David Remnick ’81 and Jelani Cobb Compile Groundbreaking Writing on Race in America

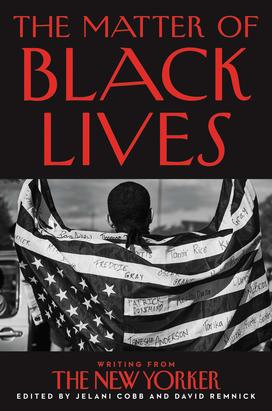

The book: The Matter of Black Lives (Ecco Press), edited by David Remnick ’81 and Jelani Cobb, is a collection of groundbreaking writing on race in America, all previously published in the pages of The New Yorker. Exploring national histories from mid-century America through the modern day, the anthology features writings from James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Hilton Als, Zadie Smith, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and many more celebrated writers and thinkers. Through stories of triumph and tragedy, politics and art, The Matter of Black Lives provides a bold and complex portrait of Black life in America, challenging readers to envision a future guided by new insights on our country’s relationship with race.

The authors: David Remnick ’81 is the editor of The New Yorker, a role he has held since 1998. A Pulitzer Prize winner, he is also the author of several books, including Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero, and The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama. Remnick earned a bachelor’s degree in comparative literature from Princeton, where he also helped found the Nassau Weekly.

Jelani Cobb is a historian and professor of journalism at Columbia University. He has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 2015 and received the 2015 Sidney Hillman Prize for Opinion and Analysis for his columns on race, police, and injustice. Cobb holds a B.A. from Howard University, a master’s degree from Rutgers University, and a Ph.D. from Rutgers.

Excerpt:

FOREWORD

JELANI COBB

In 1962, subscribers to The New Yorker leafed through the pages of the new November 17th issue and, amid the cartoons and the bountiful holiday-season ads, they came upon a long, blistering piece of writing by James Baldwin, “Letter from a Region in My Mind.” The tone, and also the subject, of Baldwin’s prose was unusual, even shocking, for the magazine. As Ben Yagoda writes in “About Town,” a history of the magazine, The New Yorker had, in its early decades, largely kept the subject of race at a distinct remove from its readers. (In doing this, it was similar to most other “mainstream” publications.) There were exceptions, including Rebecca West’s masterly 1947 account of a lynching trial in South Carolina; Comment pieces by E. B. White gently criticizing discrimination; profiles by Joseph Mitchell, Whitney Balliett, and Bernard Taper; and short fiction by Nadine Gordimer. But, as Yagoda writes, between The New Yorker’s founding, in 1925, and the beginning of the Second World War, even the cartoons and the advertisements all too often depicted Black Americans in the most stereotypical terms: “as servants, Pullman porters, and comic figures.”

Baldwin’s essay was, for many readers, a jolt, a concussive experience. It gave no comfort to what Baldwin called the “incredible, abysmal, and really cowardly obtuseness of white liberals.” As an indictment of American bigotry and hypocrisy, tackling themes of violence, sex, history, and religion, the piece continues to resonate more than half a century later. The New Yorker had long employed the rubric “Letter from . . .”—Letter from London, Letter from Johannesburg—as a way to announce the far-flung locations of its correspondents. Baldwin’s title indicated that he was writing, most of all, from his inner depths. (When he published the essay as a book, the following year, he called it “The Fire Next Time.”)

“Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which appeared before the March on Washington and the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, helped to reorient the American discussion of race. The piece also helped to push the magazine, which reached a well-educated, if monochromatic, readership, toward deeper thinking and reporting about an essential American subject. And yet its appearance in the magazine was a matter of publishing happenstance. Like many freelance writers and artists, Baldwin habitually juggled multiple assignments and commitments. He had promised William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, a long report on his travels to the post-colonial states of Senegal, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and Ghana. At the same time, he was working on a piece about his youth in Harlem for Norman Podhoretz, the editor of Commentary. (The multitasking did not stop there; Baldwin was also trying to finish his third novel, “Another Country.”)

Somehow, the African trip, while important to Baldwin as a matter of personal experience, did not inspire successful writing. As his biographer David Leeming ’58 notes, Baldwin formed some tentative impressions of situations and of people whom he met there, but nothing seemed to cohere on the page. He was particularly reluctant to make any presumptions of kinship or shared experiences between Africans and Black Americans. The trip had the paradoxical effect of renewing Baldwin’s interest in the autobiographical essay about Harlem and, by extension, Black life in America. He was also interested in finding a way to make sense of an encounter he’d had with Elijah Muhammad, the diminutive and enigmatic leader of the Chicago-based Nation of Islam. Baldwin wanted to write about the contrast between the Christian Church in which he was raised—his father was a preacher in Harlem—and the Nation of Islam, all in the greater context of the intolerably desperate conditions of Black life in the United States. And so, after giving up on the Africa piece, he concentrated on his American essay. But, instead of sending his manuscript to Podhoretz, he gave it to Shawn, at The New Yorker, which had a much bigger audience than Commentary and paid better. Podhoretz, who later became a godfather of the neoconservative movement, never forgave Baldwin, Shawn, or The New Yorker. (In 1963, Podhoretz published an essay of his own, called “My Negro Problem—and Ours,” but that is another story.)

