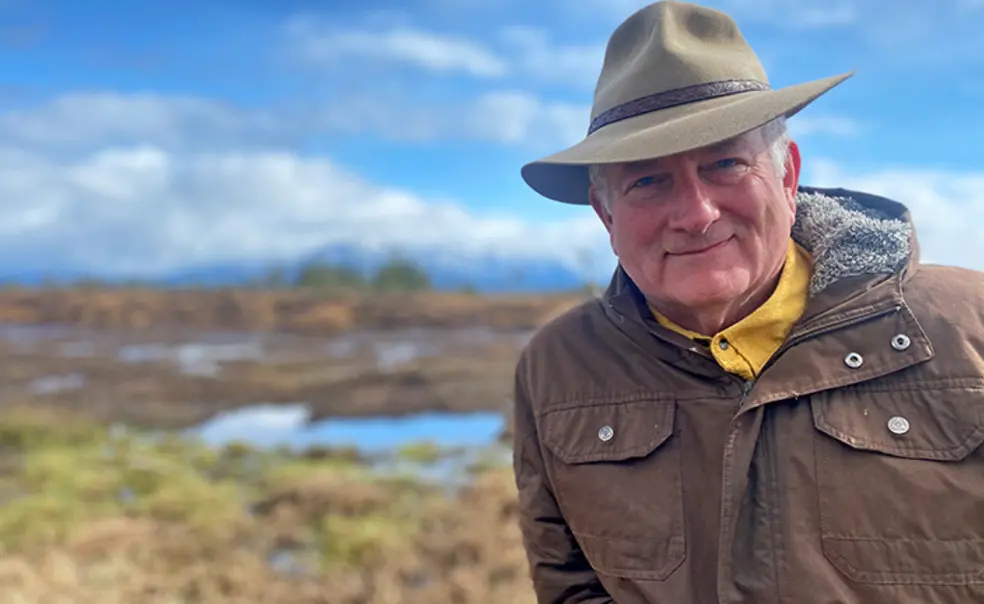

Bill Urschel ’78 Is Documenting Climate Change in Alaska

‘If we can share some of the wonders of Alaska with others, we believe that people will care more about the natural world’

A few months after COVID-19 reached America’s shores, Bill Urschel ’78 weighed anchor. He and his wife, Patsy Clark Urschel — both of whom had by then moved aboard a 72-foot steel-hulled research vessel called the Endeavour —motored from Seattle up to the Gulf of Alaska, where they began hosting scientific expeditions in some of the fastest-warming waters on the planet. Their goal: to shed light on Alaska’s rapidly changing environment.

“We gave up the house and the cars and most of the things we didn’t need,” wrote Urschel on his online Logbook, to which he posts lyrical dispatches from the Endeavour’s odyssey. “This isn’t a simple life … But we wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. Every day, in every season, we’re marinated in the awesome and delicate beauty of one of the wildest places left on Earth. We feel alive.”

For most of his career, Urschel was a West Coast tech entrepreneur, starting a number of software companies that drew him away from his true passions — history, conservation, and writing. He bought the Endeavour in 2007, having just sold a company to Microsoft, and in the spring of 2020, with children “grown and launched” and a pandemic sweeping America, he and Patsy realized that it was time to leave the harbor.

“We just decided that life was getting too short,” said Urschel. “This is a wonderful way to live. We call it, ‘living pelagic.’”

Shortly after reaching the Gulf of Alaska, the Urschels founded Alaska Endeavour, a nonprofit that aims to advance scientific understanding of Alaska’s natural environment and to educate the public about its findings. Already, the Endeavour — which is “cheap to run and tough as an axe” — has taken glaciologists to conduct research in the Kenai Fjords, geologists and paleontologists to study Alaska’s Lost Coast, and a group of biologists to study humpback whale populations in Sitka Sound. This research has pointed to troubling trends in Alaska’s natural environment.

“Much of the science comes back to climate change,” said Urschel, who noted that the region’s glaciers are retreating at an accelerating rate, and that its humpback whale population is showing clear signs of stress. Alaska is warming roughly twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and its marine and coastal ecosystems are facing extreme destabilizing pressures.

Urschel has largely self-funded the expeditions so far, but he has begun to receive sponsorships and donations from outside sources. In addition to publishing written accounts on Alaska Endeavour’s Logbook, he is now producing a television show, which he hopes will air on a major network.

“If we can share some of the wonders of Alaska with others, we believe that people will care more about the natural world,” he explained. “Through understanding comes appreciation, and through appreciation comes conservation.”

Urschel’s career in storytelling began at Princeton, where he took Professor John McPhee ’53’s legendary journalism course, “Creative Nonfiction.” McPhee’s Coming into the Country (1976) — a book that paints a rich portrait of Alaska in the years following its 1958 statehood — deeply influenced Urschel.

“I think of John McPhee every single day I sit down to write,” he said. “I give Draft No. 4” —another of McPhee’s books — “as a present to all of my writer friends. That is, to those who don’t already have it.”

As fieldwork for his senior history thesis, Urschel rode a horse 1,200 miles across the American southwest, following the route of Stephen Watts Kearney’s 1846 expedition to the Pacific Ocean. After graduating from Princeton, he spent a decade traveling and working as a freelance writer. He was in Nicaragua when it fell to the Sandinistas and in El Salvador when the Salvadoran Civil War began. He paddled a dugout canoe down Peru’s Ucayali River and was captured by an indigenous tribe. But while he managed to make a living as a travel writer, he found he could make more money writing about computers, and soon he launched his first software company.

“I got seduced away from writing by the money,” he recalled.

More than three decades later, he has returned to the pursuits and ideals of his youth.

“I have pretty much gone back to my Princeton self,” he said.

No responses yet