Biologist Wenfei Tong ’05: The Birds and Bees of Birds

“I thought, ‘Wow! Living outdoors and watching wild animals and studying them?’ I didn’t know you could do all those things,” said Tong, who is a Harvard research associate.

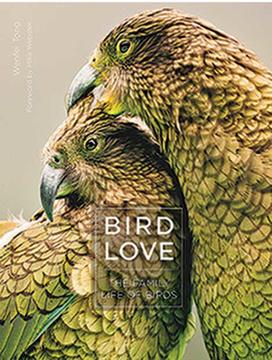

The revelation propelled her to Princeton — where she studied with the Grants and other mentors as an ecology and evolutionary biology major — and to fieldwork, just as she had hoped. Now, her passion has resulted in a new book called Bird Love: The Family Life of Birds (Princeton University Press), an overview of the extraordinarily diverse ways birds mate and raise chicks.

There are many remarkably familiar characteristics of avian “dating” and family life. Male birds dance, pose, or parade to attract females. Female flamingos secrete reddish oil that they use like makeup, brushing it onto their necks and body feathers to look more attractive. Some birds mate with as many partners as possible, while others are monogamous — but still “cheat” on their partners (something we know from DNA paternity tests). And female bowerbirds value brains over beauty, so the males demonstrate their creativity by constructing elaborate structures of grass, twigs, pebbles, and other found objects, complete with soaring entryways, long avenues, and decorated courtyards.

The bird world can seem downright sexist. The female is often the one left to care for offspring, “though birds are better than a lot of mammals because there are usually two parents sharing childcare duties,” Tong said. For that reason, Tong — a feminist — also included a chapter on sex-role reversals. While most male animals have evolved to be the ornamented and aggressive parent that leaves the female with the baby, some bird species have evolved to be the opposite.

Beyond her academic work, Tong moonlights as a birding and nature tour guide. “It’s just so rewarding to get other people excited about something I love,” she says. As with her tours, she hopes people come away from her book feeling a sense of kinship with birds.

“Like everyone, I’m disturbed by the whole environmental situation, so anything that gets everyone to like the natural world is really important,” she says. “My motive is to make people [understand] we’re not separate from the natural world. So you could say my aim is conservation.”

No responses yet