Choosing between two great works

Andrew Robison ’62 *74 explains which of these drawings he would choose to save if disaster struck

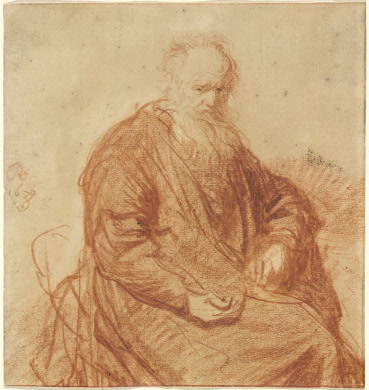

“I simplify the comparison by choosing two drawings by the same unquestionably great artist, both in the same general period of his work, in the same technique, and about the same size. The first is a fine example of Rembrandt’s distinctive interest in aged figures, and his extraordinary sensitivity in portraying their nobility; and it has great historical importance as Rembrandt’s earliest signed and dated drawing. However, if I had to choose, I would choose the second: it is Rembrandt’s finest early self-portrait drawing, wonderfully conveys his bold confidence and elegant attire of success at this period, and is astonishing in how he can use such a widely scattered variety of apparently casual short strokes, curves, and zig-zags to coalesce into a brilliantly lit image of his riveting gaze, fleshy face, wild hair and soft, textured beret.”

– Andrew Robison ’62 *74, Andrew W. Mellon senior curator of prints and drawings at the National Gallery of Art

No responses yet