, and the Wolverines cruised to a 93-76 victory.

Bradley and the Tigers still had one last hurrah, in the consolation game against Wichita State. Princeton dominated from the start and held a comfortable 53-39 lead at halftime. Knowing this was Bradley’s last game, van Breda Kolff reputedly collared his star in the locker room, imploring him not to be so unselfish: “For crissake, Bill ... for once in your life, just shoot the goddamn ball!”

As the second half began, Bradley kept making almost every shot he took, and his teammates fed him the ball at each opportunity. He wound up with 58 points, making 22 of 29 shots from the field. It was not only Bradley’s personal high, but also an NCAA Tournament record for points in a game. Despite Gail Goodrich's outstanding performance leading UCLA to victory over Michigan in the NCAA championship game, Bradley was named Final Four MVP.

Bradley was a once-in-a-generation player: He still holds Ivy League records for points in a game (51), a season (464), and a career (1,253), even though during his time freshmen weren't allowed to play on the varsity, and the three-point shot lay nearly two decades in the future. He initially spurned the NBA and went to Oxford for two years as a Rhodes scholar. He then signed a record-breaking contract with the New York Knicks and helped lead them to two NBA championships during a 10-year pro career. He was well into his second career as a U.S. senator when he was voted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1983.

Van Breda Kolff remained at Princeton for two more seasons after Bradley left. His 1966-67 team finished 25-3 and ranked as high as No. 3 in the nation with a roster that many consider to be Princeton’s best of all time. Led by seniors Walters and Hummer, and underclassmen Chris Thomforde ’69, Joe Heiser ’68, and John Haarlow ’68, the Tigers played seamless team basketball, with all five starters averaging between nine and 15 points a game. Princeton reached the semifinals of the NCAA Eastern Regional, but, depleted by injuries to Haarlow and Walters, lost in overtime to a highly ranked North Carolina team that it had beaten by 10 points earlier in the season.

