Chronicling Football’s First Games

Parke H. Davis, Class of 1893, was a football aficionado whose undergraduate days overlapped with those of Princeton gridiron legends like Knowlton “Snake” Ames 1890, Phil King 1893, and Johnny Poe 1895. He played on the line for the Tigers and later coached the sport at Wisconsin, Amherst, and Lafayette, leading the Leopards to a 11-0-1 record in 1896, including a scoreless tie against Princeton. But Davis’ lasting influence came on the printed page, where he chronicled the early days of college football and mined the archives to crown past national champions. The following story about the first intercollegiate game (with a brief mention of the Princeton-Rutgers rematch a week later) ran in PAW in 1909. This week, the college football world will celebrate the 150th anniversary of that kickoff in New Brunswick.

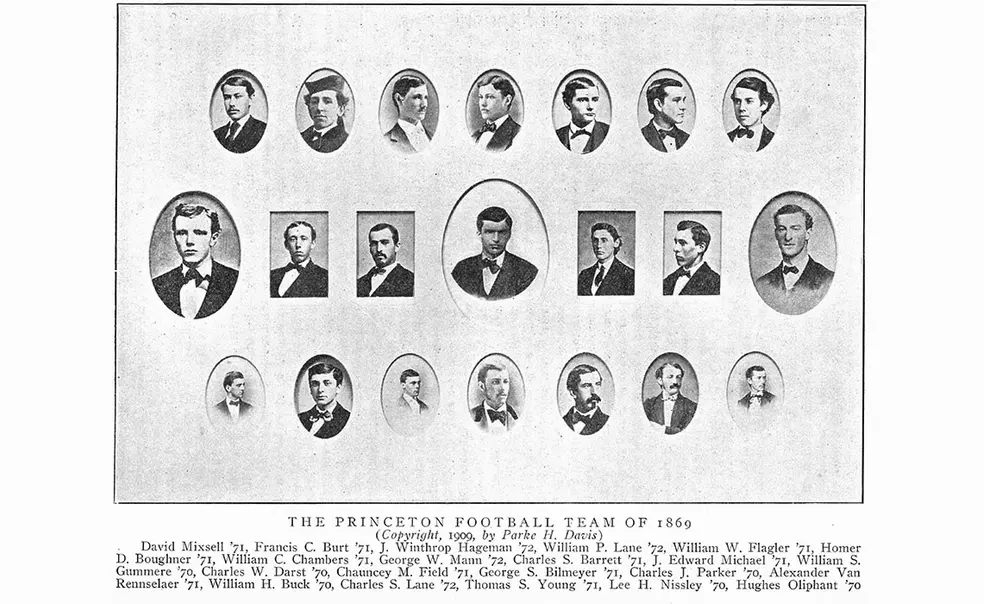

Davis could only identify 21 of Princeton’s 25 players in the first game (pictured above) when he wrote this story. Amateur historian David Nathan ’90 has since added three more to that list, but his search for the 25th man continues. Read more in Nathan’s column for PAW’s Oct. 22, 2014, issue.

Also, as Davis notes, kicking played a significant role in the early game, much more than it does in modern football. Read about American football’s rugby and soccer roots in PAW’s Oct. 23, 2019, issue.

The First Intercollegiate Football Game

By Parke H. Davis, Class of 1893

(From the Dec. 15, 1909, issue of PAW)

Saturday, November 6, 1909, marked the 40th anniversary of the first game of intercollegiate football played in America. The contest was between Princeton and Rutgers at New Brunswick, November 6, 1869.

In these days of prodigious publicity for the great battles of the gridiron it is startling to realize that up to the present time no account, either by contemporary or historian, has ever been published of this initial struggle, which by its very priority is entitled to historical precedence over all other celebrated football games. The heroes of the lime-line field of 1909 may read of their exploits and see their faces in the public prints within one hour after their achievement. The football heroes of 1869 have grown gray with the lapse of 40 years before their deeds and faces have obtained a place in the public chronicles of the game.

