A British obsession

Anthony Brandt ’58 recounts a country’s search for the Northwest Passage

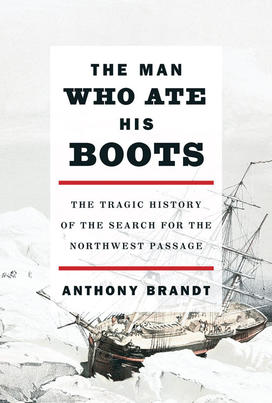

In the summer of 2007, the fabled Northwest Passage — a maritime shortcut from Europe to Asia through northern Canada — was free of ice and allowed smooth sailing for the first time, thanks to global warming. This provided an unexpected coda to the elusive, centuries-long quest to find a route through the frigid Arctic waters, a search recounted in painstaking detail by Anthony Brandt ’58 in The Man Who Ate His Boots: The Tragic History of the Search for the Northwest Passage.

Brandt explores how the search became an obsession for 19th-century Britain, which sent out expedition after expedition in vain — bookended by two attempts by explorer John Franklin. On the first, between 1819 and 1822, Franklin led 20 men overland starting in Canada at the mouth of the Hayes River in search of the northern coast of Canada; after misjudging the timing of their return, only nine survived weather conditions and deprivations so severe that they were driven on several occasions to eat their own leather footwear.

More than two decades later, in 1845, Franklin led another expedition with 129 men and two well-stocked ships that was intended to find the passage through northern Canada once and for all. After some initial progress, the ships got stuck in the ice beginning in September 1846. Running out of supplies and without ready access to food, the men abandoned ship in April 1848. But they were 1,000 miles from the nearest fort, and over the next six months, they all died, one by one, from starvation and exposure. Rescue efforts continued for a decade, failing to find survivors but providing scattered evidence of what had happened, including archaeological proof that some took to cannibalism before the bitter end.

For Brandt, whose book was published by Knopf in March, the Arctic explorations offer a bracing mix of heroism by the explorers and folly by the admirals back in London. “Most of us try something once, maybe a second time, but by the third time we’ll say it’s not working,” Brandt says. “But the British always came up with a reason why something didn’t work, and why the next time it would.”

Brandt, who edited the now-discontinued Adventure Classics book series published by National Geographic Society Press, also served as books editor of National Geographic Adventure magazine, and earlier in his career spent seven years as the personal historian for Sherman Fairchild, a pioneer in aviation and aerial photography.

Brandt sees the attraction of the adrenaline rush from exploration, but for his historical study of the Northwest Passage, he didn’t feel it was necessary to visit Canada’s frozen north firsthand.

Today, the land Brandt writes about remains barely populated, though it’s now possible to take a luxury cruise through the passage on a Russian icebreaker or stay at a hotel where you can board snowmobiles to tour the “Franklin trail” where his men perished.

Louis Jacobson ’92 is a staff writer with PolitiFact.com.

No responses yet