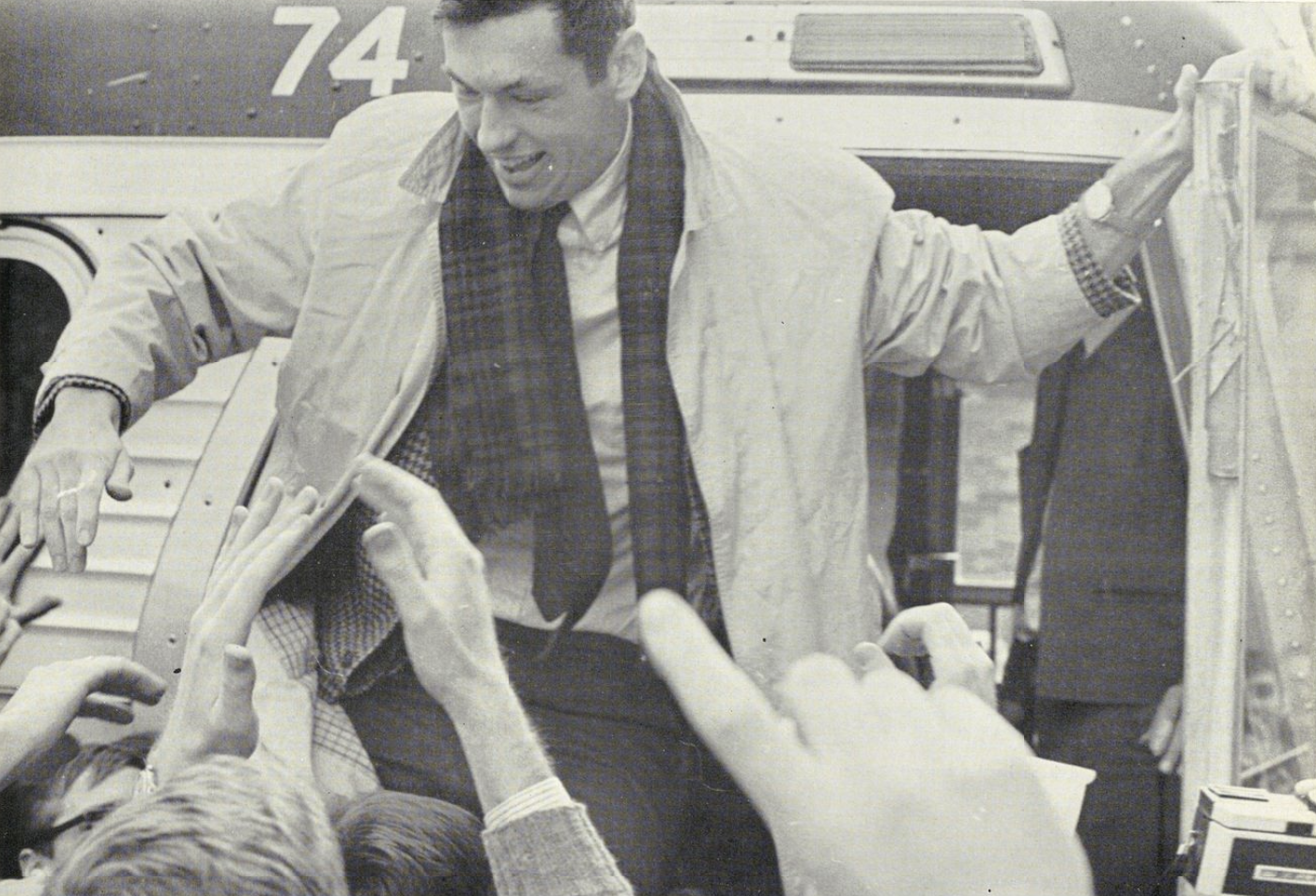

Shortly after that season ended, van Breda Kolff shocked the basketball world by leaving Princeton to become coach of the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers. He led the Lakers to two consecutive NBA finals but clashed with superstar Wilt Chamberlain and abruptly resigned. He resurfaced almost immediately as coach of the Detroit Pistons, beginning a coaching odyssey that ultimately included nine more stops, at every level of basketball.

Everywhere he went, the larger-than-life van Breda Kolff’s personality was on full display, developing over-achieving teams on his own terms, and relaxing afterwards with a few beers and a bar full of friends. He died on Aug. 22, 2007, at 84, after a long illness.

Though van Breda Kolff coached at Princeton for only five seasons, his influence has continued in an unbroken line to every Tiger coach since, directly or indirectly.

His hand-picked successor, Pete Carril, had played point guard on the first team van Breda Kolff coached. While Princeton’s athletic administrators were somewhat reluctant to hire a rumpled, 5-foot-6, cigar-smoking coach with only one year of college coaching experience, the added endorsements of Walters and Thomforde sealed the deal.

Van Breda Kolff and Carril had great respect for each other and similar basketball philosophies, but they came from very different backgrounds and went about coaching in starkly different ways. As one of the handful of players who was coached by both men, I can attest to that first-hand.

Van Breda Kolff was the son of a stockbroker and brought up in an upper-middle class household. As a good-looking, 6-foot-4 former NBA player with an infectious personality, his players both liked and respected him. He kept things loose at practices, which consisted mostly of scrimmages that simulated game situations.

Carril grew up in much less lofty circumstances. He was raised by a single father who had immigrated from Spain and worked as a steelworker in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. As a coach, at least early in his career, he was a perfectionist who was very demanding of his players. He planned out each practice in five-minute segments on a 3x5 card and created a tense atmosphere by relentlessly pointing out his players’ shortcomings.

When it came to expectations for their teams, van Breda Kolff was a realist and Carril a purist. “[Van Breda Kolff’s] goal was to take things as they are and build around them,” Carril once remarked. “I take things, and if they aren’t right for me, I try to change them.” Walters felt lucky to have been coached by both men, saying, “Carril gave me roots, and van Breda Kolff gave me wings.”