Football history, like all other history, must suffer from the uncertainty which invariably cloaks an original occurrence. Thus of this first game it is impossible today to compose a complete list of the players participating or to present all of the interesting incidents which were features of this quaint contest. Much, however, has escaped oblivion in the lack of records and the lapse of memory that is worthy of preservation as a most important part in the history of America’s major intercollegiate sport.

Those who are familiar with the history of college baseball will be surprised not at the earliness of the date of this game, but at its lateness, for the diamond preceded the gridiron by a full decade, the first intercollegiate baseball game being the contest between Amherst and Williams, July 1, 1859. Baseball, however, had in its infancy the stimulus of the sound and uniform set rules adopted at Cooper Institute, in New York, March 9, 1859, in the convention at which came into existence the National Association of Baseball Players.

The marvelous outburst of baseball at the close of the Civil War greatly stimulated the evolution of football — for with baseball first appeared the intra-college contest between class and class and organized club and club. The scores of this period disclose the fact that the college nines were superior to the professional teams and that the game was so popular that the colleges not only had a season in the fall as well as in the spring, but that their teams would not disband for summer vacation, preferring to tour the country, playing the Eckfords, the Tri-Mountains, the Resolutes, Atlantics and other famous nines of the day. With the arrival of the frosty, stinging days of late October not even a Spartan can withstand catching a baseball, so the organized teams naturally transisted to football. With the extensive intercollegiate relationships of this period in baseball it would seem that intercollegiate football should have arrived with a rush, but it was years before such a challenge even was discussed, due to the absence of common rules of play at the various colleges.

Princeton and Rutgers are near neighbors. Naturally the evolution of this sport was along similar lines, and the styles of game played almost identical.

On May 5, 1866, Princeton had heavily defeated Rutgers by 40 runs to 2 in their first baseball game. In the early fall of 1869 the student sentiment at New Brunswick therefore was rife for a further tilt with Princeton, and the agitation centered upon football as the medium of conclusions.

The leading campus players organized and elected William J. Leggett ’72, as their captain. A challenge then was framed in the punctilious form of that period and forwarded to Princeton. This defiant but courteous document invited the men of Nassau Hall, for the name Princeton as a university title had made its first appearance only the preceding spring on the shirts of the baseball nine in the game against the Athletics, April 21, 1869, to play a series of three games, the first at New Brunswick, the second at Princeton and the third also at New Brunswick. It is impressive to think in passing how the popularizing of the name of Princeton by the athletic teams eventually supplanted the official title of the college.

The receipt of this challenge aroused great enthusiasm at Princeton. William S. Gummere ’70, one of the leading campus players and a famous fielder on the college nine, was chosen as captain. Fortunately for the history of football Gummere also possessed another qualification which in life’s career has carried him to the position of Chief Justice of the State of New Jersey — a legal mind. Foreseeing that the first requisite for a game of intercollegiate football was a sound code of rules, he immediately commenced the settlement of these preliminaries in conjunction with Captain Leggett. The only difficulty arose in the disposition of a free kick. At Princeton a player catching the ball on the fly or first bound was entitled to have a space of ten feet cleared before him and without hindrance to have therefrom a free kick at the goal. At Rutgers no such play was known. This point was adjusted by providing for no free kicks in the game at New Brunswick, but allowing the play in the game at Princeton.

The rules for this contest are interesting, and being the first set of football rules formulated in this country, of course are of great historical importance in the game. They were as follows:

- Grounds must be 360 feet long and 225 feet wide.

- Goals must be 8 paces.

- Each side shall number 25 players.

- No throwing or running with the ball; if either it is a foul and the ball then must be thrown perpendicularly in the air by the side causing the foul.

- No holding the ball or free kicks allowed.

- A ball passing beyond the boundary by the side of the goal shall be kicked on from the boundary by the side who has that goal.

- A ball passing beyond the limit on the side of the field shall be kicked on horizontally to the boundary by the side which kicked it out.

- No tripping or holding of players.

- The winner of the first toss has the choice of position; the winner of the second toss has the first kick-off.

