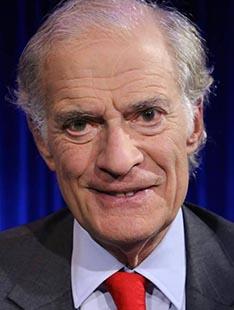

Attorney James D. Zirin ’61 had already completed a draft of Supremely Partisan: How Raw Politics Tips the Scales in the United States Supreme Court (Rowman & Littlefield) when Justice Antonin Scalia died in early 2016. Zirin says what followed — Congress blocking a vote on Obama nominee Merrick Garland and presidential candidate Donald Trump’s promise to appoint a pro-life justice — laid bare an “irrefutable fact”: the Supreme Court has become fiercely partisan in how justices are appointed and cases are decided. Zirin spoke to PAW about the new nominee Neil Gorsuch and how the federal government’s umpire has turned into one of its most active players.

What should be the role of a Supreme Court justice?

No judge should “legislate from the bench,” or act as a moral philosopher or an ethicist deciding what in his or her view achieves some desired social end or policy. In Justice John Marshall’s words, the judge’s role in the constitutional system is “expounding,” not redrafting, the Constitution.

You say the Supreme Court is more politically polarized than ever. How did you determine that?

The court has often appeared to be politically influenced. But since the appointment of Justice Scalia in 1986, it has never been so polarized, with 5-4 and 6-3 decisions decided along partisan lines.

Both presidential candidates expressed a definite view as to the necessary ideology of Supreme Court justices. Hillary Clinton, for example, said that she wanted justices who would defend women’s [and] LGBT rights, support Roe v. Wade, and reverse the Citizens United decision and its ability to funnel dark money into elections.

How does the process that led to Trump’s nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch support your thesis that the court has become supremely partisan?

Trump in the campaign said he would appoint a justice who would “automatically” overrule Roe v. Wade, of “similar views and principles” to Justice Scalia. Gorsuch, a Scalia admirer, with strong conservative Republican bloodlines, fits the bill quite nicely. He referred admiringly to Scalia in his speech at the White House.

In the history of the Supreme Court, are there any analogs to the way the Republicans politicized this nomination process, which The New York Times Editorial Board called a “stolen seat.”

The closest analogy is the [Robert] Bork nomination when Democrats started the fight by rejecting a highly qualified candidate for his ideology. In the last half century, the Senate has formally or informally rejected eight nominees. [Abe] Fortas and [Homer] Thornberry were rejected because they were cronies of Lyndon Johnson; [Clement] Haynsworth and [G. Harrold] Carswell were rejected because of allegedly racist views; [Douglas H.] Ginsberg was rejected because, as a professor, he had smoked marijuana with his students; George W. Bush withdrew Harriet Miers’ name because of bipartisan opposition. Only Bork and Garland have been rejected on ideological grounds.

What if anything can be done now by Congress to depoliticize the process? Is there any way to walk this back from the precipice?

The framers of the Constitution intended a political process. We have now a deeply polarized nation. Our think tanks are polarized, our universities, media, Congress, and indeed the Supreme Court. Unless the nation comes together, we are unlikely to see a change for some time to come.

According to an academic study of past decisions, Judge Gorsuch closely shares the conservative legal philosophy of Justice Antonin Scalia. In your book, you specifically point to the Hobby Lobby religious freedom case — and Gorsuch was part of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruling on that matter, which was upheld by the Supreme Court — as an example of a controversial partisan decision. What does his nomination say about the politicization of the court?

The politicization will continue with regard to the hot button issues: guns, gays, God, and abortion. Gorsuch, if anything, is to the right of all the other conservative justices, except perhaps Clarence Thomas — whose views of natural law he likely shares. If confirmed, the 5-4 conservative balance will likely continue. Gorsuch may lack Scalia’s intellectual heft, but he is nonetheless very able. And at age 49, he could serve another 40 years or more.

Record numbers of rural whites voted in the recent election. Should that group be better represented on the court (as it was in the past)?

There is no requirement that the justices represent all voting blocs. That said, all of the present justices come from the East or West Coast; all attended either Harvard or Yale Law Schools; all but one was promoted from the lower federal appeals courts; and all but one spent a good deal of their careers in Washington.

Other than being from Denver, Judge Gorsuch fits that mold. What are the consequences of that?

When Scalia was around, there were six Catholics and three Jews on the Court — no white Anglo Saxon Protestants. There have been 112 justices (Gorsuch would be 113). Eighty-nine of these have been White Anglo Saxon Protestant males. Gorsuch adds a measure of diversity as he is an Episcopalian, although in my view, a likely vote to overrule Roe v. Wade.

Other than that, Gorsuch fits the mold neatly. Although he lives in Colorado, he grew up in D.C. His education is Ivy League, and he has served as a federal appellate judge like seven of his possible colleagues (Elena Kagan is the exception). He adds little in the way of diversity.

If the most conservative wing of the court had its way, what laws could be overturned?

The most conservative of the justices, Clarence Thomas, has said he wants to overrule all decisions he deems contrary to the Constitution. These might include not only Roe v. Wade (which has been reaffirmed at least twice), but also the 14th Amendment, whose due process clause makes the Bill of Rights applicable to the states; decisions questioning capital punishment and how it is administered; well-settled decisions making children of alien parents citizens of the United States; decisions forbidding the prosecution [and denaturalization] of flag burners; decisions upholding press freedoms; and decisions an unassailable divide between church and state. No other justice, including Scalia, has gone this far. Scalia said in this regard: “I may be an originalist, but I am not a nut.”

What did you think of President Trump’s nomination process?

The appointment process had every element of a reality TV show or perhaps the crowning of Miss Universe. The runner-up, Thomas Hardiman of Pittsburgh, drove to Washington where he waited in the wings for the decision. The announcement, moved up two days to divert media attention from the travel ban, was televised in prime time with Mrs. Scalia in attendance. All great political theater.

Will the court get more partisan in the years to come?

With President Trump vowing to appoint justices who will “automatically” overrule Roe v. Wade and uphold gun rights, and with the specter of at least three vacancies in the next four years [Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Anthony Kennedy, and Stephen Breyer are over the average retirement age for justices], the court will become increasingly partisan in how justices are selected and cases are decided. Given the current composition of the Senate, a Trump nominee needs to muster 60 votes for confirmation. These would have to include the votes of Democratic senators, who now must be the guardians of our well-settled constitutional liberties. The confidence in the Supreme Court of a politically divided nation hangs very much in the balance.

Interview conducted and condensed by Dan Grech ’99

1 Response

Randal Marlin ’59

9 Years Ago“No judge should...

“No judge should ‘legislate from the bench,’ or act as a moral philosopher or an ethicist deciding what in his or her view achieves some desired social end or policy.”

Against that I would recall (and I am relying entirely on memory) Justice James Fitzjames Stephen’s view in R. v. Tolson where he cites the centuries old case of Fowler v. Padgett, where a judge says, and I am paraphrasing, that he would stretch the meaning of words any distance to avoid a manifest injustice.