After publishing the Baldwin essay and sensing its resonance among readers, The New Yorker, like other publications, extended its coverage of race and devoted considerable space to the civil-rights movement. Shawn hired a young woman named Charlayne Hunter (now Hunter-Gault), an aspiring journalist who had generated national headlines when she and her classmate Hamilton Holmes integrated the University of Georgia. At first, she was an editorial assistant. In 1964, after she wrote about a riot in Bedford-Stuyvesant, she was promoted to staff writer, the first Black staff writer in The New Yorker’s history. Calvin Trillin, who came to the magazine from Time, in 1963, and wrote about the drama in Georgia, began reporting consistently on the movement. Renata Adler wrote a long piece on the march from Selma to Montgomery. And, in 1968, Jervis Anderson, a Jamaican-born newspaper reporter, joined the staff and wrote numerous Talk of the Town pieces in addition to profiles of A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Ralph Ellison. His four-part portrait of Harlem in the first half of the twentieth century was eventually published as a book, “This Was Harlem.” The New Yorker had hardly been transformed into Ebony, but it was no longer quite so pale.

The first piece I wrote when I arrived at The New Yorker, in 2012, was titled “Trayvon Martin and the Parameters of Hope,” an exploration of the dynamics surrounding the shooting death of an unarmed seventeen-year-old Black boy in Sanford, Florida, in the context of the Obama Presidency. Martin’s death, and the 2014 police shooting death of eighteen-year-old Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Missouri, launched what has come to be known as the Black Lives Matter movement.

In May, 2020, during the uprising that followed the murder of George Floyd, in Minneapolis, I found myself rereading Baldwin’s essay. I don’t think I was alone. His exploration of race seemed to me as vital, as ragingly alive, as when it was first published, more than half a century ago. And it helped make sense of what we were experiencing: the chaotic, angry, defiant tableaux in the streets of Minneapolis, Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Oakland, Atlanta, Chicago, Houston, Louisville, San Francisco, Indianapolis, Charleston, Detroit, Baltimore, and beyond represented a reckoning, a kind of American Spring, one long in the making. After his death, George Floyd’s name had become a metaphor for the stacked inequities of the society that produced them. Race, to the degree that it represents anything coherent in the United States, is shorthand for a specific set of life probabilities. The inequalities between Black and white Americans are documented in radically varying rates of morbidity and infant mortality, and in wealth and employment. These disparities make it plain that, while race may be a biological fiction, its realities are painfully evident in what is likely to happen in our lives. The more than forty million people of African descent who live in the United States recognize this reality, but it has long been invisible, or of minimal concern, to most white Americans.

This seemed to be part of what Baldwin tried to reckon with in his “Letter.” He wanted to make plain and inescapable that the legacy of racism—of slavery, Jim Crow, and the myriad structures of inequality that shape our lives today—defines, in large measure, the crisis of American life and the question of our common fate. He was arguing for the centrality of the situation. One particularly searing, albeit gendered, line from Baldwin’s “Letter” conveys the sentiment and even the national prospect with precision: the Negro, he wrote, is “the key figure in his country, and the American future is precisely as bright or as dark as his.”

One of the earnest outgrowths of the spring and summer demonstrations of 2020 was the compiling of reading lists—endless lists, from slave narratives to novels to treatises on “white fragility,” distributed by libraries, schools, even corporations. Better to have these lists than not, one supposed; it was a good thing to see at least some of these books get a wider audience, and Kelefa Sanneh wrote about some of them in a critical essay republished here. At The New Yorker, as at other publications, we thought hard about how to write about what the country was experiencing, what and whom we should publish in the future.

At the same time, we began to comb the archives to get a sense of how the political, cultural, and economic questions surrounding race and Black achievement have been portrayed in The New Yorker by writers as distinguished and as various as Toni Morrison and Hilton Als; Zadie Smith and Jamaica Kincaid; Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Elizabeth Alexander—to name just a few. The result is this anthology.

Our hope is that we have assembled a collection, beginning with Baldwin’s “Letter,” that begins to suggest, through an array of writers, the depths of political thinking and argument connected to race in America; the range of cultural accomplishment; the variousness of personal experience. Race has exerted a profound, distorting effect on American life—all of it, not simply the portion labelled with the racial modifier “Black.” But the very nature of the problem Baldwin highlighted insures that it is generally associated with only that sliver of the public. This is not an anthology about race. It is a collection about a broad, fascinating set of events and the people who are most commonly tasked with confronting it. The American future is precisely as bright or as dark as our capacity to grapple with this enduring concern. This collection is a chronicle of at least a part of our past and a lens to help envision a better American future.

Reprinted with permission from The Matter of Black Lives by Jelani Cobb and David Remnick, published by Ecco Press. © 2021 by Ecco Press. All rights reserved.

Reviews:

“More than an antiracist reading list, this collection of mindfully curated historic and contemporary New Yorker texts surveys a wide range of voices and narratives … Cobb and Remnick have assembled a dialogue across generations of New Yorker contributors that encourages readers to engage with the nation’s history of racism and potential for change.” — Library Journal

“Beyond the stellar prose, what unites these pieces, which range widely in length, tone, and point of view, is James Baldwin’s insight, paraphrased by Jelani Cobb, that 'the American future is precisely as bright or as dark as our capacity to grapple with [the legacy of racism].' This standout anthology illuminates a matter of perennial concern." — Publishers Weekly

No responses yet