- There shall be four judges and two referees.

The date of the first game, Saturday, November 6, 1869, arrived. Despite the primitiveness of the occasion the jerky little train that steamed out of Princeton at 9 o’clock on that memorable morning was crowded to aisles and platforms with a freight of eager students. In 1869 and for many years later an unaffected, old-fashioned hospitality was observed among the colleges toward one another to a degree that is almost unbelievable in the rude lack of proprieties that characterizes the present period. A baseball game was far from the formal fixture it is today. It was a social event without superior in the life of a college. Rutgers accordingly in a mass met their visitors at the station and devoted the day exclusively to their hearty entertainment.

The game was called in the afternoon at 3 o’clock. The field selected was part of a vacant lot directly across the street from the present athletic field at Rutgers. The events immediately preceding the game were as primitive as the game itself. The spectators who had arrived early appropriated seats upon the top board of a fence which partly surrounded the field, while the others found places upon the ground. There was no admission fee, no waving of flags. The famous orange and black was antedated by seven years. But there were college songs, and, strange to say, a college cheer, Princeton’s booming rocket call, hissing and bursting, just as it does today. The players arrived a few minutes before 3 and, simply laying aside their hats, coats and vests, stood accoutred for the game, the only touch of costume being red turbans which were worn by the Rutgers men, a fashion long copied thereafter by other college teams. The Princeton 25 appeared to be much larger and heavier than their opponents. While the spectators were giving the players some preliminary advice the officials and captains were adjusting an objection to the very small size of the ball provided. With these preliminaries out of the way, time was called.

Of the players who lined up only the following can now be recalled:

PRINCETON

W. S. Gummere ’70

W. H. Buck ’70

L. H. Nissley ’70

H. Oliphant ’70

C. J. Parker ’70

H. D. Boughner ’71

G. S. Bilmeyer ’71

C. W. Darst ’71

W. C. Chambers ’71

W. W. Flagler ’71

C. M. Field ’71

C. S. Barrett ’71

F. C. Burt ’71

J. E. Michael ’71

A. Van Rensselaer ’71

T. S. Young ’71

David Mixsell ’71

G. W. Mann ’72

C. S. Lane ’72

W. P. Lane ’72

J. W. Hageman ’72

RUTGERS

E. D. De Lamater ’71

S. G. Gano ’71

W. J. Hill ’71

W. S. Lasher ’71

G. E. Pace ’71

C. L. Pruyn ’71

J. H. Wyckoff ’71

T. W. Clements ’72

E. D. Gilmore ’72

J. W. Herbert ’72

G. H. Large ’72

G. H. Stevens ’72

C. H. Steele ’72

J. A. Van Neste ’72

F. E. Allen ’73

M. M. Ball ’73

G. R. Dixon ’73

D. T. Hawxhurst ’73

P. V. Huysoon ’73

A. I. Martine ’73

C. Rockefeller ’73

J. O. Van Fleet ’73

G. S. Willits ’73

C. S. Wright ’73

The tactical organization of this large number of players was the same on both sides. Two men were selected by each team to play immediately in front of the opponents’ goal and were known as “captains of the enemy’s goal.” These positions for Princeton were filled by H. D. Boughner and G. S. Bilmeyer and for Rutgers by G. R. Dixon and S. G. Gano. The remainder of each team was divided into two sections. The players of one section were assigned to certain tracts of the field, which they were to cover and not to leave. These players were known as “fielders.” The other section was detailed to follow the ball up and down the field. These latter players were called “bull-dozers.” They are easily recognizable in the evolution of the game as the forerunners of the modern rush line.

The toss of the coins for advantage gave Princeton the ball and Rutgers the wind. Amid a hush of expectancy among the spectators Princeton “bucked” or kicked the ball, precisely as it is done today from a tee of earth, but the kick was bad and the ball glanced to one side. The light, agile Rutgers men pounced upon it like hounds, and by driving it by short kicks, or “dribbles,” the other players surrounding the ball and not permitting a Princeton man to get near it, quickly and craftily forced it down to Old Nassau’s goal, where Dixon and Gano, Rutgers’ captains of the enemy’s goal, were waiting, and these two latter sent the ball between the posts amid great applause from the fence top and vicinity.

