Chip Kaufman ’71 Brought New Urbanist Ethos to Australia

Kaufman and his wife Wendy Morris inspired Australians to take up the cause of ‘walkable neighborhoods’

The sequel to this story is how one of Princeton’s New Urbanists, Chip Kaufman ’71, with his wife, Wendy Morris, exported this ethos beyond America, to the sunbaked shores of Australia.

Most important, Kaufman and Morris inspired a generation of Australian citizens, planners, and politicians to take up the cause of “walkable neighborhoods,” using the design workshops that are a hallmark of the New Urbanist design process.

At Princeton, Kaufman majored in architecture alongside fellow New Urbanists Andres Duany ’71, Stefanos Polyzoides ’69, and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk ’72. But his passion lay in drawing and painting. “Architecture was the closest creative major I could think of. I didn’t lift a hammer or really understand architecture until well after school.”

By 1974, Kaufman had given up architecture to pursue fine art, until a “serendipity” brought him back to the field. “I was shooting old buildings for the Texas Historical Commission when I discovered a historically intact town on the Guadalupe River while kayaking.” Struck by its beauty, Kaufman ended up directing the adaptive reuse of the abandoned 30-building town, called Gruene — which had been slated for demolition before Kaufman successfully argued for its revitalization.

Gruene taught Kaufman the lessons of town construction from the floorboards up. “It was there that I began to actually understand about building — how far 20 feet is, what an empty space feels like.” Inspired, Kaufman moved to Sacramento, California, and started his own architecture firm.

In 1989, Duany, Kaufman’s classmate, visited nearby Berkeley to lecture on the architectural theories he was developing with his wife, Plater-Zyberk — ideas that would soon be known as New Urbanism.

“Afterward I went straight to Andres, grabbed him by the neck and said, ‘Please, Andres, I want to volunteer. Let me learn as much as possible with you.’” Kaufman spent the following years learning the ropes of New Urbanist design.

In 1991, Wendy Morris, a leading Australian urban designer, wrote to Duany and Plater-Zyberk requesting that an expert come Down Under to lead design workshops. Kaufman volunteered — and three years later, he moved to Australia to live and work with Morris.

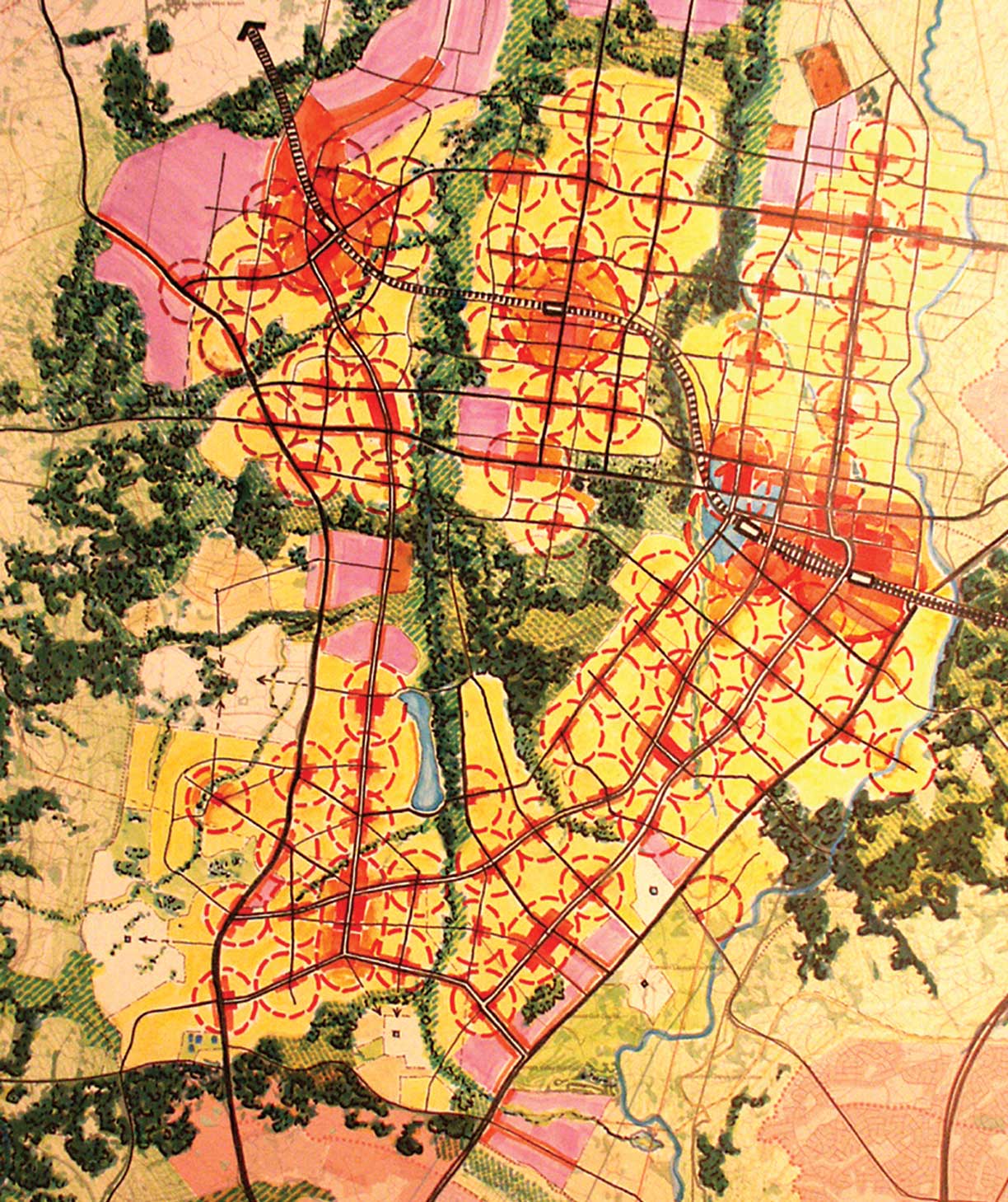

One of the couple’s big projects in the late 1990s involved helping to draft the “growth code” for the state of Western Australia, which was “on the verge of perpetuating textbook sprawl,” says Kaufman. He and Morris led a five-day design workshop for Western Australia, and by the end, the planning office head was convinced.

In recent years, Kaufman has stepped away from architecture to return to his first loves: painting and whitewater kayaking.

“Their work is still being built to this day, because in Australia things take so long to be implemented,” said Brian O’Looney, a New Urbanist architect and scholar who has collaborated with Morris and Kaufman on several projects. In the meantime, O’Looney said, Morris and Kaufman’s designs for Australian cities easily hold up to any of their stateside New Urbanist counterparts.

No responses yet