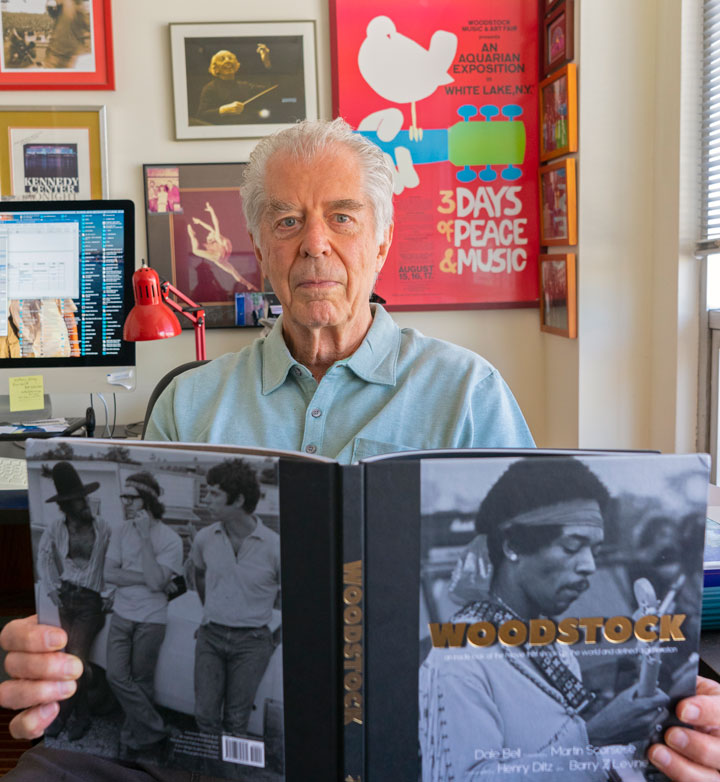

Dale Bell ’60: Living Woodstock

Filmmaker recalls his role in iconic music festival — and how it still resonates half a century later

The filmmaker was there to shoot and help produce what became the Academy Award-winning 1970 documentary Woodstock, a monumental, three-hour-plus ode to the music, people, events, sentiments, and spirit of the tumultuous 1960s. The film’s editors included Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker.

“We were anthropologists in addition to being lovers of music,” says Bell, who has had a long career in television and film. “We designated ourselves the storytellers of the 1960s.”

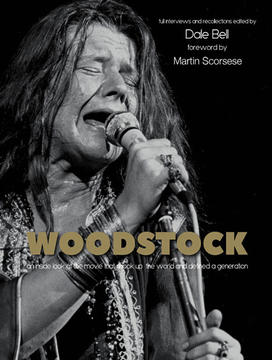

This fall, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the music festival — whose organizers included Joel Rosenman ’63 — Bell will release his third book, Woodstock: Interviews and Recollections (Rare Bird Books), featuring essays by dozens of musicians and moviemakers. “It represents the Rashomon view of us as filmmakers: how we got there, what we did, how it informed the 1960s, how it informed filmmaking, and how we were a merry band of pranksters who assumed the ultimate responsibility of telling one of the ultimate stories of the 1960s.”

Bell has wanted to be a documentary filmmaker ever since he saw Kon-Tiki, the 1950 documentary that chronicled Norwegian explorer and filmmaker Thor Heyerdahl’s raft expedition from South America to Polynesia. “I wanted to be that person I saw on the screen,” says Bell, noting that he learned multiple languages to emulate the multilingual Heyerdahl. He even booked passage as a mess boy on a Norwegian freighter in the summer of 1957 “so I could get to Oslo to meet [him],” Bell says. He never made it to Oslo, but Bell would work with Heyerdahl on the National Geographic special The Tigris Expedition: In Search of Our Beginnings.“I wanted to use the camera as a tool for telling stories about issues that related to social justice,” Bell says. “[At Princeton], I was a loner. I was an explorer. I wanted to learn what other people, besides those at Princeton, were about. It is why I set out in my summers of 1955, 1956, and 1957 as a hitchhiking hobo, an itinerant worker.”

This drive is what motivated Bell to make Woodstock. Along with his friends and colleagues, he’d been involved in the civil-rights movement, the protests against the Vietnam War, and the women’s movement.

“There was this incredible sense of social injustice that was permeating every one of our cores,” he says. “It was this sense of, ‘We are responsible for these young people, this generation. Could we shake up the world with this film?’”

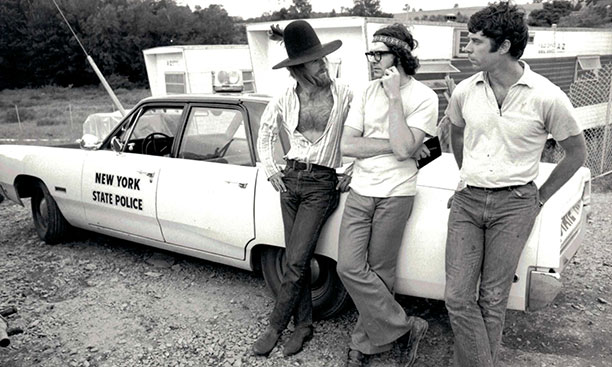

Planning for the film project was minimal, Bell recalls. Until just weeks before the Woodstock Festival, crew members had been planning a concert at Columbia University to test out a new, high-tech editing machine that allowed them to film and splice together three different images — a novelty at the time and well-suited to concert footage. They suddenly realized: Why not just film Woodstock? “We came together in an instant,” Bell says.

With such last-minute preparations, he says, one of the biggest challenges was making sure the team had enough raw film to use; Kodak was shipping it to them one box at a time for the days leading up to and through the concert. Producers were negotiating footage rights with artists on the fly, backstage.

But perhaps the greatest challenge came once all the filming was complete, Bell notes. “Warner Bros. wanted a 90-minute film out for the college crowd in December 1969,” he says. He and his team felt that cutting the footage down to that length and for that purpose would compromise its integrity. The team ended up taking back its sound tracks to ensure Warner Bros. couldn’t re-cut the film, as well as hiring a 24-hour armed guard to protect the negatives.

But Bell and his team were right. Not only did Woodstock win the Academy Award for best documentary, but it continues to resonate with audiences, just like the festival itself.

“It’s a metaphor about life — endurance, sticking together, camaraderie, looking out for each other, helping to feed each other, trusting each other, respecting each other,” Bell says. “Was this film the Magna Carta of the 1960s? Humbly, I vote yes. I didn’t know that we could do that, and I didn’t know that it could last. But it does. We need it now, politically. We need it now.”

A version of this story appears in the Sept. 11, 2019, issue.

1 Response

Adam Reeve

3 Years AgoThanks, Dale Bell

Bravo to Dale and his Woodstock movie-making book! I just finished reading, every page. It really brought me back to the late 1960s. I will be 60 this coming October.