Carril coached Princeton for 29 years, winning 13 Ivy League titles. Among his many highlights was leading the 16th-seeded Tigers to a near upset of top-seeded Georgetown in the first round of the 1989 NCAA tournament. Sports Illustrated dubbed the game, which Princeton lost 50-49, as having “saved March Madness,” as it short-circuited the NCAA’s efforts to limit the tournament participation of schools from smaller conferences. Interest in the NCAA Tournament has since grown exponentially, with CBS and Turner Broadcasting now paying $1.1 billion per year for exclusive rights to carry the event through 2032.

In Carril’s last victory before retiring after the 1995-96 season, he led 13th-seeded Princeton to an upset of defending champion UCLA in the first round of the NCAA Tournament. Carril was voted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 1997.

Carril in turn was followed by a succession of head coaches who were mentored by him as either a player or an assistant coach: Bill Carmody, John Thompson III ’88, Joe Scott ’87, Sydney Johnson ’97, and current coach Mitch Henderson ’98, now in his 14th season, who took the 15th-seeded Tigers to the Sweet 16 in 2023.

Henderson, who played two years for Carril and later encouraged him to be a daily presence at practices during his first ten years as head coach, has steeped himself in the legacy of Princeton basketball. At its essence, he sees it as “four guys cutting off a skilled post player, making every possession count, and with a deep belief in making each other better on the court.”

While each coach has had his own personality, and many outstanding players have contributed their own unique skills, the style of play and success of Princeton’s teams has remained remarkably consistent ever since Bradley and van Breda Kolff joined forces in the fall of 1962.

Looking back from a distance of 60 years, Bradley feels his refusal to accept “that Princeton couldn’t play with the best teams in the country” may have been his most important contribution to the program. And the Tigers have been proving him right ever since.

Tom Chestnut ’70 played for both Butch van Breda Kolff and Pete Carril at Princeton. He later served as president of the NBA’s Cleveland Cavaliers.

9 Responses

Reed M. Benet ’84

1 Year AgoPerspective from a Fellow Marine

Going into the Marines after graduation seemed to make sense to me not only because roommate John Lowry III bullied me into dropping out of Army ROTC, but also because during my time at Princeton three of President Reagan’s cabinet members were Marines, and two were Princetonians (i.e. James Baker III ’52 and George Shultz ’42).

During a party as Tiger Inn social chair and as a politics major I certainly recognized then Secretary of State Shultz who showed up with two very large security guards.

I said, “Welcome, Mr. …?”

To which he responded, “Smith.”

I then said, “Welcome, Mr. Smith. By the way, how is that tiger tattoo on Mr. Smith’s ass?” He laughed.

So, always thinking Marine Corps, I saw PAW’s teaser for the Online Exclusive regarding Tom Chestnut ’70’s article on the 1962 pairing of subsequently Sen. Bill Bradley ’65 and basketball coach Butch van Breda Kolff ’45.

Your teaser said that van Breda Kolff was disdainful of authority despite his Marine training, and this got me thinking of a constant interaction I have with my wife Jacqueline, aka “the Marine Corps Colonel’s daughter.”

When we make the bed together, she says, “I thought you were in the Marine Corps — where are those hospital corners?”

To which I, disdainful to authority respond, “Honey, I don’t do hospital corners and will never again because I was in the Marine Corps!”

By the way, when people ask how long I served in the Marine Corps, I say, “Four years active duty plus 35 years and counting of marriage.”

Semper Fidelis!

Andy Steele ’69

1 Year AgoThanks for the Memories

Great article, Tom. Thanks for the memories. You are still a ’69er in our hearts! Hope you will join us at ’69 reunions!

Jerome P. Coleman ’70

1 Year AgoButch as a Coach (and as a Knick)

Kudos to Tom Chestnut for an insightful, heartfelt and well-written piece.