The first goal had been scored in five minutes of play. During the slight intermission Captain Gummere instructed Michael, a young giant of the Princeton twenty-five, to break up Rutgers’ massing around the ball. Sides were changed and Rutgers “bucked.” In this period the game was more fiercely contested. Time and time again Michael, or “Big Mike,” as he was known, charged into Rutgers’ primitive mass play and scattered the players like a bursted bundle of sticks. On one of these plays Princeton obtained the ball and by a long, accurate kick scored the second goal.

The third goal, or “game,” as it was then called, went to Rutgers. Madison Ball, who had been nonplussing the Princeton men throughout the game by running in the same direction with the ball and upon overtaking it stepping over and kicking the ball behind. him, on one of these plays, by a lucky kick, delivered the ball to Dixon, who was standing directly in front of Princeton’s goal, and in an instant the ball was through and Rutgers once more was in the lead.

The fourth goal was kicked by Princeton, “Big Mike” again bursting up a mass out of which Gummere gained possession of the ball, and with Princeton massed about him easily dribbled the ball down and through the Rutgers goal posts, making the score once more a tie.

The fifth goal was kicked by Gano for Rutgers. The sixth goal also went to Rutgers, but the feature of this period of play in the memory of the players after the lapse of 40 years is awarded to “Big Mike.” Someone by a random kick had driven the ball to one side, where it rolled against the fence and stopped. Large, of Rutgers, led the pursuit for the ball, closely followed by Michael. Just as today a play near the side lines sends an unusual thrill among the spectators, so in this ancient game the crowd of students near the ball started to rise to their feet, but at this instant Large and Michael reached the ball and, unable to check their momentum, in a tremendous impact struck the fence, which gave way with a crash and over went its load of yelling students to the ground.

Every college probably has the humorous tradition of some player who, becoming confused in the excitement of play, has scored against his own team. This tradition at Rutgers almost dated from this first game, for one of her players in the sixth period started to kick the ball through his own goal posts. The kick was blocked, but Princeton took advantage of the opportunity and soon made the goal. This turn of the game apparently disorganized Rutgers, for Princeton also scored the next goal after a few minutes of play, thus bringing the total up to four all.

As custom both at Princeton and Rutgers made a total score of six goals the winning mark, both spectators and players were now aroused to great excitement as the close of the match drew near. At this stage Rutgers resorted to that use of craft which has never failed in the history of 40 years to turn the tide of every close battle. Captain Leggett, of Rutgers, had noticed that Princeton obtained a great advantage from the taller stature of their men, which enabled them to reach above the others and bat the ball in the air in some advantageous direction. This was particularly true of Princeton’s leader, Captain Gummere. On resumption of play Rutgers was ordered to keep the ball clnse to the ground. Following this stratagem, and stimulated by the encouraging shouts of their supporters, the Rutgers men determinedly kicked the ninth and tenth goals, thus winning the match by six goals to four, and with it the historic distinction of a victory in the first game of intercollegiate football played in America.

The memorable day closed with a supper in which both teams participated together, interspersing songs and speeches with the deliciously roasted game birds from the Jersey marshes and meadows.

The second game of the series was played at Princeton the following Saturday, November 13, 1869, the arena being a field across the street from the famous Slidell mansion, later the home of Grover Cleveland. This second contest, however, was played according to Princeton’s custom of free kicks from catch on fly or bound. As Princeton had evolved a high form of strategy in kicking the ball from one to another of their side at close distances, thus creating a series of fair catches and free kicks, Rutgers was wholly outclassed and defeated by eight goals to none.

The third game, owing to the objection of the faculties at Princeton and Rutgers on account of the great and distracting interest aroused, was never played.

A version of this story later appeared in Davis’ 1911 book, Football: The American Intercollegiate Game.

No responses yet