Butch was a players’ coach who magnified our love of the game. Two-hour uptempo practices, intense scrimmaging, and pauses to both instruct and criticize. Lots of tears when he left.

Butch encouraged physical play, hustling, rebounding, diving for loose balls. Bud Palmer, his teammate at Princeton and the Knicks who later became a smooth sports commentator, when asked what kind of player Butch was with the Knicks replied he would dive six rows into the seats to try to retrieve a ball going out.

Notice how thin the players were at the time. We had no strength coaches but I thought it would be wise to add some muscle and eventually found my way to the weight room tucked away in a remote corner of Dillon. It was packed with grunting and unfriendly footballers who looked at me in disdain; my last trip to the venue.

Again, thanks ’Nut; fond memories. Well done.

Michael Witte ’66

1 Year AgoFrom Crystal City to Old Nassau

Hey Tom,

Excellent piece.

I have one of the earlier connections to the Bradley story; I grew up in St. Louis and was reading of the exploits of someone named Bradley in both the St. Louis Post Dispatch and Globe Democrat. A basketball player myself, I was curious about a possible competitor (Ha!) and, turning 16, drove to a local tournament in which Crystal City was playing. I watched Bradley. “Not bad,” I thought. “Sixteen, maybe 17 points.” Next morning, the local sports pages bannered: “Bradley Scores 36 in Crystal City Win.”

From that point, I was hooked and followed Bradley in his Missouri career (including a triple-overtime state tournament game against Mercy in which Bradley casually dished the winning basket surrounded by all five opposing players). Then on to Princeton where I failed to make the freshman team (Ha!). I have been following this amazing man ever since — a near life-long privilege.

Jeff Chokel ’68

1 Year AgoBill Bradley Stories

I remember two encounters with Bill Bradley:

As a freshman I was in the locker room at about 6 p.m. after squash practice talking with the coach, Bill Summers. In walked a student who checked out a basketball and looked around for someone to play with. He asked me to join him, and Coach Summers said, “Go ahead, Jeff.” I had no idea who he was but for five minutes took bounce passes and jump “shots.” He then returned the ball and gave me a funny look as he walked away. The coach said, “Good luck tonight, Bill.”

I had to ask who this student was. That night I watched him play and realized I could always say I played basketball with Bill Bradley in 1964.

Three years later I was writing with the University Press Club assigned to cover Princeton for The New York Times. At 11 p.m. I received a call from the sports editor asking if Bill Bradley had returned to Princeton immediately after his first appearance playing with the New York Knicks. I checked with sources and called the number for John McPhee’s home. John called Bill to the phone to talk with me. I said The New York Times wanted to talk with him. Bill said he didn’t mind talking to me, but didn’t want to talk to them. I quickly got some quotes and at midnight called them in for the next day’s paper. That month I received a nice bonus in my monthly check for helping out the Times.

Bruce Hultgren ’68

1 Year AgoAppreciation from a Longtime Basketball Fan

An excellent synopsis of a great story. It certainly brought back memories for me. I have remained a Princeton basketball fan for all these years, and enjoy the team basketball the Tigers play to this day.

Thank you for the insights into VBK and Pete’s backgrounds. I knew part of the story but this clarified some details.

I agree with Greg Purcell’s comment — always fun to have Tom around, especially around that card table.

Marc Lackritz ’68

1 Year AgoEvocative Story of Basketball History

Great story, ‘Nuts, and many thanks — for evoking great memories of “a time long ago in a galaxy far, far away!”

Shiv Mohan Dutt ’11

1 Year AgoEssay Kudos

Beautifully written, thank you for sharing this wonderful story.

Greg Purcell ’69

1 Year AgoBasketball’s Golden Era

Tom, this was a great article. That was the golden era of Princeton (and Ivy League) basketball. What I remember about you at Tower Club is that you were much closer to being a van Breda Kolff than a Bradley. When Tom was around the fun was sure to follow!